Chapter 9:

Urban Geography

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

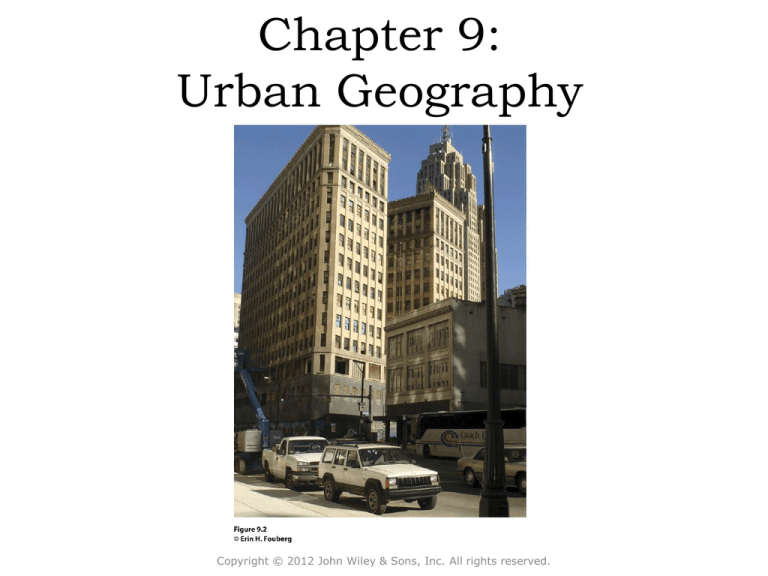

Field Note:

Ghosts of Detroit?

“The semicircular shaped Grand

Circus Park in Detroit, Michigan is

divided by several streets, making

it look like the hub and spokes of a

bicycle wheel from above. The

grouping of buildings along Grand

Circus Park (Fig 9.1) reflects the

rise, fall, and revitalization of the

central business district (CBD) in

Detroit. The central business

district is a concentration of

business and commerce in the

city’s downtown…Abandoned highrise buildings called the ghosts

of Detroit are joined by empty

single-family homes to account for

10,000 abandoned buildings in the

city.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Key Question 9.1

9.1 When and why did people

start living in cities?

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

• urban: the built-up space of the central city

and suburbs

• includes the city and surrounding environs

connected to the city

• is distinctively nonrural and

nonagricultural

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

• A city is an agglomeration of people and

buildings clustered together to serve as a

center of politics, culture, and economics.

Concept caching:

Kansas City, MO

© Barbara Weightman

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Before urbanization, people often clustered

in agricultural villages –

a relatively small, egalitarian village, where most

of the population was involved in agriculture

(mostly subsistence).

about 10,000 years ago, people began living in

agricultural villages

Two components enable the

formation of cities:

1.

an agricultural surplus (irrigation &

large scale farming)

2.

social stratification

(a leadership class that controlled

resources)

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

The Hearths of Urbanization

• The innovation of the city is called the first

urban revolution, and it occurred

independently in six separate hearths, a

case of independent invention.

• The six urban hearths are tied closely to

agriculture.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

In each of these hearths, an agricultural surplus and social stratification created

the conditions necessary for cities to form and be maintained.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

The Hearths of Urbanization

The Six Hearths of Urbanization

1. Mesopotamia, 3500 B.C.E.

2. Nile River Valley, 3200 B.C.E.

3. Indus River Valley, 2200 B.C.E.

4. Huang He Valley, 1500 B.C.E.

5. Mesoamerica, 1100 B.C.E.

6. Peru, 900 B.C.E.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

The Role of the Ancient City in

Society

• served as economic nodes

• were the chief marketplaces

• were the anchors of culture and society,

the focal points of power, authority, and

change

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

Diffusion of Urbanization

• populations in Mesopotamia grew with

the steady food supply and a sedentary

lifestyle

• people migrated out from the hearth,

diffusing their knowledge of agriculture

and urbanization

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

social inequality reflected in varying sizes of

homes

walled villages

palaces

priest-king class

levied taxes & collected tributes from harvest

temples and shrines at centers of towns

built on artificial mounds often over 100 ft high

mud walled homes for regular class

leadership class held slaves

no waste disposal or sanitation

disease was rampant, which kept the population small

link between urbanization and irrigation

power concentrated in the hands of people who

controlled the irrigation systems

no walled cities = singular control

great pyramids, tombs, & sphinx were built

by slaves

Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were

two of the first cities of the Indus

River Valley.

- intricately planned

- houses equal in size

- no palaces

- no monuments

-leadership class but no

variation in houses

-all homes had access to

infrastructure, including

drains & stone lined

wells

-thick walls

-significant trade over

long distances (coins)

The Chinese purposefully

planned their cities.

- centered on a

vertical structure

- inner wall built

around center

- temples and

palaces for the

leadership class

placed inside the inner

wall

-rulers demonstrated

their power by building

elaborate structures,

like the Great Wall of

China

Terracotta Warriors guarding the tomb of the Chinese Emperor Qin Xi Huang

Mayan and Aztec Civilizations

many ancient cities were theocratic centers where rulers were

deemed to have divine authority and were god-kings

Between 300 and

900 CE, Altun Ha,

Belize served as a

thriving trade and

distribution

center for the

Caribbean

merchant canoe

traffic.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

Greek Cities

• Greece is described as a secondary hearth of

urbanization because the Greek city form and

function diffused around the world centuries later

through European colonialism.

• Urbanization diffused from Greece to the Roman

Empire.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Greek Cities

by 500 BCE, Greeks were highly urbanized.

network of more than 500 cities and towns

▪ connected to trade routes diffusion of urbanization

▪ influenced Roman cities

on the mainland and on islands

poor sanitation, compact housing

each city had an acropolis and an agora

▪ acropolis- highpoint of a city where most impressive

structures were built

▪ agora- public space (focus of commercial activity)

the agora

the acropolis

Roman Cities

• When the Romans succeeded the Greeks (and

Etruscans) as rulers of the region, their empire

incorporated not only the Mediterranean shores but

also a large part of interior Europe and North Africa.

• The site of a city is its absolute location, often

chosen for its advantages in trade or defense, or as

a center for religious practice.

• The situation of a city is based on its role in the

larger, surrounding context:

• A city’s situation changes with times.

• Ex.: Rome becoming the center of the Roman

Catholic Church.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Roman Cities

a system of cities and small towns, linked

together with hundreds of miles of roads and

sea routes. (transportation network)

sites of Roman cities were typically for trade

▪ also considered defensibility and religion

a Roman city’s Forum combined the acropolis and agora into one

space. (focal point of public life)

Roman cities had extreme wealth and extreme poverty (between

1/3 and 2/3s of empire’s population was enslaved)

used Greek rectangular grid pattern

most cities had arenas

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

Roman Cities

• urban morphology: a city’s layout; its physical

form and structure.

• Whenever possible, Romans adopted the way the

Greeks planned their colonial cities; in a

rectangular, grid pattern.

• functional zonation reveals how different areas or

segments of a city serve different purposes or

functions within the city.

• Ex.: the forum

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Field Note

“There can be few spaces of greater

significance to the development of

Western civilization than the Roman

Forum. This was the nerve center of a

vast empire that transformed the face

of western Europe, Southwest Asia,

and North Africa. It was also the

place where the decisions were made

that carried forward Greek ideas

about governance, art, urban design,

and technology. The very organization

of space found in the Roman Forum

is still with us: rectilinear street

patterns; distinct buildings for

legislative, executive, and judicial

functions; and public spaces adorned

with statues and fountains.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Urban Growth After Greece and Rome

• During Europe’s Middle Ages, urbanization

continued vigorously outside of Europe.

• In West Africa, trading cities developed along the

southern margin of the Sahara.

• The Americas also experienced significant urban

growth, especially within Mayan and Aztec empires.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Site and Situation during European

Exploration

•

•

•

The relative importance of the interior trade routes

changed when European maritime exploration and

overseas colonization ushered in an era of oceanic,

worldwide trade.

The situation of cities like Paris and Xian changed

from being crucial to an interior trading route to

being left out of oceanic trade.

After European exploration took off during the

1400s, the dominance of interior cities declined.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Site and Situation during European

Exploration

• Coastal cities remained crucial after exploration led

to colonialism.

• The trade networks European powers commanded

(including the slave trade) brought unprecedented

riches to Europe’s burgeoning medieval cities, such

as Amsterdam (the Netherlands), London

(England), Lisbon (Portugal), Liverpool (England),

and Seville (Spain)

• As a result, cities that thrived during mercantilism

took on similar properties.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Field Note

“The contemporary landscape of Genoa stands as a reminder of the city’s historic

importance. Long before Europe became divided up into states, a number of cities in

northern Italy freed themselves from the strictures of feudalism and began to function

autonomously. Genoa and Venice were two of these, and they became the foci of

significant Mediterranean maritime trading empires. In the process, they also became

magnificent, wealthy cities. Although most buildings in Genoa’s urban core date from

a more recent era, the layout of streets and public squares harkens back to the city’s

imperial days. Is it a surprise that the city gave birth to one of the most famous

explorers of all time: Christopher Columbus?”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

A Second Agricultural Revolution

• During the late 17th century and into the

18th century, Europeans invented a series

of important improvements in agriculture.

• The second agricultural revolution also

improved organization of production, market

collaboration, and storage capacities.

• Many industrial cities grew from small

villages or along canal and river routes.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

A Second Urban Revolution

• Around 1800, Western Europe was still

overwhelmingly rural. As thousands

migrated to the cities with industrialization,

cities had to adapt to the mushrooming

population, the proliferation of factories and

supply facilities, the expansion of transport

systems, and the construction of tenements

for the growing labor force.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

When industrialization

diffused from Great

Britain to the European

mainland, the places

most ready for

industrialization had

undergone their own

second agricultural

revolution, had surplus

capital from

mercantilism and

colonialism, and were

located near coal fields.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

When and Why Did People Start

Living in Cities?

The Chaotic Industrial City

• With industrialization, cities became

unregulated jumbles of activity.

• Living conditions were dreadful for workers in

cities, and working conditions were shocking.

• The soot-covered cities of the British Midlands

were deemed the “black towns.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Chaotic

Industrial City

• In mid-1800s, as Karl

Marx and Frederick Engels

encouraged “workers of

the world” to unite,

conditions in European

manufacturing cities

gradually improved.

• During the second half of

the twentieth century, the

nature of manufacturing

changed, as did its

location.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

EVOLUTION OF US URBAN SYSTEM

Five Epochs of Metropolitan Evolution – John Borchert

1.

The Sail-Wagon Epoch (1790-1830): primitive overland and

waterway circulation - leading cities northeastern ports heavily

oriented to European overseas trade - Hinterlands barely accessible.

2.

The Iron Horse Epoch (1830-1870): dominated by steam-powered

railroad, provided nation-wide transportation system, New York

primate city by 1850

3.

The Steel-Rail Epoch (1870-1920): full establishment of national

metropolitan system, increasing scale of manufacturing, rise of steel

and automobile industries, steel rails

Five Epochs of Metropolitan Evolution – (cont.)

4. The Auto-Air-Amenity Epoch (1920-1970): maturation of

national urban hierarchy, key elements were airplane and

automobile, expansion of white-collar services jobs, growing

pull of amenities (pleasant environments) stimulating

urbanization of the suburbs

5. The Satellite-Electronics-Jet Propulsion Epoch (1970- ): newest

advances in information management, computer

technologies,

global communications, and intercontinental

travel; favors

globally-oriented metropolises.

Shenzhen, China

The Modern

Process of

Urbanization –

a rural area can

become

urbanized quite

quickly in the

modern world

Shenzhen, China

Shenzhen changed from a fishing village to a major metropolitan area in just

25 years. 25 years ago, all of this land was duck ponds and rice paddies.

Archaeologists have found that the houses

in Indus River cities, such as Mohenjo-Daro

and Harappa, were a uniform size: each

house had access to a sewer system, and

palaces were absent from the cultural

landscape. Derive a theory as to why these

conditions were present in these cities that

had both a leadership class and a surplus

of agricultural goods.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Key Question 9.2

9.2 Where are cities

located, and why?

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Where Are Cities Located,

and Why?

• Urban geographers discovered that every

city and town has a trade area, an

adjacent region within which its influence

is dominant.

Concept Caching:

Mount Vesuvius arise frequently in

• Three key components

urban geography: population, trade area,

and distance.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rank and Size in the Urban Matrix

• The rank-size rule holds that in a model urban

hierarchy, the population of a city or town will be

inversely proportional to its rank in the hierarchy.

– If the largest city has 12 M people, the second largest will have 6 M (or ½);

the third city will have 4 million (1/3 of 12)

• German Felix Auerbach, linguist George Zipf.

• Random growth (chance) and economies of scale

(efficiency) explain why the rank-size rule works

where it does.

• The rank-size rule does not apply in all countries,

especially countries with one dominant city.

• Mark Jefferson: A primate city is “a country’s

leading city, always disproportionately large and

exceptionally expressive of national capacity and

feeling.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Positive effects of a primate city

within a country

• Lots of economic opportunities

• Large market (pop.) for goods and services

• Ability to offer high-end goods and services

(including education) because of larger threshold

population

• Advantages of centralized transportation and

communication network

• Global trade opportunities; primate cities can

compete on a global scale and attract foreign

investment

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Negative effects of primate city on a

country

• Unequal distribution of investments deters national economic

development

• Unequal economic and/or resource development

• Unequal distribution of wealth and/or power

• Transportation network (hub and spoke) prevents equal accessibility to all

regions

• Impact of centrifugal forces and difficulties of political cohesion on

economic development

• Brain drain – migration and unequal distribution of education,

entrepreneurship, opportunities

• Disproportionate effect of disaster in the primate city on the entire

country

• Negative externalities, e.g., unsustainable urban

growth/slums/environmental impacts if these are related to economic

development, e.g., burden on national economy to cope with problems

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Central Place Theory

Central place theory: Walter Christaller, The Central

Places in Southern Germany (1933), had five

assumptions:

1. The surface of the ideal region would be flat and

have no physical barriers.

2. Soil fertility would be the same everywhere

3. Population and purchasing power would be evenly

distributed.

4. The region would have a uniform transportation

network to permit direct travel from each

settlement to the other.

5. From any given place, a good or service could be

sold in all directions out to a certain distance.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Central Place

Theory

• Each central place has

a surrounding

complementary region,

an exclusive trade area

within which the town

has a monopoly on the

sale of certain goods.

Hexagonal

Hinterlands

• Christaller chose

perfectly fitted hexagonal

regions as the shape of

each trade area.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Central Place Theory

Activity

Central Place

Hexagons

Threshold, Range, Multiplier Effects

http://wn.com/central_place_theory

Christaller looked at the arrangement of urban place

and functions. He started trying to model what he saw.

Ok, pour out your crackers onto your paper towel and

start hypothesizing as Christaller did.

http://myfundi.co.za/e/Settlements_II:_Rural_settlements&usg

Arrangement and Spacing of Urban

Places

• circular shapes resulted in unserved

or overlapped areas

• hexagons had no gaps or overlaps

• this suggests an inverse relationship

of higher order and lower order

settlements (towns and cities)

• theoretically, settlements will be

equidistant from each other

• in other words, big towns/cities are

farther apart from each other

• Why?

Definitions we need to know

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

hamlet, village, town, city, metropolis, megalopolis

population threshold - # of people

market threshold – amount of $ in the place/area

range or range of sale

functional hierarchies

low order goods

high order goods

complementary region- exclusive hinterland within which the

town has a monopoly on the sale of a certain good(s)

rank-size rule

basic sector

non-basic sector

multiplier effect

Assumptions of Central Place Theory

• isotropic plane – no variation (e.g., flat with no barriers to impede

movement

• even population distribution

• rational behavior by consumers – assume that people will minimize the

distance they travel to obtain a good or service

• that is, Consumers visit the nearest central places that provide the

function which they demand

• perfect competition and all sellers are trying to maximize their profits

• consumers have similar purchasing power and demand for goods and

services

• transportation costs are equal in all directions

• no provider of goods or services is able to earn excess profit(each

supplier has a monopoly over a hinterland)

• central places vary in size - small village to a conurbation

• is part of a link in an urban hierarchy

Application of Threshold and Range

using Christaller’s Model

• low order goods have a low range and low threshold

– fewer people needed to support it and thus shorter

distances traveled to obtain it

• Where are low order goods/services?

• higher ranges and higher threshold goods are sold in

larger towns/cities – people will travel longer

distances to obtain these goods/services

• Examples?

• How about a ski resort in DFW?

• Is there the threshold (market or population) for it?

Limitations to CPT

• large areas of flat land are not common

• many forms of transport – costs of each are

not necessarily proportional

• people and wealth not evenly distributed

• purchasing power of people differs

• perfect competition is not realistic – there are

rich and poor

Christaller’s Model Review:

1. Urban places are ranked in an orderly hierarchy.

One is moved? Everything will shift to balance

2. Real world has no absolutes, but Locational

Theory does seem to work

3. Places of same size with same number of

functions would be spaced same distance apart

4. Large cities are spaced farther apart from each

other than towns or villages

So, let’s diagram with the model

Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Table_of_United_S

tates_Metropolitan_Statistical_Areas

Guest Field Note:

Broken Arrow, Oklahoma

“Many trade areas in the United

States are named, and their

names typically coincide with

the vernacular region, the region

people perceive themselves as

living in. In promoting a trade

area, companies often adopt,

name, or shape the name of the

vernacular region. In Oklahoma,

the label Green Country refers

to the northeastern quarter of

the state, the trade area served

by Tulsa.”

Credit: Brad Bays, Oklahoma State

University

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Where Are Cities Located,

and Why?

Central Places Today

• New factors, forces, and conditions not

anticipated by Christaller’s models and

theories make them less relevant today.

• Ex.: The Sun Belt phenomenon: the

movement of millions of Americans from

northern and northeastern states to the

south and southwest.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

• primate cities – a country’s largest city that is

always disproportionately large and

exceptionally expressive of national capacity

and feeling; next largest city is much smaller

and much less influential

• rank-size rule – in a model urban hierarchy,

the population of a city or town will be

inversely proportional to its rank in the

hierarchy. If the largest city

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Key Question 9.3

9.3 How are cities organized,

and how do they function?

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Are Cities Organized, and

How Do They Function?

Models of the City

• functional zonation: the division of the city

into certain regions (zones) for certain

purposes (functions)

• Globalization has created common cultural

landscapes in the financial districts of many

world cities.

• Regional models of cities help us understand

the processes that forged cities in the first

place and understand the impact of modern

linkages and influences now changing cities.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Functional Zones

• A zone is typically preceded by a descriptor that

conveys the purpose of that area of the city.

• Most models define the key economic zone of the

city as the central business district (CBD).

• The central city describes the urban area that is

not suburban. In effect, central city refers to the

older city as opposed to the newer suburbs.

• A suburb is an outlying, functionally uniform part

of an urban area, and is often (but not always)

adjacent to the central city.

• suburbanization is the process by which lands

that were previously outside of the urban

environment become urbanized, as people and

businesses from the city move to these spaces.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Functional Zones

• P.O. Muller: Contemporary Suburban

America (1981):

• Found suburban cities ready to compete

with the central city for leading urban

economic activities.

• In addition to expanding residential zones,

the process of suburbanization rapidly

creates distinct urban regions complete with

industrial, commercial, and educational

components.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Six processes at work in the city

concentration — differential distribution of population

and economic activities in a city, and the manner in

which they have focused on the center of the city

decentralization — the location of activity away from

the central city

segregation — the sorting out of population groups

according to conscious preferences for associating

with one group or another through bias and prejudice

Six processes at work in the city

specialization — similar to segregation only refers to

the economic sector

invasion — traditionally, a process through which a

new activity or social group enters an area

succession — a new use or social group gradually

replaces the former occupants

The following models were constructed to examine

single cities and do not necessarily apply to

metropolitan coalescences so common in today’s

world.

Modeling the North American City

• Concentric zone model: resulted from sociologist

Ernest Burgess’s study of Chicago in the 1920s.

Burgess’s model divides the city into five concentric

zones, defined by their function:

1. CBD is itself subdivided into several subdistricts.

2. Zone of transition is characterized by residential

deterioration and encroachment by business and

light manufacturing.

3. Zone 3 is a ring of closely spaced but adequate

homes occupied by the blue-collar labor force.

4. Zone 4 consists of middle-class residences.

5. Zone 5 is the suburban ring.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Concentric zone model

Developed in 1925 by Ernest W. Burgess

A model with five zones.

Concentric zone model

A model with five zones.

–

Zone 1

the central business district (CBD)

distinct pattern of income levels out to the commuters’

zone

extension of trolley lines had a lot to do with this pattern

Concentric zone model

A model with five zones.

–

Zone 2

characterized by mixed pattern of industrial and

residential land use

rooming houses, small apartments, and tenements

attract the lowest income segment

often includes slums and skid rows, many ethnic ghettos

began here

usually called the transition zone

Concentric zone model

A model with five zones.

– Zone 3

the “workingmen’s quarters”

solid blue-collar, located close to factories of zones 1

and 2

more stable than the transition zone around the CBD

often characterized by ethnic neighborhoods — blocks

of immigrants who broke free from the ghettos

spreading outward because of pressure from transition

zone and because blue-collar workers demanded better

housing

Concentric zone model

A model with five zones.

–

Zone 4

middle class area of “better housing”

established city dwellers, many of whom moved outward

with the first streetcar network

commute to work in the CBD

Concentric zone model

A model with five zones.

–

Zone 5

consists of higher-income families clustered together in

older suburbs

located either on the farthest extension of the trolley or

commuter railroad lines

spacious lots and large houses

from here the rich pressed outward to avoid congestion

and social heterogeneity caused by expansion of zone 4

Concentric zone model

Theory represented the American city in a

new stage of development

–

–

before the 1870s, cities such as New York had

mixed neighborhoods where merchants’ stores

and sweatshop factories were intermingled with

mansions and hovels

rich and poor, immigrant and native-born, rubbed

shoulders in the same neighborhoods

Concentric zone model

In Chicago, Burgess’s home town, the great

fire of 1871 leveled the core

–

–

–

–

the result of rebuilding was a more explicit social

patterning

Chicago became a segregated city with a

concentric pattern

this was the city Burgess used for his model

the actual map of the residential area does not

exactly match his simplified concentric zones

Concentric zone model

critics of the model

–

–

–

pointed out that even though portions of each

zone did exist, rarely were they linked to totally

surround the city

Burgess countered there were distinct barriers,

such as old industrial centers, preventing the

completion of the arc

others felt Burgess, as a sociologist,

overemphasized residential patterns and did not

give proper credit to other land uses

Modeling the North American City

• Homer Hoyt: Sector model

• The city grows outward from the center, so

a low-rent area could extend all the way

from the CBD to the city’s outer edge,

creating zones that are shaped like a piece

of pie.

• The pie-shaped pieces describe the highrent residential, intermediate rent

residential, low-rent residential, education

and recreation, transportation, and

industrial sectors.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Sector model

Homer Hoyt, an economist, presented his

sector model in 1939.

maintained high-rent districts were

instrumental in shaping land-use structure of

the city

because these areas were reinforced by

transportation routes, the pattern of their

development was one of sectors or wedges

Sector model

Hoyt suggested high-rent sector would expand

according to four factors

–

–

–

–

moves from its point of origin near the CBD, along

established routes of travel, toward another nucleus of highrent buildings

will progress toward high ground or along waterfronts, when

these areas are not used for industry

will move along the route of fastest transportation

will move toward open space

Sector model

as high-rent sectors develop, areas between them

are filled in

–

–

–

middle-rent areas move directly next to them, drawing on

their prestige

low-rent areas fill remaining areas

moving away from major routes of travel, rents go from high

to low

there are distinct patterns in today’s cities that echo

Hoyt’s model

he had the advantage of writing later than Burgess

— in the age of the automobile

Sector model

Today, major transportation arteries are

generally freeways.

–

–

–

–

surrounding areas are often low-rent districts

contrary to Hoyt’s theory

freeways were imposed on existing urban pattern

often built through low-rent areas where land was

cheaper and political opposition was less

Multiple nuclei model

suggested by Chauncey Harris and Edward

Ullman in 1945

maintained a city developed with equal

intensity around various points

the CBD was not the sole generator of

change

Multiple nuclei model

equal weight must be given to:

–

–

–

an old community on city outskirts around which

new suburbs clustered

an industrial district that grew from an original

waterfront location

low-income area that began because of some

social stigma attached to site

Multiple nuclei model

more than any other model takes into account the

varied factors of decentralization in the structure of

the North American city

many criticize the concentric zone and sector

theories as being rather deterministic because they

emphasize one single factor

multiple nuclei theory encompasses a larger

spectrum of economic and social possibilities

most urban scholars feel Harris and Ullman

succeeded in trying to integrate the disparate

element of culture into workable model

Multiple nuclei model

rooted their model in four geographic principles

–

certain activities require highly specialized facilities

–

–

–

accessible transportation for a factory

large areas of open land for a housing tract

certain activities cluster because they profit from mutual

association

certain activities repel each other and will not be found in

the same area

certain activities could not make a profit if they paid the high

rent of the most desirable locations

Modeling the North American City

• Chauncy Harris and Edward Ullman:

multiple nuclei model

• This model recognizes that the CBD was

losing its dominant position as the single

nucleus of the urban area.

• Edge cities: Suburban downtowns developed

mainly around big regional shopping centers;

they attracted industrial parks, office

complexes, hotels, restaurants, entertainment facilities, and sports stadiums.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Figure 9.23

Tysons Corner, Virginia. In the suburbs of Washington, D.C., on

Interstate 495 (the Beltway), Tysons Corner has developed as a

major edge city, with offices, retail, and commercial services.

© Rob Crandall/The Image Works.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Modeling the Cities of the Global

Periphery and Semiperiphery

Primate cities in

developing countries are

called megacities when

the city has a large

population, a vast

territorial extent, rapid

in-migration, and a

strained, inadequate

infrastructure.

Concept Caching:

Mumbai, India

© Harm de Blij

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The South American City

• Griffin-Ford model

• South American cities blend traditional

elements of South American culture with

globalization forces that are reshaping the

urban scene, combining radial sectors

and concentric zones.

• The thriving CBD anchors the model.

• Shantytowns are unplanned groups of

crude dwellings and shelters made of

scrap wood, iron, and pieces of cardboard

that develop around cities.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Latin American model

more complex because of influence of local

cultures on urban development

difficult to group cities of the developing

world into one or two comprehensive models

Latin American model is shown in next slide

Latin American model

generalized scheme both sensitive to local cultures

and articulates pervasive influence of international

forces, both Western and non-Western

in contrast to today’s cities in the U.S., the CBDs of

Latin American cities are vibrant, dynamic, and

increasingly specialized

–

–

a reliance on public transit that serves the central city

existence of a large and relatively affluent population

closest to CBD

Latin American model

outside the CBD, the dominant component is a

commercial spine surrounded by

the elite residential sector

–

–

–

–

these two zones are interrelated and called the spine/sector

essentially an extension of the CBD down a major

boulevard

here are the city’s important amenities — parks, theaters,

restaurants, and even golf courses

strict zoning and land controls ensure continuation of these

activities, protecting elite from incursions by low-income

squatters

Latin American model

inner-city zone of maturity

–

–

–

less prestigious collection of traditional colonial

homes and upgraded self-built homes

homes occupied by people unable to participate

in the spine/sector

area of upward mobility

Latin American model

zone of accretion

–

–

–

–

–

diverse collection of housing types, sizes, and

quality

transition between zone of maturity and next zone

area of ongoing construction and change

some neighborhoods have city-provided utilities

other blocks must rely on water and butane

delivery trucks for essential services

Latin American model

zone of peripheral squatter settlements

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

where most recent migrants are found

fringe contrasts with affluent and comfortable suburbs that

ring North American cities

houses often built from scavenged materials

gives the appearance of a refugee camp

surrounded by landscape bare of vegetation that was cut for

fuel and building materials

streets unpaved, open trenches carry wastes, residents

carry water from long distances, electricity is often “pirated”

residents who work have a long commute

many are transformed through time into permanent

neighborhoods

Field Note

“February 1, 2003. A long-held hope came true today: thanks to a

Brazilian intermediary I was allowed to enter and spend a day in two of

Rio de Janeiro’s hillslope favelas, an eight-hour walk through one into

the other. Here live millions of the city’s poor, in areas often ruled by

drug lords and their gangs, with minimal or no public services, amid

squalor and stench, in discomfort and danger.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The African City

• The imprint of European colonialism can still be

seen in many African cities.

• During colonialism, Europeans laid out prominent

urban centers.

• The centers of South Africa’s major cities

(Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban) remain

essentially western.

• Studies of African cities indicate that the central

city often consists of not one but three CBDs: a

remnant of the colonial CBD, an informal and

sometimes periodic market zone, and a transitional

business center where commerce is conducted.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

The Southeast Asian City

Figure 9.27

Model of the Large

Southeast Asian City. A

model of land use in the

medium-sized Southeast

Asian city includes sectors

and zones within each

sector. Adapted with

permission from: T. G.

McGee, The Southeast

Asian City, London: Bell,

1967, p. 128.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Each realm is a separate

economic, social and

political entity that is

linked together to

form a larger metro

framework.

Feminist critiques

models assume only one person is a wage worker —

the male head

ignore dual-income families and households headed

by single women

women contend with a larger array of factors in

making locational decisions

–

–

distances to child care and school facilities

other important services important for different members of

a family

traditional models that assume a spatial separation

of workplace and home are no longer appropriate

Feminist critiques

results of a study of activity patterns of working parents

–

–

–

women living in a city have access to wider array of employment

opportunities

better able to combine domestic and wage labor than women in

suburbs

many middle class women choose a gentrified inner-city location

to live

–

hope this area will offer amenities of suburbs—good schools and

safety

accommodate their activity patterns

other research has shown some businesses locate offices in

suburbs because they rely on labor of highly educated, middle

class women spatially constrained by domestic work

Feminist critiques

most criticisms of above models focus or

their inability to account for all the

complexities of urban forms

all three models assume urban patterns are

shaped by economic trade-offs between:

–

–

desire to live in suburban neighborhood

appropriate to one’s economic status

need to live close to the city center for

employment opportunities

Feminist critiques

most women seek employment closer to home than

men even those without small children

criticism of models by women

–

–

–

–

most families require two real wage earners

models tend to reflect an urban structure that isolates

women who do not participate in the urban labor market

raises problems of timing and organization for those who

combine waged and domestic labor

created by men who shared certain assumptions about how

cities operate, and represent a partial view of urban life

Feminist critiques

other theories incorporated alternative perspective of

female scholars

–

–

studies using mostly female students, focused on “race,”

ethnicity, class, and housing in Chicago

emphasized role of landlords in shaping discrimination in

the housing market

study by urban historian Raymond Mohl

–

–

follows the making of black ghettos in Miami between 1940

and 1960

reveals role of public policy decisions, landlordism, and

discrimination

apartheid and post-apartheid city

apartheid —state-sanctioned policies of

segregating “races”

intended effects of these policies on urban

form are delineated in next slide

apartheid and post-apartheid city

important components of the apartheid state

–

–

policies of economic and political discrimination were

formalized under National Party rule after 1948

government passed two major pieces of legislation in 1950

first was the Population Registration Act — mandated

classification of population into discrete racial groups: white,

black, and colored

second called the Group Areas Act — goal was to divide cities

into sections that could be inhabited only by members of one

population group

apartheid and post-apartheid city

important components of the apartheid state

–

government passed two major pieces of

legislation in 1950

effects of the two acts

–

downtowns were restricted to whites

– areas for non-whites were peripheral, restricted, and often

without urban services—transportation or shopping

– large numbers of non-whites were displaced with little or

no compensation

– buffer zones were created between residential to curtail

contact

apartheid and post-apartheid city

model apartheid city most closely resembles the

sector model

cities were artificially divided into discrete areas

non-white populations suffered the consequences

notorious example — Sophiatown in Johannesburg

remains to be seen what form the post-apartheid city

will take

Soviet and post-Soviet city

cities were shaped by the Bolshevik

revolution of 1917

–

–

socialist principles called for the nationalization of

all resources

economics would no longer dictate land-use—

allocation planners would

new ideals had profound effect on urban

form of Soviet cities

The Soviet and post-Soviet city

Soviet policies attempted to create a more equitable

arrangement of land uses

–

–

–

–

–

relative absence of residential segregation according to

socioeconomic status

equitable housing facilities for most citizens

relatively equal accessibility to sites for distribution of

consumer items

cultural amenities located and priced to be accessible to as

many people as possible

adequate and accessible public transportation

The Soviet and post-Soviet city

The situation outlined above was less than ideal.

–

–

By the 1970s and 1980s many Soviets realized their

standards of living were well below those in the west.

A centralized planning system was not successful.

In the late 1980s economic restructuring introduced

perestroyka.

The post-Soviet city

–

–

market forces are again the dominant force in shaping

urban land uses

pace and scale of urban change are unprecedented

The Soviet and post-Soviet city

privatization of the housing market —example of

Moscow

–

–

–

–

–

private housing grew from 9.3 percent in 1990 to 49.6

percent in 1994

does not mean better housing for all people

many people cannot afford the high prices

apartments are particularly expensive in the center of

Moscow

most people have no choice but to live in communal

apartments from the old Soviet system

The Soviet and post-Soviet city

cities are taking on the look of western cities

–

–

–

–

downtowns now have most expensive land

increasingly dominated by retailing outlets of familiar

Western companies

tall office buildings housing financial activities are replacing

industrial buildings

processes akin to gentrification are taking place in city

centers displacing residents to peripheral portions of the

cities

The outcome of the new changes is not certain and

will be continued to be studied.

Culture Regions

urban culture regions

cultural diffusion in the city

the cultural ecology of the city

cultural integration and models of the city

urban landscapes

Themes in cityscape study

landscape dynamics

–

because North Americans are a restless people,

settlements are cauldrons of change

–

downtown activities creeping into residential areas

deteriorated farmland on city outskirts

older buildings demolished for new

when visual clues are mapped and analyzed, they

offer evidence for current of change

Themes in cityscape study

Equally interesting is to note where change

in not occurring.

–

an unchanging landscape conveys an important

message

part of the city is stagnant because it is removed from

those forces effecting change in other parts

conscious attempt by local residents to inhibit change

preserve open space by resisting suburban

development

preserving a historical landmark

Landscape Dynamics:

Alexandria, Virginia

Landscape Dynamics:

Alexandria, Virginia

Cities grow through

intensification of already

urbanized areas and by

extensification into rural

areas.

This new development is on

agricultural land near

Washington, DC.

Many farmers on urban

peripheries, lured by rising

land prices, ultimately sell to

developers.

Landscape Dynamics:

Alexandria, Virginia

As a mixture of open land

and urban structures, this is

a good example of leapfrog,

or checkerboard

development.

Moreover, the houses are

being sold as “Gentlemen

Farms,” a landscape of the

elite.

Themes in cityscape study

The city as palimpsest

–

–

Because city landscapes change, they offer a field for

uncovering remnants of the past

palimpsest

an old parchment used over and over for written messages

before a new message could be written, the old was erased,

but rarely were all previous characters and words completely

obliterated

the mosaic of old and new is called a palimpsest — used by

geographers to describe visual mixture of old and new in

cultural landscapes

City as palimpsest: Singapore

City as palimpsest: Singapore

Like many cities,

Singapore’s landscape is

one of historic artifacts

amidst the contemporary

fabric. This is the core of old

Singapore, as developed by

the British after 1819.

Strategically situated on the

Straits of Melaka, the city

functioned as an important

entreport in Southeast Asia

attracting a population of

Chinese, Indians, Malays,

and Europeans.

City as Palimpsest: Singapore

Trade offices, shophouses, and

godowns (warehouses) lined

the Singapore river and

commercial activity choked the

area. After Singapore became

independent in 1963-1965, the

combination of rapid population

growth and aging infrastructure

called for a renewal plan. Old

housing stock and godowns

were razed to be replaced by

modern public housing, malls

and office buildings.

City as Palimpsest: Singapore

In the 1980s, people realized

that they were destroying the

character of the city and efforts

were made to preserve and

restore some of old Singapore.

Waterfront shophouses have

been “boutiqued” into clubs and

restaurants. Here, remnants of

the past stand in the shadow of

the symbols fo the future: The

Bank of the People’s Republic

of China (left) and the Telecom

building.

Themes in cityscape study

symbolic cityscapes

–

landscapes contain more than literal messages about

economic functions

–

–

loaded with figurative or metaphorical meaning

subjectivized emotion, memories, and content essential to the

social fabric

to some, skyscrapers are more than high-rise buildings

historic landscapes help people define themselves in time

establish social continuity with the past

codify a forgotten, yet sometimes idealized, past

Themes in cityscape study

D.W. Minig maintains there are three highly

symbolized townscapes in the United States

–

–

–

the New England village

Main Street of Middle America

California Suburbia

each is based upon an actual landscape of a

particular region

each has influenced the shaping of the American

scene over broader areas

Themes in cityscape study

Cultural landscape is important vehicle for constructing and

maintaining social and ethnic distinctions.

–

–

conspicuous consumption is a major means for conveying social

identity

elite landscapes are created through large-lot zoning, imitation

country estates, and detailed ornamental iconography

cultural geographers are interested in how townscapes and

landmarks take on symbolic significance

–

–

–

question whether idealizations are based on some sort of reality or

fabricated from diverse predilections

interested in how to assess the impact of symbolic landscapes

messages inherent in loaded landscapes determine how we treat

our environment-bow it is managed, changed, or protected

Pigeon Problems: Rome, Italy

Pigeon Problems: Rome, Italy

Pigeons, starlings, and

sparrows thrive in urban

environments. Feral

pigeons, descended from

rock doves, favoring cliffface roosts, like to nest in

similar building niches.

Accumulated droppings

raise serious problems.

They corrode stonework,

particularly limestone, and

many historic buildings and

statues have been

irreparably damaged.

Pigeon Problems: Rome, Italy

Fouled pavements are

slippery and hazardous to

pedestrians. Pigeon

excreta, feathers and

detritus can block gutters

and drains providing a

potential health hazard. In

many cities today, people

are discouraged from

feeding pigeons and

renovated buildings are

fitted with spiked rails to

discourage roosting.

Themes in cityscape study

perception of the city

–

–

Social scientists assume if we know what people

see and react to in the city we can design and

create a more humane urban environment.

Kevin Lynch, an urban designer, assumed all

residents have a mental map of the city.

figured out ways people could convey their mental map

to others

What do people react favorably or negatively to?

What do they block out?

Themes in cityscape study

perception of the city

–

On the basis of interviews, Lynch suggested five

important elements in mental maps of cities:

pathways — threads that hold our maps together

edges — tend to define the extremes of our urban vision

nodes — any place where important pathways come

together

districts — small areas with a common identity

landmarks — reference points that stand out because of

shape, height, color, or historic importance.

Themes in cityscape study

Lynch saw some parts of the cities were more legible

than others.

–

–

legibility comes when urban landscape offers clear

pathways, nodes, district, edges, and landmarks

less legible parts of the city do not offer such precise

landscape

Lynch found some cities more legible than others.

–

Jersey City is a city of low legibility

–

wedged between New York City and Newark

fragmented by railroads and highways

residents’ mental maps of Jersey City have large blank

areas

Themes in cityscape study

distinct ethnic, gender, and age variables to

mental maps of cities

–

–

–

often influence everyday behavior

women feel more vulnerable to crime, especially

rape

women will tend to avoid certain areas of a city at

night

The new urban landscape

shopping malls

–

–

–

–

most are not designed to be seen from the outside

retail districts of the 18O0s~and early 1900s cities had

grand architectural displays along the major boulevards

malls are often located near an off ramp of a major freeway

close to middle and upper-class residential neighborhoods

The new urban landscape

shopping malls

–

characteristic form of malls of the 1960s

–

simple, linear form, with department stores at each end

functioning as anchors

usually had 20 to 30 smaller shops connecting the two ends

in the 1970s and 1980s, larger malls had a more complex

form

example: Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota

malls today are often several stories tall and may have 5 or 6 anchor

stores, and up to 400 smaller shops

The new urban landscape

office parks

–

office buildings no longer need to be located in

the center city

–

development of communication technologies

major interstates connect metropolitan areas

cheaper rent in suburban locations

convenience of easy-access parking and privacy of a

separate location

being constructed throughout suburban America

The new urban landscape

office parks

–

–

–

next slide shows location of office parks in

metropolitan Atlanta

many are occupied by regional and national

headquarters of large corporations or local sales

and professional offices

many offices will locate together and rent or buy

space from a land development company to take

advantage of economies of scale

The new urban landscape

office parks

–

the use of the term park points to conscious antiurban imagery

tend to be horizontal in shape — three to six stories tall

many are surrounded by a well-landscaped outdoor

space

human-made lakes and waterfalls, jogging paths, fitness

trails, and picnic tables

The new urban landscape

office parks

–

–

–

do remove workers from social diversity of an

urban location

many office parks are located along what have

been called high-tech corridors — areas along

limited-access highways

this new type of commercial landscape is

gradually replacing downtowns as the workplace

for most Americans

The new urban landscape

master-planned communities

–

many newer residential developments on

suburban fringes are planned and built as

complete neighborhoods by private development

companies

include architecturally compatible housing

have a variety of recreational facilities

exploit various land-use restrictions and zoning

regulations to maintain control over land values

The new urban landscape

master-planned communities

–

example of Weston in south Florida

covers approximately ten thousand acres

land use is completely regulated within gated area and

also along the road system connecting Weston to the

interstate

shrubbery is planted to shield residents from roadway

view

signs are uniform in style

The new urban landscape

festival settings

–

–

–

–

often gentrification efforts focus on a multiuse

redevelopment scheme built around a particular setting,

often one with historical association

waterfronts are commonly chosen as focal points

complexes integrate retailing, office, and entertainment

activities

Knox suggests these developments are “distinctive as new

landscape elements merely because of their scale and their

consequent ability to stage — or merely to be — the

spectacular”

Festival Marketplace: Hong Kong

Festival Marketplace: Hong Kong

Festival settings, both

outdoors and indoors, are

used to attract customers.

There is typically one or

more themes with

flamboyant flags, signs,

music and entertainment.

Retail establishments

include trendy shops,

restaurants, and

entertainment facilities.

Festival Marketplace: Hong Kong

This is one of the

several ultra-modern,

enclosed malls in Hong

Kong. The theme here

is the Dragon Boat

Festival, held annually

in the lunar calendar’s

fifth month. This view

is from an open, tiered

restaurant.

The new urban landscape

festival settings

–

Some festival settings serve as sites for concerts,

ethnic festivals, and street performances.

–

also focal points for more informal human interactions

usually associated with urban life

in this sense do perform a vital function in the attempt to

revitalize downtowns

massive displays of wealth and consumption

often stand in contrast to neighboring areas that

have received little benefit from these projects

The new urban landscape

“militarized” space

–

–

meaning the increasing use of space to set up defenses

against elements of the city considered undesirable

includes landscaping development that range from:

–

–

lack of street furniture to stop homeless living on the streets

gated and guarded residential communities

complete segregation of classes and races’ within the city

As Davis says, “cities of all sizes are rushing to apply and

profit from a formula that links together clustered

development, social homogeneity, and a perception of

security.”

Has taken on epic proportions as many big American cities

become “militarized” spaces.

The new urban landscape

decline of public space

–

–

–

related to the increase in “militarized” space

change in shopping patterns from downtown to shopping

malls

many city governments have joined with developers to built

enclosed walkways above or below city streets

–

provides climate-controlled conditions

provides pedestrians with a “safe” environment to avoid

possible confrontations on the street

some scholars suggest the Internet is a new forum for social

and political interaction

A New Landmark:

London, England

A New Landmark:

London, England

This is the high-tech,

engineering style

(1986) of Lloyd’s of

London Insurance

building. Designed by

Richard Rogers, codesigner of the

Pompidou Center in

Paris, it stands as a

challenge to those in

love with the past.

A New Landmark:

London, England

It stimulates controversy and

has become a landmark

enhancing the legibility of

the city. Not only is it made

of reflective materials and

the glass atrium suspended

on central pillars, but much

of what is traditionally inside,

such as stairways, elevators

and lavatories, is now on the

outside. It is a building with

its guts exposed. The black

structure is Barclay’s Bank.

Urbanization

A country’s leading city, always

disproportionately large and expressive of

nationalistic feelings

Usually center of politics, economics, culture

Rank size rule does not apply to countries with

a primate city

A crescent shaped zone of early urbanization

extending across Eurasia from England to

Japan

Colonialism increased the importance of coastal

cities interior cities became less important

Mercantile city brought about the “downtown” as

we know it today

Nodes of a global network of commerce

Middle class

Became engulfed by desperate immigrants looking for

opportunity

Emergence of a manufacturing city

Unregulated jumbles of activity

Poor sanitation DISEASE

Elegant homes converted to tenement housing as wealthy

& middle class moved out of downtown areas to escape

immigrants

New World cities did not suffer as much as

European cities.

Sub-Saharan Africa least urbanized realm

but fastest growing realm

2nd half of twentieth century manufacturing

cities experience decline

Shift to tertiary services

Transportation advancement has led to the creation

of the modern city suburbs

More dispersed

Rural to urban land use impact?

PO Muller self sufficient entity containing its

own major economic and cultural activities

2000 census 50% of Americans live in the

suburbs

Essence of the modern American city

City where focus has shifted from CBD to

urban fringe

Shopping malls

High tech light manufacturing

White collar firms

Entertainment & hotel complexes

Airports

Located along intersections of major freeways

Urban area is less dispersed

Urban amenities have not relocated to the

suburbs

Do not display sharp contrasts of wealth as

seen in American cities

Multiple family dwellings more common

Many built before modern transportation so streets

are narrow and layout is more compact

More walking and use of metro than cars

Primate cities

Legacy of past is better preserved

Wars have taken their toll

Outlying towns have attracted high tech industries

(outside of greenbelts)

GREENBELTS areas around European cities that

are left to natural state or are preserved gardens,

parks, etc.

Limits urban sprawl

Contains suburbanization

Estimate by the middle of this century, approximately 75% of

ppl will live in urban settings

Hazards of site

Loss of land

Paving less rainfall permeates ground, washes pollutants into water

sources

Pollution

Production of waste (lack of sewer facilities) developing world

Demand for water

NA loses about 1 million acres of farmland every year

China 3 million acres

Changed land cover

No infrastructure

Land not intended for heavy urban use

Urbanization increases water usage by five times per person

Changing consumption habits

More energy, meat (extends pastures & threatens forests)

Immigrants cluster together in an enclave

within a city

All needs met

Invasion and succession neighborhoods remain

the same but new groups come in and out

Redlining

Blockbusting

Racial steering used after blockbusting

became illegal

Realtors encouraged blacks and whites to look for

housing in areas that would promote changing

ghetto boundaries real estate turnover

Modernism v. Postmodernism

Gentrification & commercialization

Inner cities

DINKS & SINKS

Displacement of poor residents who cannot afford

higher real estate

Less tax base

No funding

Govt housing

deglomeration

The Cloverleaf vs The

Access Road and the

AM-PM side of the Market

Two Differing Ideas on Urban and

Economic Development

The Cloverleaf

The Access Road

What are the differences in

development possibilities? Safety?

Aesthetics?

AM vs PM

Key Question

9.4

How do people share cities?

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Zoning laws: Cities define areas of the city and

designate the kinds of development allowed in each

zone.

Figure 9.28

Lomé, Togo. The city’s landscape

reflects a clear dichotomy between the

“haves” and “have-nots.”

© Alexander B. Murphy.

Figure 9.29

Tokyo, Japan. The city’s landscape

reflects the presence of a large middle

class in a densely populated

city. © iStockphoto.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Field Note

“Central Cairo is full of the multistory

buildings, transportation arteries, and

commercial signs that characterize most

contemporary big cities. Outside of a

number of mosques, few remnants of the

old medieval city remain. The first blow

came in the nineteenth century, when a

French educated ruler was determined to

recast Cairo as a world-class city. Inspired

by the planning ideas of Paris’s Baron von

Hausman, he transformed the urban core

into a zone of broad, straight streets. In

more recent years the forces of modern

international capitalism have had the

upper hand. There is little sense of an

overall vision for central Cairo. Instead, it

seems to be a hodge-podge of buildings

and streets devoted to commerce,

administration, and a variety of producer

and consumer services.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Field Note

“Moving out from central Cairo, evidence of

the city’s rapid growth is all around you.

These hastily built housing units are part

of the (often losing) effort to keep up with

the city’s exploding growth. From a city of

just one million people in 1930, Cairo’s

population expanded to six million by

1986. And then high growth rates really

kicked in. Although no one knows the

exact size of the contemporary city, most

estimates suggest that Cairo’s population

has doubled in the last 20 years. This

growth has placed a tremendous strain on

city services. Housing has been a

particularly critical problem—leading to a

landscape

outside

the

urban

core

dominated by hastily built, minimally

functional, and aesthetically non-descript

housing projects.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Shaping Cities in the Global

Periphery and Semiperiphery

• Particularly in the economic periphery, new

arrivals (and long-term residents) crowd together in

overpopulated apartments, dismal tenements, and

teeming slums.

• Cities in poorer parts of the world generally lack

enforceable zoning laws.

• Across the global periphery, the one trait all major

cities display is the stark contrast between the

wealthy and poor.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Shaping Cities in the Global Core

• During the segregation era in the United

States, Realtors, financial lenders, and city

governments defined and segregated spaces

in urban environments.

• Ex.: redlining, blockbusting

• White flight—movement of whites from the

city and adjacent neighborhoods to the

outlying suburbs.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

• In order to counter the suburbanization trend, city

governments are encouraging commercialization

of the central business district and gentrification

of neighborhoods in and around the central

business district.

• Commercialization entails transforming the

central business district into an area attractive to

residents and tourists alike.

• Gentrification is the rehabilitation of houses in

older neighborhoods.

• Teardowns: suburban homes meant for

demolition; the intention is to replace them with

McMansions.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Field Note

“In 2008, downtown Fort Worth, Texas looked

quite different than it did when I first visited in

1997. In that eleven year period, business

leaders in the City of Fort Worth gentrified the

downtown. The Bass family, who has a great deal

of wealth from oil holdings and who now owns

about 40 blocks of downtown Fort Worth, was

instrumental in the city’s gentrification. In the

1970s and 1980s, members of the Bass family

looked at the empty, stark, downtown Fort

Worth, and sought a way to revitalize the

downtown. They worked with the Tandy family to

build and revitalize the spaces of the city, which

took off in the late 1990s and into the present

century. The crown jewel in the gentrified Fort

Worth is the beautiful cultural center called the

Bass Performance Hall, named for Nancy Lee and

Perry R. Bass, which opened in 1998.”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Urban Sprawl and New Urbanism

• Urban sprawl: unrestricted growth of housing,

commercial developments, and roads over large

expanses of land, with little concern for urban

planning

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Urban Sprawl and New Urbanism

• To counter urban sprawl, a group of architects,

urban planners, and developer outlined an urban

design vision they call new urbanism: development,

urban revitalization, and suburban reforms that

create walkable neighborhoods with a diversity of

housing and jobs

• Geographer David Harvey argues the new urbanism

movement is a kind of “spatial determinism” that

does not recognize that “the fundamental difficulty

with modernism was its persistent habit of

privileging spatial forms over social processes.”

• Other critics say “communities” that new urbanists

form through their projects are exclusionary and

deepen the racial segregation of cities.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Field Note

“When I visited Celebration, Florida,

in 1997, I felt like I was walking

onto a movie or television set. The

architecture in the Walt Disney

designed new urbanist development

looked like the quintessential New

England town. Each house has a

porch, but on the day I was there,

the porches sat empty—waiting to

welcome the arrival of their owners

at the end of the work day. We

walked through town, past the 50sstyle movie marquee, and ate lunch

at a 50s-style diner. At that point,

Celebration was still growing.

Across the street from the Bank of

Celebration’ stood a sign marking

the future home of the ‘Church in

Celebration.’”

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Gated Communities

• Fenced-in neighborhoods with controlled access

gates for people and automobiles.

• Main objective is to create a space of safety within

the uncertain urban world.

• Secondary objective is to maintain or increase

housing values in the neighborhood through

enforcement of the neighborhood association’s

bylaws.

• Many fear that the gated communities are a new

form of segregation.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Ethnic Neighborhoods in the

European City

• Ethnic neighborhoods in European cities are

typically affiliated with migrants from former

colonies.

• Migration to Europe is constrained by government

policies and laws.

• European cities are typically more compact,

densely populated, and walkable than American

cities.

• Housing in the European city is often combined

with places of work.

© 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

How Do People Share Cities?

Government Policy and Immigrant

Accommodation

• Whether a public housing zone is divided into

ethnic neighborhoods in a European city depends

in large part on government policy.

• Brussels, Belgium: has very little public housing;

immigrants live in privately owned rentals

throughout the city.

• Amsterdam, the Netherlands: has a great deal of