Patient with Neurologic Problems

advertisement

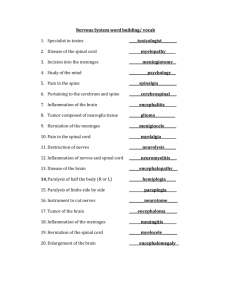

Patient with Neurologic Problems By Linda Self Rapid Neurologic Assessment • Glasgow Coma Scale • Response to painful stimuli—sternal rub, trapezius squeeze • Level of consciousness—even a subtle change is the first indicator of a decline in neurologic status • Decortication—abnormal posturing seen in the client with lesions that interrupt the corticospinal pathways. The patient’s arms, wrists, and fingers are flexed with internal rotation and plantar flexion of the legs. Rapid Neurologic Assessment cont. • Decerebration-abnormal posturing and rigidity characterized by extension of the arms and legs,pronation of the arms, plantar flexion and opisthotonos (kind of spasm with head and feet bent backward and body bowed forward). Indicates dysfunction of the brainstem. Rapid Neurologic Assessment cont. • • 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Pupillary assessment, mental exam Cranial nerve exam Olfactory Optic Oculomotor Trochlear Trigeminal Abducens Facial Acoustic Glossopharyngeal Vagus Spinal accessory hypoglossal Brain Disorders—Migraines Caused by a phenomenon called “cortical spreading depression” whereby neurological activity is depressed over a specific area of the cortex—formerly felt to be related to dilation of cerebral blood vessels Results in release of inflammatory mediators leading to irritation of the nerve roots, especially the trigeminal nerve Serotonin release involved in the causation • Diagnosis is based on H&P, neurologic exam and imaging. Migraines • Triggers 1. Tyramine-containing food and beverages such as beer, wine, aged cheeses, chocolate, yeast, MSG, nitrates, artificial sweeteners, smoked fish 2. Medications:estrogens, nitroglycerine, nifedipine, cimetidine 3. Other: fatigue, hormonal fluctuations, missed meals, sleeping problems, varying altitudes Commonly Used Drugs for Migraines • • • • • • • • NSAIDs Beta blockers such as inderal Calcium channel blockers-verapamil Abortive drugs such as ASA, acetaminophen Ergotamine preparations Triptans Opioids Investigational—droperidol (Inapsine) Seizures • Abnormal, sudden, excessive, uncontrolled electrical discharge of neurons within the brain. May cause change in LOC, motor or sensory ability, and/or behavior. • Epilepsy—chronic disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizure activity Types of Seizures • Generalized 1. Absence—petit mal 2. Tonic-clonic—grand mal. Muscle stiffening followed by jerking 3. Myoclonic—contractions of body muscles 4. Atonic—go “limp”, drop attacks 5. Partial—simple partial, complex partial 6. others Antiepileptic Drugs • Tegretol—partial or generalized seizures • Klonopin—absence, myoclonic and akinetic seizures • Valium—status epilepticus • Depakote—all types • Zarontin-absence seizures • Neurontin—partial seizures • Dilantin-all types • Topamax—for intractable partial seizures • Keppra—adjunct in partial seizures Common side effects of antiepileptics (AEDs) • • • • • • • Teratogenic potential Medication interactions Blood dyscrasias Altered liver function Effects on renal function Wt. gain or loss Sometimes sedation Surgical options • Identify seizure area by EEG, insert electrodes, surgically excise • corpuscallostomy Characteristics of Seizures Important to observe and document: • How often? • Description • Progression • Duration • Last time occurred • Preceded by aura? • What does patient do post-seizure? • Time elapsed before returns to baseline Seizure Precautions • • • • • • • • • • • Stay with patient O2 Airway Suction IV access Siderails up, padded Bed in lowest position Turn patient to side Loosen restrictive clothing Do not force anything into the mouth Following seizure—do neuro checks Status Epilepticus • Characterized by prolonged seizures lasting more than 5 minutes or repeated seizures over the course of 30 minutes • Is a medical emergency. Brain damage and death can ensue. • Untreated can cause hypoxia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, dysrhythmias and lactic acidosis. Rhabdomyolysis can occur with effects on the kidneys. Treatment of Status Epilepticus • Lorazepam is the drug of choice due to rapid onset of action and long duration of action • Valium • Phenobarbital • Dilantin • Supportive/safety care Meningitis • Inflammation of the meninges or brain covering • Entry is via the bloodstream at the blood-brain barrier. May be direct route or via skull fracture. Exudate will develop. • Viral is most common • Fungal-Cryptococcal. Can be caused by sinusitis • Bacterial-mortality rate+25%. Most commonly caused by Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Meningitis—S/S • • • • • • • • • • • LOC Disorientation Photophobia Nystagmus hemiparesis CN dysfunction Personality changes N/V Fever and chills Red macular rash Nuchal rigidity, positive Kernig’s (hamstring pain w/extension) and Brudzinski’s (flexion of the hips when the neck is flexed) Review of CSF findings • Pressure <20cm of H2O • Clear, colorless. Cloudy indicates infection. Pink to orange==RBCs • Cells 0-5 lymphocytes normal. • Glucose—50-75mg/dL normal, less than 50 indicates infection • Proteins 15-45 normal, 45-100 paraventricular tumor, 50-200 viral, more than 500=bacterial infection Meningitis cont. • CSF findings: • Bacterial—cloudy, increased WBCs, increased protein, decreased glucose, elevated CSF pressure >180mm h20 • Viral—clear, increased WBCs, slighly elevated protein, normal glucose, variable CSF pressure Meningitis • May display s/s of increased ICP ( see following slide) • Left untreated, can result in brain herniation or damage Meningitis • Treatment according to causative pathogen as found by LP (lumbar puncture) • Bedrest • IV fluids, analgesics for pain and fever • Anticonvulsants • Corticosteroids • Pathogen specific abx—meningococcus penicillin or cephalosporins, contacts rifampin or cipro; pneumococcal—PCN, cephalosporins and also vancomycin ICP • Pressure-volume relationship between ICP, volume of CSF, blood, brain tissue and cerebral perfusion pressure (Monroe-Kellie Hypothesis) • Cranial compartment is incompressible and cranial contents should have a fixed volume • Equilibrium must be maintained. Increased volume will result in downward displacement of the brain Key Features of Increased Intracranial Pressure • • • • • • • • • • • Lethargy to coma Behavioral changes Headache N/V Change in speech pattern Aphasia Pupillary changes--papilledema Cranial nerve dysfunction Seizures Abnormal posturing Cushing’s Triad—elevated BP, decreased pulse and decreased respirations Treatment of increased ICP • Maintain airway • Hyperventilate patient to “blow off” CO2 (CO2 dilates blood vessels) • Raise HOB to allow for venous drainage • Decrease metabolic demands by paralyzing and sedating patient • Mannitol • corticosteroids • Pain management • Intracranial monitoring (in ventricle) • Craniotomies • Decompressive craniectomy Brain Attacks (Strokes or CVAs) • Affects over 550, 000 Americans per year • Two major types—ischemic and hemorrhagic • Caused by disruption of the normal blood supply to the brain • May be preventable if causes discovered early Risk Factors for Brain Attacks • • • • • • • Obesity Heart disease Diabetes mellitus Hypercholesterolemia Hypercoagulable states Cocaine, illicit drug use Atrial fibrillation Differential Features of the Types of Stroke Thrombotic—onset is gradual • Usually related to ASHD and hypertension • Intact LOC • May have speech and visual changes • Slight HA • No seizures • Deficits may be permanent Differential of strokes Embolic • Abrupt • Steady progression • Awake • May be associated with cardiac disease • Maximal deficits at onset • No seizures • Rapid improvements Differentials of strokes Hemorrhagic • Sudden onset • Deepening stupor or coma • May have hypertension • Focal deficits • Seizures possible • Permanent deficits possible • May result from an aneurysm, rupture of an AV malformation or severe hypertension Ishemic Stroke • Caused by a blockage of a blood vessel • Generally caused by atherosclerosis • Early warning signs include: transient loss of vision, transient ischemic attack (called silent strokes) • Risk factors: atrial fibrillation, ASHD, cocaine use/abuse, hx of “blood clots” • Treatment—”clot buster” TPA, streptokinase,others Transient ischemic attack vs. reversible ischemic neurologic deficit • Ischemic strokes are often preceded by warning signs such as TIAs or RINDs • Both cause transient focal neurologic dysfunction from a brief interruption in cerebral blood flow • TIAs last minutes to <24h • RINDs last >24h but less than a week Hemorrhagic strokes • If survive event, recovery from hemorrhagic stroke better than ischemic • Caused by vascular disruption e.g. aneurysms, AVM • Surgical decompression Assessment of patient with brain attack • Neurologic exam • Motor exam—hemiplegia vs. hemiparesis • Sensory changes-neglect syndrome (most notable in right cerebral hemispheric injuries) • Amaurosis fugax—temporary loss of vision in one eye • Hemianopsia—blindness in one half of visual field • Cranial nerve function • Cardiovascular assessment—abrupt reduction of BP not advised Assessment • Baseline CT, MRI even better (want to ensure that the stroke is not hemorrhagic) • ECG • Echocardiogram • Cardiac enzymes Interventions Depending of type of brain attack: • Anticoagulants (assuming not a bleed) • Catheter directed thrombolytic therapy—may use if systemic tx not effective • Endarterectomy • Craniotomy • Systemic thrombolytic tx—must meet strict criteria. Must give within 3hours of onset of s/s • Wire coils in aneurysms—seals the area Key considerations • Impaired physical mobility; self care deficit • Disturbed sensory perception • Unilateral neglect—in rt cerebral stroke. May have lack of proprioception and failure to recognize their impairment • Impaired verbal communication— expressive aphasia (Broca’s), receptive aphasia (Wernicke’s) Parkinson’s disease • Genetic and environmental contributors • Associated with four cardinal s/s: tremor, rigidity, akinesia (slow movements), and postural instability • Degeneration of substantia nigra— decreased dopamine. Acetylcholine will predominate. Also with norepinephrine loss thus the postural hypotension. Parkinson’s Key Features • Stooped posture • Slow and shuffling gait • Pill-rolling, mask-like facies, uncontrolled drooling, rare arm swinging with walking • Change in voice, dysarthria and echolalia • Labile and depressed, sleep disturbances • Oily skin, excessive perspiration, orthostatic hypotension Parkinson’s Disease Stages • Initial-hand and arm trembling, weakness, unilateral involvement • Mild-masklike facies, shuffling, bilateral involvement • Moderate—increased gait disturbances • Severe—akinesia, rigidity • Complete dependence Interventions • Eldepryl (MAO inhibitor which decreases the breakdown of dopamine) • Dopamine agonists—stimulate dopamine receptors but have side effects such as nausea, drowsiness, postural hypotension and hallucinations. Mirapex and Requip mimic the actions of dopamine. Interventions cont. • Levodopa/carbidopa. Used as disease progresses. “Wearing off” phenomenon. • Amantadine—used to treat the “wearing off” s/s. • Stavelo— (carbidopa/levodopa/entacapone). Dopadecarboxylase inhibitor/dopamine precursor/COMT inhibitor. Useful in endstage disease. Drug toxicity/tolerance in PD 1. Reduce medication dosage 2. Change of medications or in the frequency of administration 3. Drug holiday up to 10 days Nursing considerations • • • • • • • Maintain mobility and flexibility by ROM Encourage self-care as much as possible Monitor sleep patterns to avoid injury Nutrition-may need soft or thickened foods. Constipation Speech therapy may be needed Psychosocial support—impaired memory cognition Surgical Management in PD • Stereotactic pallidotomy • Deep brain stimulation when meds no longer work. Electrode is implanted and connected to a “pacemaker” in chest. • Fetal tissue transplantation using fetal substantia nigra (implanted in the caudate nucleus of the brain). Alzheimer’s Disease • Chronic progressive degenerative disease usually seen in individuals older than 65 • Characterized by loss of memory, judgment, and visuospatial perception and by a change in personality • Progressively physically and cognitively impaired resulting ultimately in death AD • Increased amount of beta amyloid • Neurofibrillary tangles throughout the neurons • Neuritic plaques • Granulovascular degeneration • Reduced levels of acetylcholine • ? Increased levels of glutamate Key Features of AD • Early-forgets names, misplaces household items, mild memory loss, short attention span, subtle changes in personality, wanders, impaired judgment • Middle—cognition vitally impaired; disoriented to time, place and event; agitated; unable to care for self, incontinent • Severe-incapacitated; motor and verbal skills lost Physical Assessment of AD • Observe for stage of progression • Observe for changes in cognition—attention, judgment, learning and memory, communication/language • Observe for changes in behavior • Changes in self-care skills • Psychosocial assessment • Dx of exclusion. Check CMP, CBC, B12, folate, TSH, RPR, drug toxicities and levels, alcohol screening • PET or MRI to r/o pathology • Mini-mental state examination— orientation, registration (repeat three words), naming, reading and following directions. • Good one is to have them draw a clock with an indicated time Interventions for AD • Provide environmental stimulation through contact with people, provide a clock and calendar, present change gradually, allow for rest periods, use repetition • Be concrete • Limit information • Prevent overstimulation and provide structure Interventions cont. • Promote independence in ADL • Be consistent • Promote bowel and bladder contenence fy offering rest room breaks q2h daytime, limit fluids at hs • Administer cholinesterase inhibitors such as Aricept, Reminyl and Exelon. Maintains functionality for a few more months. Interventions cont. • • • • • Provide ID band Monitor to ensure safety from wandering Walk patient to reduce restlessness Involve in activities Restraints only as last resort Multiple Sclerosis (MS) • Also called disseminated sclerosis or encephalomyelitis disseminata • Chronic, inflammatory disease of CNS • Causes gradual destruction of myelin sheath of neurons. Results in scars or sclerosis on the myelin sheaths. • Results from autoimmune process • Between attacks, s/s may resolve but permanent injury occurs as disease progresses MS • • • • Usually affects adults 20-40 years of age More common in women than men Occurs in more temperate climates No cure MS signs and symptoms • Changes in sensation* • Muscle weakness • Incoordination, loss of balance* • Dysarthria • Dysphagia • Visual problems (diplopia)* • Fatigue • Bladder and bowel problems • Cognitive impairment • Heat intolerance *indicates initial or presenting symptoms Diagnosis of MS • MRI • CSF testing will show oligoclonal bands • Visual evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials (sensory and visual nerves respond less actively in MS) • Antibody testing for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and myelin basic protein—in formative stages for testing at this time Types • Relapsing-remitting--charac. by remissions and relapses • Secondary progressive • Primary progressive—no remissions, gradual decline • Progressive relapsing—steady decline with superimposed attacks • ---Copaxone (immunomodulator that targets T-cells, decreases inflammation), Avonex (interferon beta), Betaseron (interferon beta), Tysabri (immunotherapy) • Avoidance of over-heating (Uththoff’s phenomenon) Spinal Cord Injury • Force applied to spinal cord will result in neurologic deficits • Injury may be direct insult to the spinal cord or may be secondary to a contusion, compression or to a concussion (loss of function resulting from a blow) Primary mechanisms of injury • Hyperflexion injury occurs when the head is suddenly and forcefully accelerated forward, causing extreme flexion of the neck. Often occurs in head-on collisions and diving accidents Primary mechanisms of Injury • Hyperextension injuries occur most often in automobile accidents in which the client’s vehicle is struck from behind or during falls when the client’s chin is struck. The head is accelerated and decelerated. Results in stretching or tearing longitudinal ligament, fractures or subluxates vertebrae and may rupture the disc. Primary mechanisms of injury cont. • Axial loading (vertical compression) occurs from diving accidents, falls on the buttocks, or a jump in which a person landed on their feet. The blow may cause the vertebrae to shatter. Pieves of bone enter the spinal canal and damage the cord. Secondary Injury • • • • • Neurogenic shock Vascular insult Hemorrhage Ischemia Fluid and electrolyte imbalance Extent of Injury • Most spinal cord injuries are incomplete lesions • Specific syndrome result from incomplete lesions Cervical Injuries • 1. 2. 3. 4. • May produce: Anterior cord syndrome Posterior cord syndrome Brown-Sequard syndrome Central cord syndrome Cauda equina syndromes are associated with injuries to the lumbar and sacral cord Cervical Injuries • Anterior cord syndrome results from damage to the anterior portion of both gray and white matter of the spinal cord, generally 2ndary to decreased blood supply. Motor function, pain and temperature sensation are lost below the level of injury but touch, position and vibration remain intact. • Posterior cord lesion—rare. Results from damage to the posterior gray and white matter of the spinal cord. Motor function remains intact but the patient loses the sense of position sensation, of crude touch and of vibration. • Brown-Sequard—results from a penetrating injury that causes hemisection of the spinal cord or injuries that affect half of the spinal cord. Motor function, proprioception, vibration and deep touch sensations are lost on the same side of the body as the lesion. On the opposite of the lesion, the sensations of pain, temperature and light touch are affected. • Central cord syndrome—results from a lesion of the central portion of the sc. Loss of motor function is more pronounced in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities. Sensation varies. • Lumbosacral Injuries—damage to the cauda equina or conus medullaris produces a variable pattern of motor or sensory loss as the peripheral nerves have the potential for recovery and regrowth. This injury generally results in a neurogenic bowel and bladder. Vital statistics of spinal cord injuries • Primary cause is trauma secondary to MVA • Unmarried male between 16-30 • Generally are Causcasian • Most injuries are cervical Assessment • Thorough history including mechanism of injury, any changes since initial responder, previous medical history, hx of osteoporosis, osteomyelitis or previous neck or back injuries or surgeries Assessment • First priority for the client with a SCI is assessment of the respiratory pattern and airway • Ensure neck is stabilized • Assess for evidence of abdominal hemorrhage or other sites of injury/hemorrhage • Glasgow Coma Scale • Detailed assessment of the client’s motor and sensory status Spinal Shock • Occurs immediately after injury as a result of disruption of pathways between upper motor neurons (lie in cerebral cortex) and lower motor neurons (lie in spinal cord). • Characterized by: 1. Flaccid paralysis 2. Loss of reflex activity below level of lesion 3. Bradycardia 4. Possible paralytic ileus 5. Hypotension. May last days to weeks; reversal indicated by return of reflex activity Assessment Sensory function • C4-5 can shrug • C5-6 can pull up arms against resistance • C7 can overcome resistance with arms flexed • C8 can grasp objects • L2-4 can raise legs straight up against resistance • L5 apply resistance when patient dorsiflexes • S1apply resistance while the client plantar flexes his feet Cardiovascular • Dysfunction r/t disruption of the autonomic nervous system, especially if above T-6 • Bradycardia, hypotension and hypothermia may result from disruption of sympathetic input • BP < 90 torr requires intervention to ensure satisfactory perfusion of the spinal ccord Respiratory • Can develop from both immobility and from interruption of spinal innervation to the respiratory muscles • C3-5 innervate the diaphragm Gastrointestinal and Genitourinary assessment • Must assess the patient’s abdomen for indications of hemorrhage, distention or paralytic ileus • Ileus may develop within 72h of the injury. Can cause areflexic bladder which can lead to urinary retention and a neurogenic bladder. Musculoskeletal Assessment • Assess muscle tone and size • Muscle wasting is 2ndary to long-term flaccid paralysis seen in lower motor neuron lesions (cell body lies in ant. gray column of spinal cord. Innervates striated muscles). • Upper motor neuron lesions (neuron body lies in cortex, axon synapses with lower motor neuron). Causes spasticity. Interventions for Patients with Spinal Cord Injuries • Immobilization for cervical injuries—fixed skeletal traction such as halo fixation or tongs • Maintain proper alignment of head, neck and body • Turn using the log roll technique • Monitor skin integrity • Traction pin insertion site care • If thoracic or lumbosacral injury—immobilize with corset or brace • Medications—supportive, may use steroids, baclofen, other meds under investigation Interventions for patients with SCIs • Surgical decompression and stabilization—spinal fusion, insertion of Harrington rods, laminectomy (excision of a posterior vertebral arch) • Prevent complications of immobility • Promote self-care • Bladder retraining—spastic (UMN) or flaccid (LMN) may be able to initiate voiding or may need I&O catherterizations Interventions cont. • Bowel retraining—LMN may have to have manual disimpactions, see p. 993. • Rehab, involve community resources • Home care management • Psychosocial implications Autonomic Dysreflexia or Hyperreflexia • Commonly seen in patients with injury to the upper spinal cord (T5 and above). Caused by massive sympathetic discharge of stimuli from the autonomic nervous system. • Stimulus sends nerve impulses to sc, travel upward until blocked by lesion at level of injury. Can’t reach brain so reflex is activated that increases activity of sympaathetic portion of ANS. Autonomic dysreflexia cont. • Increased activity of sympathetic portion of ANS results in spasms and a narrowing of blood vessels with resultant rise in BP. Brain perceives elevated BP, sends message to heart which slows down and dilates vessels above level of injury to dilate. Brain cannot send messages below level of injury so BP cannot be regulated. Autonomic Dysreflexia • Precipitated by distension of the bladder or colon; catheterization of or irrigation of the bladder • Is a medical emergency Key Features of Autonomic Dysreflexia • • • • • • • • • Sudden onset of severe, throbbing headache Severe, rapidly occurring hypertension Bradycardia Flushing above the level of the lesion Pale extremities below the lesion Nausea Blurred vision Piloerection Feeling of apprehension Care of Patient experiencing Autonomic Dysreflexia • • • • • • • Place in sitting position Notify physician Loosen tight clothing Assess for cause Check foley cath If no cath, check bladder for distention Place anesthetic ointment on tip of catheter before insertion Care of Patient with Autonomic Dysreflexia cont. • Check for fecal impaction, disimpact with anesthetic ointment if present • Check room to ensure not too cool • Monitor BP q15 minutes • Give nitrates or hydralazine as ordered Myasthenia Gravis (MG) • Autoimmune disease of neuromuscular junction. Characterized by flare-ups and remissions. Caused by auto antibody attack on the acetylcholine receptors. May be related to hyperplasia of the thymus. • Presents with muscle weakness that improves with rest, poor posture, ocular palsies, ptosis, diplopia, respiratory compromise, bowel and bladder problems MG • Diagnosis based on H&P, labs which include thyroid studies, tests to R/O inflammatory illnesses, (RA, SLE, polymyositis), acetylcholine receptor antibodies (positive confirms but negative does not rule out) MG • Testing with cholinesterase inhibitors (Tensilon). Baseline muscle strength tested then injection given. Within 30-40 seconds, most myasthenic patients show a marked improvement in muscle tone that lasts several minutes. • May be used to distinguish between myasthenic crisis and cholinergic crisis. Myasthenic Crisis • Undermedicated with anticholinesterase drugs. • Increased pulse and respirations • Rise in BP • Anoxia • Cyanosis • Bowel and bladder incontinence • Absence of cough and swallowing reflex Cholinergic crisis • • • • • • • Like being tx with chemical weapons Too much acetylcholine Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea Abdominal cramps Muscle twitching Hypotension Blurred vision Treatment of MG • Immunosuppression with steroids, Imuran or Cytoxan • Plasmapheresis • Resp. support • Nutritional support • Eye protection if unable to close eyes completely • Thymectomy • Maintanance—cholinesterase inhibitor drugs such as Mestinon