Plessy - US Government

advertisement

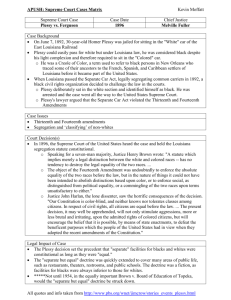

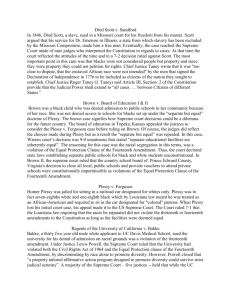

Homer Adolph Plessy a.k.a. The 1/8th Wonder from Down-Under In 1890, Louisiana passed a statute called the "Separate Car Act". This law declared that all rail companies carrying passengers in Louisiana had to provide separate but equal accommodations for white and non-white passengers. The penalty for sitting in the wrong compartment was a fine of $25 or 20 days in jail. Two parties wanted to challenge the constitutionality of the Separate Car Act. A group of black citizens who raised money to overturn the law worked together with the East Louisiana Railroad Company, which sought to terminate the Act largely for monetary reasons. They chose a 30-year-old shoemaker named Homer Plessy, a citizen of the United States who was one-eighth black and a resident of the state of Louisiana. On June 7, 1892, Plessy purchased a first-class passage from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana and sat in the railroad car for "White" passengers. The railroad officials knew Plessy was coming and arrested him for violating the Separate Car Act. Well known advocate for black rights Albion Tourgee, a white lawyer, agreed to argue the case for free. Plessy argued in court that the Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. The Thirteenth Amendment banned slavery and the Fourteenth Amendment requires that the government treat people equally. John Howard Ferguson, the judge hearing the case, had stated in a previous court decision that the Separate Car Act was unconstitutional if applied to trains running outside of Louisiana. In this case, however, he declared that the law was constitutional for trains running within the state and found Plessy guilty. Plessy appealed the case to the Louisiana State Supreme Court, which affirmed the decision that the Louisiana law was constitutional. Plessy then took his case, Plessy v. Ferguson, to the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest court in the country. Judge John Howard Ferguson was named in the case because he had been named in the petition to the Louisiana State Supreme Court, not because he was a party to the initial lawsuit. Outcome: -In a 7-1 decision (1 judge abstained), the Supreme Court Decided: 1.) The Court upheld the Louisiana State Supreme Court's decision and declared that the "Separate Car Act" was constitutional as long as there were separate but equal accommodations for both whites and blacks. It further stated that the legal distinction made by the Act did not in any way destroy the legal equality of the two races. As to the question Plessy raised in his petition to the Louisiana State Supreme Court about his not being black, the Supreme Court of the United States recognized that it may be an important question, but the question was not properly put in issue in this case. Actually, it’s not as difficult as you might think… -For this activity, I want you to partner up (that means only one) with someone close to you. -Then, read each of the following questions, -Discuss your thoughts with your partner, -Come to a mutual agreement, -Write your mutual agreement on a single sheet of paper. Make sure both names are on the paper. 1.) A man and a woman apply for a job as a shoe sales person. What would the employer have to do to treat these two applicants equally? 2.) Two patients come to a doctor with a headache. The doctor determines that one patient has a brain tumor and the other patient has a run-of-the mill headache. What would the doctor have to do to treat these two patients equally? 3.) Two students try to enter a school that has stairs leading to the entrance. One student is handicapped and the other is not. What would the school have to do to treat these two students equally? Linda Brown In Topeka, Kansas in the 1950s, schools were segregated by race. Each day, Linda Brown and her sister, Terry Lynn, had to walk through a dangerous railroad switchyard to get to the bus stop for the ride to their allblack elementary school. There was a school closer to the Brown's house, but it was only for white students. Topeka was not the only town to experience segregation. Segregation in schools and other public places was common throughout the South and elsewhere. This segregation based on race was legal because of a landmark Supreme Court case called Plessy v. Ferguson, which was decided in 1896. In that case, the Court said that as long as segregated facilities were equal in quality segregation did not violate the Constitution. However, the Brown's disagreed. Linda Brown and her family believed that the segregated school system did violate the Constitution. In particular, they believed that the system violated the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing that people will be treated equally under the law. No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. —Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) helped the Browns. Thurgood Marshall was the attorney who argued the case for the Browns. He would later become a Supreme Court justice. The case was first heard in a federal district court, the lowest court in the federal system. The federal district court decided that segregation in public education was harmful to black children. However, the court said that the all-black schools were equal to the all-white schools because the buildings, transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of the teachers were similar; therefore the segregation was legal. The Browns, however, believed that even if the facilities were similar, segregated schools could never be equal to one another. They appealed their case to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court combined the Brown's case with other cases from South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. The ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education case came in 1954. Outcome: -In a 9-0 unanimous vote, the Supreme Court decided: 1.) Ruling determined that segregated schools are "inherently unequal" and violate the Fourteenth Amendment. 2.) Declared that schools should be desegregated with "all deliberate speed." ACTIVITY CENTERS TIME!! Please pay attention to and remember which group you are in. -Students that are “Triangles” need to summarize, in a MEAL paragraph (minimum 7 sentences), the Plessy case. Then, they need to do a 3-2-1 Levels of Questioning for the Plessy case. You will be quizzed as a group after you finish. -Students that are “Circles” need to summarize, in a MEAL paragraph (minimum 8 sentences), the Brown case. Then, they need to 3-2-1 Levels of Questioning for the Brown Case. You will be quizzed as a group after you finish. -Students that are “Squares” need to write their name on the board, and meet Ms. Richardson at the front for their activity. (Raise your hand.) Allan Bakke Beginning in the early 1970s, the medical school of the University of California at Davis used a two-part admissions program for the 100 students entering each year: a regular admissions program and a special admissions program. The purpose of this program was to try to increase the number of minority and "disadvantaged" students in the class, so the 16 spots in the special admissions program were reserved for "qualified" minority and disadvantaged students. Under the regular admissions program, if a candidate had an overall undergraduate grade point average below 2.5 on a scale of 4.0, the candidate was automatically rejected. Candidates who were not automatically rejected were evaluated using other criteria such as math and science grades, MCAT scores, letters of recommendation, and an interview. On the application form, candidates could indicate that they wanted to be considered economically and/or educationally disadvantaged or members of a minority group. Applications of those who did so were sent to the special admissions program where a separate committee, composed mainly of members of minority groups, evaluated them. The applicants in the special admissions program did not have to meet the same standards as the regular candidates, including the 2.5 grade point average cut off. From 1971 to 1974 the special program resulted in the admission of 21 black students, 30 Mexican Americans, and 12 Asians, for a total of 63 minority students.* During the same period, the regular admissions program admitted 1 black student, 6 Mexican Americans, and 37 Asians, for a total of 44 minority students. No disadvantaged white candidates received admission through the special program. Allan Bakke was a white male who applied to and was rejected from the regular admissions program in 1973 and 1974. During those years, applicants with lower scores were admitted under the special program. After his second rejection, Bakke filed suit in the Superior Court of Yolo County, California. He claimed that the special admissions program violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because it excluded him on the basis of race. He wanted the Court to force the University of California at Davis to admit him to the medical school. The Superior Court of Yolo County, California and the Supreme Court of California both found that the special admissions program violated the federal and state constitutions, as well as Title VI, and was therefore illegal. The Superior Court declared that race could not be taken into account when making admissions decisions but also ruled that Bakke should not be admitted to the medical school because he failed to show that he would have been admitted even without the special admissions program. The Supreme Court of California, however, determined that Bakke should be admitted to the school. Outcome: -In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court decided: 1.) Writing for a divided Court, Justice Powell holds that the quota system used by the University of California at Davis medical school is unconstitutional, but that race could be used as a "plus" in the application process. **kind of. 1995 Facts of the Case: • Adarand, a contractor specializing in highway guardrail work, submitted the lowest bid as a subcontractor for part of a project funded by the United States Department of Transportation. Under the terms of the federal contract, the prime contractor would receive additional compensation if it hired small businesses controlled by "socially and economically disadvantaged individuals." [The clause declared that "the contractor shall presume that socially and economically disadvantaged individuals include Black Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Asian Pacific Americans, and other minorities...." Federal law requires such a subcontracting clause in most federal agency contracts]. Another subcontractor, Gonzales Construction Company, was awarded the work. It was certified as a minority business; Adarand was not. The prime contractor would have accepted Adarand's bid had it not been for the additional payment for hiring Gonzales. Question • Is the presumption of disadvantage based on race alone, and consequent allocation of favored treatment, a discriminatory practice that violates the equal protection principle embodied in the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment? Conclusion • In a 5-4 decision the answer is: Yes. Overruling Metro Broadcasting (497 US 547), the Court held that all racial classifications, whether imposed by federal, state, or local authorities, must pass strict scrutiny review. In other words, they "must serve a compelling government interest, and must be narrowly tailored to further that interest." The Court added that compensation programs which are truly based on disadvantage, rather than race, would be evaluated under lower equal protection standards. However, since race is not a sufficient condition for a presumption of disadvantage and the award of favored treatment, all race-based classifications must be judged under the strict scrutiny standard. Moreover, even proof of past injury does not in itself establish the suffering of present or future injury. The Court remanded for a determination of whether the Transportation Department's program satisfied strict scrutiny.