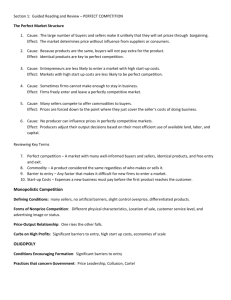

Chapter 12: Monopoly and Antitrust Policy

12.1

Ch. 12 Monopoly and Antitrust

In this chapter we study markets that are controlled by a single firm.

Some basics:

• An imperfectly competitive industry : single firms have some control over the price of their output.

• Market power is the imperfectly competitive firm’s ability to raise price without losing all demand for its product.

We define an industry/market with:

The ease with which consumers can substitute one product for another. Ease of substitution limits the extent to which a monopolist can exercise market power.

The more broadly a market is defined, the more difficult it becomes to find substitutes

Pure Monopoly

A pure monopoly is an industry with a single firm

• that produces a product for which there are no close substitutes

• significant barriers to entry prevent other firms from entering the industry to compete for profits.

Examples:

12.2

What are Barriers to Entry?

•

•

•

•

Things that prevent new firms from entering and competing in imperfectly competitive industries include:

Government franchises , or firms that become monopolies by virtue of a government directive.

Patents or barriers that grant the exclusive use of the patented product or process to the inventor.

Economies of scale and other cost advantages enjoyed by industries that have large capital requirements. A large initial investment, or the need to embark in an expensive advertising campaign, deter would-be entrants to the industry.

Ownership of a scarce factor of production: If production requires a particular input, and one firm owns the entire supply of that input, that firm will control the industry.

12.3

Firm Decision-Making: Price is the Fourth

Decision Variable

Firms with market power must decide:

1.

how much to produce

2.

3.

4.

how to produce it how much to demand in each input market what price to charge for their output.

To analyze monopoly behavior we assume that:

• Entry to the market is blocked

•

•

•

• Firms act to maximize profit

The pure monopolist buys in competitive input markets

The monopoly faces a known demand curve

The monopolistic firm cannot price discriminate

12.4

Price and Output Decisions in Pure Monopoly

Markets

12.5

There is no distinction between the firm and the industry. In a monopoly, the firm is the industry

The firm faces the entire market demand curve, and total quantity supplied in the market is what the firm decides to produce.

12.6

For a Pure Monopolist:

The monopolist faces a downward-sloping market demand curve; it is NOT perfectly elastic.

The monopolist cannot sell all that it wants to at a given price.

It can only sell what the consumers will buy at each possible price, as reflected by the market demand curve.

The monopolist’s objective is the same as that of the perfectly competitive firm: to choose the output level (Q*) that maximizes profits.

It will be where MR = MC.

Note : a choice of Q* implies a choice of Price (P*) because the monopolist must locate at a point on the demand curve.

Marginal Revenue Facing a Monopolist

For the monopolist, marginal revenue is not equivalent to price because the monopolist cannot sell all that it wants to at a particular price. To sell one more unit, the monopolist must lower price

12.7

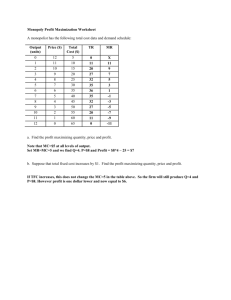

Marginal Revenue Facing a Monopolist

(1)

QUANTITY

0

(2)

PRICE

$11

(3)

TOTAL REVENUE

1

2

3

10

9

8

9

10

7

8

4

5

6

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

(4)

MARGINAL REVENUE

-

Marginal Revenue Curve

Facing a Monopolist

• For a monopolist to sell one more unit, it must lower the price on all units sold

At every level of output except one unit, a monopolist’s marginal revenue is below price. (MR < P)

12.8

12.9

Marginal Revenue and Total Revenue

• A monopolist’s marginal revenue curve shows the change in total revenue that results as a firm moves along the segment of the demand curve that lies exactly above it.

• For a linear demand curve, the MR curve will be twice as steep.

Price and Output Choice for a Profit-Maximizing

Monopolist

12.10

• A profit-maximizing monopolist will raise output as long as marginal revenue exceeds marginal cost (like any other firm). As the monopolist produces and sells more, MC ↑ and MR ↓.

• The profit-maximizing level of output is the one at which

MR = MC

The Absence of a Supply

Curve in Monopoly

A monopoly firm has no supply curve that is independent of the demand curve for its product.

• A monopolist sets both price and quantity, and the amount of output supplied depends on both its marginal cost curve and the demand curve that it faces.

12.11

Price and Output Choices for a Monopolist Suffering

Losses in the Short-Run

12.12

• It is possible for a profitmaximizing monopolist to suffer short-run losses.

• If the firm cannot generate enough revenue to cover total costs, it will go out of business in the long-run.

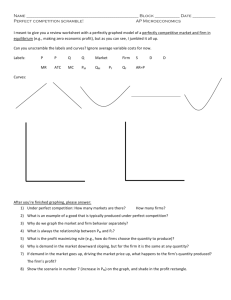

Remember Perfect Competition

Perfectly Competitive industry in the long-run, price will be equal to long-run average cost. The market supply is the sum of all the short-run marginal cost curves of the firms in the industry.

12.13

Perfect Competition and

Monopoly Compared

12.14

P m is the price a monopolist would set.

Q m is the quantity a monopolist would produce.

P c is the price a perfectly competitive market would set. Q c is the quantity a perfectly competitive market would produce.

P m

> P c and Q m

< Q c

• Relative to a competitively organized industry, a monopolist restricts output, charges higher prices, and earns positive profits.

• There is no long-run equilibrium in which profits are competed away through the entry of new firms.

Collusion and Monopoly Compared

Collusion is the act of firms working with other firms in an effort to limit competition and increase joint profits.

Examples:

12.15

When firms collude, the outcome would be exactly the same as the outcome of a monopoly in the industry.

12.16

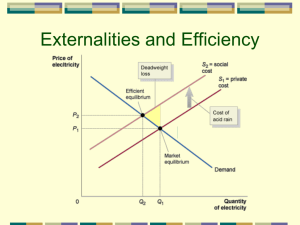

The Social Costs of Monopoly

Suppose a firm has no fixed costs and marginal cost is constant.

These assumptions simplify the cost diagram as shown below.

Monopoly leads to an inefficient mix of output

Price is above marginal cost

(P m

> MC), which means that the firm is underproducing from society’s point of view.

Perfect Competition is efficient

Price equals MC (P c

= MC), and the efficient quantity is being produced (Q c

)

12.17

The Social Costs of Monopoly

The triangle ABC measures the welfare loss (a.k.a. deadweight loss or social cost) from the market being monopolized.

This welfare loss or social cost is measured as a loss in consumer surplus from the market being monopolized.

12.18

Rent-Seeking Behavior

Sometimes the cost is even greater than the triangle:

Rent-seeking behavior refers to actions taken by households or firms to preserve positive economic profits.

A rational owner would be willing to pay any amount less than the entire rectangle P m

ACP c to prevent those positive profits from being eliminated as a result of entry.

12.19

Price Discrimination

No Price Discrimination Perfect Price Discrimination

A monopolist who cannot price discriminate would maximize profit by charging $4.

There is profit and consumer surplus.

For a perfectly price discriminating monopolist, the demand curve is the same as marginal revenue.

There is profit but no consumer surplus.

Remedies for Monopoly:

Antitrust Policy

12.20

• A trust is an arrangement in which shareholders of independent firms agree to give up their stock in exchange for trust certificates that entitle them to a share of the trust’s common profits. A group of trustees then operates the trust as a monopoly, controlling output and setting price.

• In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Act , which declared every contract or conspiracy to restrain trade among states or nations illegal; and any attempt at monopoly, successful or not, a misdemeanor.

• The Clayton Act , passed by Congress in 1914, strengthened the Sherman

Act and clarified the rule of reason. The act outlawed specific monopolistic behaviors such as tying contracts, price discrimination, and unlimited mergers.

12.21

The Enforcement of Antitrust Law

• The Antirust Division (of the Department of Justice) is one of two federal agencies empowered to act against those in violation of antitrust laws. It initiates action against those who violate antitrust laws and decides which cases to prosecute and against whom to bring criminal charges.

• The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), created by Congress in 1914, was established to investigate the structure and behavior of firms engaging in interstate commerce, to determine what constitutes unlawful “unfair” behavior , and to issue cease-and-desist orders to those found in violation of antitrust law.

Natural Monopoly

A natural monopoly is an industry that realizes such large economies of scale in producing its product that single-firm production of that good or service is most efficient

In this situation, we don’t want to use Antitrust laws to prevent monopoly. Instead, one firm is allowed to supply the market, but the government regulates its behavior so that it doesn’t act like a monopolist.

This is generally done by restricting the prices the monopolist can charge and preventing it to restrict output.

12.22

P m

12.23

Natural Monopoly

Assume constant marginal cost and high fixed costs

ATC is falling over the relevant Demand range. Only one firm is needed to supply the market.

P c

Q m

MR

Demand

ATC

MC

Q c