Building Econometric Models

advertisement

Capitulo 5

Modelagem e Previsão de Series

Temporais Univariadas

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

1

Modelos de Series Temporais

• Onde tentamos prever retornos usando somente informação contida nos seus

valores passados.

Alguma Notação e Conceitos

• Um Processo Estritamente Estacionario

Um processo estritamente estacionario é um onde

P{yt1 b1,..., ytn bn} P{yt1 m b1,..., ytn m bn}

i.e.Uma medida de probabilidade para a sequencia {yt} é a mesma para {yt+m} m.

• Um Processo Fracamente Estacionario

Se uma serie satisfaz as três equações abaixo, se diz fracamente ou covariancia

estationaria

1. E(yt) = ,

t = 1,2,...,

2

2. E ( yt )( yt )

3. E ( yt1 )( yt 2 ) t 2 t1 t1 , t2

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

2

Modelos de Series Temporais (cont’d)

• Então se o processo é covariancia estationario, as variancias são as mesmas e as

covariancias dependem da differença entre t1 and t2. Os momentos

E ( yt E ( yt ))( yt s E ( yt s )) s , s = 0,1,2, ...

são conhecidos como a função covariancia.

• As covariancias, s, são conhecidas como autocovariancias.

• Todavia, o valor das autocovariancias dependem das unidades de medida de yt.

• É então mais conveniente usar as autocorrelações que são as autocovariancias

normalizadas dividindo-se pela variancia:

, s = 0,1,2, ...

s s

• Se fizermos o grafico de 0s against s=0,1,2,..então se obtém a função de

autocorrelação ou o correlograma.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

3

Um Processo Ruido Branco

• Um processo ruido branco é um com (virtualmente) estrutura discernivel.

Uma definição de processo ruido branco

é

E( y )

t

Var ( yt ) 2

2 if t r

t r

otherwise

0

• Então, a função de autocorrelação será zero exceto para um unico peak de

1 at s = 0. s aproximadamente N(0,1/T) onde T = tamanho da amostra

• Pode-se usar isto para realizar testes de significancia para os coeficientes

de autocorrelação através da construção de intervalo de confiança.

.196

por

1

T

• Por exemplo, um intervalo de confiança a 95% seria dado

.

Se o coeficiente de autocorrelação, s

fica fora dessa região para

qualquer valor de s, então rejeitamos a hipotese nula de que o valor

verdadeiro do coeficiente no lag s é zero.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

4

Testes de Hipótese Conjunta

• Podemos tambem testar a hipotese conjunta de que todos os m dos coeficientes

de correlação k são simultaneamente iguais a zero com a estatistica Q

m

desenvolvida por Box and

Pierce:

Q T k2

k 1

onde T = tamanho da amostra, m = extensão maxima da defasagem

• A estatistica Q é assintoticamente distribuida

. m2

• Todavia, o teste de Box Pierce tem propriedades pobres em pequenas amostras,

tendo sido desenvolvida uma variante, chamada a estatistica Ljung-Box :

m

Q T T 2

k 1

k2

T k

~ m2

• Esta estatistica é muito util como um teste de dependencia linear em time series.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

5

An ACF Example

• Question:

Suppose that a researcher had estimated the first 5 autocorrelation coefficients

using a series of length 100 observations, and found them to be (from 1 to 5):

0.207, -0.013, 0.086, 0.005, -0.022.

Test each of the individual coefficient for significance, and use both the BoxPierce and Ljung-Box tests to establish whether they are jointly significant.

• Solution:

A coefficient would be significant if it lies outside (-0.196,+0.196) at the 5%

level, so only the first autocorrelation coefficient is significant.

Q=5.09 and Q*=5.26

Compared with a tabulated 2(5)=11.1 at the 5% level, so the 5 coefficients

are jointly insignificant.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

6

Processos de Médias Móveis

• Seja ut (t=1,2,3,...) uma sequencia de variaveis aleatórias distribuidas

identicamente e indepedentemente com E(ut)=0 e Var(ut)= ,2, então

yt = + ut + 1ut-1 + 2ut-2 + ... + qut-q

é um modelo de media movel de qth ordem, MA(q).

• Suas propriedades são

E(yt)=; Var(yt) = 0 = (1+12 22 ... q2 )2

Covariancias

( s s 1 1 s 2 2 ... q q s ) 2

s

0 for s q

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

for

s 1,2,..., q

7

Example of an MA Problem

1. Consider the following MA(2) process:

X t u t 1u t 1 2 u t 2

where t is a zero mean white noise process with variance 2 .

(i) Calculate the mean and variance of Xt

(ii) Derive the autocorrelation function for this process (i.e. express the

autocorrelations, 1, 2, ... as functions of the parameters 1 and

2).

(iii) If 1 = -0.5 and 2 = 0.25, sketch the acf of Xt.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

8

Solution

(i) If E(ut)=0, then E(ut-i)=0 i.

So

E(Xt) = E(ut + 1ut-1+ 2ut-2)= E(ut)+ 1E(ut-1)+ 2E(ut-2)=0

Var(Xt)

but E(Xt)

Var(Xt)

= E[Xt-E(Xt)][Xt-E(Xt)]

= 0, so

= E[(Xt)(Xt)]

= E[(ut + 1ut-1+ 2ut-2)(ut + 1ut-1+ 2ut-2)]

= E[ u t2 12 u t21 22 u t2 2 +cross-products]

But E[cross-products]=0 since Cov(ut,ut-s)=0 for s0.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

9

Solution (cont’d)

So Var(Xt) = 0= E [ u t 1 u t 1 2 u t 2 ]

2

2 2

2 2

= 1 2

2

2

2

= (1 1 2 )

2

2

2

2

2

(ii) The acf of Xt.

1 = E[Xt-E(Xt)][Xt-1-E(Xt-1)]

= E[Xt][Xt-1]

= E[(ut +1ut-1+ 2ut-2)(ut-1 + 1ut-2+ 2ut-3)]

2

2

= E[( 1u t 1 1 2 u t 2 )]

= 1 2 1 2 2

= ( 1 1 2 ) 2

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

10

Solution (cont’d)

2

= E[Xt-E(Xt)][Xt-2-E(Xt-2)]

= E[Xt][Xt-2]

= E[(ut +1ut-1+2ut-2)(ut-2 +1ut-3+2ut-4)]

= E[( 2 u t2 2 )]

2

= 2

3

= E[Xt-E(Xt)][Xt-3-E(Xt-3)]

= E[Xt][Xt-3]

= E[(ut +1ut-1+2ut-2)(ut-3 +1ut-4+2ut-5)]

=0

So s = 0 for s > 2.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

11

Solution (cont’d)

We have the autocovariances, now calculate the autocorrelations:

0 0 1

0

( 1 1 2 ) 2

1

( 1 1 2 )

1

0 (1 12 22 ) 2 (1 12 22 )

( 2 ) 2

2

2

2

0 (1 12 22 ) 2 (1 12 22 )

3 3 0

0

s s 0s 2

0

(iii) For 1 = -0.5 and 2 = 0.25, substituting these into the formulae above

gives 1 = -0.476, 2 = 0.190.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

12

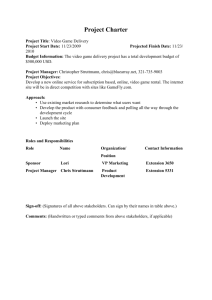

Grafico da ACF

Thus the acf plot will appear as follows:

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

acf

0.4

0.2

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

s

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

13

Processos Autoregressivos

• Um modelo autoregressivo de ordem p, um AR(p) pode ser expresso

como

y t 1 y t 1 2 y t 2 ... p y t p u t

• Ou usando a notação do operador de defasagem:

Lyt = yt-1

Liyt = yt-i

p

y t i y t i u t

i 1

p

y t i Li y t u t

• or

i 1

( L) y t u t

or

( L) 1 (1 L 2 L2 ... p Lp )

where

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

.

14

A Condição de Estacionaridade para um Modelo AR

• The condition for stationarity of a general AR(p) model is that the

roots of 1 1z 2 z2 ... p z p 0 all lie outside the unit circle.

• A stationary AR(p) model is required for it to have an MA()

representation.

• Example 1: Is yt = yt-1 + ut stationary?

The characteristic root is 1, so it is a unit root process (so nonstationary)

• Example 2: Is yt = 3yt-1 - 0.25yt-2 + 0.75yt-3 +ut stationary?

The characteristic roots are 1, 2/3, and 2. Since only one of these lies

outside the unit circle, the process is non-stationary.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

15

Wold’s Decomposition Theorem

• States that any stationary series can be decomposed into the sum of two

unrelated processes, a purely deterministic part and a purely stochastic

part, which will be an MA().

• For the AR(p) model, ( L) yt ut , ignoring the intercept, the Wold

decomposition is

yt ( L)ut

where,

( L) (1 1 L 2 L2 ... p Lp ) 1

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

16

The Moments of an Autoregressive Process

• The moments of an autoregressive process are as follows. The mean is

given by

0

E ( yt )

1 1 2 ... p

• The autocovariances and autocorrelation functions can be obtained by

solving what are known as the Yule-Walker equations:

1 1 12 ... p 1 p

2 11 2 ... p 2 p

p p 11 p 22 ... p

• If the AR model is stationary, the autocorrelation function will decay

exponentially to zero.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

17

Sample AR Problem

• Consider the following simple AR(1) model

yt 1 yt 1 ut

(i) Calculate the (unconditional) mean of yt.

For the remainder of the question, set =0 for simplicity.

(ii) Calculate the (unconditional) variance of yt.

(iii) Derive the autocorrelation function for yt.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

18

Solution

(i) Unconditional mean:

E(yt) = E(+1yt-1)

= +1E(yt-1)

But also

So E(yt)= +1 ( +1E(yt-2))

= +1 +12 E(yt-2))

E(yt) = +1 +12 E(yt-2))

= +1 +12 ( +1E(yt-3))

= +1 +12 +13 E(yt-3)

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

19

Solution (cont’d)

An infinite number of such substitutions would give

E(yt) = (1+1+12 +...) + 1y0

So long as the model is stationary, i.e. , then 1 = 0.

So E(yt) = (1+1+12 +...) =

1 1

(ii) Calculating the variance of yt: yt 1 yt 1 ut

From Wold’s decomposition theorem:

yt (1 1 L) ut

yt (1 1 L) 1 u t

y t (1 1 L 1 L2 ...)u t

2

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

20

Solution (cont’d)

So long as 1 1 , this will converge.

yt ut 1ut 1 1 ut 2 ...

2

Var(yt) = E[yt-E(yt)][yt-E(yt)]

but E(yt) = 0, since we are setting = 0.

Var(yt) = E[(yt)(yt)]

= E[ ut 1ut 1 12ut 2 .. ut 1ut 1 12ut 2 .. ]

= E[(ut 2 12ut 12 14ut 2 2 ... cross products)]

2

2

2

4

2

= E[(ut 1 ut 1 1 ut 2 ...)]

= u2 12 u2 14 u2 ...

2

2

4

= u (1 1 1 ...)

2

u

=

(1 12 )

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

21

Solution (cont’d)

(iii) Turning now to calculating the acf, first calculate the autocovariances:

1 = Cov(yt, yt-1) = E[yt-E(yt)][yt-1-E(yt-1)]

Since a0 has been set to zero, E(yt) = 0 and E(yt-1) = 0, so

1 = E[ytyt-1]

2

2

1 = E[(ut 1ut 1 1 ut 2 ...)(u t 1 1u t 2 1 u t 3 ...) ]

2

3

2

u

u

= E[ 1 t 1

1

t 2 ... cross products]

2

3 2

5 2

= 1 1 1 ...

=

1 2

(1 12 )

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

22

Solution (cont’d)

For the second autocorrelation coefficient,

2 = Cov(yt, yt-2) = E[yt-E(yt)][yt-2-E(yt-2)]

Using the same rules as applied above for the lag 1 covariance

2 = E[ytyt-2]

2

2

= E[(ut 1ut 1 1 ut 2 ...)(ut 2 1ut 3 1 ut 4 ...) ]

= E[ 1 2 u t 2 2 1 4 u t 3 2 ... cross products]

= 12 2 14 2 ...

2 2

2

4

= 1 (1 1 1 ...)

=

12 2

(1 12 )

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

23

Solution (cont’d)

• If these steps were repeated for 3, the following expression would be

obtained

3 =

13 2

(1 12 )

and for any lag s, the autocovariance would be given by

s =

1s 2

(1 12 )

The acf can now be obtained by dividing the covariances by the

variance:

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

24

Solution (cont’d)

0

1

0 =

0

1 2

2

(

1

1 )

1

1

1 =

0

2

2

(

1

1 )

2 =

2

0

2 2

1

2

(

1

1 )

12

2

2

(

1

1 )

3

3 = 1

…

s = 1s

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

25

A Função de Autocorrelação Parcial ( kk)

• Mensura a correlação entre uma observação k periodos atras e a observação

atual, após controlar as observações de defasagens intermediárias (i.e. all

lags < k).

• Portanto, kk mede a correlação entre yt and yt-k após eliminar os efeitos de ytk+1 , yt-k+2 , …, yt-1 .

• No lag 1, a acf = pacf sempre

• No lag 2, 22 = (2-12) / (1-12)

• Para lags 3+, as formulas são mais complexas.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

26

A Função de Autocorrelação Parcial ( kk)

(cont’d)

• A pacf é util para dizer a diferença entre um processo AR e um

processo ARMA .

• No caso de um AR(p), há conexões diretas entre yt e yt-s somente

para s p.

• Então para um AR(p), a pacf teórica será zero após o lag p.

• No caso de um MA(q), isto pode ser escrito como um AR(), daí haver

conexões diretas entre yt e todos os seus valores anteriores.

• Para um MA(q), o pacf teórico será geometricamente declinante.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

27

Processos ARMA

• Combinando os modelos AR(p) e MA(q) , podemos obter um modelo

ARMA(p,q) :

( L) yt ( L)ut

where ( L) 1 1 L 2 L2 ... p Lp

and ( L) 1 1L 2 L2 ... q Lq

or

yt 1 yt 1 2 yt 2 ... p yt p 1u t 1 2 u t 2 ... q u t q u t

2

2

with E(ut ) 0; E(ut ) ; E(ut u s ) 0, t s

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

28

The Invertibility Condition

• Similar to the stationarity condition, we typically require the MA(q) part of

the model to have roots of (z)=0 greater than one in absolute value.

• The mean of an ARMA series is given by

E ( yt )

1 1 2 ...p

• The autocorrelation function for an ARMA process will display

combinations of behaviour derived from the AR and MA parts, but for lags

beyond q, the acf will simply be identical to the individual AR(p) model.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

29

Sumário do Comportamento da acf para os

Processos AR e MA

Um processo autoregressivo tem

• Uma acf que cai geometricamente

• Numero de spikes da pacf = ordem de AR

Um processo de media movel tem

• Numero de spikes da acf = ordem de MA

• Uma pacf que cai geometricamente

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

30

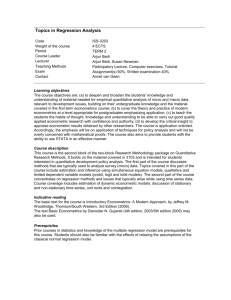

Alguns gráficos de acf e pacf para processos padrão

acf e a pacf não são produzidas analiticamente de formulas relevantes para um modelo

daquele tipo, mas, ao invés, são estimadas usando 100,000 observações simuladas com

disturbancias extraidas de uma distribuição normal.

ACF and PACF for an MA(1) Model: yt = – 0.5ut-1 + ut

A

0.05

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-0.05

acf and pacf

-0.1

-0.15

-0.2

-0.25

-0.3

acf

-0.35

pacf

-0.4

-0.45

Lag

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

31

ACF and PACF for an MA(2) Model:

yt = 0.5ut-1 - 0.25ut-2 + ut

0.4

acf

0.3

pacf

0.2

acf and pacf

0.1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

Lags

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

32

ACF e PACF para um Modelo AR(1), que caem

lentamente:

yt = 0.9yt-1 + ut

1

0.9

acf

pacf

0.8

0.7

acf and pacf

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-0.1

Lags

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

33

ACF e PACF para um Modelo AR(1) que cai mais

rapidamente AR(1) Model: yt = 0.5yt-1 + ut

0.6

0.5

acf

pacf

acf and pacf

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-0.1

Lags

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

34

ACF e PACF para um Modelo AR(1), que cai mais

rapidamente, com Coeficiente Negativo: yt = -0.5yt-1 +

ut

0.3

0.2

0.1

acf and pacf

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

acf

pacf

-0.5

-0.6

Lags

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

35

ACF e PACF para um Modelo Não-estacionario

(i.e. a unit coefficient): yt = yt-1 + ut

1

0.9

acf

pacf

0.8

acf and pacf

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

1

2

3

4

6

5

7

8

9

10

Lags

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

36

ACF e PACF para um ARMA(1,1):

yt = 0.5yt-1 + 0.5ut-1 + ut

0.8

0.6

acf

pacf

acf and pacf

0.4

0.2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-0.2

-0.4

Lags

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

37

A Construção de Modelos ARMA

- A Abordagem de Box Jenkins

• Box e Jenkins (1970) foram os primeiros a abordarem a tarefa de estimar

um modelo ARMA de uma maneira sistematica. Há 3 etapas na sua

abordagem:

1. Identificação

2. Estimação

3. Diagnóstico do Modelo

Etapa 1:

- Envolve a determinação da ordem do modelo.

- Uso de procedimentos de graficos

- Um procedimento melhor está disponivel agora

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

38

A Construção de Modelos ARMA

- A Abordagem de Box Jenkins

Etapa 2:

- Estimação dos parametros

- Pode ser feito usando MQO ou MV a depender do modelo..

Etapa 3:

- Checagem do Modelo

Box and Jenkins sugerem 2 metodos:

- deliberado sobreajustamento

- diagnostico

- diagnostico dos resíduos

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

39

Alguns Desenvolvimentos Mais Recentes na

Modelagem de ARMA

• A identificação não seria tipicamente feita usando acf”s.

• Queremos formar um modelo parcimonioso.

• Razões:

- a variancia dos estimadores é inversamente proporcional ao numero de

graus de liberdade freedom.

- modelos que são profligate podem ser inclinados a dados de carateristicas

especificas

• Isto motiva o uso de criterios de informação, que contém 2 fatores

- um termo que é uma função de RSS

- alguma penalidade por acréscimo de parâmetros extra

• O objetivo é escolher o numero de parametros que minimiza o criterio de

informação.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

40

Critérios de Informação para Escolha de Modelo

• Os criterios de informação variam de acordo com o termo da penalidade.

• Os três critérios mais populares são o critério de informação de Akaike

(1974) (AIC), o critério Bayesiano de informação de Schwarz (1978)

(SBIC), e o critério de Hannan-Quinn (HQIC).

AIC ln( 2 ) 2k / T

k

SBIC ln( ˆ 2 ) ln T

T

2k

HQIC ln( ˆ 2 )

ln(ln( T ))

T

where k = p + q + 1, T = sample size. So we min. IC s.t. p p, q q

SBIC incorpora uma penalidade maior que AIC.

• Que C I deve ser preferido se eles sugerem ordens diferentes de modelo?

– SBIC é fortemente consistente mas (ineficiente).

– AIC não é consistente, e pegará tipicamente modelos maiores

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

41

Modelos ARIMA

• Diferentes dos modelos ARMA. O I significa integrado.

• Um processo autoregressivo integrado é um com uma raiz

caracteristica no circulo unitário.

• Os pesquisadores diferenciam a variavel como necessaria e então

constroem um modelo ARMA com aquelas variaveis diferenciadas.

• Um modelo ARMA(p,q) na

variavel diferenciada d vezes é

equivalente a um modelo ARIMA(p,d,q) nos dados originais.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

42

Exponential Smoothing

• Another modelling and forecasting technique

• How much weight do we attach to previous observations?

• Expect recent observations to have the most power in helping to forecast

future values of a series.

• The equation for the model

St = yt + (1-)St-1

where

is the smoothing constant, with 01

yt

is the current realised value

St

is the current smoothed value

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

(1)

43

Exponential Smoothing (cont’d)

• Lagging (1) by one period we can write

St-1 = yt-1 + (1-)St-2

• and lagging again

St-2 = yt-2 + (1-)St-3

• Substituting into (1) for St-1 from (2)

St

= yt + (1-)( yt-1 + (1-)St-2)

= yt + (1-) yt-1 + (1-)2 St-2

(2)

(3)

(4)

• Substituting into (4) for St-2 from (3)

St

= yt + (1-) yt-1 + (1-)2 St-2

= yt + (1-) yt-1 + (1-)2( yt-2 + (1-)St-3)

= yt + (1-) yt-1 + (1-)2 yt-2 + (1-)3 St-3

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

44

Exponential Smoothing (cont’d)

• T successive substitutions of this kind would lead to

T

i

T

St 1 yt i 1 S0

i 0

since 0, the effect of each observation declines exponentially as we

move another observation forward in time.

• Forecasts are generated by

ft+s = St

for all steps into the future s = 1, 2, ...

• This technique is called single (or simple) exponential smoothing.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

45

Exponential Smoothing (cont’d)

•

–

–

–

–

It doesn’t work well for financial data because

there is little structure to smooth

it cannot allow for seasonality

it is an ARIMA(0,1,1) with MA coefficient (1-) - (See Granger & Newbold, p174)

forecasts do not converge on long term mean as s

• Can modify single exponential smoothing

– to allow for trends (Holt’s method)

– or to allow for seasonality (Winter’s method).

• Advantages of Exponential Smoothing

– Very simple to use

– Easy to update the model if a new realisation becomes available.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

46

Previsão em Econometria

• Forecasting = prediction.

• Um teste importante da adequacão de um modelo.

e.g.

- Prever o retorno de uma determinada ação amanhã

- Prever o preço de uma casa dadas as suas caracteristicas

- Prever o risco de um portfolio ao longo do próximo ano

- Prever a volatilidade de retornos de bonds

• Podemos distinguir duas abordagens:

- Previsão econometrica (estructural)

- Previsão de series temporais

• The distinction between the two types is somewhat blurred (e.g, VARs).

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

47

In-Sample Versus Out-of-Sample

• Expect the “forecast” of the model to be good in-sample.

• Say we have some data - e.g. monthly FTSE returns for 120 months:

1990M1 – 1999M12. We could use all of it to build the model, or keep

some observations back:

• A good test of the model since we have not used the information from

1999M1 onwards when we estimated the model parameters.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

48

How to produce forecasts

• Multi-step ahead versus single-step ahead forecasts

• Recursive versus rolling windows

• To understand how to construct forecasts, we need the idea of conditional

expectations:

E(yt+1 t )

• We cannot forecast a white noise process: E(ut+s t ) = 0 s > 0.

• The two simplest forecasting “methods”

1. Assume no change : f(yt+s) = yt

2. Forecasts are the long term average f(yt+s) = y

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

49

Models for Forecasting

• Structural models

e.g.

y = X + u

yt 1 2 x2t k xkt ut

To forecast y, we require the conditional expectation of its future

value:

Eyt t 1 E1 2 x2t k xkt ut

= 1 2 E x2t k E xkt

But what are ( x 2t ) etc.? We could use x 2 , so

E yt 1 2 x2 k xk

= y !!

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

50

Models for Forecasting (cont’d)

• Time Series Models

The current value of a series, yt, is modelled as a function only of its previous

values and the current value of an error term (and possibly previous values of

the error term).

• Models include:

• simple unweighted averages

• exponentially weighted averages

• ARIMA models

• Non-linear models – e.g. threshold models, GARCH, bilinear models, etc.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

51

Forecasting with ARMA Models

The forecasting model typically used is of the form:

p

q

i 1

j 1

f t , s i f t , s i j ut s j

where ft,s = yt+s , s 0; ut+s = 0, s > 0

= ut+s , s 0

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

52

Forecasting with MA Models

• An MA(q) only has memory of q.

e.g. say we have estimated an MA(3) model:

yt = + 1ut-1 + 2ut-2 + 3ut-3 + ut

yt+1 = + 1ut + 2ut-1 + 3ut-2 + ut+1

yt+2 = + 1ut+1 + 2ut + 3ut-1 + ut+2

yt+3 = + 1ut+2 + 2ut+1 + 3ut + ut+3

• We are at time t and we want to forecast 1,2,..., s steps ahead.

• We know yt , yt-1, ..., and ut , ut-1

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

53

Forecasting with MA Models (cont’d)

ft, 1 = E(yt+1 t )

=

=

E( + 1ut + 2ut-1 + 3ut-2 + ut+1)

+ 1ut + 2ut-1 + 3ut-2

ft, 2 = E(yt+2 t )

=

=

E( + 1ut+1 + 2ut + 3ut-1 + ut+2)

+ 2ut + 3ut-1

ft, 3 = E(yt+3 t )

=

=

E( + 1ut+2 + 2ut+1 + 3ut + ut+3)

+ 3ut

ft, 4 = E(yt+4 t )

=

ft, s = E(yt+s t )

=

s4

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

54

Forecasting with AR Models

• Say we have estimated an AR(2)

yt = + 1yt-1 + 2yt-2 + ut

yt+1 = + 1yt + 2yt-1 + ut+1

yt+2 = + 1yt+1 + 2yt + ut+2

yt+3 = + 1yt+2 + 2yt+1 + ut+3

ft, 1 = E(yt+1 t ) = E( + 1yt + 2yt-1 + ut+1)

= + 1E(yt) + 2E(yt-1)

= + 1yt + 2yt-1

ft, 2 = E(yt+2 t ) = E( + 1yt+1 + 2yt + ut+2)

= + 1E(yt+1) + 2E(yt)

= + 1 ft, 1 + 2yt

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

55

Forecasting with AR Models (cont’d)

ft, 3 = E(yt+3 t ) = E( + 1yt+2 + 2yt+1 + ut+3)

= + 1E(yt+2) + 2E(yt+1)

= + 1 ft, 2 + 2 ft, 1

• We can see immediately that

ft, 4 = + 1 ft, 3 + 2 ft, 2 etc., so

ft, s = + 1 ft, s-1 + 2 ft, s-2

• Can easily generate ARMA(p,q) forecasts in the same way.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

56

How can we test whether a forecast is accurate or not?

•For example, say we predict that tomorrow’s return on the FTSE will be 0.2, but

the outcome is actually -0.4. Is this accurate? Define ft,s as the forecast made at

time t for s steps ahead (i.e. the forecast made for time t+s), and yt+s as the

realised value of y at time t+s.

• Some of the most popular criteria for assessing the accuracy of time series

forecasting techniques are:

1

MSE

N

1

MAE is given by MAE

N

N

t 1

N

t 1

( yt s f t , s ) 2

yt s f t , s

1 N yt s ft ,s

Mean absolute percentage error: MAPE 100

N t 1

yt s

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

57

How can we test whether a forecast is accurate or not?

(cont’d)

• It has, however, also recently been shown (Gerlow et al., 1993) that the

accuracy of forecasts according to traditional statistical criteria are not

related to trading profitability.

• A measure more closely correlated with profitability:

1 N

zt s

% correct sign predictions =

N t 1

where

zt+s = 1 if (xt+s . ft,s ) > 0

zt+s = 0 otherwise

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

58

Forecast Evaluation Example

• Given the following forecast and actual values, calculate the MSE, MAE and

percentage of correct sign predictions:

Steps Ahead

1

2

3

4

5

Forecast

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.06

0.04

Actual

-0.40

0.20

0.10

-0.10

-0.05

• MSE = 0.079, MAE = 0.180, % of correct sign predictions = 40

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

59

What factors are likely to lead to a

good forecasting model?

• “signal” versus “noise”

• “data mining” issues

• simple versus complex models

• financial or economic theory

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

60

Statistical Versus Economic or

Financial loss functions

• Statistical evaluation metrics may not be appropriate.

• How well does the forecast perform in doing the job we wanted it for?

Limits of forecasting: What can and cannot be forecast?

• All statistical forecasting models are essentially extrapolative

• Forecasting models are prone to break down around turning points

• Series subject to structural changes or regime shifts cannot be forecast

• Predictive accuracy usually declines with forecasting horizon

• Forecasting is not a substitute for judgement

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

61

Back to the original question: why forecast?

• Why not use “experts” to make judgemental forecasts?

• Judgemental forecasts bring a different set of problems:

e.g., psychologists have found that expert judgements are prone to the

following biases:

– over-confidence

– inconsistency

– recency

– anchoring

– illusory patterns

– “group-think”.

• The Usually Optimal Approach

To use a statistical forecasting model built on solid theoretical

foundations supplemented by expert judgements and interpretation.

‘Introductory Econometrics for Finance’ © Chris Brooks 2002

62