Greek Drama

advertisement

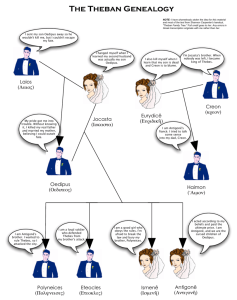

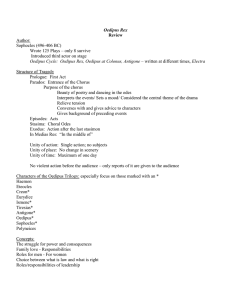

Greek Drama The Origins of Tragedy and Comedy The Greeks drove out their non-Greek neighbors from the Peloponnesian Penisula in the 6th C BC. Afterwards, they had a good deal of time on their hands to consider the big questions of life. Tragedy comes from the Greek roots trag meaning ‘goat’ and odia meaning ‘song’. What do goats have to do with it? A lot, actually. The first plays were devoted to the god Dionysus, the god of wine, merriment and general debauchery. Dionysus’s mythical symbols were the satyrs, lusty men with goats legs who symbolized sexuality and freedom. Our word satire is derived from satyr, and the earliest plays featured actors dressed in goat skins playing these creatures. Aristotle defined Tragedy in his Poetics thusly: “ tragedy is therefore an imitation (that means representation on scene) of a significant and integrated action, which has a certain duration, is characterized by speech with ornament style, the parts of which differ in their form, that is depicted actively (on scene) and is not (just) recited, which causing spectator's sympathy and fear redeems him from similar emotional circumstances.” That is there must be an emotional cleansing for the audience at the end. For this Aristotle coined the term Catharsis. Ancient Greek Idol • The earliest form of drama was called a dithryamb, which was a choral ode sung to Dionysus, usually sung by a group of 20 boys in various costumes. • Different cities would gather to compete in singing competitions which were dedicated to Dionysus. • The judges would decide the winner based on the audience’s reaction. Parts of the Greek Theatre • All plays were performed outside. Early Greek theaters were probably little more than open areas in city centers or next to hillsides where the audience, standing or sitting, could watch and listen to the chorus singing about the exploits of a god or hero. • Orchestra: The orchestra (literally, "dancing space") was normally circular. It was a level space where the chorus would dance, sing, and interact with the actors who were on the stage near the skene. The earliest orchestras were simply made of hard earth, but in the Classical period some orchestras began to be paved with marble and other materials. In the center of the orchestra there was often a thymele, or altar. The orchestra of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was 20 meters in diameter. • Theatron: The theatron (literally, "viewing-place") is where the spectators sat. The theatron was usually part of hillside overlooking the orchestra, and often wrapped around a large portion of the orchestra (see the diagram above). Spectators in the fifth century BC probably sat on cushions or boards, but by the fourth century the theatron of many Greek theaters had marble seats. • Skene: The skene (literally, "tent") was the building directly behind the stage. During the 5th century, the stage of the theater of Dionysus in Athens was probably raised only two or three steps above the level of the orchestra, and was perhaps 25 feet wide and 10 feet deep. The skene was directly in back of the stage, and was usually decorated as a palace, temple, or other building, depending on the needs of the play. It had at least one set of doors, and actors could make entrances and exits through them. There was also access to the roof of the skene from behind, so that actors playing gods and other characters (such as the Watchman at the beginning of Aeschylus' Agamemnon) could appear on the roof, if needed. • Parodos: The parodoi (literally, "passageways") are the paths by which the chorus and some actors (such as those representing messengers or people returning from abroad) made their entrances and exits. The audience also used them to enter and exit the theater before and after the performance. • Eisodos: The Eisodoi were the entrances between the Orchestra and the Parodoi where the main actors made their entrances and exits. The Actors • Only a few actors were used and all played more than one part • No women, female parts were played by young actors who wore wooden breastplates • Masks were worn for many characters; so actors had to change masks off stage when they switched characters • Few props were used, usually only one or two for each play. They would be something important like a hero’s sword or a ceremonial wine challis. • Initially a lot of mime and exaggerated movements were used. The theatres were so large that subtlety was not perceptible to the audience. Later actors relied on their voices (which they trained extensively) and delivered lines in a highly stylized manner. • Most plays were performed in competitions, where prizes were given for the top playwrights, actors and chorus performances. • Elaborate staging was used for the dancers and singers especially. Common Divisions in the Play • Unlike modern Drama, the Greeks did not have Acts to divide their plays. Plays were intended to be shown straight through, with no intermission. • Prologue: A scene which introduces the play and establishes setting and major characters. At least one main character usually appeared. • Parados: (CF “parade”) The first entrance of the Chorus who would enter singing the ode. • Episode: The meat of the play, sandwiched between the choral Stasimon where all of the action happens. Similar to an Act, but shorter, usually about 150-250 lines. • Stasimon: The choral odes in between the Episodes. The Chorus re-enters and gives commentary on the previous Episode. Usually highly poetic and symbolic language. Playwrights often used the Chorus to create Dramatic Irony by revealing information to the audience that the characters are not aware of. • Exodos: The final section of the play, where the Chorus is usually led off stage. In a tragedy, this is usually the part where the catharsis occurs. Background to Antigone • Written by Sophocles around 441 BC. • Part of the “Three Theban Plays” The others are Oedipus the King, and Oedipus at Colonus • Antigone is chronologically the last of the plays, but was written first. • Established Sophocles as the dominant playwright in Greece over Aeschylus. He was even made an honorary general of the Athenian army based on the popularity of the play. In order to understand the events in Antigone, it is necessary to understand some the plot of the two plays which come before it. Oedipus Rex • Oedipus (literally “swollen foot”) is a mythical character. When he was born, the oracle told his father King Laius of Thebes that his son would kill him and marry his mother. • To avoid this peculiar fate, Laius did the only logical thing and took his baby son out to a windswept mountain and nailed his feet to the ground and left him for dead. • Oedipus is found by a shepherd and raised in the court of King Polybus of Corinth. However he hears of the prophecy through a seer, and leaves Corinth to avoid this fate (he believes the King and Queen are his true parents). • On the road he accidentally meets King Laius and, not recognizing him, kills him. • He then solves the riddle of the Sphinx and is rewarded by Creon (brother of Laius and uncle to Oedipus) with the kingdom of Thebes and the hand of Jocasta (his mother!!) • They have some kids (eww): two sons (Eteocles and Polyneices) and two daughters (Antigone and Ismene) • A plague descends on Thebes, a curse from the gods for all this incest. The famous seer Tiresias tells Oedipus he is the cause, but Oedipus doesn’t understand and instead accuses Creon of plotting with Jocasta to overthrow him. • Eventually the truth is revealed, Jocasta hangs herself, Oedipus puts out his own eyes with needles and is led offstage in the Exodos by Antigone “his beard bedewed with eyeballs”! Oedipus at Colonus • Antigone leads Oedipus to Colonus. The villagers tell them they must leave since this place is sacred to the Furies. Oedipus recognizes this from the prophecy which said that he would die in a place sacred to them. • Oedipus entreats the King of Colonus, Theseus, to allow him to stay, pleading that morally he has committed no crime. The chorus decides to reserve judgement. • Ismene comes and says that Eteocles has seized the throne from his brother Polyneices. Polyneices has gotten support from the Argives and is coming back to battle. Both brothers have heard that victory will be determined by where their father is buried (!?). Creon’s plan is to bury Oedipus outside of Thebes with no burial rites (CF Antigone) so the oracle’s prophecy will have no power. Oedipus curses both sons for their disrespect and says that only his daughters are honorable. • Because Oedipus trespassed on the holy ground, the villagers tell him that he must perform certain rites to appease them. Ismene volunteers to go perform them for him, and departs. Meanwhile, the chorus questions Oedipus once more, desiring to know the details of his incest and parricide. Theseus enters, and in contrast to the prying chorus states, "I know all about you, son of Laius.” He sympathizes with Oedipus, and offers him unconditional aide, causing Oedipus to praise Theseus, and offer him the gift of his burial site, which will ensure victory in a future conflict with Thebes. • Creon, who is the king of Thebes, comes to Oedipus and feigns pity for him and his children, telling him that he should return to Thebes. Oedipus is horrified, and recounts all of the harms Creon has inflicted on him. Creon is angry, and seizes Ismene and Antigone. His men begin to carry them off toward Thebes. The chorus attempts to stop him, and calls for Theseus, who comes from sacrificing to Poseidon to condemn Creon, telling him, "You have come to a city that practices justice, that sanctions nothing without law.“ Creon replies by condemning Oedipus, saying "I knew [your city] would never harbor a father-killer...worse, a creature so corrupt, exposed as the mate, the unholy husband of his own mother." Oedipus, infuriated, declares once more that he is not morally responsible for what he did. Theseus leads Creon away to retake the two girls. The Athenians overpower the Thebans and return both girls to Oedipus. Oedipus moves to kiss Theseus in gratitude, then draws back, acknowledging that he is still polluted. • Polyneices comes to see Oedipus who forgives him. Antigone urges Polyneices not to attack his brother, but he will not be dissuaded and storms off. • After much drama, Oedipus finally dies and everyone has nice things to say about him. Anitgone returns to Thebes, hoping to stop the Polyneices and the “Seven against Thebes” of the Argive army… Antigone • Begins after the battle at Thebes where the Argives have been routed and both Polyneices and Eteocles have been killed. • Creon is now king and decrees that Polyneices is a traitor and should not receive the proper burial rites…