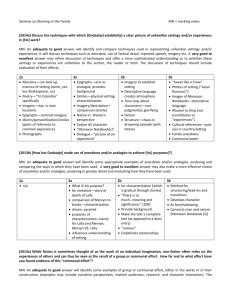

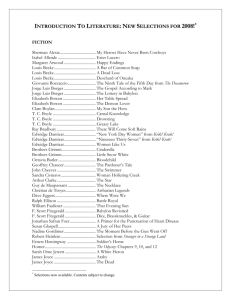

Running in the Family: Family Tree & Timeline Burnt furniture marry

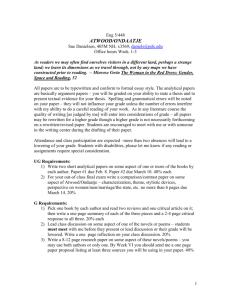

advertisement