File

advertisement

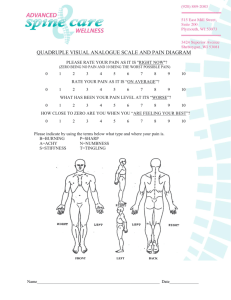

Haley Bryson Joint Manipulation Therapy 03/20/2013 Joint manipulation is a type of therapy directed toward the joint, in most cases synovial joints, and is used for many purposes 1. This technique is not a new concept; it has been dated back to Hippocrates 1. This type of therapy provides a passive movement with some force at the joint and this manipulation is suggested to achieve therapeutic effects 1-9. Manipulation is different than mobilization in that with mobilization it is under the control of the patient while manipulation occurs at such a high speed that the patient cannot stop the motion 1. It is suggested that joint manipulation can decrease pain 1, increase pressure pain thresholds, inhibit motor neuron activity 2, and increase the force and activation within a muscle 3. While the patient is receiving joint manipulation therapy, they may hear a cracking sound which is known as a cavitation 1. This noise is normal for this technique and is usually caused by an expansion of gas within the joint followed by the collapse of the gas which is what creates the cracking sound 1. This is why it is believed that this technique may increase joint mobility, but at the same time one must use caution because doing this repeatedly may cause an increase in thickness at the joint capsule or it may cause the joint to become stiff1. The indications for using joint manipulation include pain that seems to be coming from within the joint 1. The second is a hypomobile joint in comparison to the contralateral side1. The contraindications/precautions for joint manipulation include hypermobile joints, osteoporosis, joint replacement that has not been able to be moved through a full ROM yet, tuberculosis, a grade 3 ligamentous sprain, joint effusions, recent fractures, herniated disc, osteomyleitis, osteoarthritis, pregnancy, severe scoliosis, and malignancy 1. It is suggested that if the clinician is not definitive as to whether or not to use this therapy technique, then do not use it1. In the article Sacroiliac Joint Manipulation Attenuates Alpha-Motoneuron Activity in Healthy Women: A Quasi-Experimental Study by Orakifar et. al. it is said that joint manipulation has been studied as a way to produce an inhibitory response that decreases activity in motor neurons and affect how pain is processed2. Most of the studies that were examined, however, have looked at the effectiveness in the superior spinal column. Therefore, the purpose of the study is to see if joint manipulation will create an inhibition of a motor neuron activity and if the joint manipulation will increase the pressure pain threshold within the SI joint2. The study had 20 female participants, ages 18-30 years old2. There was one researcher who recorded the pressure pain threshold in the participants; another measured activity within the tibial nerve and a separate researcher performed the joint manipulation. Before the joint manipulation was performed the researchers recorded a maximal M wave response, 10 maximal H-reflexes, and 3 pressure pain threshold baselines. Following the joint manipulation therapy the H-reflexes were again tested every 10 seconds for 90 seconds after the therapy and then at 5, 10, 15, 20 minutes following joint manipulation. The M-wave was also tested immediately following the H-reflex testing. The pressure pain response was also measured at different times post joint manipulation at 1, 5, 10, and 15 minutes2. It was found that SI joint manipulation, the ratio of H reflex baseline and the M wave baseline were significantly decreased for up to 20 seconds after the joint manipulation was performed. The pressure pain threshold was shown to decrease, but this finding was not statistically significant at any other the measured times2. This information was in line with previous research found by the authors that suggests that joint manipulation creates a decrease in function of the a motor neuron. However, it did not fall in line with one of the studies that suggested that there is a 15 minute period with a motor neuron inhibition2. This study was an intervention based study, but looked at only women with no prior history of low back injury or pain. There was no control group, but the study was a blind study because one researcher measured H-reflex throughout, one measured M-waves throughout and the other performed the joint manipulation technique. This population is in some ways similar to the population that we will see, as they were considered healthy women ages 18-30, but the study did not include males and was not done on individuals with SI joint pathology. This study was published in 2012 in the Arch Phys Med Rehab journal. The procedures seemed to be one of the only strong parts of this study because the researchers looked at what they were measuring at multiple times after the treatment and compared them to the baseline measures. They would have high intrarater reliability because one person performed one measure throughout the study. Data collection techniques were proven to be reliable and valid. The results for the H-reflexes were proven to be statistically significant, though they do not seem to be clinically significant. Since the population was only healthy women, this does not include the population we would be working with. While we do work with women, the population that will be receiving this type of therapy will be individuals with some kind of pathology. Joint manipulation is a very cost effective method as it does not require any equipment. However, the results of this study showed that the only significant effects lasted up to 20 seconds. The short 20 second inhibition of motor neurons does not seem to outweigh the time that will be spent doing the joint manipulation therapy2. In the article Lumbopelvic Joint Manipulation and Quadriceps Activation of People With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome by Grindstaff et al. it states that study is looking to see the effects of joint mobilization and manipulation on PFPS3. Specifically, it is looking to see if there is more activation and/or strength within the quad after the lumbopelvic region is treated with high grade and low grade joint manipulation and mobilization 1 hour after the treatment3. There were 48 volunteer participants with PFPS. Quadriceps force and activation were measured 20, 40 and 60 minutes after intervention. Participants began with 2 maximal voluntary contractions with electrical stimulation and then another to make sure that they were able to generate the same maximal voluntary contraction on their own. They were then instructed to do 3 more maximal voluntary contractions with visual feedback; meaning that they could see their own force output and then oral encouragement. The participants then jogged and ran for about 7-8 minutes. Participants were then randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups; the high grade joint manipulation and mobilization, side-lying PROM, and prone extension PROM. Once patients received their assigned treatment they again ran for 2-3 minutes and activation and force output was measured. Data was then collected at the time intervals above3. There was no difference between which treatment patients received and the amount of force or activation that was achieved. Although there were some differences in force and activation over the time intervals when the data was collected, the force output of the quad did not change immediately after the last bout of running. Instead, the force output declined at the 20, 40, and 60 minutes post intervention. Activation of the quad was found to decrease immediately after the intervention and was found to be the same as the baseline measures in all of the time intervals following3. The results showed that the activation and force output really did not change or decrease over the course of this study. It is thought that this could possibly be due to fatigue. This study was also looking at running mechanics, hence the reason why the participants ran twice during the intervention, which is what could have contributed to the fatigue. It is also assumed that every participant was giving their maximal output during the trial, when in fact they may not have been. These findings do not suggest that force or activation of the quad were affected by joint manipulation3. In this study, one of the mentioned limitations was that they did not have a true control group that didn’t receive any treatment so they were really just comparing within different interventions. This population may include a portion of the population that we will be working with. There was no given age range, but the study mentioned that the mean age was 24.6 years + or - 8.9 years, similar to the population we work with, but not quite the same. Another limitation was that the PFPS was self diagnosed, patients had to fit into a certain criteria, meaning they had to be able to reproduce their symptoms by compressing the patella, going up and down stairs, performing isometric quad contraction, performing a squat, and/or long periods of sitting. The study was published in 2012 in The Journal of Athletic Training. Procedures were performed the same way for everyone and the interventions were described in a way that one could easily reproduce the intervention. Quad activation was measured by EMG and force output was measured through a force plate, both are considered to be reliable and valid. I do not find these results to be clinically significant because it was found that all three interventions essentially had the same outcomes; none of which were in favor of the patient. I would not want to spend time doing any of these treatments when none seemed to be able to improve the quad activation or the force output of the quad3. The article Immediate effects of a tibiofibular joint manipulation on lower extremity Hreflex measurements in individuals with chronic ankle instability by Grindstaff et. al. states that individuals with chronic ankle instability tend to have a decrease in activation in the peroneus longus and the soleus4. This is thought to be caused by guarding, a reflexive response to protect the area. In this study the researchers are looking to see if a proximal and/or distal joint manipulation will have an effect on the activation of the peroneus longus and the soleus4. There were 43 subjects used for the study with an average age of 25.6 ± 7.7 years, all of whom had chronic ankle instability and had a 5º decrease in ankle dorsiflexion ROM in comparison to the contralateral limb. The H-reflex and M-wave were measured using surface EMG. The H-reflex and M-wave baseline measures in the peroneus longus and the soleus muscles were collected first. These measures were recorded three times to get a max H-reflex and to get the max M-wave, then the two max numbers were combined and used as an H-reflex to M-wave ratio. After this information was acquired, the participants were assigned to one of three treatment groups; proximal tibiofibular joint manipulation, distal tibiofibular joint manipulation, and no treatment. There were two different physical therapists that performed the joint manipulation and one researcher who recorded all the information. The H-reflex and the M-wave were recorded immediately after the intervention then 10, 20, and 30 minutes after the intervention4. When looking at the peroneus longus muscle the H/M ratio over time was not statistically significant over time, but when the groups were combined at 20 and 30 minutes post intervention, there was a significant decrease in the H/M ratio. When looking at the soleus muscle the H/M ratio over time was statistically significant between groups. There was a statistically significant increase in the H/M ratio when performing the distal joint manipulation at every time period except at 20 minutes post intervention. When the groups were combined there was a statistically significant decrease in the soleus H/M ratio at 30 minutes post intervention. This means that when the distal joint manipulation was performed, there was an increase in the activation of the H reflex and M wave, but no intervention seemed to do this at the peroneus longus4. This group is again similar to the group that we most commonly work with, about the 1830 years of age range. This article was published in The Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology in 2011. The joint manipulations were all performed by 1 of 2 therapists and then all of the recorded outcome measures were taken by the same person. I think this is a strong suit for this study. One of the things that also makes this article stand out from some of the others is that there was a true control group that did not receive any treatment at all. Chronic ankle instability was determined by FAAM survey (score of 85%) and three on the ankle instability instrument, both were valid and reliable for determining functional ankle instability. The soleus muscle was the only one that had a statistically significant increase in activation post joint manipulation. However, as mentioned by the researchers, the clinical implications of this are unknown at this time. I would say that this is a step in the right direction and perhaps patients with chronic ankle instability may benefit from joint manipulation and then a strengthening regimen for the soleus. Perhaps these steps would decrease instability. To me, this treatment is effective if the patient would benefit from an increase in soleus muscle activation; otherwise, the results of this study suggest that there are really no other benefits4. The article The immediate effects of atlanto-occipital joint manipulation and suboccipital muscle inhibition technique on active mouth opening and pressure pain sensitivity over latent myofascial trigger points in the masticatory muscles by Oliveira-Campelo et. al. says that previous research on this area of the body suggests that joint manipulation therapy will help to alleviate trigger point pain within the area5. The authors of this study have found no prior research of this technique used on the trigeminal muscles. The purpose of this study is to look at the effects of atlanto-occipital joint manipulation and the effects on the pressure pain sensitivity, as well as active mouth opening at the masseter and temporalis muscles5. There were 122 participants recruited for this study ages 18-30; these were all volunteer based. All of the participants had to be screened for a trigger point in the area and only those with the trigger points were included in this study. The participants were randomly assigned to groups that included the joint manipulation group, the suboccipital release group and the no intervention group. The two treatment groups were both treated by the same clinician; one received the manipulative therapy and the other received the suboccipital release, while the control group came in and stayed on the table for the amount of time it would take to do a treatment and then their “post intervention” data was collect5. It was found that there is a statistically significant increase in the pressure pain threshold after the joint manipulation therapy was performed. The authors also found that there was an increase in the AROM opening of the mouth. It is however suggested by the authors that these results are most likely not clinically relevant at this point because of the small effective size. However, it is a starting point for more research and may be used to see if we as clinicians are able to provide the same results. The results were also not looked at over time and were only looked at immediately following the intervention so the results may or may not be very temporary5. This study looked at a similar population to the population that we will be working with. It was published in The Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy in 2010. The procedures were performed by one clinician and one who did data collection, so this was a double-blinded study. The outcome measure for pressure pain threshold was done with an algometer which has been proven reliable and valid for recording pressure pain threshold. The active mouth opening measurements were performed with a tape measure, but this technique has been recorded as having high intrarater reliability. This treatment seemed to be successful in increasing the pressure pain threshold and increasing the active mouth opening. However, it seems to be only a temporary fix and not a long term solution to the problem. For temporary pain relief, I think this is a good treatment, but looking to the future I think other methods that could get to the root of the problem and solve it would better serve the patient5. It is stated in the article The effect of two manipulative therapy techniques and their outcome in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome by Kamali et. al. that there have been past studies that joint manipulation at the SI joint will help to decrease inhibition and increase the threshold of motor neurons6. So far the authors have no knowledge of a study that has performed comparing two different joint manipulation interventions at the SI joint. The purpose of this study is to compare the difference between two different types of joint manipulation interventions and their effects at the SI joint6. This study included 32 female patients ages 20-30. These women were already attending physical therapy for low back pain, but had not received any joint manipulation therapy at the SI joint for at least one month. The participants were then randomly assigned to either the SI joint manipulation therapy group or the lumbar and SI joint manipulation therapy group. The patients were then asked their pain level on a scale of 1-100. Then they were also asked to fill out the Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire which determined functional disability. These two outcome measures were first recorded immediately after intervention, 48 hours later, and one month later6. It was found in both the SI joint manipulation therapy group and the lumbar and SI joint manipulation therapy group, that there was a statistically significant decrease in the visual analog scale of pain at all time intervals following intervention. It was also found that there was a statistically significant improvement in functioning at 48-hours and one month post intervention. There was no difference between functioning or pain values over time between the SI joint manipulation only and the SI joint and lumbar joint manipulation therapy groups6. There is one extraneous variable that was not mentioned throughout the study and it was that the patients were recruited from a physical therapy clinic. It was not mentioned if this factor was somehow controlled for or if the patients were asked to stop going to therapy during the course of their treatment. If this is not accounted for, it cannot be determined whether or not the long term effects from this study were attenuated through the intervention or through physical therapy. This study also had no control group to compare findings to, so perhaps time could have been a factor in the functional improvements seen within groups. The population was only females which mean that the results of this study cannot really be generalized to males. The data collection techniques were proven to be reliable and valid. The procedures were performed by the same clinician in the same way, so it seems that the procedures were performed fairly well. The results of this study were clinically significant, but not necessarily clinically significant. If the patients were getting better because of the activities that were being performed at the physical therapy clinic instead of the onetime joint manipulation therapy technique, this to me suggests that the immediate pain release is beneficial for the patient and may help them with pain control, but overall should possibly be used in conjunction with physical therapy6. In the article Effects of a Proximal or Distal Tibiofibular Joint Manipulation on Ankle Range of Motion and Functional Outcomes in Individuals With Chronic Ankle Instability by Beazell et. al. the authors suggest that chronic ankle instability affects about 30% of people who have suffered from a lateral ankle sparin7. It is suggested here that part of the reason is because of the way the fibula is positioned. The purpose of this study is to look at the effects of a proximal and distal joint manipulation at the tibiofibular joint on functional ability and dorsiflexion ROM7. Participants were volunteers that qualified as having CAI; the authors used 43 participants to complete the study. The participants had to fill out the FAAM, which has high reliability for functional ankle instability. This was the first task and was used as a baseline score. Then ankle weight bearing ROM dorsiflexion was measured, participants then completed the single leg stance portion of the BESS test on a foam pad, and last the step down test. The participants were then assigned to the proximal tibiofibular joint manipulation group, the distal tibiofibular joint manipulation group, and the control group. The baseline score collector was blinded as to which treatment group the participants were in. The clinician doing the joint manipulation was also blinded to the previous scores of each participant. The outcome measures were then taken again immediately following the procedure and then 7, 14, and 21 days after the intervention. At each time point, the patient again received the intervention and completed the same outcome measures7. It was found that when all the groups were combined, across time, there was a significant increase in ankle dorsiflexion. There were no statistically significant differences between the any of the groups across time when comparing the BESS test, step down test, or the FAAM7. This article was published in 2010 in The Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy. In this study the participants were volunteers from the college and a nearby clinic. So these demographics are similar to the patients that we would be working with. The procedures were done to the best of the researchers abilities. The researchers were double blinded and all assessments were used with the same equipment and in the same room. All the interventions were done by one clinician and all of the outcome measures were recorded by a different clinician throughout the entire process. In this study it was found that the only statistically significant difference was found in the increase in ankle dorsiflexion which occurred over all groups. It is suggested by the authors that this could have been due to all of the functional testing that was done by each participant. The step down test and weight bearing dorsiflexion ROM measure both require the patient to go to their end range of motion in dorsiflexion. This is perhaps a variable they should have controlled for and then compared the improvements of the joint manipulation groups and the control group. I would not use this for an athlete with chronic ankle instability as it has been shown here in two different studies to be rather ineffective; especially since the only improvements seen within the groups were also seen within the control group7. In the article Effects of lumbopelvic joint manipulation on quadriceps activation and strength in healthy individuals by Grindstaff et. al. it states that previous research has suggested that lumbopelvic joint manipulation has had an effect on the force output and activation of several different muscles8. Most of that research, however, has only looked at the immediate effects. The purpose of this study is to see if lumbopelvic joint manipulation and mobilization will increase the activation and force output of the quad in healthy individuals for up to one hour8. There were 42 participants within the study, all of which were considered healthy and had no history of lumbar spine pathology within the past six months. The researchers then gathered all of the baseline information from each of the participants. This included the quad force output using an isometric contraction using a biopac machine, and then quadriceps activation was recorded using the burst super-imposition technique which stimulates a muscle contraction through an electrical impulse. Following this, the central activation ratio was calculated for each participant. The test leg for each participant was determined by coin toss and participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups; the lumbopelvic joint manipulation group (high grade mobilization group), the lumbar flexion/extension PROM group (low grade joint mobilization) and the prone extension group (sham group). The outcome measures were then again taken immediately after intervention and then 20, 40, and 60 minutes following intervention8. It was determined that there was not a statistically significant difference between the treatment groups and quad activation or force output, nor was there a statistically significant difference between quad force output and activation over time8. It was not mentioned in this study if the clinician performing the intervention was also the one that collected the outcome measures. The upside to this study is that the subjects were blinded because the control group did a prone lumbar extension, which they most likely thought was some kind of intervention that helps to control for some bias. This group is similar to the population that we will be working with, which is about 18-30. However this study only used individuals who were asymptomatic which is not a population we treat. The procedures were done by an experienced clinician on equipment that was proven valid and reliable. The results showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups or in time. This to me seems to be a relatively ineffective way to increase quadriceps force output and activation. Although this treatment is rather cost effective since you do not need to purchase any equipment, if it does not work, it is not worth the time8. It is stated in the article Short-Term Effects of Kinesio Taping Versus Cervical Thrust Manipulation in Patients With Mechanical Neck Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial by Saavedra-hernández et. al. that there are some studies that suggest that cervical pain is becoming almost as prevalent as low back pain9. Most people who suffer from mechanical neck pain seek a physical therapist first and their most common treatment is joint manipulation, although most studies suggest that there seems to be no difference between joint manipulation and no intervention at all. Currently, there is little information on the effects of kinesiotape on mechanical neck pain. The purpose of this study is to determine the short term effects of joint manipulation and kinesio tape on mechanical neck pain9. Participants were patients at a physical therapy clinic in Spain and it was determined that all met the criteria for mechanical neck pain. There were 80 participants recruited for the study with an age range from 18 to 55. Each patient had a baseline outcome measure recorded. The outcome measures included subjective pain level, the Neck Disability Index, a body diagram to determine the location and distribution of pain, and cervical ROM. They were also screened for nystagmus, Horner syndrome, gait abnormailities, and any ligamentous instability in the cervical region. The patients were then randomly assigned to the joint manipulation or Kinesio-taping group. The researcher who collected all of the outcome measures was blinded to which treatment each participant received. Outcome measures were taken at baseline and seven days following the intervention9. It was found that patients who received the joint manipulation therapy had a statistically significant increase in cervical rotation in comparison to the kinesiotape group. It was found that there were no statistically significant changes in cervical flexion, extension, or lateral flexion between the two groups, but both groups showed improvements. It also showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the amount of disability or subjective pain, but both decreased similarly. Five of the patients within the study had adverse effects; three from joint manipulation including an increase in pain and fatigue, and two from the kinesiotape with reported skin irritation; the symptoms subsided after 24 hours. It is suggested by the authors that the changes in cervical ROM were very small and of little clinical significance9. All of the outcome measures were considered valid and reliable measures for their particular outcomes. The procedures were done the same for all persons, except for the obvious difference in intervention. The population was not similar to the group we would be working with; the study did include a younger population but the average age for each group was 45 years old. This experiment was double blinded and was not compared with a control group, so it cannot be determined if the improvements were because of time or because of the actual intervention. Which brings up the point that these participants were all being seen for mechanical neck pain in a physical therapy clinic and it was not mentioned if they stopped therapy while participating in this study or not, which also means that a control group could have been found to have similar results if they were participating in a similar rehab program. This study was published in the Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy in 2012. As the authors mentioned the differences in cervical ROM for both groups were not really clinically significant as they were very small, but the change in rotation was greater for the group with the joint manipulation. Both groups showed similar statistically significant improvements in subjective pain reports and disability. The clinical relevance of this to me means that in this particular scenario, if the patients’ main complaint is pain, I would most likely use the Kinesiotape intervention because the adverse effects were just skin irritation versus an increase in pain. On the other hand if the patient came in complaining of a lack of ROM, I would try the joint manipulation because both improved similarly with more rotational benefits coming from joint manipulation. If cost were a factor, I would also choose the joint manipulation therapy as there is some cost involved with kinesiotape. I wouldn’t use either of these methods as a sole treatment for a patient; it would be in conjunction with stretching and strengthening activities9. In the athletic training world I feel that this rehab technique is not necessarily useful. According to this body of research, it is determined that the treatment was relatively ineffective; in most cases only as effective as a control group with no intervention, or had very little effect and for relatively short periods of time[2-9]. The good thing about joint manipulation therapy is that it does not require any equipment and it also does not require a lot of time; most of these studies indicated 1-2 minutes[2,3,7-9]. In most of the articles it was suggested that the previous research indicates that this treatment did have some effects, but I don’t think any of these studies sided with the previous research [2-9]. The further I got into this body of research, the more I thought that this technique seems to be like a “quick fix” and doesn’t really get to the root of the problem, which perhaps could be addressed through a rehabilitation exercise protocol and therapeutic modalities. The bad thing about joint manipulation is that is has a relatively high number of contraindications. With that being said, I don’t necessarily think that we are doing our jobs as clinicians if this is the only “rehab” we are doing with patients. Masking the problem does not make it go away and we are there to get athletes back to what they were before the injury not to just cover it up. I think that used in conjunction with other techniques and if a patients feels that it is beneficial to them, it should be used. Otherwise it is suggested by the majority of these articles that it is essentially ineffective. References: 1. Houglum PA. Therapeutic Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries. 3rd Edition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2010. 2. Orakifar N, Kamali F, Pirouzi S, Jamshidi F. Sacroiliac Joint Manipulation Attenuates AlphaMotoneuron Activity in Healthy Women: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Archives Of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation [serial online]. January 2012;93(1):56-61. 3. Grindstaff T, Hertel J, Ingersoll C, et al. Lumbopelvic Joint Manipulation and Quadriceps Activation of People With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. Journal Of Athletic Training [serial online]. January 2012;47(1):24-31. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013. 4. Grindstaff T, Beazell J, Sauer L, Magrum E, Ingersoll C, Hertel J. Immediate effects of a tibiofibular joint manipulation on lower extremity H-reflex measurements in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Journal Of Electromyography And Kinesiology: Official Journal Of The International Society Of Electrophysiological Kinesiology [serial online]. August 2011;21(4):652-658. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013. 5. Oliveira-Campelo N, Rubens-Rebelatto J, Martí N-Vallejo F, Alburquerque-Sendí N F, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C. The immediate effects of atlanto-occipital joint manipulation and suboccipital muscle inhibition technique on active mouth opening and pressure pain sensitivity over latent myofascial trigger points in the masticatory muscles. The Journal Of Orthopaedic And Sports Physical Therapy [serial online]. May 2010;40(5):310-317. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013. 6. Kamali F, Shokri E. The effect of two manipulative therapy techniques and their outcome in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome. Journal Of Bodywork & Movement Therapies [serial online]. 2012;16(1):29-35. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013. 7. Beazell J, Grindstaff T, Sauer L, Magrum E, Ingersoll C, Hertel J. Effects of a Proximal or Distal Tibiofibular Joint Manipulation on Ankle Range of Motion and Functional Outcomes in Individuals With Chronic Ankle Instability. Journal Of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy [serial online]. February 2012;42(2):125-134. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013 8. Grindstaff T, Hertel J, Beazell J, Magrum E, Ingersoll C. Effects of lumbopelvic joint manipulation on quadriceps activation and strength in healthy individuals. Manual Therapy [serial online]. August 2009;14(4):415-420. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013. 9. Saavedra-hernández M, Castro-sánchez A, Arroyo-morales M, Cleland J, Lara-palomo I, Fernández-de-las-peñas C. Short-Term Effects of Kinesio Taping Versus Cervical Thrust Manipulation in Patients With Mechanical Neck Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal Of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy [serial online]. August 2012;42(8):724-730. Available from: SPORTDiscus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 24, 2013.