Growing up in Foster Care - International Society for Child Indicators

advertisement

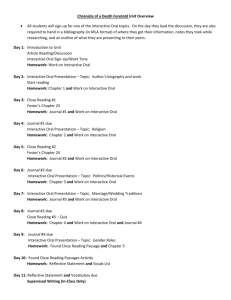

GROWING UP IN FOSTER CARE PERCEPTIONS OF CHILDREN’S WELLBEING Associate Professor Elizabeth Fernandez Social Work School of Social Sciences and International Studies University of New South Wales 26th – 29th July 2011 University of York 3rd Conference of the International Society for Child Indicators e.fernandez@unsw.edu.au The impact of the care experience on children’s wellbeing • Children come to the foster family setting as an already at risk group in relation to children's wellbeing in care research has identified a range of concerns including • Instability in care placements (Barber & Delfabbro, 2003; Fernandez, 1999; Pecora, Williams, Kesler & Herings, 2003; Ryan and Testa, 2004) • Inability of care systems to ensure optimal educational outcomes (Jackson, 2000; Dobel-Ober, Lawrence, Berridge & Sinclair, 2003; Rosenfeld & Richman, 2003; Zetlin, Weinberg & Kimm, 2003) • Children’s vulnerability to physical and emotional difficulties while in care ( Flynn, Ghazal, Legault, Vandermeulen & Petrick, 2004; James, Landsverk, Slymen & Leslie, 2004 • Risk of losing attachments to their biological families (Cleaver, 2000; Kufeldt et al, 2003) 2 The impact of the care experience on children’s wellbeing • Current research points to limitations of cross sectional studies in capturing developmental sequences • Limited research that views outcome from different participants in the foster care process (Courtney, 2000; Kelly & Gilligan, 2002) • Increasing recognition of the need to give a central place to the voices of children in research and practice (Gilligan, 2002; Newman, 2003) 3 The Research Aims • To document the needs and experiences of children in care from the perspective of their carers, case workers, birth parents and children themselves • To explore children’s perceptions of their developing relationships with foster families, and their established relationships with their birth family and significant others • To analyse the perceived adjustment and psychosocial functioning of children over the study period and document placement and developmental outcomes 4 Data Collection • Interviews were carried out at 4 months after entry to care and 18-24 month intervals thereafter • Child interviews (8 – 18 yrs) • Caseworkers (of children of all ages) • Foster/adoptive carers (of children of all ages) • Birth parents (of children of all ages) 5 Data Collection (cont’d) Measures used in the study • Achenbach CBCL (completed by carers) • Achenbach TRF (completed by teachers) • Hare self esteem scale (completed by children) • Interpersonal parent and peer attachment scale (completed by children) • Attachment styles questionnaire (completed by carers) • Foster care alliance scale (completed by children and carers) 6 About the Children • 59 children participated in the study • Boys 52% • Girls 48% • Ages ranged from 3 to 15 • Children are from Barnardos Find-a-Family Program, an integrated service of permanent family care and adoption for “hard to place” children requiring longterm placement. Many have multiple failed placements prior to their Find-a-Family placement 7 Care History • Total placements – A third of the children had more than 5 placements in total including pre Barnardos care history – The median number of placements was 4 placements and the average was 4.3 placements – The majority (71%) of respondents are in non relative foster families and a further 19% are adopted – Half the children have been in their current placement for four years or more 8 Children’s Conceptions of Fostering • What is a foster home?: "Places of refuge where people can stay, where you get looked after.” Would you call this home a foster home?: "No, this is my house.” (male, 11 years) • “A person who acts like your mum and dad, I haven’t got my mum and dad or my brother or the pets that I had before. That’s why it’s not the same. You’re in somebody else’s house and it’s not your real mum and dad but it’s the person that’s looking after you for the moment.” (female, 8 years) • “Um, I think it is alright. It is not that much different than living with a real parent. You still have your real parents but you have another family that supports you. That help you, they do what your real parents do, because they cant for whatever reason” (female, 13 years) • “No a normal kid like everyone else. Because here it is like a real family. Some parents don’t care about children, that’s why I came into foster care.” (male, 12 years) 9 Children’s Conceptions of Fostering (cont’d) • “The good things umm. I guess the good thing is like feeling you are part of the family but the bad thing is knowing that they are not you family, you know” (female 15 years) • “For me it’s good, for me I like it cause I’ve got good parents and good friends and I’m just lucky” (female,14 years • “Sort of because they miss their mum and they really want to go back to her, and they won’t be able to see her for a long, long time, so they act differently because of this. But once they settle in they get fine, and then um they just forget about it and start moving on.” (male, 9 years) • “I don’t know. I don’t really know what its like to be a foster adult. I don’t really know what its like to be a normal child” (male, 17 years) 10 Change of Placement and Children’s Responses Many of the children interviewed had multiple carers over time. Children’s placements ranged from 2 to 7 foster homes. Many children were aware that they would eventually find a permanent foster placement, even though they were not sure how long their present placement would last • “(SIGH) well if I am very very, extremely good I might stay here and this might be my forever family but if um, if this isn’t a good place I will have to move, which I don’t want to” (female, 8 years) • “(Until) I'm old enough to move out into a flat” (female, 11years) • “Hard to make friends, and hard to keep contact with my old friends” (female, 14 years) • “I feel sad at times, leaving my friends behind and moving to different schools, trying to make new friends” (male, 16 years) 11 Foster Parent Cohesion • Forty-eight per cent of respondents indicated they got on 'very well' both with their foster mother and their foster father. • All but one respondent indicated that they got on with their foster mother ‘very well’ or ‘quite well’ • Almost 9 out of 10 respondents were positive about their relationship with their foster father, rating 'very well' or 'quite well‘ • Eighty-six per cent of respondents were positive about their relationship with their foster sibling • The relationships with the foster mothers remained very positive, especially amongst boys and younger children • Children who had a stronger level of maternal attachment were more likely to sustain highly cohesive relationships within the foster families 12 Children’s perceptions of cohesion • The higher the cohesion with the foster mother the higher the cohesion with the foster father (r=0.37, n=40, p=0.021) • Age was significantly related to cohesion with the foster father (r=0.5, p=0.01) such that older children were less likely to report getting on “very well” with the foster father • The child’s cohesion with other children from the foster family, was significantly related to the child’s number of placements • Children who got on very well with the children of the foster family had significantly fewer placements than children who did not get on very well (p= 0.018) 13 Cohesion with Foster Mother – Foster Father In general the children manage to have good relationships with their carers. Q. “What is it like living here, with (Carer)” • “She is the best mum, and she looks after me and she takes me to school. He is the best dad and he works for my family to get money, so does mum and they make us live more” (male, 11 years) • “They cuddle me and they say that they love me, they take care of me all the time. They take me to the doctors if I look sick. They give me food on a plate. They give me my room, my own room. They take me to friend’s houses and drop me off at school and pick me up and they say that they love me” (male, 11 years) • “Good, everything is good. I want to stay here until I have money to buy a house.” (male, 10 years) 14 The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) • The IPPA, was administered at Interviews 2 and 3 to assess each child’s level of attachment to his or her current foster mother, foster father and friends or peers. • There are three subscales – trust, communication and alienation and a total attachment score • A higher score indicates greater attachment • T-tests were used to compare the each child’s scores at these two interviews on the IPPA three subscales – trust, communication and alienation and a total attachment score. • The analyses indicated statistically significant changes in the children’s ratings for maternal and peer attachment but not for paternal attachment 15 Changes in IPPA scores from Interview 2 to Interview 3 for all children Interview 2 Interview 3 Mean Std Dev Mean Std Dev sig Alienation 22.5 3.4 25.8 3.4 p=0.001 Communication 23.1 3.5 23.9 4.3 ns Trust 28.2 4.0 33.2 5.0 p=0.000 Total 91.2 12.6 102.7 15.8 p=0.008 Alienation 23.0 3.6 23.66 5.4 ns Communication 23.3 3.0 22.7 5.9 ns Trust 28.5 4.3 31.0 6.9 ns Total 91.3 12.4 95.3 22.4 ns Alienation 22.1 4.7 24.0 5.2 ns Trust 33.5 6.1 37.6 6.1 p=0.023 Communication 27.0 5.0 31.3 5.8 p=0.002 Total 85.7 15.7 96.7 15.4 Maternal Attachment Paternal Attachment Peer Attachment p=0.013 16 The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) (cont) • Children reported better maternal attachment trust and communication, and overall peer attachment • Indicates that the children are feeling more settled in their relationships with their foster mother and the same aged children • No progression or deterioration in the children’s feelings of attachment toward their foster father • Boys reported improved scores on three maternal attachment scores, including alienation, trust and the total score. They also showed and significantly improved scores on all the peer attachment scores • Younger children had stronger maternal trust and better peer communication at Interview 3 17 The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) (cont) • The teenage children had improved maternal alienation scores, better maternal trust and improved total maternal attachment scores. Additionally older children had significantly better peer communication scores. There were no changes in paternal attachment scores • The changes were in a positive direction and not signalling deterioration and lend some support to the benefits of the children’s time in care • Most encouragingly the strongest changes were observed for boys and for older children • Older children and boys were “catching up” to the girls and younger children on some of these variables 18 Relationships between IPPA subscales • Children’s responses to the maternal and peer subscales are closely inter-related • Responses to the Paternal Attachment questions, however were only related to each other and not to the other two sets of subscales • Children’s attachment to their peers and foster mothers were based on similar judgements but children thought in a different way when considering their attachment to their foster fathers 19 Frequency of Contact • Birth Mothers and siblings were the most frequently contacted family members • One child in 5 had contact with his or her birth mother at least monthly • Nearly three-quarters of children (72%) saw their birth mother at least once every 3 months • A quarter had no contact at all • Just over half (56%) of the children had no contact at all with their birth father • 28% saw their father between once a month and every few months or holidays 20 Frequency of Contact (cont) • Grandparents were an occasional point of contact • 26% of children confirmed contact with their maternal aunt • 4 children in 10 had ongoing contact with their previous carers • Nine in ten (90%) respondents report that since the last interview they have had some contact with their siblings who are not living with them. One in four had contact either monthly or fortnightly with them 21 Children’s Connection with their Birth Parents ‘…they say that she's not a proper Mum’. (male, 11yrs) Children throughout the interviews seem very connected to their birth mother. The children in the main have a desire to live with their mothers or would choose to confide in their birth mother if they were having any difficulties, although the foster mothers were also noted as a confidante. • “That she is still alive and I can talk to her. I have questions that want answers and sometimes we argue. It’s all over again, feel sad for my mum, and when its time to depart. I re-live past a little” (female, 18 year) • “Sometimes but most of the time not really.. It’s hard that you have two families and you only get to see each family some of the time. And you don’t know which to call mum, and they don’t know which mum you are talking about and it’s hard” (female, 12 years) Some children expressed clear and positive connections with their birth parents while also evaluating the positive aspects of the new home. • “I want to live with my mum but I like the school and that ...And mum couldn't pay for the school, so I'll live here, but I probably want to live with my mum” (male, 12 years) 22 Current Contact with Family of Origin (cont) • Compared to Interview 1, the significant change was an increase in children’s desire to see their fathers • Many of the children expressed that they never see their birth fathers, they did however appear to be interested in seeing them and establishing a connection • ‘…I'd like to see him (father) a lot more, heaps and heaps and heaps more times, it makes me feel happy’ (female, 8years) • ‘I don’t have a real dad, I never did. I only have false dads’ (female, 8 years) • ‘I’ve never had a first dad’ (male, 11years) • “Sometimes I do, I want to know about my dad because I don’t know where he is from. People ask me where he is from and I just have to say I don’t know. They say what do you mean you don’t know? And imp like ‘I don’t know’” (female, 16 years) 23 Children’s Interviews • Children’s self esteem was assessed using the hare self esteem scale. Includes peer self-esteem, home self esteem and school self-esteem and a total score • Girls and boys both had an average of 82 • Peer self esteem was negatively correlated with total number of placements, (r= -0.42, p=0.05) so that the more placements children had the lower their peer self esteem • Age at entry to care was also found to be related to “global self esteem” (r=0.37, p=0.05). That is, children who went into care at an older age had higher self esteem at interview 2 24 Hare Self Esteem Scores, including gender breakdown • Girls were found to have remained stable from Interview 2 to Interview 3 on all the subscales and the total self esteem score • Boys however had significantly higher home self esteem scores and total self esteem scores at Interview 3 compared to interview 2 • This finding is encouraging given the small sample sizes and indicates that boys responded positively to the foster home environment 25 Self esteem and Children’s care history From the children’s interviews it was apparent that being in care affected their self esteem. However, the children did also compare themselves to their peers for some reassurance • “It’s like we're second hand kids; unless that's how all kids feel who are my age…” (female, 12 years) • “When I see my friends with their parents I see nothing different...it just seems the same, like I’ve got play stations and Nintendo’s, and being allowed to play and going to friends houses as well” (male, 13years) • “Some people in my class don't even have a dad. And I get lots of stuff”(female, 10years) 26 Child Behaviour Checklist • In the present study the CBCL 4-18 was used • This is an observational measure for children aged 4 to 18 (Achenbach 1991) which assesses 113 problem behaviours to provide information on 3 overall problem scores • Internalising Problems: inhibited or over-controlled behaviour (I, II and III) • Externalising Problems: antisocial or undercontrolled behaviour e.g., delinquency or aggression (IV and V) • Total Problems Scale: all mental health problems reported by parents or adolescents • 8 further subscales 27 Children aged 4-17 years in “clinical range” of problems on CBCL, compared to the Mental Health of Young People in Australia (MHYPA) Survey (n=3870) 2nd Initial Interview Interview Summary scales MYPHA % % % Total problems 38.2 43.4 14.1 Internalising problems 21.8 35.8 12.8 Externalising problems 37.3 34.0 12.9 Comparisons are made with the findings of the Australian government’s mental health of young people in Australia (2000), based on a national representative sample 28 Carer Ratings on the Achenbach Child Behaviour Checklist interview 1 • 43.4% of the children were in the clinical range for number of total problems • 35.8% for internalising problems • 34.0% for externalising problems • Clinical rate for “Total Problems” is three times the Australian community sample • Internalising and externalising problems exceeded the MHYPA community norms 29 Carer Ratings on the Achenbach Child Behaviour Checklist interview 2 • Between 7.5 and 28% demonstrated clinically significant problems on the subscales • Attention problems, social problems, delinquent behaviour, anxiety and depression rated in the clinical range • 38% of children were in the clinical range of “total problems” • 22% for internalising problems • 37% for externalising problems 30 Comparison data of scores from Interviews 1 to 2 • Significant decreases detected between carer ratings at Interview 1 and 2 on the internalising scores (t=2.07, df 50, p<0.05) and the anxiety and depression subscale (t=2.01, df 50, p< 0.05) • Fewer children fell into the clinical range of “total problems” at the second interview • Ratings remained above the Australian normative data on all subscales total problems and externalising problems • Internalising problems had dropped. 31 CBCL Teacher Report Form (TRF) • Teachers of children in care were asked to complete the Achenbach teachers check-list, a companion to the child behaviour checklist • The instrument is norm referenced and assesses key problem sub-scales and overall problem scores • The TRF also includes an Adaptive Functioning Scale which include 5 ratings over two subscales on the child’s positive attributes as displayed at School 32 TRF (cont’d) • Academic Performance – teacher’s ratings of the child’s performance in academic subjects • Adaptive Functioning • Four adaptive characteristics and the sum of the four characteristics – How hard the child is working – How appropriately he/she is behaving – How much he/she is learning – How happy he/she is • The TRF was completed for children aged between 5 and 17, with an average age of 11.1 years (sd 3.1 years) • Additionally each child’s main teacher completed a checklist for another child in the class, matched for age and sex but who resides in a birth family 33 Table: T-scores for TRF Problems at Assessment 1 for Care and Control Groups Care Group mean Control Group sd max mean sd max internalising problems 53.35 8.67 80.00 56.37 8.48 68.00 externalising problems 56.72 9.19 84.00 52.14 7.51 66.00 total problems 56.40 8.95 80.00 55.09 7.34 68.00 34 Table: (cont’d) Care Group Control Group Subscales mean sd max mean sd max aggressive behaviour 58.21 8.22 91.00 54.28 4.77 66.00 anxiety/depression 56.81 6.24 77.00 59.09 7.23 71.00 attention problems 57.47 5.91 73.00 56.33 5.12 68.00 delinquent behaviour 56.35 6.98 78.00 54.16 4.94 69.00 social problems 58.63 7.49 81.00 56.53 6.02 70.00 somatic complaints 52.56 5.79 77.00 51.21 2.99 64.00 thought problems 54.63 6.98 78.00 52.42 6.88 83.00 withdrawn 53.91 4.87 67.00 55.95 5.48 70.00 35 Children in care • The problem subscale scores have a minimum of 50, and a clinical cut off of 64 • The maximum scores for the children varied from 67 (withdrawn) to 91 (for aggressive behaviour) • The average scores ranged from 52.6 (somatic complaints) to 58.63 (social problems) • the highest average scores for girls was social problems (mean 59.65) and for boys, aggression (mean 58.48) • There were 14% children in the clinical range for the summary scores for internalising problems, (greater than 63 on the teacher ratings), 21% with externalising problems and 17%7 over threshold on “total problems” 36 Control Group Children • Compared to the children in care only two significant differences were detected • Firstly the children in care had higher t-scores on aggressive behaviour (means = 58.2 for care and 54.3 control; P=0.013) • The care group had higher t-scores for externalising problems (means =56.7 for care, 52.1 for control, p=0.019) • The control group had high level of children in the clinical range of scores for internalising problems • 25%of the children in the control group had scores which fell in the clinical range for internalising problems 37 Table: T-scores for adaptive functioning scales for children in care and control group Care Children Control Children mean sd max mean sd max Academic Performance 43.60 6.22 60.0 45.69 6.47 65.00 Working Hard 45.63 5.98 59.0 46.36 6.09 65.00 Behaving Appropriately 42.86 5.93 57.0 45.64 5.59 60.00 Learning 43.49 6.63 65.0 44.07 6.72 65.00 Happy 45.30 5.40 59.0 45.62 4.99 58.00 Sum working hard to happy 43.16 6.02 59.0 44.36 6.29 64.00 A high score is indicative of more adaptive functioning 38 Adaptive Functioning Scales (TRF) • Children in care – children in care had the highest average score for “happiness” and the lowest for behaving appropriately – By gender, girls had their highest average ratings for working hard (mean = 44.85) – and the boys, being happy (46.35) or working hard (46.5) – The highest percentiles in the scales for this group ranged from 73rd percentile (behaving appropriately) to the 93rd percentile (learning) • Control group – The control group children’s percentile means varied from a low of 30.31 for learning, to a high of 37.40 for working hard 39 Comparisons between the groups at assessment 2 • Both groups demonstrated significant changes in their TRF problem scores from the first assessments • With regard to the summary scales, both groups showed significant reductions in the ratings • In the subscales, the care group changed in six areas, as opposed to 4 areas in the control group • The strongest changes for the control group surrounded the internalising cluster • The care children showed most change in the externalising clusters 40 Summary • Both the children in care and control group had a range of problems detected • Evidence of a greater prevalence of problems in the care group • The high prevalence of internalising problems amongst the control group • At the second assessment there were no differences between the two groups on the problem subscales, which, in a restorative program is a positive finding 41 Summary (cont’d) • On the adaptive functioning scales, children in care showed significant improvements across all subscales • Children in care were functioning near to the 50th percentile, based on the normal population • Control group showed some significant gains but without the same breadth or magnitude • Some of this change may be attributed to the effects of restorative care and the Barnardos intervention 42 Caseworker Assessments Of Child’s Adjustment (cont) • Caseworkers were asked to rate the child’s adjustment on a 4-point scale where 1= ‘poor’ and 4= ‘excellent’ • Caseworkers rated 84% of children’s adjustment as ‘excellent’ (40%) or ‘adequate’ (44%) • ‘mixed’ (10%) or ‘poor’ (6%) adjustment • Younger children were rated as having better adjustment than older children [t(34)=3.3, p=0.002] 43 Adjustment to placement over time • The proportion of children in placement with excellent adjustment grows with time • 17.5% to 58.5% in year 3 • 54.5% in year 4 • Mixed or poor adjustment decreases from 42.5% in year 1 to 16% in year 6 44 Caseworkers ratings of child’s academic progress • Caseworkers were asked to rate the child’s academic progress over the last 2 years. Three-quarters (75%) were rated as progressing very well (19%) or moderately well (55%). Approximately a quarter (26%) of children were rated as progressing ‘not very well’. There were no age or sex differences • Those children who have been with their carers for at least 3 years have, on average, better academic adjustment and better overall adjustment [t(45)=-3.56, p=0.001] • And better health [t(44)=1.98, p=0.054] 45 Change of Schools Three quarters of the children had experienced at least one change in schooling since their separation from their birth family More than half of the children had had three or more changes • “Heaps, probably about 5 or 6 times. I think I get stupider every time I have to move” (female,14 yrs) • “I’ve been to thousands of schools...about, 5 or 6. I don't know” (male, 11years) When asked to evaluate how they were doing at school, most children attempted to assess their own abilities. • “…can't hardly read…and plus I'm year 5 going in year 6…can't even hardly read or do neat writing…’ (female, 10 years) • “Um, playing and English. I'm not so good at my maths” (female, 11years) • “Hand writing everything. Not everything in the world though…I'm good at mostly everything” (female, 8yrs) • “Um I was going really well in school and the whole time I was in the top of classes. I enjoyed it and wish I had finished” (female, 19 years) 46 Positive life events Per cent ‘Yes’ Per cent ‘Yes’ Achievements Educational achievements Sports or athletic achievements Other recreational activities (eg music/ art) Trips, vacations Having a pet Attachment Bond with birth parent 52 48 44 76 48 32 Bond with previous caregiver 8 Bond with present caregiver 72 Significant Other attachment Visiting siblings, birth parents, extended family Friendships 30 50 62 Stable foster placement Stable foster placement 78 Job/ Culture 14 Job/ employment Other Developmental achievements Participation in significant family events Move to emotionally healthier environment Better health Healing (emotional, psychological) 52 65 33 18 29 47 Positive life events • 94% of children had at least one of the five listed ‘achievement’ life events • 48% had had two or three such events • 92% of children had at least one of the six listed ‘attachment’ life events • 52% had had two or three such events • Caseworkers rated 90% of children as being in ‘excellent’ (41%) or ‘very good’ (49%) health 48 Positive Achievements and Critical Events • Most frequently reported was having a stable foster placement (78%) • Three quarters of the children (76%) were able to go on a trip or vacation • Development of relationships with carers, new friends or birth family was also common, experienced by two thirds • Many children experienced some level of educational achievement (52%) or sporting achievement (42%) • The most frequently reported critical or crisis events reported included the experiences of bullying, emotional abuse and violence or physical abuse 49 Positive life events • The greater the total number of positive life events the better the academic adjustment (r=0.42, p=0.003), health (r=0.38, p=0.007), and the better the caseworker’s overall adjustment assessment for the child (r=0.34, p=0.016) • The greater the positive achievement life events the greater the academic adjustment (r=0.58, p<0.001), health (r=0.43, p=0.002) and overall adjustment ratings (r=0.38, p=0.008) • The greater the number of positive attachment life events the greater the health assessment (r=0.38, p=0.008) • Having a stable foster placement is related to higher academic adjustment t(44)=-3.50, p=0.001), higher satisfaction with the placement t(48)=-3.20, p=0.002), health; t(47)=-4.94, p<0.001), and higher adjustment scores 50 Parenting Variables • Caseworkers were asked to rate carers on a number of variables relating to parenting styles and skills • ‘the ability in relation to managing the child’ and disciplinary style were the more problematic areas noted • Those with a younger child were more likely to be rated as never having a problem with disciplinary style or level of aggression in parenting (81%) than were those with an older child (38%) 51 Caseworkers’ Assessments of Parenting Styles Responsiveness Rating Ability to Ability to Ability in Disciplinary express respond relation to style/ level of warmth sensitively managing aggression child Never a problem % % % % % 66 77 80 47 59 34 23 20 53 42 100 100 100 100 100 Problem developed or resolved Total 52 Parenting Variables Responsiveness • Problems with the carer’s responsiveness was negatively related to the child’s academic adjustment (=-0.49, p=0.001) • The caseworker’s overall satisfaction with the placement (=-0.47, p=0.001) • The child’s overall adjustment (=-0.65, p<0.001) • And health (=-0.48, p=0.001) Warmth • Problems with the carer’s ability to express warmth towards the child was negatively related to the caseworker’s overall satisfaction with the placement (=-0.50, p<0.001) • the child’s overall adjustment (=-0.55, p<0.001) • And health (=-0.40, p=0.005). There was no association with the child’s ease of making friends or academic progress Sensitivity • Problems with the carer’s ability to respond sensitively was negatively related to the child’s academic adjustment (=-0.33, p=0.023) • The caseworker’s overall satisfaction with the placement (=-0.59, p<0.001), the overall adjustment (=-0.64, p<0.001) 53 • The child’s health (=-0.44, p=0.002) Parenting Variables (cont) Ability to manage child • The carer’s ability in relation to managing the child was negatively related to the caseworker’s overall satisfaction with the placement (=-0.30, p=032) • The child’s overall adjustment (=-0.39, p=0.006) • And health (=-0.35, p=0.014) Disciplinary Style / Level of Aggression • The carer’s disciplinary style or level of aggression in parenting was negatively related to the child’s academic adjustment (=-0.35, p=0.015) • The caseworker’s overall satisfaction with the placement (=-0.45, p=0.001) • Overall adjustment (=-0.62, p<0.001) • And health (=-0.59, p<0.001) Stressors on Carers • Rating of the child’s overall adjustment is higher on average in the absence of a stressor on carers that is related to the care of the child (t(47)=-2.26, p=0.029) 54 Summary and Implications • Children had high levels of psychological need • Children’s scores on the CBCL were higher than published normative data reaffirming their level of psychological need findings from this and previous research. • Problems with attention, social interactions, anxiety, aggression approximate estimates from other studies • Findings underline the importance of recognising emotional and behavioural difficulties experienced by children in care early and identifying their impact on carers. • A comprehensive plan of placement support for carers including specialist assessments and access to treatment services and stress management is indicated and lower case loads. • Monitor children at increased risk of instability in care • Support children at risk of psychological difficulties with therapeutic services • Support carers in enhancing their relationship with troubled children • Skill foster parents in approaches needed for the sensitive management of children’s emotional and behavioural problems 55 Summary and Implications cont’d • Children reported good levels of cohesion with foster carers at 3 interviews. Significant relationships emerged regarding the children’s judgment of their interpersonal skills and attachment with their foster parents • Resources and training to enable carers and care systems to build on these strengths is stressed • The nature of the relationship with the foster fathers appear to have had an important developmental influence on the children. Developing approaches to promote fuller involvement of fathers in fostering relationships are important to outcomes for children • While acknowledging strong attachments with their foster parents children desired more contact with their family of origin. • Contact remains a challenging and contentious issue (Cleaver, 2000) and carers must be supported in their dual task of building strong attachments with their foster children while responding to the children’s need for continuing connection with birth families 56 Summary and Implications cont’d • Children’s sense of happiness improved overtime is a positive finding implying placement in care provided a route to rehabilitative intervention for children with maltreating histories • Permanent care afforded a context to develop a more secure base • Being in care offered a pathway into restorative services • School environment and the educational process can potentially offer structure, boundaries and security to the children in care systems • Develop co-ordinated multidisciplinary response to address overlapping domains of need, such as education and mental health 57 Methodological and Ethical Considerations • Justification of children’s involvement and value in being ‘heard’ • Negotiation of informed consent- who gives consent and how • Role of gatekeepers in enabling/disabling consent/participation • Ensuring processes for disengaging and debriefing from interviews • Availability of care professionals for referral to deal with the emotional impact of interviews • Providing a safe and confidential environment to express their views • Confidentiality and limits arising from child protection legislation 58 Publication related to the study • Fernandez, E. (2010), Wellbeing in Foster care: An Australian Longitudinal Study of Outcomes in Fernandez, E., Barth, R. (Eds), ‘How Does Foster Care Work? International Evidence on Outcomes, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers • Fernandez, E. (2009), Children’s wellbeing in care: Evidence from a longitudinal study of outcomes, Children and Youth Services Review, vol. 31 • Fernandez, E. (2008), Unravelling Emotional, Behavioural and Educational Outcomes in a Longitudinal Study of Children in Foster Care, British Journal of Social Work, vol. 38, iss. 7, pp1283-1301 • Fernandez, E. (2007), How Children Experience Fostering Outcomes: Participatory Research with Children, Child and Family Social Work, vol. 12, iss. 4 , pp349-359 • Fernandez, E. (2006), Growing up in care: Resilience and care outcomes. Promoting resilience in child welfare. (Eds Flynn, R.J., Dudding, P.M, and Barber, J.G.) University of Ottawa Press. Ch. 8. (pp 131-156) 59