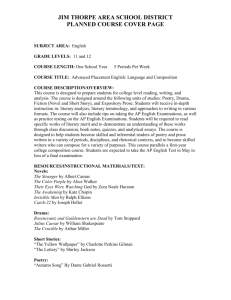

Introduction to Literature

advertisement

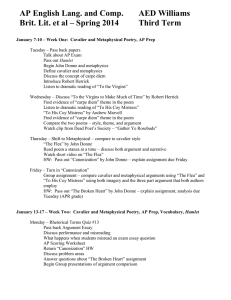

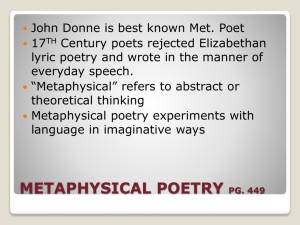

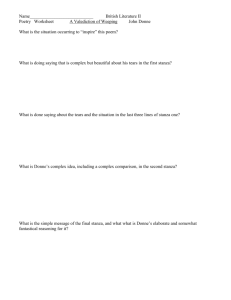

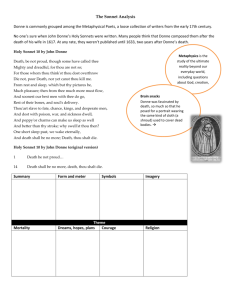

Introduction to Literature Lesson Four: Donne, Suckling, and Behn Love Margarette R. Connor Outline • John Donne – Metaphysical poetry • Discussion of “The Flea” – Carpe diem • Sir John Suckling – Cavalier poets – Discussion of “Out upon it!” • Aphra Behn – Restoration poets – Pastoral – Discussion of “On Her Loving Two Equally” John Donne (1572-1631) • One of the finest poets in England in the early 17th century. • He was a two-sided man. Jack Donne • The adventurous spark, a man about town who writes bawdy and cynical verse to his mistresses. He later writes erotic love poetry to his beloved wife. Dr. Donne • The grave and eloquent divine and dean of St. Paul’s, one of London’s most important churches. One major drawback - his religion • Born into a Roman Catholic family during a peak anti-Roman Catholic time. • Attended both Oxford and Cambridge Universities, but because he was a Roman Catholic, he couldn’t be granted a degree. • Trained as a lawyer at Lincoln’s Inn, where many lawyers were trained in those days, but because he was a Roman Catholic, he couldn’t practice. • Abandoned Roman Catholicism in his 20s, but because he didn’t become an Anglican Catholic, he was still barred from many opportunities. Early Life of Action and Thought • Put his talents to use as a man-about-town, courtier and soldier. • He read enormously in divinity, medicine, law and the classics and he wrote to display his learning and wit. • He had to earn a living as he didn’t inherit enough money to be independent. He traveled the Continent in some of his positions. He saw action as part of the raiding parties to Cádiz and the Azores. • When back in England he played court politics in order to call attention to himself and find preferment. Opportunity knocks • In 1598, when he was 26, he became private secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, one of the highest court officials in England. • In this post he sat in Elizabeth I’s last Parliament and was able to court more power. Elizabeth I Then disaster strikes • In 1601, when he was 29 years old, he secretly married Lady Egerton’s 17-year-old niece, Ann More. • Sir John More, her father, had Donne dismissed from his post and imprisoned for a short while. • While there, he wrote the famous epigraph, “John Donne/Ann Donne/ Undone.” Happy marriage, years of struggle • When he was out of jail, he had a very happy and loving marriage, but he struggled to make a living for his growing family. • He still had friends at court, but his betrayal of the trust of his employer was not forgotten by others. • His refusal to join the Anglican Church didn’t help. Royal Notice • By this time, Queen Elizabeth had died and her successor, James I, had noticed Donne. • Donne had flatly refused to become an Anglican priest in1607, but James was sure he would make an excellent priest. • In 1615, James I pressured him to enter the Anglican Ministry by declaring that Donne could not be employed outside of the Church. • He was appointed Royal Chaplain later that year. James I Preaching in Donne’s time • In those days preaching was something more than just a religious activity. It was – Spiritual devotion – Intellectual exercise – Dramatic entertainment. Donne’s skills • Donne was a great preacher, and in his day he was considered one of the best in England. Factors that made him great: – his metaphorical style, – bold erudition, – dramatic wit. A major change • In 1617, shortly after giving birth to their twelfth child, a stillborn, his wife Ann, aged 33, died. • This event made a difference in Donne and brought out his more pensive, religious side. • Jack Donne was pretty much buried with Ann. The Reverend Doctor Donne • In 1621, he was made Dean of St. Paul’s, as I mentioned, one of the most important churches in London, for this is where many of the most powerful courtiers worshipped. The modern St. Paul’s, rebuilt in the 1670s. Sharp break with his predecessors • He followed the Continental model of more intellectualized conceits – a metaphor or simile that initially appears improbable, but which forces reader to acknowledge the comparison, even though it is exceedingly far-fetched. Metaphysical poets • a term for loose group of 17th century poets – – – – – – Donne Herbert Crashaw Marvell Vaughn Crowley Qualities of metaphysical poetry • Their subject was the relationship of the spirit to matter or the ultimate nature of reality; and • Not merely their subject matter, but the quality of their expression. – Ordinary speech – Love of puns, paradoxes, startling conceits, and obscure, often scientific terminology – Some, including Donne, draw on Renaissance neo-Platonism to show the relationship of soul to the body and the union of lovers’ souls. – Tried to depict a more realistic view of the psychological tensions of sexual love Carpe diem poems • The term is Latin for “seize the day” and poems with this theme advise the listener to enjoy the pleasure of the moment before youth, or life, passes away. • As the famous saying goes, “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die.” The Flea (1) • MARK but this flea, and mark in this, How little that which thou deniest me is ; a man talking to a woman, and he got a flea in his hand. MARK take note of a moral lesson. Donne is making this poem a moral lesson. The Flea (2) • It suck'd me first, and now sucks thee, And in this flea our two bloods mingled be. Thou know'st that this cannot be said A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead ; In the Renaissance, people believed that sexual intercourse actually literally involved the mingling two bodies; making the two become one; and they believe the Blood mingled during the intercourse; this isn’t a sin nor a shame. The Flea (3) • Yet this enjoys before it woo, And pamper'd swells with one blood made of two ; And this, alas ! is more than we would do. this flea is enjoying our two blood mingling while can’t we before we’re married implication in these lines: pamper’d swellspossibilities of woman’s pregnancy The Flea (4) • O stay, three lives in one flea spare, Where we almost, yea, more than married are. This flea is you and I, and this Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is. Though parents grudge, and you, we're met, And cloister'd in these living walls of jet. Though use ( habbit) make you apt to kill me, Let not to that self-murder added be, And sacrilege, three sins in killing three. she’ll be committed three sins is she kills the flea The Flea (5) • Cruel and sudden, hast thou since Purpled thy nail in blood of innocence? Wherein could this flea guilty be, Except in that drop which it suck'd from thee? Yet thou triumph'st, and say'st that thou Find'st not thyself nor me the weaker now. 'Tis true ; then learn how false fears be ; Just so much honour, when thou yield'st to me, Will waste, as this flea's death took life from thee. Sir John Suckling, (1609-1642) • The prototype of the Cavalier playboy. Portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds Who are the Cavaliers? • In 1642, a civil war broke out in England. • There were very complicated reasons for it, but simply put it was Puritans vs Cavaliers. A simple view of the issues • The economic interests of the urban middle class coincided with the religious (Puritan) ideology. Oliver Cromwell, leader of the Parliamentarians • This conflicted with the traditional, agrarian economic interests of the Crown and the allied Anglican Church, which is headed by the King. King Charles I The Opponents • The people who supported the King were called the Cavaliers; the other side were called the Parliamentarians, the Puritans, or disparagingly, the Roundheads (for their bowl-shaped haircuts). Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-71) Captain general of the Parliamentary New Model Army and his opponent Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619-82) nephew of King Charles I and general of Royalist Horse. Center section of the painting depicts cavalry engagement during the battle of Marston Moor. Characteristics of Cavalier poetry • A cultivated but colloquial idiom. They spoke with the ease of a noble (and many of them were). • They employed artificiality, and showed an urbane refinement and elegant symmetry of form instead of feeling. – Form is more important than substance! • They were indebted to the lighter Latin poets - Catullus, Horace and Ovid. • They displayed a strong sensuousness and a worldly quality. They were paganized sophisticates foreshadowing the amorality of the Restoration – this is when the king was restored to power after being exiled for almost 12 years. He went into exile after his father, Charles I, was executed in 1649) Suckling’s early life • Born 1609, son of Sir John Suckling, who had risen to eminence among the court officials of James I – in the last years of his life, was a secretary of state and comptroller of the royal household King James I Education • 1623, entered Trinity college, Cambridge, • 1627, passed to Gray’s Inn, the other place men trained for the law. • The death of his father, in 1627, left him an orphan, and the inheritor of great wealth. • The idea of studying law was now abandoned, and, at 21, Suckling entered upon his adventurous career as a traveller and soldier of fortune. He visited France and Italy, returned to England to be knighted, and, in 1631 fought much in Europe. The Final Years • Between 1632-1639, a courtier, who won him fame and admiration. – plays and poetry, and stayed loyal to his king. • 1639 fighting broke out between English and Scottish. Suckling went to fight for his king. • When civil war threatened, he plotted to have the king control the army. • When the plot was discovered, Suckling fled to France. • Lived anonymously – became more and more dejected. • According to some later writers, he committed suicide in 1642 when the Parliamentarians seemed to be winning the war. Restoration 1660 • England called back Charles II to be their king. • He had been exiled in Holland and his mother’s native France during the time of Puritan rule, and there he had learned to appreciate the freer and more lively style of literature. • When he and his courtiers came back to England, they brought back a taste for more Continental entertainment. “The Incomparable Astrea”: Aphra Behn • Not much is known of her early life. • She was probably born around 1640. • Her early days are shrouded in mystery, and she never did much to uncover it. • Sometime between 1655-1662 she married a Dutch sea captain named Behn. After the Restoration • Behn worked as an undercover spy for the King, trying to convert double-agents. – She went to Holland, then at war with England, and tried to recruit agents from the ranks of the English Puritans who had fled there after the war. • When she returned to England, she was eventually thrown into debtor’s prison for her efforts A prolific writer • In 1670, she brought out her first plays. • In the next twelve years she produced 19 plays. • Wrote 14 narratives, including the first antislavery narrative in English, Oroonoko. • Also produced many volumes of poetry and translations. Ideals of the Cavaliers live on • Behn was loyal to her King and his politics. • She subscribed to the Cavalier beliefs that sexuality was natural and overwhelming, and as such, must be beyond the control of institutions such as religion. • Sexuality must also be free from social constraints like constancy and marriage. The End of her life • Behn died in 1689. • She is buried in Westminster Abbey, though she wasn’t allowed to be buried in Poets’ Corner as she was a woman. Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey. Behn is buried nearby where she can “peer in” at her rivals, as one wit put it. Pastoral poetry • The form goes back to classic Latin and the works of Virgil – revived in the Renaissance What is pastoral poetry? • Shows the desire of humans to conceive of circumstances in which the complexity of human problems are reduced to their simplest elements – shepherds and shepherdesses have no worries, – live in an ideal climate, – their only preoccupations are love and death and making songs and music. Uses of pastoral poetry • It’s used as a vehicle of moral and social criticism – shepherds were innocent of the corrupting luxuries of courts and cities. • It’s also used as a way to allegorically offer thinly disguised tributes of praise and flattery. Illustration to Spenser’s A Shepheard’s Calender