Miranda v. Arizona 384 U.S. 436 (1966) Facts: Ernesto A. Miranda

advertisement

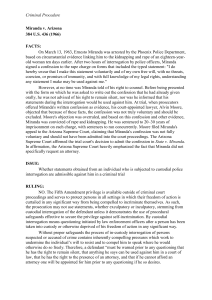

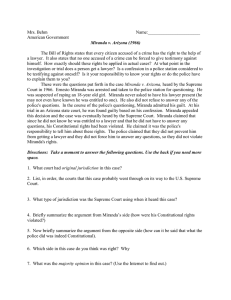

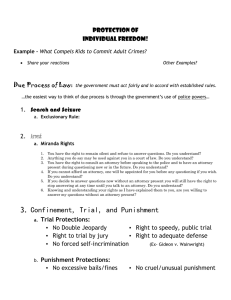

Miranda v. Arizona 384 U.S. 436 (1966) Facts: Ernesto A. Miranda was arrested by the police in Phoenix, Arizona, and interrogated about a kidnapping and rape. After two hours of police questioning, he signed a confession stating that he was making the confession voluntarily with full knowledge of his legal rights and that he understood that any statement he made might be used against him. The confession was used as evidence at his trial, and he was convicted of rape and kidnapping. Miranda appealed the court’s decision claiming that his confession was invalid because it was coerced and because the police never advised him of his right to an attorney or his right to avoid self-incrimination. The Supreme Court of Arizona affirmed the decision of the lower court and the case was appealed to the United States Supreme Court. Issue: Did statements made while being subjected to custodial police investigation have to meet certain standards before they were admissible as evidence in a trial? Decision: Yes. Reasoning: Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Warren stated, "[T]he mere signing of a typed clause that [the defendant] had full knowledge of his legal rights does not approach the knowing and intelligent waiver required to relinquish constitutional rights." Warren indicated that the prosecution could not use statements resulting from a "custodial interrogation" unless the prosecution could show that proper procedures had been used to protect the defendant's privilege against self-incrimination. Custodial interrogation referred to questioning by police "after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way". The Chief Justice then defined the proper procedures to be followed. "Prior to any questioning, the person must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed. The defendant may waive these rights, provided the waiver is made voluntarily, knowingly and intelligently. If, however, he indicates in any manner and at any stage of the process that he wishes to consult with an attorney before speaking there can be no questioning. Likewise, if the individual is alone and indicates in any manner that he does not wish to be interrogated, the police may not question him. The mere fact that he may have answered some questions or volunteered some statements on his own does not deprive him of the right to refrain from answering any further inquiries until he has consulted with an attorney and thereafter consents to be questioned."