McCarthyism - Cloudfront.net

advertisement

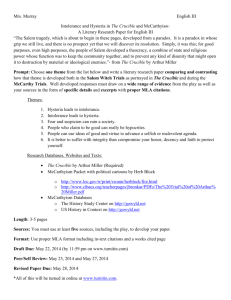

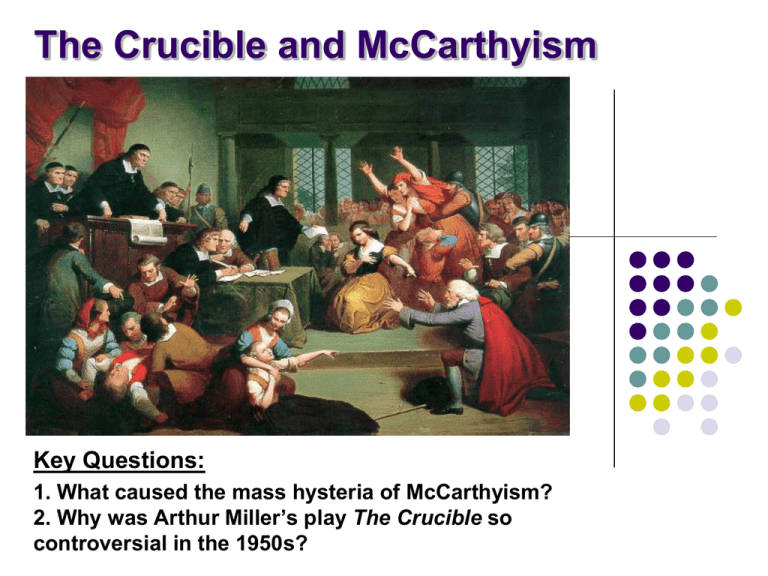

The Crucible and McCarthyism Key Questions: 1. What caused the mass hysteria of McCarthyism? 2. Why was Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible so controversial in the 1950s? Political situation behind the Production of The Crucible McCarthyism and the Anti-Communist Fervor in the 1950s America Deep-seated fear and paranoia of the 1950s After the end of WW II, America became locked in political rivalry with Communist Soviet Union. This is, in a nutshell, was known as the Cold War. The Cold War witness the two superpowers locked in an arms race, which further created an international mood of suspicion and fear. In June 1950, when communist China began to expand into Southeast Asia, America embarked on the Korean War in an attempt to stem the tide of Communism in Asia. American virtue threatened by an insidious enemy? This conflict had an enormous effect on the political climate within the United States. Political, social and business leaders were increasingly concerned that communism threatened the American “way of life.” This so-called Red Scare contributed to widespread paranoia. In this tense era, American federal workers were all required to take loyalty oaths to pledge their allegiance to America, and the U.S. government established loyalty boards to investigate reports of left-wing communist sympathizers. Reign of Terror Unleashed by Senator McCarthy This intense fear that communists were infiltrating America eventually led to the rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy, the most prominent figure in the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) which was established to scrutinize possible communist suspects and uncover their subversive infiltration into American life. McCarthy’s highly controversial investigations were aimed particularly at university teachers, artists, trade unionists, and anyone suspected of left-wing sympathies, which showed his deep-seated fear of the intellectual’s power and influence. Miller called this “the artist-hating brutality”. Fear and Hysteria: A Demand for Ideological Purity HUAC asked the accused to confess, and prove their innocence by naming others. As people began to realize that they might be condemned as Communists regardless of their innocence, many “cooperated,” attempting to save themselves through false confessions, thus creating the image that the United States was overrun with Communists and perpetuating the hysteria. This policy resulted in a whirlwind of accusations. There were many suicides. Those who were revealed, falsely or legitimately, as communists, and those who refused to incriminate their friends, saw their careers suffer, as they were blacklisted from potential jobs for many years afterward. A Closer look at Joseph McCarthy Joseph McCarthy may have been just a senator from Wisconsin, but from about 1950 to 1954, he was one of the most powerful and feared men in the United States. McCarthy played off of a building paranoia of communist infiltration into the United States and exploited people’s fears in order to gain power. Anyone who spoke out against him was labeled a communist and thus was essentially committing career suicide. He even went as far as to rid the libraries of any novels he deemed anti-American. McCarthy manipulated the public’s fear in order to achieve the only thing he cared about: power. McCarthyism and Miller’s The Crucible The liberal entertainment industry, in which Miller worked, was one of the chief targets of these “witch hunts.” Among the accused, some caved in; others, like Miller, refused to give in to questioning. Here is Miller’s response to HUAC’s questioning: “When I say this I want you to understand that I am not protecting the Communists or the Communist Party. I am trying to and will protect my sense of myself. I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him. I take responsibility for everything I have done but I cannot take responsibility for another human being”…. “Nobody wants to be a hero... but in every man there is something he cannot give up and still remain himself - a core, an identity, a thing that is summed up for him by the sound of his own name on his own ears. If he gives that up, he becomes a different man, not himself.” McCarthyism and Miller’s The Crucible However, one of his close friends, Elia Kazan, caved in, and gave Miller’s name to the committee. Miller was fined and given a suspended prison sentence. Extremely depressed about his friend’s inability to stand up to the committee, Miller drove north to Salem, Massachusetts, to begin his research on The Crucible, which would be another community rocked by hysteria, the betrayal of friends under pressure, and one man’s refusal to name names in order to save his own skin. The Salem Witch trials had fascinated him long before he saw their possibility for McCarthyism. But now, the lunacy of McCarthyism and the terror of Salem had merged into one central image, in which the average citizen was willing to accept insanity as a routine. McCarthyism and Miller’s The Crucible It was against this sociopolitical background of fear, anguish, guilt and hysteria that Miller wrote The Crucible, hoping to show the sin of public terror and to capture the wild irrationality of all these events. He admitted that he wrote this play out of desperation, “motivated in some great part by the paralysis that had set in among many liberals who, despite their discomfort with the inquisitors’ violations of civil rights, were fearful, and with good reason, of being identified as covert Communists if they should protest too strongly.” McCarthyism and Miller’s The Crucible “I had known of the Salem witch hunt for many years before ‘McCarthyism’ had arrived and it had always remained in inexplicable darkness to me… “When I looked into it now, however, it was with the contemporary situation at my back, particularly the mystery of the handing over of conscience which seemed to me the central and informing fact of the time… “The central impulse for writing was not the social, but the interior psychological question ... of that guilt residing in Salem which the hysteria merely unleashed, but did not create.” Commenting on McCarthyism, he wrote, “It was not only the rise of ‘McCarthyism’ that moved me, but something which seemed much more weird and mysterious. It was the fact that a political, objective, knowledgeable campaign from the far right was capable of creating not only a terror, but a new subjective reality, a veritable mystique which was gradually assuming even a holy resonance… …The wonder of it all struck me that so practical and picayune a cause, carried forward by such manifestly ridiculous men, should be capable of paralyzing thought itself, and worse, causing to billow up such persuasive clouds of ‘mysterious’ feelings within people. It was as though the whole country had been born anew, without a memory even of certain elemental decencies which a year or two earlier no one would have imagined could be altered, let alone forgotten… “…Astounded, I watched men passed me by without a nod whom I had known rather well for years; and again, the astonishment was produced by my knowledge, which I could not give up, that the terror in these people was been knowingly planned and consciously engineered, and yet that all they knew was terror. That so interior and subjective an emotion could have been so manifestly created from without was a marvel to me. It underlies every word in The Crucible. Arthur Miller, Collected Plays (1957) “If I hadn’t written The Crucible,” Miller said, “that period would have been unregistered in our literature on any popular level…” The Crucible is the work that Miller feels “proudest” because, as he puts it, “I made something lasting out of a violent but brief turmoil.” The Crucible: Then and Now At the time of its first performance on Broadway in January of 1953, critics and cast alike perceived The Crucible as a direct attack on McCarthyism. George Nathan: As a sermon and propaganda it was acceptable; as a drama, it failed. Walter Kerr: Characters in The Crucible were merely mouthpieces for Miller’s politics; they were no more than puppets serving Miller’s own political agenda. In the eyes of the public, the play seemed to confirm Miller’s reputation as a dangerous man. Many reviewers and playgoers believed that viewing and approving this play might taint them as sympathetic to communism. People in those highly charged times had lost their jobs for less. The Crucible: Then and Now Commenting on the hostility of the audience, Miller writes that “as the theme of the play was revealed, an invisible sheet of ice formed over their heads, thick enough to skate on. In the lobby at the end, people with whom I had some fairly close professional acquaintanceships passed me by as though I was invisible.” The play’s popularity did not grow until the Red Scare waned. Today’s audiences, long past the McCarthy paranoia, enjoy the universal themes that the drama embodies. Conclusion The author, Arthur Miller, made a conscious attempt to link the two ideas – the Salem witch trials, 1692, and McCarthyism of the 1950’s. The parallelism of the two historical times makes one aware of the insidious results of the mass hysteria that characterized both time periods. Literature is a form of expression that is sometimes designed to enlighten us of our past mistakes in the hopes that we can learn from them and not repeat them in our future. The fear of the unknown can be a powerful, negative emotion. Let’s hope that it is within our power to control and that such history will not be repeated. Questions… Why was there a fear of communism and communist subversion after World War II? Were these fears justified? Who did McCarthy accuse of having communist sympathies? How were the accused investigated? What happened to them? Why was Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible under such criticism in the 1950s? How did Arthur Miller feel about McCarthyism?