Tyranny and the Polis

advertisement

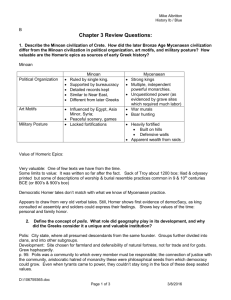

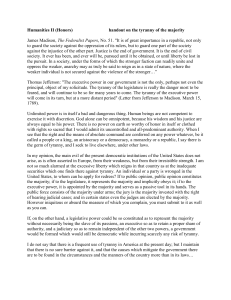

Tyranny and the Polis “A tyrant was roughly what we should call a dictator, a man who obtained sole power in the state and held it in defiance of any constitution that had existed previously.” A. Andrewes, The Greek Tyrants What is a Polis? Origins? Physical Characteristics? The “Spiritual Universe” of the Polis? Types of Government? Historical Developments and Tyranny Dark-Age Monarchy (petty kings or basileis) Aristocracy (dual kingship survives at Sparta) Aristoi = “best men” Hereditary groups claiming descent from first king or ‘founder’ of the polis (Eupatridae at Athens, Bacchiadae at Corinth, Hippeis at Eretria) Evidence: fragments of Solon and Alcaeus, Homer, Institutional Survivals (king-archon at Athens), Herodotus (ca. 430 BCE), Later Political Theorists (Plato, Polybius) Political and Material Preconditions of the Early Poleis Agrarian Economy at Subsistence Level Aristoi Claim Hereditary Political Rights and Privileges Competition Among Great Aristocratic Clans Population Growth and the Limits of the Polis’ Resources Tyranny’s Heyday, Dangers of Historical Generalization 7th and 6th Centuries BCE (ca. 650-510) Autocratic power seized in times of crisis arising from external threats and/or internal tensions (tyrant employs bands of mercenaries as personal bodyguard) Tyranny as Phenomenon of Political Transition Result of abuse of aristocratic privilege Hesiod, Works and Days (ca. 750-700 BCE?): “Keep her [Justice’s] commands, O gift-devouring kings, and let verdicts be straight; yes, lay your crooked ways aside!” (lines 263-264) Crises of small farmers and debt-bondage (Miletos, Athens, Samos, Syracuse) Neutrality of the word tyrannos (pejorative meaning a result of later Greek writers such as Plato and Polybius) Herodotus (5.92) on Periander of Corinth “At the beginning Periander was gentler than his father had been. But afterwards, when he had dealt, by messengers, with Thrasybulus, tyrant of Miletus, he became yet bloodier…For he sent a herald to Thrasybulus inquiring about the safest political establishment for administering the city the best. Thrasybulus led out Periander’s messenger, outside the city, and with him entered a sown field; then he walked through the field, questioning, and again questioning, the herald about his coming from Corinth. And ever and again as he saw one of the ears of grain growing above the rest he would strike it down, and what he struck down he threw away, until by this means he had destroyed all the fairest and strongest of the grain….Periander understood the act of Thrasybulus and grasped in his mind that what he was telling him was that he should murder the most eminent of the citizens.” “The Greeks remembered the rise and fall of their tyrants most diligently; they were far less interested in what tyrants did after their power was secure and before it began to waver. This focus expresses the Greeks’ own interests in tyranny, which, when its temporal limits were clearly defined, became a single coherent political event with a clear plot, characters, and a tangible moral lesson. But this focus also makes it very difficult to reconstruct tyranny in other terms than the Greeks did. From a perspective that rigorously distinguishes between the reality and the perception of tyranny, the memories of tyrants are, at their best, politically interested, biased, and partial; at their worst, they are incidental, sensational, and scandalous, full of the fascination tyrants held and virtually devoid of information about what they did. It is impossible to miss the significance of these gaps and biases, and no historian would hesitate to trade a story like Herodotus’s tragic account of Polycrates’ fall for information about the interactions between tyrants and aristocrats.” James F. McGlew, Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece Typology of Greek Tyranny Exile of Rival Aristocrats and Confiscation of Property Sending out of colonies; seeking sources of revenue abroad Engage in public works projects; beautification of polis Promotion of new civic festivals; fostering polis solidarity Break down patron-client hierarchies of the aristocracies; liberate the demos for future political participation New aristocracies of wealth as opposed to birth and aristocratic privilege (?) Periander of Corinth’s Diolkos Herodotus (3.60): Polycrates and Samos “I have talked…about the Samians, because, of all the Greeks, they have made the three greatest works of construction. One is a double-mouthed channel driven underground through a hill nine hundred feet high….The second is a mole in the sea around the harbor, one hundred and twenty feet deep. The length of the mole is a quarter of a mile. The third work of the Samians is the greatest temple that I have ever seen.” Causes of Greek Tyranny: Some Theories Monetization of Greece--advance of the rising commercial class against the old, landed aristocracies Hoplite Military Development? Herodotus (1.60) on Pisistratus’ Reestablishment at Athens “There was in the deme of Paeania a woman called Phya, and in stature she was but three fingers short of four cubits, and beautiful besides. They fitted her with full armor, put her in a chariot, arranged her pose so that she would appear at her most striking, and drove her into the city. They had sent heralds to run ahead of them, and these, when they arrived, spoke as they had been ordered, “Men of Athens, receive with good will Pisistratus, whom Athena herself, having honored him above all mankind, is bringing back from exile to her own Acropolis.” So the heralds went about, saying these things, and the word immediately spread through the demes that Athena was bringing Pisistratus back. The people in the city believed that this woman was the goddess herself and offered prayers to her, for all that she was only human, and they welcomed Pisistratus.” Athens at the End of the Pisistratids The Panathenaic Way Amphora Similar to Those Awarded as Prizes at the Panathenaic Games Aftermath of the Tyrants Constitutional Governments and Written Law Codes Submission of private disputes to thirdparty arbitration Written statutory law Earliest Greek Written Law Codes ca. 650 BCE in Cretan Dreros Law Code of Gortyn Discussion Question Compare and Contrast the Wanax or King of the Bronze-Age Palace-Centers and the Greek Tyrant of Archaic Period (ca. 650-510 BCE). What would you regard as the most significant historical parallels and differences?