Class #3

advertisement

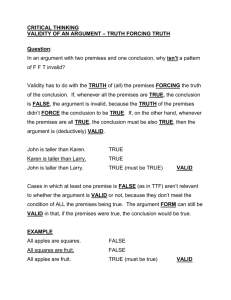

Philosophy 1100 Title: Critical Reasoning Instructor: Paul Dickey E-mail Address: pdickey2@mccneb.edu Website:http://mockingbird.creighton.edu/NCW/dickey.htm Today: Editorial Essay #1 Due. Next class: Midterm Exam Chapters 1-3 Homework: AT LEAST TWO HOURS ON QUIA ACTIVITIES !!! 1 Chapter Two, cont. Two Kinds of Reasoning How Do Premises Support Conclusions? For an Deductive argument, premises prove or demonstrate a conclusion based on if the premises make the conclusion certainly true. Consider the argument: (P1) If it’s raining outside, the grass near the house gets wet. (P2) It’s raining outside. _________________________ The grass near the house is wet. In a Deductive argument, premises prove a conclusion based on the logical form of the statement or based on definitions. It would be a contradiction to suggest that the conclusion is false but the premises are true. What is Logical Form? Consider the following argument: A good God cannot exist. There is evil in the world and any God who is good would not permit evil to exist. This argument can be stated as follows: (Premise 1) There is evil in the world. (P2) A God who is good would not permit evil to exist. ____ (Conclusion) A God who is good does not exist. What is Logical Form? Note that we can symbolize this argument with variables. In this case, say for example, this argument could be represented as: G = A good God exists, E= There is no evil in the world. This argument is of the form: If G E ~E _____ ~G Thus, it is a valid deductive argument. This is the deductive rule of Modus Tollens. EVERY argument that can be represented in this form is valid, regardless what G and E represent. How Do Premises Support Conclusions? For an Inductive argument, premises support (never prove) a conclusion based on how strongly the premises provide evidence for the conclusion. Consider the argument (Variation One): (P1) When it rains outside, the grass near the house only gets wet when the wind is blowing strongly from the North. (P2) The wind usually blows from the South in Omaha. ________________________ Even though it is raining, the grass near the house is not wet. How Do Premises Support Conclusions? For an Inductive argument, premises support (never prove) a conclusion based on how strongly the premises provide evidence for the conclusion. Consider the argument (Variation Two): (P1) When it rains outside, the grass near the house always gets wet when the wind is blowing strongly from the North. (P2) In Omaha, the wind usually blows from the South. (P3) Today the wind is blowing from the North. ________________________ The grass near the house is wet. How Do Premises Support Factual vs. Normative Conclusions? In regard to evaluating Inductive support for Factual vs. Normative Conclusions, I would suggest the following two tips to keep in mind 1) Only Factual Premises support Factual Conclusions. That is, if the conclusion is factual (or descriptive), ALL premises must be factual. 2) A Normative Premise is always needed to support a Normative Conclusion. That is, if the conclusion is normative (or prescriptive), there must be at least one normative premise. Of course, there may or may not be factual premises! Chapter Three: Vagueness & Ambiguity 9 Vagueness • A vague statement is one whose meaning is imprecise or lacks appropriate or relevant detail. “Your instructor wants everyone to be successful in this class.” “Your instructor is bald.” • Vagueness is often evident when there are borderline cases. Problem is not so much what the concept is but what is the scope of the concept. (e.g. baldness) • Some assertions may be so vague that they are essentially meaningless (e.g. “This country is morally bankrupt,” but most concepts though vague can still be useful. 10 Vagueness • A critical thinker will first want to clarify what is being asserted, even before asking about what are the reasons to believe or what is the evidence. • The more precise or less vague a statement is the more relevant information it gives us. a. Rooney served the church his entire life. b. Rooney has taught Sunday School in the church for thirty years. a. The glass is half full with soda pop. b. I poured half of a 12 oz can of soda pop into the empty glass. 11 Vagueness • What detail is appropriate depends on audience or the issue. It can be difficult to determine. Compare your friend calling you after reading an article in the paper about mortgage rates and telling you that you should expect to pay higher rates vs. your bank calling you and telling you that your mortgage rate is going up. You are at your neighbor’s for a BBQ and you ask him, “So how big is your yard? How far does the property line go to? “ He says “Oh, right behind the trees.” This is probably a good answer. But now you are thinking about buying his home and you ask the real estate agent the same question. You will not be satisfied with his “vague” answer. 12 Vagueness • Vagueness at times is intentional and useful. 1) Precise information is unavailable and any information is valuable. “This word just in. There has been a shooting at the Westroads Mall and there may be fatalities. More information will be forthcoming as soon as available.” 2) Precise information will serve no useful function in the context (yes, even in a logical argument!) Rarely, if ever, at a funeral, does a minister remind the grieving family that their father only attended church infrequently and showed no interest in his family attending. Ministers who would do such a thing would probably be considered jerks. 13 Vagueness in a Logical Argument • The bottom line in the context of analyzing or proposing a logical argument, a claim is vague when additional information is required to determine whether or not a premise is relevant. • Such vagueness is always a weakness and effort must be taken to avoid it. It is generally considered to be “hiding the evidence” when it is done intentionally. • You remove vagueness by adding the relevant detail. 14 Ambiguity • A statement which can have multiple interpretations or meanings is ambiguous. • Examples: “Lindsay Lohan is not pleased with our textbook.” “The average student at Metro is under 35.” “Jessica rents her house.” “Alice cashed the check.” “The boys chased the girls. They were giggling.” 15 Ambiguity • Of course, ambiguities can be obvious (and perhaps rather silly) “The Raider tackle threw a block at the Giants linebacker.” “Charles drew his gun.” • In these cases, we are not likely to be confused. The context tells us more or less what is meant. However, it should be understood that it is often not good to assume our audience will always have the same knowledge, orientation, and background that we do. 16 Ambiguity • Carmen's Swimsuit Switcheroo Frequently a logical argument is sabotaged by a person switching meanings in the middle of an argument. This is known as equivocation. We all know what we mean by “subjective” in this class, but we need to be sure that the term is used consistently and not switch to one of the other meanings in the middle of a a discussion. 17 Ambiguity • • Ambiguities can also be quite subtle, e.g. “We heard that he informed you of what he said in his letter.” • One ambiguity here is whether the person (the “you” in question) received a letter at all. Did “he” inform “you” of what he said but only we saw a letter to that affect, thus “we heard in his letter (to us),” or did “we hear” that within a letter “you” were informed and we heard that you were informed by means of a letter to “you”? • Such a point might seem tedious, but could in fact legally be very significant. Actually, Bill Clinton had a point when he said “It depends on what the meaning of is is.” e.g. Are you having a fight with your husband? 18 Ambiguity • Keep in mind that ambiguity, like vagueness, is at times intentional and often is useful. 1) Clever uses of “double meaning” can catch our attention and entertain us or provoke us to consider the claim more carefully. “Tuxedos cut ridiculously.” “You can’t pick a better juice than Tropicana.”’ “Don’t freeze your can at the game.” “We promise nothing.” 19 Ambiguity in a Logical Argument • The bottom line is that in the context of analyzing or proposing a logical argument, ambiguity is always a weakness and effort should be taken to avoid it. • If you use it for “effect,” you should be absolutely sure that the claim and your premises are clear to your audience. 20 Ambiguity • Please note that while with the case of vagueness, we resolved it by adding information that clarified meaning, with the case of ambiguity what we are interested in is to eliminate the suggestion of the potential alternate meaning that we do not desire. • “The Raider tackle threw a block at the Giants linebacker.” We want to eliminate the possibility that one could think that one is “throwing a block (of wood?)” Thus, we can say “ The Raider tackle blocked the Giant’s linebacker.” 21 Ambiguity • Let’s discuss three kinds of ambiguity. 1. Semantic ambiguity is where there is an ambiguous word or phrase, e.g. “average” price. -- When Barry Goldwater ran for president, his slogan was, "In your heart, you know he's right." In what way is this ambiguous? 2. Syntactic ambiguity is where there is ambiguity because of grammar or sentence structure, e.g. --“Players with beginners’ skills only may use Court #1.” 3. Grouping ambiguity is ambiguous in that the claim could be about an individual in the group or the group entirely, -- Baseball players make more money that computer programmers.” (fallacy of division) 22 Defining Your Terms • Defining terms helps one avoid vagueness and ambiguity. Video • Sometimes you need to use a stipulating definition if perhaps you are using a word in an argument in a different way than it is usually understood or it is a word in which there is itself some controversy. • It is frequently quite reasonable in a logical argument to accept a stipulating definition that you would not yourself have chosen, but does not pre-judge the issue and allows the discussion to precede without distractions. 23 Defining Your Terms • Most definitions are one of three kinds: 1. 2. 3. Definition by example. Definition by synonym. Analytical definition. • Any of these might be appropriate. • Be careful of “rhetorical” definitions that use emotionally tinged words to pre-judge an issue. • Do not allow someone in an argument to use a “rhetorical definition” as a stipulative definition. If you do, the argument will likely be pointless and subjective. 24