Cognitive Psychology - Social Sciences @ Groby

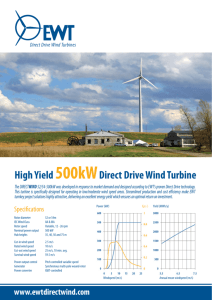

advertisement

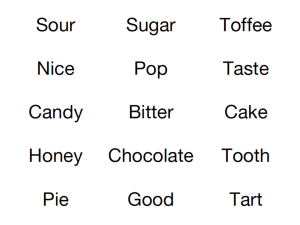

Cognitive Psychology PSYA1 Revision Models of Memory Nature of Memory STM DURATION Peterson and Peterson (1959) Nairne et al (1999) CAPACITY Miller (1956) Simon (1974) ENCODING Baddeley (1966) LTM Bahrick et al (1975) Baddeley (1966) Peterson and Peterson presented their 24 participants with nonsense gaveWRT ppts or lists ofPpts words that were Baddeley gave ppts lists of words thatBaddeley were semantically trigrams followed by three numbers (e.g. 303). were then Bahrick et al asked ppts to put names to the Miller claimed the magic the number is 7±2 (i.e. in STM Nairne et al repeated study by Peterson and Peterson and semantically orhad acoustically dissimilar. acoustically similar dissimilar. He that ppts difficulty askedortoMiller countand backsaid in found 3s from asize chosen number. Thissimilar was to48or prevent faces in their school yearbook, years after Simon criticised that the of the youfound can hold 5-9 ‘chunks’ ofduration information) and that the STM could have a of 96 seconds if the nonsense The ppts did a task for 20 minutes. He found with acoustically similar in STMthe (sononsense STM encodes rehearsal. Theywords then recalled trigram and %70% recallaccurate rates that leaving school. Ppts were chunk does matter that theppts larger the chunk, size of recorded theand chunk doesn’t matter was same across trials.with had difficulty semantically were trigram on athe graph. Results showed duration of STMsimilar to be words acoustically) the less chunks you remember in LTM (so LTM encodes semantically) about 18 seconds. Multi-Store Model Atkinson and Shiffren (1968) AO1 AO2 Strengths Maintenance It is the first model and can then be tested Rehearsal It gives an account of structure and Maintenance Rehearsal process 3 stores and attention & rehearsal Lots of research evidence: Long-term Sensory memory – Sperling (1960) Memory STM & LTM – Serial Position Effect Retrieval Clive Wearing shows that STM and LTM Attention Short-term are separate stores Long-term Retrieval Environmental Stimuli Sensory Attention Memory Environmental Stimuli Short-term Memory Sensory Memory Elaborative Rehearsal Information Retrieval What is the difference between elaborative and maintenance rehearsal? What is the importance of attention? Weaknesses Memory Memory Elaborative Oversimplified ThereRehearsal is too much reliance on rehearsal Focuses too much on structure and too little on process Information KF – brain damage due to car accident Retrieval and had problems with verbal, but normal visual…is there more than one STM? Working Memory Model Baddeley and Hitch AO1 Strengths Central Executive Phonological Loop Visuo-Spatial Sketchpad Episodic Buffer AO2 Lots of research evidence: CE – Bunge et al PL – Baddeley (word-length effect) VSS – Baddeley (dot of light) EB – Baddeley (unrelated words vs. sentences) KF – supports that there is more than one store for STM Does not rely on rehearsal Emphasises process more than MSM Weaknesses The knowledge of the central LTM executive is too vague (what is it?!) Maybe there is more than one CE Difficult to make before and after comparisons with brain damaged patients Memory in Everyday Life EWT The role of misleading information Loftus and Palmer (1974) 45 ppts watched a video of a car crash. They were then asked “About how fast were the cars going when they ______ each other?” The IV was the verb used (smashed, collided, bumped, hit, contacted). The DV was the estimate of speed. Results showed that the leading question influenced memory for the event, with ‘smashed’ giving the highest speed estimates. Problems with EWT studies • Most research into EWT has been conducted in a lab so has low ecological validity. • By watching a video people do not become as emotionally aroused in the way they would for a real life accident. • EW reports can often be inaccurate and contributes to conviction of innocent people • Small, ethnocentric samples have been used. Yuille and Cutshall (1986) EWT in real life 13 people witnessed an armed robbery in Canada. They were interviewed 4 months after the crash and this included 2 misleading questions. Ppts were able to give an accurate recall of the event compared to initial reports. This suggests that post-event information may not effect memory in real-life EWT. Loftus and Palmer (1974) 150 ppts were used to investigate whether post-event information could alter a ppts memory of an event before it was stored. 3 groups watched a video of a car crash. Group 1 was asked “about how fast were the cars going when they smashed”. Group 2 was asked the same question, but “hit”. Group 3 (control group) was asked nothing. The ppts came back a week later and were asked if they saw any broken glass (misleading question). Those who thought the cars were travelling faster were more likely to report seeing broken glass. EWT The role of misleading information Loftus and Palmer (1974) 45 ppts watched a video of a car crash. They were then asked “About how fast were the cars going when they ______ each other?” The IV was the verb used (smashed, collided, bumped, hit, contacted). The DV was the estimate of speed. Results showed that the leading question influenced memory for the event, with ‘smashed’ giving the highest speed estimates. Problems with EWT studies • Most research into EWT has been conducted in a lab so has low ecological validity. • By watching a video people do not become as emotionally aroused in the way they would for a real life accident. • EW reports can often be inaccurate and contributes to conviction of innocent people • Small, ethnocentric samples have been used. Yuille and Cutshall (1986) EWT in real life 13 people witnessed an armed robbery in Canada. They were interviewed 4 months after the crash and this included 2 misleading questions. Ppts were able to give an accurate recall of the event compared to initial reports. This suggests that post-event information may not effect memory in real-life EWT. Loftus and Palmer (1974) 150 ppts were used to investigate whether post-event information could alter a ppts memory of an event before it was stored. 3 groups watched a video of a car crash. Group 1 was asked “about how fast were the cars going when they smashed”. Group 2 was asked the same question, but “hit”. Group 3 (control group) was asked nothing. The ppts came back a week later and were asked if they saw any broken glass (misleading question). Those who thought the cars were travelling faster were more likely to report seeing broken glass. EWT The role of misleading information Loftus and Palmer (1974) 45 ppts watched a video of a car crash. They were then asked “About how fast were the cars going when they ______ each other?” The IV was the verb used (smashed, collided, bumped, hit, contacted). The DV was the estimate of speed. Results showed that the leading question influenced memory for the event, with ‘smashed’ giving the highest speed estimates. Problems with EWT studies • Most research into EWT has been conducted in a lab so has low ecological validity. • By watching a video people do not become as emotionally aroused in the way they would for a real life accident. • EW reports can often be inaccurate and contributes to conviction of innocent people • Small, ethnocentric samples have been used. Yuille and Cutshall (1986) EWT in real life 13 people witnessed an armed robbery in Canada. They were interviewed 4 months after the crash and this included 2 misleading questions. Ppts were able to give an accurate recall of the event compared to initial reports. This suggests that post-event information may not effect memory in real-life EWT. Loftus and Palmer (1974) 150 ppts were used to investigate whether post-event information could alter a ppts memory of an event before it was stored. 3 groups watched a video of a car crash. Group 1 was asked “about how fast were the cars going when they smashed”. Group 2 was asked the same question, but “hit”. Group 3 (control group) was asked nothing. The ppts came back a week later and were asked if they saw any broken glass (misleading question). Those who thought the cars were travelling faster were more likely to report seeing broken glass. EWT The role of misleading information Loftus and Palmer (1974) 45 ppts watched a video of a car crash. They were then asked “About how fast were the cars going when they ______ each other?” The IV was the verb used (smashed, collided, bumped, hit, contacted). The DV was the estimate of speed. Results showed that the leading question influenced memory for the event, with ‘smashed’ giving the highest speed estimates. Problems with EWT studies • Most research into EWT has been conducted in a lab so has low ecological validity. • By watching a video people do not become as emotionally aroused in the way they would for a real life accident. • EW reports can often be inaccurate and contributes to conviction of innocent people • Small, ethnocentric samples have been used. Yuille and Cutshall (1986) EWT in real life 13 people witnessed an armed robbery in Canada. They were interviewed 4 months after the crash and this included 2 misleading questions. Ppts were able to give an accurate recall of the event compared to initial reports. This suggests that post-event information may not effect memory in real-life EWT. Loftus and Palmer (1974) 150 ppts were used to investigate whether post-event information could alter a ppts memory of an event before it was stored. 3 groups watched a video of a car crash. Group 1 was asked “about how fast were the cars going when they smashed”. Group 2 was asked the same question, but “hit”. Group 3 (control group) was asked nothing. The ppts came back a week later and were asked if they saw any broken glass (misleading question). Those who thought the cars were travelling faster were more likely to report seeing broken glass. Factors that influence EWT Age Age differences Evaluation Own-age bias has also been investigated as Yarmey (1993) 651 adults were asked to recall the physical characteristics of a woman that they had spoken to for 15 seconds, 2 minutes earlier. Young (18-29) and middle-aged (30-44) ppts were more confident than older (45-65), and there were significant differences in accuracy of recall (the oldest were inferior). Parker and Carranza Showed 48 schools children and 48 college students a slide sequence of a mock crime. This was followed by a target-present or targetabsent photo identification with a no-choice option, central and peripheral questions related to the crime, and a second photo identification. RESULTS showed that child witnesses were more likely to choose a photo than adult eyewitnesses (so children are more likely to respond). In the questioning task, adults were more likely to say 'I don't know'. Child witnesses were less accurate in line-ups where the 'target' was absent, but there was no differences between age groups when the 'target' was present. part of EWT research. Most research has shown that older adults are poorer on tests of eyewitness memory. But this could be due to the images shown to these adults; often the pictures are of college-aged students, which is easier for students of this age group to identify. Own-age bias Anastasi and Rhodes (2006) 18-25; 35-45; and 55-78 year olds were shown 24 photos of all three age groups. They were asked to rate the photos for attractiveness. There was a short filler task and then ppts were then shown 48 photos. Recognition rates showed that young and middle aged ppts were more accurate than older ppts. But all ages were better at recognising their own age group. The differential experience hypothesis (Brigham and Malpass, 1985) explains own-age and own-race bias. It suggests that as you have more contact with members of these groups our memory is better for these individuals. Factors that influence EWT Anxiety Research There is no simple relationship explaining anxiety and EWT. Accuracy is poor at high and low levels of anxiety, and is best at moderate levels. Deffenbacher et al (2004) studied anxiety through a meta-analysis and said the graph should look like this: Christianson and Hubinette (1993) questioned 58 witnesses of real-life bank robberies in Sweden and found that those threatened in some way had improved recall and remembered more details. This was also true 15 months later. This means that in real-life anxiety may increase accuracy of EWT. Weapon-focus effect Johnson and Scott (1976) Ppts heard a discussion in an adjoining room. Condition 1: a man exited with a pen and greasy hands. Condition 2: a man exited with a paperknife and bloody hands. When asked to recall the man from photos, condition 1 were 49% accurate. Condition 2 were 33% accurate. The weapon distracted the witness away from the person holding it. Evaluation Loftus et al (1987) found by following eye movements that the eyewitness’s eyes are physically drawn towards the weapon and away from the face. Peters (1988) found that participants attending a routine inoculation were able to identify a researcher easier than a nurse from photographs. This supports the weapon focus effect. An alternative graph has been suggested to show the relationship between anxiety and EWT. This is called the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Cognitive Interview AO1 AO2 Strengths Fisher et al (1987) studied standard Report Fisher and Geiselman Köhnken et al (1999) carried out a meta-analysis of interviews conducted by real officers reviewed research an 53 studies and found that the CI gained 34% more Everything in Florida and found that they were information than the SI. found that people make Stein and Memon (2006) used female cleaners in aimed at revealing facts, and when weregiven better EW’s Brazil to test the accuracy of the CI. They watched a characterised by: cues. video of an abduction and it was found that more Mental •Brief questions, which yield brief correct information was obtained from witnesses through the CI. Reinstatement Components 1&2 responses, lacking in detail Mello and Fisher (1996) found that when CI and check for consistency •Closed questions, yielding brief of normal interview techniques were tested on both recall older adults’ (72 years) and younger adults’ (22 responses years) memory, CI was better for both. But the Change the •Questions being out of sequence with advantage was more significant for the elderly. Components 3 & 4 how Order witnesses remember events Weaknesses retreives information •Interruptions & distractions, which No longer just one procedure, but many. through different routes Police do not use all of the components. break concentration in memory and is a more Kebbell and Wagstaff (1996) found that using the CI •Not allowing to talk Change the witnesses productive formfreely, of takes more time and police use strategies to limit yielding information which lacks detail questioning EW’s reports to only what they feel is necessary. Perspective Detectives receive only 4 hours of training in the CI. Strategies for Memory Improvement Verbal mnemonics Visual imagery mnemonics Acronyms Method of loci ROYGBIV (rainbow colours) Acrostics My Very Easy Method Just Speeds Up Naming Planets Rhymes Peg words Narrative Chaining Alphabet to the tune of ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’ Chunking To remember phone numbers/postcodes EVALUATION •Gruneberg (1973) found 30% of psychology students use mnemonics to revise for final exams. •Glidden et al (1983) found verbal mnemonics were effective with children with learning disabilities. •Most research has been conducted in labs. Studies in real-life settings (e.g. classrooms) show mixed results, for example, mnemonics are useful for teaching foreign language vocabulary, but may not be so effective at actually speaking in a foreign language. •Mnemonics work through rehearsal and organisation. •Organisation is also important, this helps the brain find the information more quickly. •Elaborative rehearsal is the process of giving something a meaning, and strategies such as mind maps work well for this.