A x - Cloudfront.net

advertisement

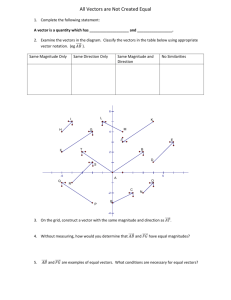

Doing Physics—Using Scalars and Vectors Scalars Many physical quantities can be described completely by a number and a unit. For instance, the mass of an object might be 6 kg, and its temperature 30 C. When a physical quantity is described by a single number, we call it a scalar quantity. Some scalar quantities: mass, temperature, time, density, electric charge, speed A scalar can be positive, negative, or zero. Examples: 0 seconds, 4 kg, 15 inches, a volume of 2 gal. Vectors While many quantities that we meet in physics are scalars, there are others that are not. For these quantities, a single number tells only part of the story. For the scalars that we gave above, we didn’t need to specify any direction. This isn’t always the case. A quantity that deals inherently with direction is called a vector quantity. Some vector quantities: velocity, force, electric field, acceleration, displacement Vectors To fully describe the motion of an airplane, we have to say not only how fast it is moving, but also in what direction. And to describe a force, in addition to giving its magnitude we need to specify the direction in which the force acts. These examples, velocity and force, show that vectors quantities have both magnitude and direction. The magnitude of a vector gives us the size, or the “how much.” Because size can never be negative, the magnitude of a vector cannot be negative. The direction of a vector tells us the orientation of the quantity; it tells us the way the quantity points in space. The direction might be specified as an angle, like 30˚, or by something like “northwest”, or by saying “to the left.” A vector quantity is not complete until both its magnitude and direction are specified. Conceptual Check There are places where the temperature can be +20 C at one time, and -20 C at another time. Does the sign of the temperature indicate a direction? Is temperature a vector quantity? Displacement Vectors The first vector quantity we need to talk about is displacement. Displacement is simply the change in position of an object. A displacement vector starts at an object’s initial position and ends at its final position. It doesn’t matter what the object did in between these two positions. A displacement vector is always a straight line, no matter how curved or squiggly the actual path of motion is. (All vectors are straight lines) This means that displacement is not the same thing as distance. If one travels for a great distance, but comes back to where they started, then their displacement is zero! What does a displacement vector tell us, if not the distance? Its magnitude tells us how far you ended up from where you started (the “straight-line” distance). Its direction tells us which way you moved overall. Representing Vectors The previous example shows that a vectors can be conveniently represented as an arrow. This is the case since an arrow has a magnitude (how long the arrow is) as well as a direction (the way the arrow points). This graphical or pictorial representation will come in handy later on. The velocity of this car is 100 m/s (magnitude) to the left (direction). This boy pushes on his friend with a force of 25 N (magnitude)to the right (direction). Note that while arrows have a magnitude and direction, they don’t have a particular location. That is, vectors have no home. A vector can be moved about and still be the same vector, as long as its length and direction don’t change. So this vector is the same as this vector Two vectors are equal when they have exactly the same magnitude and exactly the same direction. Though vectors have both a magnitude and a direction, they do not have a “home.” That is, we can slide them around as long as we don’t change the size or direction of the vector. Vectors have no home! Although they have the same magnitude (or length), these two vectors are not equal, since they point in different directions. Although they have the same direction, these two vectors are not equal, since they have different magnitudes. Two vectors are equal when they have exactly the same magnitude and exactly the same direction. Vector Notation Because vectors are different from ordinary numbers (scalars), we label them in a special way. Labelling Vectors In the textbook, vectors are given a letter name in bold and with an arrow over them. In your hand-written work, indicate a vector with an arrow over the name of the vector. A Notice that it is not A The arrow above the letter always points to the right, regardless of the direction of the vector. Important: When you write a symbol for a vector, always put an arrow over it. If you don’t put an arrow, than the symbol represents a scalar, and vectors and scalars are very different! ⟶ Thus r and A are symbols for vectors, whereas, symbols for scalars. ⟶ In fact, r and A r ⟶ and ⟶ A, without the arrows, are are how we denote the magnitudes of the vectors. Magnitude of ⟶ A = ⟶ |A| = A Vector Math Calculations with scalar quantities use ordinary arithmetic. For example, 5 kg + 8 kg = 13 kg or 9 s – 5 s = 4 s. Vector calculations, on the other hand, do not use ordinary arithmetic. Consider, for example, our friend Sam, who walks along 12th Street and then goes down the bike path: The final result is the same as though Sam had started at his initial position and undergone a single displacement, as shown. Since the two individual displacements, if taken together, result in the same single displacement, we write the vector equality as shown. We call the single vector the vector sum or the resultant or the net vector. Notice that the magnitude of the vector sum is not equal to the sum of the individual magnitudes. Question: In what situation is the magnitude of the vector sum equal to the sum of the individual magnitudes? Adding Vectors We can use the fact that vectors have no home to help us add vectors. (2) Then draw the resultant vector⟶ ⟶ from the tail of D to the tip of E. (1) Slide the tail of⟶the second vector, E, to the ⟶ tip of the first vector, D. This is the tail-to-tip method. Adding Vectors A second way to add vectors is the parallelogram method. (1) Put the vectors tail to tail. (2) With dashed lines, mark the parallelogram. (3) The resultant vector then points from the tails to the opposite corner, along the diagonal. This is the parallelogram method. Scalar Multiplication Recall that a scalar is a single number (often with some unit), which can positive, zero, or negative. Question: What might you guess happens when we multiply a vector by a scalar? We can change the length (the magnitude) of a vector by multiplying it by a scalar. We generally use lower case letters for scalars: a, b, c, and so on. Note that we cannot change the direction of a vector with scalar multiplication. The exception to this is when multiplying by a negative scalar, as we’ll see. (To change the direction of a vector in a general way, we need matrix multiplication.) Multiplication by a positive scalar: (1) If the scalar is greater than one, scalar multiplication will stretch a vector, making it longer (2) If the scalar is less than one (but positive), scalar multiplication will shrink the vector, making it shorter. A 2A 1 2 A Multiplication by a negative scalar: (1) If the scalar is negative and its absolute value is greater than one, scalar multiplication will flip and stretch a vector. (2) If the scalar is negative and its absolute value is less than one, scalar multiplication will flip and shrink a vector. A 2 A 12 A The definition of multiplication by a negative scalar provides the basis for defining vector subtraction. ⟶ ⟶ Consider the vector subtraction A – B. ⟶ ⟶ To carry this out, we just add A and (– B). ⟶ ⟶ ⟶ ⟶ A – B = A + (–B). Subtracting Vectors Graphically Vector worksheet Vector addition and multiplication by a scalar Coordinate Systems and Vector Components So far we’ve worked with vectors graphically, using pictures to show scalar multiplication and vector addition and subtraction. The graphical approach is helpful in getting a qualitative sense of the motion—the direction of the acceleration, for instance—but it isn’t especially good for an exact description of an object’s motion. The graphical approach We now want to develop some ideas which will allow us to work with vectors in a more quantitative way, so that we can do some real calculations with real numbers. To this end, we lay out here the basics of coordinate systems and components. We will usually use Cartesian coordinates, the familiar rectangular grid with perpendicular axes. As usual, we label the positive end of each axis. Component Vectors We can resolve (or decompose) any vector into two perpendicular component vectors. One of these component vectors is parallel to the x-axis, and we label it Ax The other component vector is parallel to the y-axis, and we label it Ay Notice that the vector A is the vector sum of Ax and Ay . A Ax Ay ⟶ The vector Ax is called the x-component vector. ⟶ ⟶ Ax is the projection of A along the x-axis. ⟶ The vector Ay is called the y-component vector. ⟶ ⟶ Ay is the projection of A along the y-axis. Components ⟶ Suppose we have⟶ a vector A that has been resolved into ⟶ component vectors Ax and Ay parallel to the coordinate axes. We can describe each component vector with a single number (a scalar) called the component (which is different from a component vector!). ⟶ ⟶ Ax = The x-component of the vector A. | Ax | is the magnitude of Ax Ay = The y-component of the vector A. | Ay | is the magnitude of Ay. ⟶ ⟶ The components Ax and Ay tell us how long the component vectors are, and in which direction they point. The direction is captured in the sign (+ or –) of the components. Note Ax and Ayare component vectors; they have a magnitude (which is always positive) and a direction. Ax and Ay are components. They are numbers (with units) that can be positive or negative. Ax and Ay are not the magnitudes of Ax and Ay. | Ax| is the magnitude of Ax . |Ay| is the magnitude of Ay . Vector worksheet Resolving vectors into components opposite hypotenuse adjacent cos hypotenuse opposite tan adjacent sin To remember this, we can use the helpful mnemonic soh-cah-toa: soh-cah-toa o(pposite) sin h(ypotenuse) a(djacent ) cos h( ypotenuse) o( pposite) tan a (djacent ) Decomposing a vector into its x- and y-components. The y-component of A The x-component of A Note When it comes to figuring out the angle and the signs of the components, always draw a picture to guide you! Each decomposition requires that you pay close attention to the direction in which the vector points and the angles that are defined. It’s generally best to use angles between 0 and 90 (for which sine and cosine are non-negative) and to then put in a negative sign “by hand.” Draw a picture with coordinates, label the angle, label the components. Calculate and check! ⟶ Example. Resolve A into its x- and y-components. ⟶ A, A = 14 Ay will be positive y = 40 140 Ax will be negative x Answer. It’s up to us which angle we choose. Let’s work with the angle between the vector and the negative x-axis. Call it . ⟶ We’re given that the magnitude of A is 14. Ax A cos 14 cos 40 14(.766) 10.72 Ay A sin 14sin 40 14(.643) 8.99 Notice that we put in the negative sign “by hand” for Ax since we knew from the picture that it would be negative. How could we check our values? Example. Find the x- and y-components of the acceleration vector shown here. Prepare: Draw a picture, labeling the components and angle. On the picture, note the signs of the components. Solve: Both the x- and y-components are negative, so we have ax a cos 30 (6.0 m/s 2 ) cos 30 5.2 m/s 2 a y a sin 30 (6.0 m/s 2 )sin 30 3.0 m/s 2 Asses: The units of the components ax and ay are the same as the units of the acceleration vector. Notice that our picture guided us in knowing what signs to put in for the calculations. Checking Understanding Ax is the __________ of the vector A. A. B. C. D. E. magnitude x-component direction size displacement Answer Ax is the __________ of the vector A. B. x-component Checking Understanding Which of the vectors below best represents the vector sum P + Q? Slide 3-13 Answer Which of the vectors below best represents the vector sum P + Q? Slide 3-14 Checking Understanding Which of the vectors below best represents the difference P – Q ? Answer Which of the vectors below best represents the difference P – Q ? Slide 3-16 Checking Understanding Which of the vectors below best represents the difference Q – P? A. B. C. D. Answer Which of the vectors below best represents the difference Q – P ? B. What are the x- and y-components of this vector? A. B. C. D. E. 3, 2 2, 3 -3, 2 2, -3 -3, -2 What are the x- and y-components of this vector? B. 2, 3 What are the x- and y-components of this vector? A. B. C. D. E. 3, 4 4, 3 -3, 4 4, -3 3, -4 What are the x- and y-components of these vectors? E. 3, -4 The following vector has length 4.0 units. What are the x- and y-components of this vector? A. B. C. D. E. 3.5, 2.0 -2.0, 3.5 -3.5, 2.0 2.0, -3.5 -3.5, -2.0 The following vector has length 4.0 units. What are the x- and y-components of this vector? B. -2.0, 3.5 The following vector has length 4.0 units. What are the x- and y-components of this vector? A. B. C. D. E. 3.5, 2.0 2.0, 3.5 -3.5, 2.0 2.0, -3.5 -3.5, -2.0 The following vector has length 4.0 units. What are the x- and y-components of this vector? E. -3.5, -2.0 Show that the x- and y-components of a vector don’t depend on the angle we use to describe its direction. y Ax Ay 20 70 Ax x Ay A, magnitude = 8 units Using 20 Using 70 Ax = 8 cos(20) = 7.52 Ax = 8 sin(70) = 7.52 Ay = - 8 sin(20) = - 2.74 Ay = - 8 cos(70) = - 2.74 Notice that we could also use the “standard position” angle. In this case, we don’t need to put the negative sign in by hand. This is because the sine and cosine functions will take care of the signs for us. y 340 x A, magnitude = 8 units Ax = 8 cos(340) = 7.52 Ay = 8 sin(340) = - 2.74 Vector worksheet Using trigonometry with vectors Working with components We’ve seen how to add vectors graphically, but there’s an easier and more accurate way . . . using components! Consider the vectors shown below. B B By The component vectors for B are then: A Bx A Ay The component vectors for A are then: Ax Let’s look at the vector sum C = A + B below: B B A A C=A+B C=A+B Cx B Ay B By Bx A Ax By A Ay Ax Bx Cy We can see that the component vectors of C are the sum of the component vectors of A and B. The same is true of the components: Cx = Ax + Bx and Cy = Ay + By. Adding vectors using components In general, if D = A + B +⟶ C + . . . , then the x- and y-components of the resultant vector D are ⟶ ⟶ ⟶ ⟶ Dx = Ax + Bx + Cx + . . . Dy = Ay + By + Cy + . . . In words: To add vectors, add their like components. This method of vector addition is an algebraic approach, rather than our previous graphical methods. Example. Suppose C = A + B. Vector A has components Ax = 5, Ay = 6 and vector B has components Bx = 4, By = 2. (a) What are the x- and y-components of vector C ? (b) Draw a coordinate system and on it show vectors A, B, and C. Answers: (a) Cx = Ax + Bx = 5 + 4 = 9 Cy = Ay + By = 6 + 2 = 8 y (b) B A C x Example. A bird flies from 100 m due east from a tree, then 200 m northwest (that is, 45 west of north). What is the bird’s net displacement? Answer: Prepare. Let’s draw a picture with the bird starting out at the origin. We’ll call the first flight vector A, and the second flight vector B. Then the total displacement will be C = A + B. (example continued) It may be helpful to redraw this picture with all of the tails at the origin, as shown below: Solve. To add the vectors algebraically, we need their components. From the picture we find: Ax = 100 m Bx = -(200 m) cos 45 = - 141 m Ay = 0 m By = (200 m) sin 45 = 141 m Put in negative sign by hand Cx = Ax + Bx = 100 m + (-141 m) = - 41 m Cy = Ay + By = 0 m + 141 m = 141 m Cy 1 141 m tan tan 74 C 41 m x C Cx 2 C y 2 (41 m)2 (141 m)2 147 m 1 Vector worksheet Adding vectors by components