The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker

advertisement

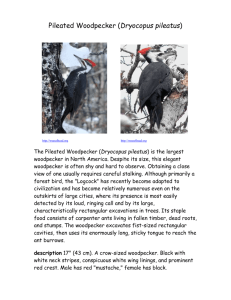

The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Long thought to be extinct, the ivory-billed woodpecker—our nation’s largest and most impressive woodpecker— has made what seems to be a stunning reappearance in the Southeast. This is the story of the bird, its disappearance and rediscovery. Valued by Native Americans for its unique white bill, the ivory-bill was first documented by Europeans during the colonial period by naturalist Mark Catesby. Visiting the Carolinas in the 1720s, Catesby published a description and illustration of an ivory-bill in his 1731 work Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. Throughout the colonial and antebellum periods, the ivory-bill persisted in the secluded river bottomlands and swamps of the South. They seemed most plentiful in South Carolina, Florida, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, though documentation during that time is somewhat limited. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, large-scale logging operations moved into the South and devastated old-growth hardwood forests throughout the region. With this loss of habitat, the ivory-bill began a rapid decline toward extinction. Found only in dead (but not completely rotten) trees, the cerambycid beetle larva is the primary food of the ivory-bill. With loss of habitat came loss of food source and an inevitable slide toward extinction. Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Stats Height: Wingspan: Life Expectancy: Markings: 18”-21” 30”-32” up to 15 years black plumage w/white highlights on wings & back, whitish bill/beak, male - red crest, female - black crest Pileated Woodpecker Stats Height: Wingspan: Life Expectancy: Markings: 16”-19” 26”-30” up to 10 years black plumage w/white highlights on head & wings, gray bill/beak, male & female have red crest As suitable habitat dwindled, the search for ivory-bill specimens soared. Ornithologists, birders, collectors, and curators all sought to “get while the gettin’ was good.” Complete birds, as well as parts, were bought by museums, fashion designers, and the curious. During that time, serious scientific study rarely used live specimens. In 1935, a team led by Cornell’s Arthur A. Allen visited the Singer Tract in Louisiana to document one of the nation’s last known populations of ivory-bills. They captured the sights and sounds of an up-close encounter with a nesting pair and their offspring. Sonny, as they referred to the young bird, was more than eager to cooperate. The last confirmed sighting of an ivory-bill in the United States was in the Singer Tract in 1944. Subsequent searches turned up nesting and feeding evidence as well as sporadic sightings which were largely discredited for one reason or another. Ivory-bills persisted in eastern Cuba until the last confirmed sighting in 1987. Since then, evidence for their existence is inconclusive. In 1999, David Kulivan, a graduate student in forestry at LSU, reported seeing a pair of ivory-bills while turkey hunting in the Pearl River area of southeastern Louisiana. The credibility of this sighting led to a renewed search for the ivory-bill. A 2004 sighting by Gene Sparling in the Big River area of Arkansas led to a secret year-long expedition by Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology, the Nature Conservancy, and other birding experts and sound and video technicians. The search resulted in several sightings, but no conclusive evidence to confirm them. After Cornell broke the news in 2005, the birding world was divided. While all wanted the bird to be alive, many questioned the validity of the evidence and the scientific judgment of those involved. After the 2008-2009 search, Cornell suspended its effort in Arkansas. In September 2006, a joint team from Auburn University and the University of Windsor, Ontario announced the presence of ivory-bills in the Choctawhatchee River area of the Florida panhandle. They made hundreds of audio recordings of the bird’s unique kent calls and doubleknocks, as well as field sketches documenting their fourteen visual sightings. Recent searches have turned up inconclusive evidence: provocative video footage and promising audio recordings, but no definitive proof of the bird’s existence. Future searches will be undertaken on a very limited scale. Singer Tract, Louisiana, 1935 Ivory-billed Pileated Male Female Comparative specimens of the Imperial, Ivory-billed, and Pileated woodpeckers Identification Chart Sources The Grail Bird: Hot on the Trail of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Tim Gallagher, Houghton Mifflin, New York, 2005. In Search of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. Jerome A. Jackson, Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C., 2004. The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. James T. Tanner, Dover Publications, 2003 (Originally published 1942 by National Audubon Society). The Race to Save the Lord God Bird. Philip Hoose, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2004. http://www.npr.org/programs/re/archivesdate/2002/march/ http://www.ivorybill.org/ http://www.birds.cornell.edu/ivory http://www.auburn.edu/academic/science_math/cosam/dep artments/biology/faculty/webpages/hill/ivorybill/ http://www.bobbyharrison.com/ http://www.nature.org/pressroom/features/ See you in the swamp! Pollman’s Ivory-bills