Hannah 10 poems

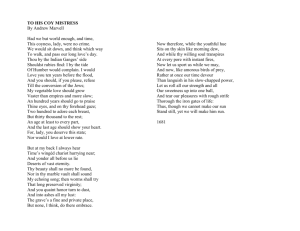

advertisement

Patience by Kay Ryan Patience is wider than one once envisioned, with ribbons of rivers and distant ranges and tasks undertaken and finished with modest relish by natives in their native dress. Who would have guessed it possible that waiting is sustainable— a place with its own harvests. Or that in time's fullness the diamonds of patience couldn't be distinguished from the genuine in brilliance or hardness. Hyperby David Baker Then a stillness descended the blue hills. I say stillness. They were three deer, then four. They crept down the old bean field, these four deer, for fifteen minutes—more—as we watched them in the field, in the soughing snow. That's how slowly they moved in stillness, slender deer. The fourth limped behind the other three, we could see, even in the darkness, as it dragged its right hindquarter where it was hit or shot. Katie sat back on her heels. The dog held in his prints, or Kate held him, hardly breathing at first. Then we relaxed. Blue night descended our neighbor's blown hills. And the calm that comes with seeing something beautiful but far from perfect descended— absolute attention, a fixity. I say absolute. It was stillness. In the books we gathered, the first theory holds that the condition's emergence is most common at age eight, if less in girls than boys, or more vividly seen in boys whose fidgets, whose deficit attentions, like little psycho-economic realms, are prone to twitches-turned-to-virulence, anxieties palpable in vocalized explosions—though now we know in girls it's only on the surface less severe, which explains her months of bubbling tension, her long blue drifts and snowy distractions. I say distractions. Of course I mean how, clinically, tyrosine hydroxylase activity—the "rate limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis"—disrupts, burns, then rewires her brain's chemical pathways. Let me put it another way. After twenty-four math problems, the twenty-fifth still baffles her, pencil gnawed, eraserscuff-shadows like black veins on her homework. It's not just the theory of division she no longer gets, it's her hot clothes, her itchy ear, the ruby-throated hummingbird's picture on the fridge, what's in the fridge, whose socks these are, why, until I'm exhausted and yell again. Until she's gone away to her room, lights off, to sulk, read, cry, draw. No longer trusting to memory, she writes everything in her journal now, then ties it with a broken strand of necklace. Of her friends: I am the funny one. Mom: She has red hair and freckles to. Under Dad: I have his bad temper. I know. I looked. In one sketch she finished, just before we learned what was wrong—I mean, before we knew what to call what was wrong, how to treat it, how to treat her—she captured her favorite cat with a skill that skips across my chest. He's on a throw rug, asleep. The rug's fringe ruffles just so. The measure of her love is visible in each delicate stroke, from his fetal repose, ears down, eyes sealed softly, paws curled inward, to the tiger lines of his coat deepened by thick textures where she's slightly rubbed away the contours with her thumb to winter coat gray. He's soft, he's purring, he's utterly relaxed asleep. One day, before we learned what was wrong, she taped it to a pillow on my bed. Terry Is Tired she'd printed at the top. How many ways do we measure things by what they're not. I say things. Mostly her mind is going too fast, yet the doctors give her, I'm not kidding, amphetamines— speed, we used to say, when we needed it— Ritalin, which wears off hard and often, Adderal, which lasts all day though her food's untouched and sleep comes late. The irony is the medicine slows her down. She pays attention, understands things. The theory is, AD/HD patients "aren't hyperaroused, they're underaroused," so they lurch and hurtle forward, hungry for focus. Another theory says the brain's two lobes are missized. Their circuits "lose their balance." One makes much of handedness—left—red hair, allergies, wan skin, an Irish past . . . We watched four deer in stillness walking there. Stillness walking, like the young blue deer hurt but beautiful. In her theory of division, Katie's started drawing them— her rendering's reduced them down to three. She has carefully lined the cut bean rows in contours like the dog's brushed coat. Snowflakes dot the winter paper. Two small deer stand alert on either side of the hurt one leaning now to bite the season's dried-up stems. Their ears are perched like hands, noses up, tails tufted in a hundred tiny pencil lines. She's been hunkered over her drawing pad, humming, for an hour. So I watch. I say watch. I ask why she's made the little hurt one so big. Silly. He's not hurt that bad, she says. She doesn't look up. That one's you. Bed in Summer by Robert Louis Stevenson In winter I get up at night And dress by yellow candle-light. In summer, quite the other way, I have to go to bed by day. I have to go to bed and see The birds still hopping on the tree, Or hear the grown-up people’s feet Still going past me in the street. And does it not seem hard to you, When all the sky is clear and blue, And I should like so much to play, To have to go to bed by day? In Summer by Paul Laurence Dunbar Oh, summer has clothed the earth In a cloak from the loom of the sun! And a mantle, too, of the skies' soft blue, And a belt where the rivers run. And now for the kiss of the wind, And the touch of the air's soft hands, With the rest from strife and the heat of life, With the freedom of lakes and lands. I envy the farmer's boy Who sings as he follows the plow; While the shining green of the young blades lean To the breezes that cool his brow. He sings to the dewy morn, No thought of another's ear; But the song he sings is a chant for kings And the whole wide world to hear. He sings of the joys of life, Of the pleasures of work and rest, From an o'erfull heart, without aim or art; 'T is a song of the merriest. O ye who toil in the town, And ye who moil in the mart, Hear the artless song, and your faith made strong Shall renew your joy of heart. Oh, poor were the worth of the world If never a song were heard,— If the sting of grief had no relief, And never a heart were stirred. So, long as the streams run down, And as long as the robins trill, Let us taunt old Care with a merry air, And sing in the face of ill. Summer Night, Riverside by Sara Teasdale In the wild soft summer darkness How many and many a night we two together Sat in the park and watched the Hudson Wearing her lights like golden spangles Glinting on black satin. The rail along the curving pathway Was low in a happy place to let us cross, And down the hill a tree that dripped with bloom Sheltered us, While your kisses and the flowers, Falling, falling, Tangled in my hair.... The frail white stars moved slowly over the sky. And now, far off In the fragrant darkness The tree is tremulous again with bloom For June comes back. To-night what girl Dreamily before her mirror shakes from her hair This year's blossoms, clinging to its coils? Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. "Beware the Jabberwock, my son The jaws that bite, the claws that catch! Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun The frumious Bandersnatch!" He took his vorpal sword in hand; Long time the manxome foe he sought— So rested he by the Tumtum tree, And stood awhile in thought. And, as in uffish thought he stood, The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame, Came whiffling through the tulgey wood, And burbled as it came! One, two! One, two! And through and through The vorpal blade went snicker-snack! He left it dead, and with its head He went galumphing back. "And hast thou slain the Jabberwock? Come to my arms, my beamish boy! O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!" He chortled in his joy. 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. A Blessing by James Wright Just off the highway to Rochester, Minnesota, Twilight bounds softly forth on the grass. And the eyes of those two Indian ponies Darken with kindness. They have come gladly out of the willows To welcome my friend and me. We step over the barbed wire into the pasture Where they have been grazing all day, alone. They ripple tensely, they can hardly contain their happiness That we have come. They bow shyly as wet swans. They love each other. There is no loneliness like theirs. At home once more, They begin munching the young tufts of spring in the darkness. I would like to hold the slenderer one in my arms, For she has walked over to me And nuzzled my left hand. She is black and white, Her mane falls wild on her forehead, And the light breeze moves me to caress her long ear That is delicate as the skin over a girl's wrist. Suddenly I realize That if I stepped out of my body I would break Into blossom. Ode to Spring by Frederick Seidel I can only find words for. And sometimes I can't. Here are these flowers that stand for. I stand here on the sidewalk. I can't stand it, but yes of course I understand it. Everything has to have meaning. Things have to stand for something. I can't take the time. Even skin-deep is too deep. I say to the flower stand man: Beautiful flowers at your flower stand, man. I'll take a dozen of the lilies. I'm standing as it were on my knees Before a little man up on a raised Runway altar where his flowers are arrayed Along the outside of the shop. I take my flames and pay inside. I go off and have sexual intercourse. The woman is the woman I love. The room displays thirteen lilies. I stand on the surface. Cradle Song by William Blake Sleep, sleep, beauty bright, Dreaming in the joys of night; Sleep, sleep; in thy sleep Little sorrows sit and weep. Sweet babe, in thy face Soft desires I can trace, Secret joys and secret smiles, Little pretty infant wiles. As thy softest limbs I feel Smiles as of the morning steal O'er thy cheek, and o'er thy breast Where thy little heart doth rest. O the cunning wiles that creep In thy little heart asleep! When thy little heart doth wake, Then the dreadful night shall break. The City by C. P. Cavafy translated by Edmund Keeley You said: "I'll go to another country. go to another shore, find another city better than this one. Whatever I try to do is fated to turn out wrong and my heart lies buried like something dead. How long can I let my mind moulder in this place? Wherever I turn, wherever I look, I see the black ruins of my life, here, where I've spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed them totally." You won't find a new country, won't find another shore. This city will always pursue you. You'll walk the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods, turn gray in these same houses. You'll always end up in this city. Don't hope for things elsewhere: there's no ship for you, there's no road. Now that you've wasted your life here, in this small corner, you've destroyed it everywhere in the world.