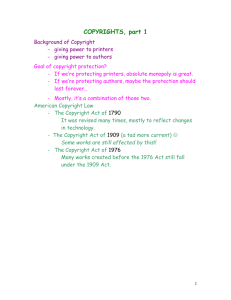

Copyright in the Research and Academic Environment

advertisement

Copyright in the Research and Academic Environment Janice T. Pilch University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign AAASS 40th National Convention Faculty Digital Resources Workshop Philadelphia November 20, 2008 Copyright in Research and Teaching • Creation and use of copyrighted works is essential to the educational and research activities of universities • Students and faculty create their own copyrighted works • Students and faculty use copyrighted works in teaching, research, and scholarship U.S. copyright law functions to maintain balance between rights of copyright holders and rights of people to use works. There are privileges and responsibilities on both sides. Steps in a Copyright Determination • Does a license restrict use of the work? • Is the work copyrighted in the U.S. today? Pre-1973 Soviet works may be under copyright in the U.S. today • Does the use correspond with one or more of the exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. law? • Is the planned activity covered by fair use, or by a library, educational or other limitation or exception in U.S. law? The basics of U.S. copyright law Copyright Act of 1976 (17 United States Code) http://www.copyright.gov/title17 • Requirements for copyright protection in U.S. – Originality – Minimal creativity – Fixation in tangible medium of expression • Copyright exists upon creation of the work – Since 1989 copyright notice no longer required in U.S. (© with year of first publication and name of copyright owner) • Jurisdiction of U.S. copyright law - Applies to U.S. works and eligible foreign works being used in the U.S. What is protected by copyright in U.S. Literary works Musical works, including any accompanying words Dramatic works, including any accompanying music Pantomimes and choreographic works Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works • Works of visual art Motion pictures and other audiovisual works Sound recordings Architectural works What is not protected by copyright in U.S. • Facts, ideas, procedures, processes, systems, methods of operation, concepts, principles, discoveries • U.S. federal government works • Works in public domain Who owns copyright in a work • Authors (initial authorship) • Employers in works made for hire (in some countries employees, as defined by law of country of origin) • Heirs or other special beneficiaries; transferees How international works can be copyrighted in U.S. • If work was first published in U.S. or after U.S. established copyright relations with country of origin,1 and it is still copyrighted • If on date of first publication, one or more of the authors was national or domiciliary of U.S. or a treaty party, or was a stateless person, and it is still copyrighted • If the work is a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work incorporated in a building or other structure, or an architectural work, located in U.S. or treaty party, and it is still copyrighted • If work is first published by United Nations or its specialized agencies, or by Organization of American States, and is still copyrighted • If the work comes within the scope of a Presidential proclamation (bilateral agreement), and is still copyrighted • If work was created/published at any time and copyright was restored under terms of Article 18 of Berne Convention and TRIPS Agreement2 Unpublished works are protected regardless of nationality or domicile of author. 17 U.S.C. §104 1Year when copyright relations established with U.S. • Albania 1994 • Armenia 1973 • Azerbaijan 1973 • Belarus 1973 • Bosnia and Herzegovina 1966 • Bulgaria 1975 • Croatia 1966 • Czech Republic 1927 • Estonia 1994 • Georgia 1973 • Hungary 1912 • Kazakhstan 1973 • Kyrgyzstan 1973 • Latvia 1995 • Lithuania 1994 • Macedonia 1966 • Moldova 1973 • Montenegro 1966 • Poland 1927 • Romania 1928 • Russia 1973 • Serbia 1966 • Slovakia 1927 • Slovenia 1966 • Tajikistan 1973 • Turkmenistan 1973 • Ukraine 1973 • Uzbekistan 1973 See U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 38a, International Copyright Relations of the United States http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ38a.pdf 2Copyright restoration On January 1, 1996, copyright was restored in U.S. to eligible foreign works which on that date had not yet fallen into the public domain in the country of origin through the expiry of the term of protection. For some countries the date of copyright restoration is later, in accordance with treaty obligations, as stipulated in Section 104a. • Consider date on which TRIPS Agreement became effective for U.S. with respect to copyright restoration for eligible works created or published in foreign countries • Works protected in the country of origin on that date were restored and are protected in the U.S. for the full U.S. term for a work created or published on that date • If work was not protected in the country of origin on that date, it is not currently protected in the U.S. • Works created or published after that date are protected in the U.S. for the full U.S. term Effective date of copyright restoration was January 1, 1996 for the following countries of origin: • Albania • Bosnia and Herzegovina • Bulgaria • Croatia • Czech Republic • Estonia • Georgia • Hungary • Latvia • Lithuania • Macedonia • Moldova • Montenegro • Poland • Romania • Russia • Serbia • Slovakia • Slovenia • Ukraine Effective date of copyright restoration for other nations: • Armenia--October 19, 2000 • Azerbaijan--June 4, 1999 • Belarus—December 12, 1997 • Kazakhstan—April 12, 1999 • Kyrgyzstan—December 20, 1998 • Tajikistan—March 9, 2000 • Uzbekistan—April 19, 2005 • Knowledge of national laws effective on January 1, 1996 or other effective date of copyright restoration is crucial • Works are restored for full U.S. term Exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. 1. Reproduction For example: quoting, photocopying, digitizing, printing, downloading, posting to a website 2. Preparing a derivative work For example: creating a translation, abridgement, annotated version, revised version, film based on book, drama based on novel, collage, musical arrangement 3. Public distribution For example: making a work publicly available on a website or other electronic forum where it can be copied Exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. 4. Public performance For example: showing a motion picture for a public audience, streaming a video to the public 5. Public display For example: Placing works on a website where they can be publicly viewed; publicly displaying still shots from a film; publicly displaying photographs 6. Public performance by means of a digital audio transmission For example: streaming a recorded song to the public [Section 106] Summary of U.S. copyright terms – If published before 1923, in public domain – If published with notice from 1923-1963 and renewed, 95 years from date of publication – If published with notice from 1964-1977, 95 years from date of publication – If created, but not published, before 1978, life of author + 70 years or 12/31/2002, whichever is greater – If created before 1978 and published between 1978 and 12/31/2002, life of author + 70 years or 12/31/2047, whichever is greater Summary of U.S. copyright terms – If created from 1978- , life of author + 70 years (for works of corporate authorship, works for hire, anonymous and pseudonymous works, the shorter of 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation) – If published without notice from 1/1/1978-3/1/1989 and registered within 5 years, or if published with notice in that period, life of author + 70 years (for works of corporate authorship, works for hire, anonymous and pseudonymous works, the shorter of 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation) * For U.S. works, registration and renewal records in U.S. Copyright Office will be relevant; for certain foreign works, this may also be relevant. Resources on copyright terms and status of works See charts by: • Laura Gasaway http://www.unc.edu/~unclng/public-d.htm • Peter Hirtle http://www.copyright.cornell.edu/training/Hirtle_Public_Domain.htm • Michael Brewer and ALA Office for Information Technology Policy http://www.librarycopyright.net/digitalslider • U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 22, How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ22.pdf • U.S. Copyright Office database of copyright records (Jan. 1, 1978- ) http://www.copyright.gov/records • Stanford Copyright Renewal Database (for books 1923-1963) http://collections.stanford.edu/copyrightrenewals/bin/page? forward=home Fair use Certain limitations and exceptions to copyright enable use of copyrighted works without prior permission of the copyright holder or payment of a royalty. Fair use is one of these. “Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include — Fair use (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.” [Section 107] Fair use • Establishes that certain uses are not infringing, depending on 4 factors, for purposes including criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, and research • Applies to all types of works, published and unpublished, and all formats (technology neutral) • Broad and ambiguous • But does not guarantee against infringement Weighs for fair use: • Purpose: Education, research, criticism, comment, news reporting, transformative use, parody, non-commercial use • Nature: Published, work of factual nature, informational, nonfictional • Amount: Small portion, non-essential portion • Effect: No major effect on market or potential market for work Weighs against fair use: • Purpose: Commercial use, entertainment, nontransformative use • Nature: Unpublished, highly creative work • Amount: Large portion, “heart” of the work • Effect on market: Affects market or potential market for work • See Checklist for Fair Use, in Kenneth D. Crews, Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies and Practical Solutions, 2d ed. (Chicago: American Library Association, 2006), 124. Fair use cases • Harper & Row, Inc. v. The Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985) About 300 words from an approx. 30,000-page manuscript. Not a fair use. • Salinger v. Random House, Inc., 811 F.2d 90 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 890 (1987) Large portions of unpublished letters by J.D. Salinger paraphrased by a biographer for publication in a book. Not a fair use. • Wright v. Warner Books, Inc., 953 F.2d 731 (2d Cir. 1991) Quotes from 6 unpublished letters and 10 unpublished journal entries, not more than 1% of Wright’s unpublished letters used in a scholarly biography. A fair use. • Sundeman v. The Seajay Society, Inc., 142 F.3d 194 (4th Cir. 1998) Scholar used quotations from an unpublished literary manuscript in research paper presented at academic conference. A fair use. Fair use cases • Penelope v. Brown, 792 F. Supp. 132 (D. Mass. 1992) Writer of manual for aspiring authors used examples of sentences taken from a book on English grammar and usage, in 5 pages of a 218-page book. A fair use. • Higgins v. Detroit Education Broadcasting Foundation, 4 F. Supp. 2d 701 (E.D. Mich. 1998) 45 seconds of a short song were used as background music in a television program broadcast on a PBS affiliate, which also sold copies of the program to educational institutions for educational use. A fair use. Transformative use was a factor. Sources: • Stanford Copyright and Fair Use website, http://fairuse.stanford.edu/Copyright_and_Fair_Use_Overview/ chapter9/index.html • Kenneth D. Crews, “Court Case Summaries,” http://www.copyright.columbia.edu/court-case-summaries Fair use: Using copyrighted works in research • Term papers, assignments, projects, classroom presentations, scholarly publications, other scholarly works • Theses and dissertations • Proquest UMI website: http://www.proquest.com/en-US/products/ dissertations • Institutional guidelines Fair use: Using copyrighted works in research • Reasonable, limited, educational, scholarly uses of materials are more likely to be fair use • Consider whether the use will involve print-only access, restricted Web access, or public Web access • Publication and digital distribution create more copyright considerations • Limit to amount needed to meet goals of research • Read publishers’ policies and guidelines carefully • Be familiar with UMI Proquest policies and guidelines for theses and dissertations • Always credit the source Using copyrighted works in face-to-face teaching • U.S. copyright law allows for performance and display of works in face-to-face teaching activities of nonprofit educational institutions – In a classroom or similar place devoted to instruction – Requires that when using a motion picture or other audiovisual work, the copy used must be lawfully made [Section 110(1)] • This enables presentation of copyrighted works, such as text, images, charts, tables, musical works, sound recordings, audiovisual works, in a live classroom Using copyrighted works in distance education: The TEACH Act • The law was revised by Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization (TEACH) Act of November 2002 to allow for use of works through digital networks in distance learning. [Section 110 (2)] – Permits performance of nondramatic literary or musical works (excerpts from books, journal articles, songs, etc.) – Permits “reasonable and limited portions of any other work” (paintings, charts, graphs; dramatic: operas, plays; audiovisual works, etc.) – Permits display of work in amount comparable to typical live classroom session – If teaching done by instructor as integral class session as part of “systematic mediated instructional activities” – If use is directly related to teaching content – If transmission is limited to students enrolled in course The TEACH Act: Institutional requirements – Applies to government bodies and accredited nonprofit educational institutions – Copyright policies must be in place – Institution must provide informational materials to faculty, students, staff to promote compliance with copyright law – Copyright notices must be placed on materials – Technical security measures must be made to prevent retention “beyond duration” of class session and unauthorized further dissemination – Interference with technological protection measures is not permitted The TEACH Act • Also: – Permits retention of content and student access for limited time, provided that no further copies are made – Permits reproduction and retention as necessary for technical purposes – Permits digitization of analog works for classroom teaching if amount is appropriate and if digital version not already available at the institution or if it is available but restricted by technological protection measures [Section 112] Distance education: options • Take advantage of the TEACH Act – Involves cooperation among instructors, administration, and systems specialists – Requires compliance with all requirements—all or nothing • Take advantage of fair use – If you cannot comply with all terms of TEACH Act – If institution does not offer means for implementing terms of TEACH Act • See Checklist for the TEACH Act, in Kenneth D. Crews, Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies and Practical Solutions, 2d ed. (Chicago: American Library Association, 2006), 126. Using copyrighted works in teaching • Reasonable, limited, isolated, non-repeating uses of materials are more likely to be fair use • Limit to amount needed to meet educational purpose • Key factors are brevity, spontaneity, cumulative effect • Always credit the source • The risks associated with digital access need to be considered in the fair use analysis • Handouts should not be a substitute for class reading materials or coursepacks, or for “consumable” workbooks—avoid multiple copies of different works that substitute for the purchase of works Academic coursepacks • Permissions should be obtained for copyrighted material in coursepacks • Generally it is the instructor’s responsibility to obtain permissions • Two key cases concerning academic coursepacks: • Basic Books, Inc. v. Kinko’s Graphics Corp., 758 F. Supp. 1522 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) Kinko’s copy shop photocopied copyrighted material from a book for an academic coursepack. Not a fair use. Not all educational uses qualify for fair use. This case changed the way that institutions deal with coursepacks. • Princeton Univ. v. Michigan Document Servs., 99 F.3d 1381 (6th Cir. 1996) Again, coursepack copying of copyrighted material. Not a fair use. Print and electronic reserves • Many institutions base their library reserve practices on fair use • Read institutional policies carefully • Chilling effect of recent lawsuits against universities Steps in determining whether to seek permission to use a work • Does a license restrict use of the work? • Is the work copyrighted in the U.S. today? • Does the use correspond with one or more of the exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. law? • Is the planned activity covered by fair use, or by a library, educational or other limitation or exception in U.S. law? The need to seek permission is more likely if: • The use is commercial • The use is repeated • The work is being used in its entirety and it is substantial Obtaining copyright permissions 1. Identify copyright holder • • • • 2. 3. Use copyright notice as a starting point Copyright holder might be author/multiple authors, publisher, heir or assignee/multiple heirs or assignees For published works, try the publisher Use any entity associated with author to track copyright holder Contact copyright holder directly --or— contact a collective rights organization to negotiate permissions Draft permissions letter • Include as much information as possible on planned use (what, where, when, why, how, how much) Obtaining copyright permissions 4. Negotiate permissions agreement, possibly involving fee 5. Obtain signed permissions agreement Lack of response does not substitute for permission More on collective rights organizations: • Copyright Clearance Center (CCC): http://www.copyright.com/ • University of Texas copyright website on Getting Permission: http://www.utsystem.edu/OGC/IntellectualProperty/ PERMISSN.HTM • Columbia University copyright website: http://www.copyright.columbia.edu/collectivelicensing-agencies • International Federation of Reproduction Rights Organizations: http://www.ifrro.org/show.aspx?pageid=home Thank you! Janice T. Pilch Associate Professor of Library Administration Head, Slavic and East European Acquisitions University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign E-mail: pilch@uiuc.edu