Read Document

advertisement

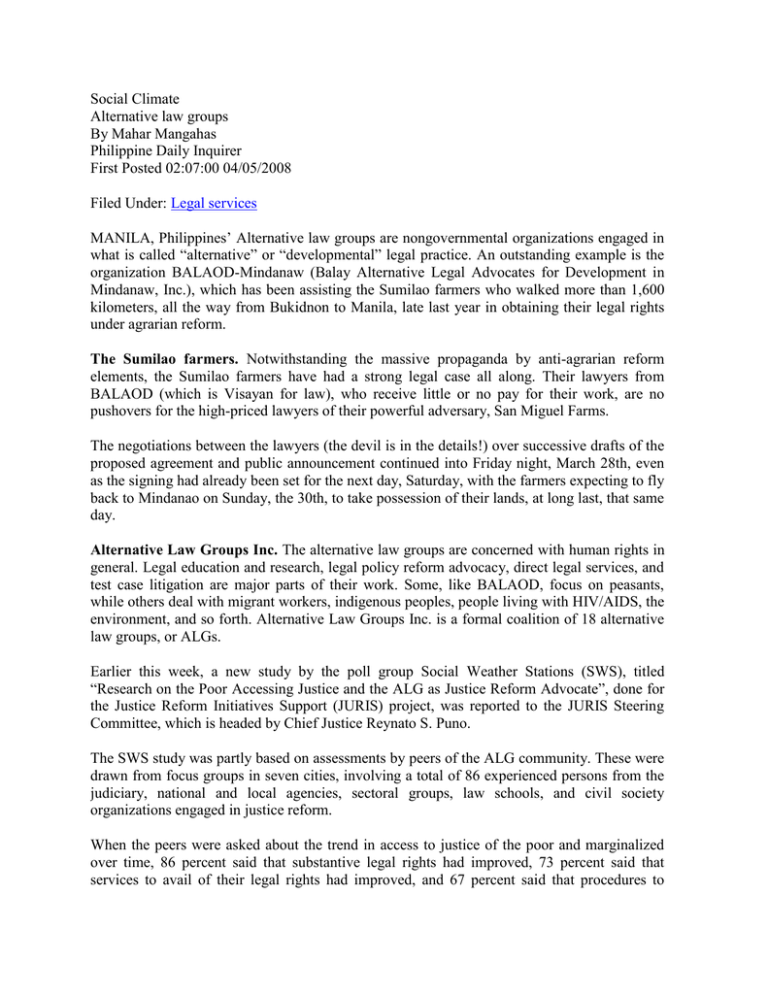

Social Climate Alternative law groups By Mahar Mangahas Philippine Daily Inquirer First Posted 02:07:00 04/05/2008 Filed Under: Legal services MANILA, Philippines’ Alternative law groups are nongovernmental organizations engaged in what is called “alternative” or “developmental” legal practice. An outstanding example is the organization BALAOD-Mindanaw (Balay Alternative Legal Advocates for Development in Mindanaw, Inc.), which has been assisting the Sumilao farmers who walked more than 1,600 kilometers, all the way from Bukidnon to Manila, late last year in obtaining their legal rights under agrarian reform. The Sumilao farmers. Notwithstanding the massive propaganda by anti-agrarian reform elements, the Sumilao farmers have had a strong legal case all along. Their lawyers from BALAOD (which is Visayan for law), who receive little or no pay for their work, are no pushovers for the high-priced lawyers of their powerful adversary, San Miguel Farms. The negotiations between the lawyers (the devil is in the details!) over successive drafts of the proposed agreement and public announcement continued into Friday night, March 28th, even as the signing had already been set for the next day, Saturday, with the farmers expecting to fly back to Mindanao on Sunday, the 30th, to take possession of their lands, at long last, that same day. Alternative Law Groups Inc. The alternative law groups are concerned with human rights in general. Legal education and research, legal policy reform advocacy, direct legal services, and test case litigation are major parts of their work. Some, like BALAOD, focus on peasants, while others deal with migrant workers, indigenous peoples, people living with HIV/AIDS, the environment, and so forth. Alternative Law Groups Inc. is a formal coalition of 18 alternative law groups, or ALGs. Earlier this week, a new study by the poll group Social Weather Stations (SWS), titled “Research on the Poor Accessing Justice and the ALG as Justice Reform Advocate”, done for the Justice Reform Initiatives Support (JURIS) project, was reported to the JURIS Steering Committee, which is headed by Chief Justice Reynato S. Puno. The SWS study was partly based on assessments by peers of the ALG community. These were drawn from focus groups in seven cities, involving a total of 86 experienced persons from the judiciary, national and local agencies, sectoral groups, law schools, and civil society organizations engaged in justice reform. When the peers were asked about the trend in access to justice of the poor and marginalized over time, 86 percent said that substantive legal rights had improved, 73 percent said that services to avail of their legal rights had improved, and 67 percent said that procedures to access justice had improved, compared to five years ago. Some felt that these conditions were unchanged, but very few said they had worsened. In their discussions, the peers attributed the improvement over time to new laws (e.g. the Juvenile Justice Act) and procedures, and to better support services, particularly from the Department of Social Welfare and Development and some local governments. They particularly appreciated the legal services provided by the ALGs and by ALG-trained paralegals. A survey of ALG areas. For the study, SWS also did statistical surveys in seven locations where ALGs operate, with half of the respondents being ALG beneficiaries or “partners”, and half being ordinary individuals from households living in the same locations. In case of an urgent legal problem, about three-fifths of the ALG partners, compared to only two-fifths of the non-partners, felt capable of analyzing the problem, planning action to take, going to the proper court, explaining the law to their families, making affidavits, and gathering evidence, even without the help of a lawyer. On a 32-item battery of True/False questions on knowledge of provisions of law on many sectoral issues, 28 were correctly answered by majorities in ALG target areas. The ALG partners, especially the paralegals and trainees, were more knowledgeable than the nonpartners. Even among the non-partners in the ALG areas, 31 percent knew of NGOs that could provide legal assistance to the poor in their barangays, compared to a national figure of only 15 percent knowing of such NGOs, according to an SWS national survey done for the study at the same time, in September 2007. A national survey on justice for the poor. As of last September, only 38 percent of Filipinos across the country agreed, whereas 45 disagreed, that “Rich or poor, people with cases in court generally receive equal treatment in court”. However, conditions were somewhat better in the ALG areas, where 44 percent agreed, compared to 38 percent who disagreed, with the statement. In both the nation as a whole and ALG areas in particular, survey respondents cited the financial expenses as the main difficulty in fighting for their rights in the hypothetical property dispute case. The focus groups confirmed that problems of competence or attitudes of the courts are only secondary. In other words, although the ALGs make legal services more available to the poor, they cannot by themselves solve the general problem of poverty. *** The SWS study on the access of the poor to justice and on the ALG as justice reform advocate was supported by the Canadian International Development Agency, through the National Judicial Institute of Canada. The full SWS study is published by ALG Inc., Room 215, Institute of Social Order, Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, secretariat@alternativelawgroups.org. Inquiries may be directed to the ALG coordinator, Atty. Marlon J. Manuel, mjmanuel19@yahoo.com. *** Contact SWS: www.sws.org.ph or mahar.mangahas@sws.org.ph. http://opinion.inquirer.net/inquireropinion/columns/view/20080405-128496/Alternative-lawgroup