Poetry Packet - Ramsey School District

Latino Poetry

The poems in this unit were selected to capture a wide range of experiences from the

Latino culture. The themes in the poems reflect the joys and hardships of the Latino community. They give voice to people who have faced conflicts and challenges, but who have also celebrated the values and traditions of the Latino culture such as the importance of family, community, and heritage. At the same time, you will discover that these poems are about you because they often reflect the experiences of all people, not just Latinos. Through the poets’ musical phrases and powerful images, you will come to better understand yourself and your world.

Section 1: Identity

Each poem in this group expresses the poet’s struggle to establish a sense of his or her own identity. Caught as they are between their Latino heritage and the culture of the United

States, the poets reveal their uncertainty about who they are. In “Affirmations #3, Take Off

Your Mask”, Sandra Maria Esteves, A New York-born poet of Puerto Rican and Dominican heritage, instructs readers to cast aside their outward masks. She encourages them to look within themselves to discover their true identities. Gustavo Perez Firmat was born in Havana,

Cuba, and raised in Miami, Florida. In “Dedication”, he tries to explain his feelings about writing in English rather than in Spanish. In “Child of the Americans”, poet Aurora Levins Morales attempts to define herself in terms of her rich and varied ancestry. In “migrating Notes”,

Josephina Baez speaks of the sense of division she feels as a Dominican living in the United

States. Finally , in “You Call Me by Old Names”, Rhina Espaillat states her preference for being called by names that reflect her present identity, not her past.

“Affirmations #3, Take Off Your Mask” – Sandra Maria Esteves

Study the face behind it.

The one that has no flesh or bones.

The one that feels what the universe feels.

Take off the mask. Discard it.

Useless shell that it is.

An old skin. A cover.

Subject to weather distortions.

See for yourself the you inside no one else can see.

“Dedication” – Gustavo Pérez Firmat

The fact that I am writing to you in English already falsifies what I wanted to tell you.

My subject: how to explain to you that I don’t belong to English though I belong nowhere else, if not here in English.

“Child of the Americans” – Aurora Levins Morales

I am a child of the Americas, a light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean, a child of many diaspora, born into this continent at a crossroads.

I am a U.S. Puerto Rican Jew, a product of the ghettos of a New York I have never known.

An immigrant and the daughter and granddaughter of immigrants.

I speak English with passion: it’s the tongue of my consciousness, a flashing knife blade of crystal, my tool, my craft.

I am Caribeña, island grown. Spanish is in my flesh,

Ripples from my tongue, lodge in my hips: the language of garlic and mangoes, the singing of poetry, the flying gestures of my hands.

I am of Latinoamerica, rooted in the history of my continent:

I speak from that body.

I am not African.

Africa is in me, but I cannot return.

I am not Taína.

Taíno is in me, but there is no way back.

I am not European.

Europe lives in me, but I have no home there.

I am new. History made me. My first language was spanglish.

I was born at the crossroads and I am whole.

“You Call Me by Old Names” – Rhina P. Espaillat

You call me by old names: how strange to think of “family” and “blood,” walking through flakes, up to the knees in cold and democratic mud.

And suddenly I think of people dead many centuries ago: my ancestors, who never knew the dubious miracle of snow….

Don’t say my names, you seem to mock their charming, foolish, Old World touch.

Call me “immigrant,” or Social

Security card such-and-such, or future citizen, who boasts two eyes, two ears, a nose, a mouth, but no names from another life, a long time back, a long way south.

“Migrating Notes” – Josefina Baez

I had no say in coming

I have illusions about going.

Here I never belong about D.R. I just have a thought memories of the past create a false act

Although very near

It’s not so clear.

Now bilingual soul divided

Dominicanhood to this different strangely, richly integrated and harsh reality aging. without realizing rooting

Section 1: Identity

1.

In “Affirmations #3, Take Off Your Mask”, what distinction does the speaker make between the outer and inner selves?

2.

In “Dedication”, “Child of the Americas”, and “You Call Me by Old Names”, what role does spoken or written language play in the way the speakers see themselves?

3.

What illusions do you think the speaker of “Migrating Notes” has about going to the

Dominican Republic? Which lines in the poem best support your conclusion?

4.

Which poem in this group did you find especially meaningful? What made these poems special?

Section 2: Self-Discovery and Family

Through vivid imagery and figurative language, the poets presented in this section express their identities and their cultural heritages. By exploring family relationships and certain Mexican and U.S. customs and beliefs, these poets reveal that their sense of identity is rooted firmly in family and culture.

“My Father is a Simple Man” – Luis Omar Salinas

I walk to town with my father to buy a newspaper. He walks slower than I do so I must slow up.

The street is filled with children.

We argue about the price of pomegranates. I convince him it is the fruit of scholars.

He has taken me on this journey and it’s been lifelong.

He’s sure I’ll be healthy so long as I eat more oranges, and tells me the orange has seeds and so is perpetual; and we too will come back like the orange trees.

I ask him what he thinks about death and he says he will gladly face it when it comes but won’t jump out in front of a car.

I’d gladly give my life for this man with a sixth grade education, whose kindness and patience are true . . .

The truth of it is, he’s the scholar, and when the bitter-hard reality comes at me like a punishing evil stranger, I can always remember that here was a man who was a worker and provider, who learned the simple facts in life and lived by them, who held no pretense.

And when he leaves without benefit of fanfare or applause

I shall have learned what little there is about greatness.

“Nani” – Alberto Rios

Sitting at her table, she serves the sopa de arroz to me instinctively, and I watch her, the absolute mamá, and eat words

I might have had to say more out of embarrassment. To speak now-foreign words I used to speak, too, dribble down her mouth as she serves me albondigas. No more than a third are easy to me.

By the stove she does something with words and looks at me only with her back. I am full. I tell her

I taste the mint, and watch her speak smiles at the stove. All my words make her smile. Nani never serves herself, she only watches me with her skin, her hair. I ask for more.

I watch the mamá warming more tortillas for me. I watch her fingers in the flame for me.

Near her mouth, I see a wrinkle speak of a man whose body serves the ants like she serves me, then more words from more wrinkles about children, words about this and that, flowing more easily from these other mouths. Each serves as a tremendous string around her,

holding her together. They speak

Nani was this and that to me and I wonder just how much of me will die with her, what were the words

I could have been, was. Her insides speak through a hundred wrinkles, now, more than she can bear, steel around her, shouting, then, What is this thing she serves?

She asks me if I want more.

I own no words to stop her.

Even before I speak, she serves.

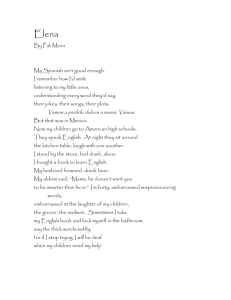

“Senora X No More” – Pat Mora

Straight as a nun I sit.

My fingers foolish before paper and pen hide in my palms. I hear the slow, accented echo

How are yu? I ahm fine. How are yu? of the other women who clutch notebooks and blush at their stiff lips resting sounds that float graceful as bubbles from their children's mouths.

My teacher bends over me, gently squeezes my shoulders, the squeeze I give my sons, hands louder than words.

She slides her arms around me: a warm shawl, lifts my left arm onto the cold, lined paper.

"Señora, don't let it slip away," she says and opens the ugly, soap-wrinkled fingers of my right hand with a pen like I pry open the lips of a stubborn grandchild.

My hand cramps around the thin hardness.

"Let it breathe," says this woman who knows my hand and tongue knot, but she guides and I dig the tip of my pen into that white.

I carve my crooked name, and again at night until my hand and arm are sore,

I carve my crooked name, my name.

“Mamacita” – Judith Ortiz Cofer

Mamacita hummed all day long over the caboose kitchen of our railroad flat.

From my room I’d hear her humm,

Crossing her path, I’d catch her umm.

No words slowed the flow of Mamacita’s soulful sounds; it was humm over the yellow rice, and umm over the black beans.

Up and down two syllables she’d climb and slide—each note a task accomplished.

From chore to chore, she was the prima donna in her daily operetta.

Mamacita’s wordless song was her connection to the oversoul, her link with life, her mantra, a lifeline to her own Laughing Buddha, as she dragged her broom across a lifetime of linoleum floors.

Section 2: Self-Discovery and Family

1.

In the poem “My Father Is a Simple Man”, what does the speaker recognize about his father’s attitude toward life? How does this quality influence the speaker’s own attitude?

2.

In “Nani” and “Senora X No More”, what role does spoken or written English language play in the identities of the two speakers?

3.

In “Mamacita”, what do you think the speaker learns about life from watching her mother work? How does Cofer honor her mother by writing this poem?

4.

Which poem in this group is especially meaningful to you? How does the use of imagery and language assist in their meaning?

Section 3: Discovering Heritage

The following poem explores the differences between what was familiar to the speaker in her homeland and what she found when she came to the United States. In the poem, the speaker remembers the places, the people and the objects that represent her cultural roots.

“My Mother Pieced Quilts” — Teresa Paloma Acosta they were just meant as covers in winters as weapons against pounding january winds but it was just that every morning I awoke to these october ripened canvases passed my hand across their cloth faces and began to wonder how you pieced all these together these strips of gentle communion cotton and flannel nightgowns wedding organdies dime store velvets how you shaped patterns square and oblong and round positioned balanced then cemented them with your thread a steel needle a thimble how the thread darted in and out galloping along the frayed edges, tucking them in as you did us at night oh how you stretched and turned and re-arranged your michigan spring faded curtain pieces my father's santa fe work shirt the summer denims, the tweed of fall

in the evening you sat at your canvas

---our cracked linoleum floor -the drawing board me lounging on your arm and you staking out the plan; whether to put the lilac purple of eastel- against the red plaid of winter-going- into-spring whether to mix a yellow with blue and white and paint the corpus christi noon when my father held your hand whether to shape a five-point star from the somber black silk you wore to grandmother's funeral.

You were the river current carrying the roaring notes forming them into pictures of a little boy reclining a swallow flying

You were the caravan master at the reins driving your thread needle artillery across the mosaic cloth bridges delivering yourself in separate testimonies oh mother you plunged me sobbing and, laughing into our past into the river crossing at five into the spinach fields into the plainview cotton rows into tuberculosis wards into braids and muslin dresses sewn hard and taut to withstand the thrashings of twenty-five years stretched out they lay armed/ready/shouting/celebrating knotted with love the quilts sing on

Section 3: Discovering Heritage

1.

What do the quilts reveal about the women who created them?

2.

How can an everyday object reveal much more about family and heritage?

3.

Which traditions in your family does this poem bring to mind?

Section 4: Balancing Two Cultures

The following poems explore the speaker’s struggle of blending Latino heritage into an American society. Both speakers feel caught between two cultures and express their difficulty in balancing the two.

“Bilingual/Bilingüe” – Rhina P. Espaillat

My father liked them separate, one there, one here (allá y aquí), as if aware that words might cut in two his daughter’s heart

(el corazón) and lock the alien part to what he was—his memory, his name

(su nombre)—with a key he could not claim.

“English outside this door, Spanish inside,” he said, “y basta.” But who can divide the world, the word (mundo y palabra) from any child? I knew how to be dumb and stubborn (testaruda); late, in bed,

I hoarded secret syllables I read until my tongue (mi lengua) learned to run where his stumbled. And still the heart was one.

I like to think he knew that, even when, proud (orgulloso) of his daughter’s pen, he stood outside mis versos, half in fear of words he loved but wanted not to hear.

“Bilingual Sestina” -- Julia Alvarez

Some things I have to say aren't getting said in this snowy, blonde, blue-eyed, gum chewing English, dawn's early light sifting through the persianas closed the night before by dark-skinned girls whose words evoke cama, aposento, suenos in nombres from that first word I can't translate from Spanish.

Gladys, Rosario, Altagracia--the sounds of Spanish wash over me like warm island waters as I say your soothing names: a child again learning the nombres of things you point to in the world before English turned sol, tierra, cielo, luna to vocabulary words-- sun, earth, sky, moon--language closed like the touch-sensitive morivivir. whose leaves closed when we kids poked them, astonished. Even Spanish failed us when we realized how frail a word is when faced with the thing it names. How saying its name won't always summon up in Spanish or English the full blown genii from the bottled nombre.

Gladys, I summon you back with your given nombre to open up again the house of slatted windows closed since childhood, where palabras left behind for English stand dusty and awkward in neglected Spanish.

Rosario, muse of el patio, sing in me and through me say that world again, begin first with those first words you put in my mouth as you pointed to the world-- not Adam, not God, but a country girl numbering the stars, the blades of grass, warming the sun by saying

el sol as the dawn's light fell through the closed persianas from the gardens where you sang in Spanish,

Esta son las mananitas, and listening, in bed, no English yet in my head to confuse me with translations, no English doubling the world with synonyms, no dizzying array of words,

--the world was simple and intact in Spanish awash with colores, luz, suenos, as if the nombres were the outer skin of things, as if words were so close to the world one left a mist of breath on things by saying their names, an intimacy I now yearn for in English-- words so close to what I meant that I almost hear my Spanish blood beating, beating inside what I say en ingles.

Section 4: Balancing Cultures

1.

What do each of these poems reveal about the importance of language?

2.

In what way are both of these speakers struggling with identity?

Section 5: The House on Mango Street

In the novel The House on Mango Street, Cisneros draws on her rich Latino heritage creating unforgettable characters in her sparse prose style. The novel, told in a series of vignettes, tells the story of a young girl Esperanza growing up in a Latino section of Chicago. Her neighborhood is one of harsh realities and harsh beauties as Esperanza struggles with her identity and her feelings of not wanting to belong to her rundown neighborhood. Esperanza’s story is that of a young girl coming into her power, and inventing for herself what she will become.

My Name

In English my name means hope. In Spanish it means too many letters. It means sadness, it means waiting. It is like the number nine. A muddy color. It is the Mexican records my father plays on Sunday mornings when he is shaving, songs like sobbing.

It was my great-grandmother's name and now it is mine. She was a horse woman too, born like me in the Chinese year of the horse—which is supposed to be bad luck if you're born female—but I think this is a Chinese lie because the Chinese, like the Mexicans, don't like their women strong.

My great-grandmother. I would've liked to have known her, a wild horse of a woman, so wild she wouldn't marry. Until my great-grandfather threw a sack over her head and carried her off. Just like that, as if she were a fancy chandelier. That's the way he did it.

And the story goes she never forgave him. She looked out the window her whole life, the way so many women sit their sadness on an elbow. I wonder if she made the best with what she got or was she sorry because she couldn't be all the things she wanted to be. Esperanza. I have inherited her name, but I don't want to inherit her place by the window.

At school they say my name funny as if the syllables were made out of tin and hurt the roof of your mouth. But in Spanish my name is made out of a softer something, like silver, not quite as thick as sister's name—Magdalena—which is uglier than mine. Magdalena who at least can come home and become Nenny. But I am always Esperanza.

I would like to baptize myself under a new name, a name more like the real me, the one nobody sees.

Esperanza as Lisandra or Maritza or Zeze the X. Yes. Something like Zeze the X will do.

Laughter

Nenny and I don't look like sisters ... not right away. Not the way you can tell with Rachel and Lucy who have the same fat popsicle lips like everybody else in their family. But me and Nenny, we are more alike than you would know. Our laughter for example. Not the shy ice cream bells' giggle of Rachel and Lucy's family, but all of a sudden and surprised like a pile of dishes breaking. And other things I can't explain.

One day we were passing a house that looked, in my mind, like houses I had seen in Mexico.

I don't know why. There was nothing about the house that looked exactly like the houses I remembered.

I'm not even sure why I thought it, but it seemed to feel right.

Look at that house, I said, it looks like Mexico.

Rachel and Lucy look at me like I'm crazy, but before they can let out a laugh, Nenny says: Yes, that's

Mexico all right. That's what I was thinking exactly.

Four Skinny Trees

They are the only ones who understand me. I am the only one who understands them. Four skinny trees with skinny necks and pointy elbows like mine. Four who do not belong here but are here. Four raggedy excuses planted by the city. From our room we can hear them, but Nenny just sleeps and doesn't appreciate these things.

Their strength is secret. They send ferocious roots beneath the ground. They grow up and they grow down and grab the earth between their hairy toes and bite the sky with violent teeth and never quit their anger. This is how they keep.

Let one forget his reason for being, they'd all droop like tulips in a glass, each with their arms around the other. Keep, keep, keep, trees say when I sleep. They teach.

When I am too sad and too skinny to keep keeping, when I am a tiny thing against so many bricks, then it is I look at trees. When there is nothing left to look at on this street. Four who grew despite concrete.

Four who reach and do not forget to reach. Four whose only reason is to be and be.

A Smart Cookie

I could've been somebody, you know? my mother says and sighs. She has lived in this city her whole life. She can speak two languages. She can sing an opera. She knows how to fix a TV. But she doesn't know which subway train to take to get downtown. I hold her hand very tight while we wait for the right train to arrive. She used to draw when she had time. Now she draws with a needle and thread, little knotted rosebuds, tulips made of silk thread. Someday she would like to go to the ballet. Someday she would like to see a play. She borrows opera records from the public library and sings with velvety lungs powerful as morning glories.

Today while cooking oatmeal she is Madame Butterfly until she sighs and points the wooden spoon at me. I could've been somebody, you know? Esperanza, you go to school. Study hard. That Madame

Butterfly was a fool. She stirs the oatmeal. Look at my comadres. She means Izaura whose husband left and Yolanda whose husband is dead. Got to take care all your own, she says shaking her head.

Then out of nowhere:

Shame is a bad thing, you know? It keeps you down. You want to know why I quit school? Because I didn't have nice clothes. No clothes, but I had brains.

Yup, she says disgusted, stirring again. I was a smart cookie then.

Section 5: The House on Mango Street

1.

What does the narrator, Esperanza, reveal about herself, her family, and her Mexican American culture in these vignettes? Use one line from each vignette to support.

2.

Why does Esperanza have conflicting feelings about her name? What does Mango Street represent for her?

3.

How does remembering one’s past and exploring it through fiction help a writer? What can you learn about yourself through writing fiction or poetry?