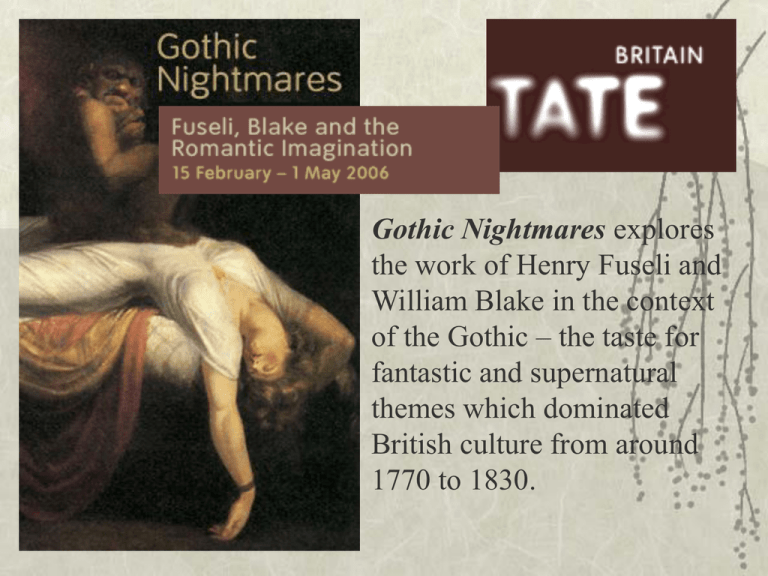

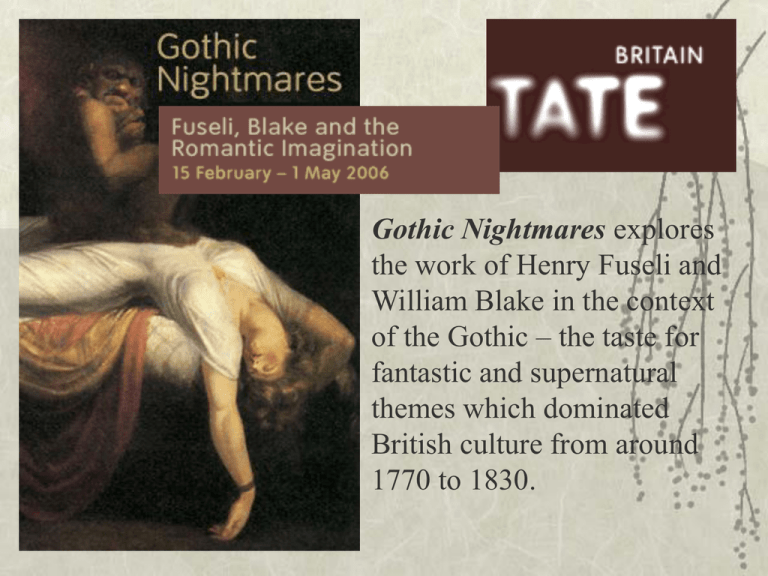

Gothic Nightmares explores

the work of Henry Fuseli and

William Blake in the context

of the Gothic – the taste for

fantastic and supernatural

themes which dominated

British culture from around

1770 to 1830.

Henry Fuseli

The Nightmare exhibited 1782

Oil on canvas, 1210 x 1473 x 89 mm

Lent by the Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase with funds from Mr and Mrs Bert L. Smokler and Mrs Lawrence A.

FleischmanThis painting created a sensation when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1782.

What is the subject of this painting? We may never be sure; Fuseli wanted his picture to intrigue

us. The leering imp may embody the physical effects of a nightmare, or be an emblem of sexual

desire. Is this picture an allegory, an illustration of a literary source, or something more personal?

William Blake

Plate 33 from Jerusalem

(copy 'A'), printed around 1820

Relief etching, uncoloured

© Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

This print shows the motif of The

Nightmare being stretched and

reinterpreted in the most radical and

complex way. It is from the original

‘illuminated’ version of Blake’s poem

Jerusalem. The lower scene shows

the female figure of Jerusalem laying

flat, with the ‘insane and most

deform’d’ Spectre evoked by the text

hovering over her.

Henry Fuseli, Prometheus 1770-1771

Pen and ink on paper, 150 x 222 mm

Lent by the Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett

This is an example of the results of the ‘five-point’ drawing games Fuseli and his friends engaged in

while in Rome The game involved placing dots in a random pattern on a sheet and joining these with

the head and extremities of a drawn figure. Some of these dots are still visible here. The essence of the

game was speed and facility, rather than plodding correctness.

Richard Cosway

Prometheus circa 1785-1800

Pen and brown ink on paper, 225 x184 mm

Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach

Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The

New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and

Tilden Foundations.

Thomas Banks

The Falling Titan 1786

Marble 838 x 902 x 584 mm

Lent by the Royal Academy of Arts, LondonCast from the heavens, a rebellious Titan crashes

through rocks while a tiny satyr and goat flee for their lives. According to classical mythology, the

giant Titans had sought to overthrow heaven but their revolution failed and they were hurled to

earth to make way for Zeus and his family. Banks was a close friend of Fuseli. Although this work

is highly refined in its execution, it shows their shared interest in strange and savage themes.

William Blake

The Punishment of The Thieves 1824-7

Chalk, pen and ink and watercolour on paper, 372 x 527 mm

This drawing represents the ‘Punishment of the Thieves’ that Dante and Virgil witness in the

eighth circle of Hell, described in Cantos 24 and 25 of Dante’s Inferno (1319-21). Here, punished

souls are attacked by snakes and transformed into monstrous serpents. Blake makes the most of

the possibilities for grotesque spectacle offered by the medieval poet.

Theodore Von Holst

Frontispiece to Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831

Steel engraving in book 93 x 71 mm

Private collection, Bath

This is the first illustrated edition of Mary

Shelley’s Frankenstein, originally published

in 1818. Von Holst’s design evokes the

heroic, heavy-limbed figures of Fuseli. The

setting, with its dramatic lighting and

medieval tracery, is thoroughly Gothic in

style.

Henry Fuseli

The Witches Show Macbeth the Descendants of Banquo (Die Hexen zeigen Macbeth Banquos Nachkommen) 1773/1779

Pen and wash on paper, 360 x 420 mm © 2006 Kunsthaus, Zürich. All rights reserved.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth is shown a vision of the future by the three witches: a procession of the eight

kings who will descend from his rival Banquo, the last holding up a mirror that throws light into

Macbeth’s eyes. This design was created in 1773 and reworked while the artist was briefly revisiting his

home town of Zürich in 1779. It was almost certainly a compositional study for a spectacular painting

(now lost) that Fuseli exhibited in London in 1777.

Henry Fuseli

Buoncante da Montefeltro circa 1774-1778

Pen and ink and wash 475 x 353 mm © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

Fuseli renders a scene of spiritual conflict from Dante’s Purgatory (1319- 21) as a grandiose physical

drama. Buonconte da Montefeltro was killed in battle in 1289, during Italy’s bloody civil wars. In

Dante’s account, good and evil angels vie for his body briefly, but his soul is saved because of one

final tear of repentance. This is the scene that Fuseli dramatizes

Henry Fuseli

Satan Starting from the Touch

of Ithuriel's Spear (Satan flieht, von

Ithuriels Speer beruht) 1779

Oil on canvas, 2305 x 2763 mm

Milton’s Satan, represented

here as a heroicallyproportioned figure, leaps

back from the slightest touch

of the angel Ithuriel’s spear.

He protects Adam and Eve,

who slumber in each other’s

arms at the bottom of the

composition. This canvas was

exhibited by Fuseli at the

Royal Academy in 1780. It was

one of the works which made

his reputation as a painter of

infernal subject-matter.

Him thus intent Ithuriel with his Spear

Touch’d lightly; for no falsehood can endure

Touch of Celestial temper, but returns

Of force to its own likeness: up he starts

Discoverd and surpriz’d. As when a spark

Lights on a heap of nitrous Powder, laid

Fit for the Tun some Magazin to store

Against a rumord Warr, the Smuttie graine

With sudden blaze diffus’d, inflames the Aire:

So started up in his own shape the Fiend. John Milton, Paradise Lost, 1667, Book IV, ll.810-19

James Barry

Satan and his Legions Hurling Defiance

Toward The Vault of Heaven circa 1792-1794

Etching,and engraving 746 x 504 mm

© Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

In a scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost

(1667), Satan and his troops, having been

expelled from Heaven for their rebellion,

glare back from Hell and rage against God.

Barry has used a low viewpoint and strong

tonal contrasts to emphasise the heroic

proportions of Satan. His rugged,

unconventional printmaking technique

enhances this characterization.

after Henry Fuseli

Satan Summoning his Legions,

engraved illustration to John

Milton, Paradise Lost published

by F.I. du Roveray 1802

Engraving in a bound volume 114 x 88 mm

Private collection, London

Satan has been expelled from

heaven, and here conjures up his

demonic army. This is one of six

small engravings executed after

designs by Fuseli, illustrating a

new edition of Milton’s Paradise

Lost (1667). Fuseli was all too

aware of the irony in seeing his

vast ambitions reduced to little

illustrations such as this.

Henry Fuseli

Macbeth Consulting the Vision of

the Armed Head 1793-1794

Oil on canvas, 1630 x 1300 mm

Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington

Shakespeare’s Macbeth has asked

the ‘Weird Sisters’ to predict

whether he will become king. The

apparition of an helmeted head

warns, ‘Macbeth! Macbeth!

Macbeth! Beware Macduff’,

referring to his political rival. Fuseli

noted that he had made the

features of the spectral head

resemble Macbeth’s own: would

not this make a powerful

impression on your mind?

“THUNDER. FIRST APPARITION:

AN ARMED HEAD.

MACBETH. Tell me, thou unknown

powerFIRST WITCH. He knows thy

thought: Hear his speech, but say

thou nought.

FIRST APPARITION. Macbeth!

Macbeth! Macbeth! Beware

Macduff, Beware the Thane of Fife.

Dismiss me. Enough.”

-William Shakespeare,

Macbeth (1606), Act 1, Scene 3

William Blake

Lear and Cordelia in Prison circa 1779

Pen and ink and watercolour on paper, 123 x 175 mm

Bequeathed by Miss Alice G.E. Carthew 1940

The ageing British king Lear lies sleeping on his daughter Cordelia’s lap while in prison. Lear’s

willfulness has split the kingdom, and Cordelia laments the fate of her father and of the nation. This is

one of a group of drawings by Blake dealing with British history made around 1779. His source for

this scene though was Nahum Tate’s reworking of Shakespeare’s King Lear (1681).

John British Dixon after Joshua Reynolds

Ugolino 1773

Mezzotint 505 x 615 mm © Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

This print reproduces Reynolds’ painting of the imprisonment of Count Ugolino de Gherardeschi

(d.1288), from Dante’s Inferno (1319-21). Thrown into prison after a political intrigue, Ugolino was left

to starve along with two of his sons and two grandchildren. The painting represents the moment

when he hears the door being permanently sealed, and he is suddenly awakened to his dreadful fate.

He will eventually commit a horrid act of cannibalism.

John Runciman

The Three Witches circa 1767-1768

Ink and body colour on prepared laid paper, 235 x 248 mm Lent by the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

This fluently-executed design probably shows the three witches from Shakespeare’s Mabceth

(1606), clustered together in wicked conspiracy. John Runciman made a profound impression on

his contemporaries during his short life. With his brother Alexander, he was among the first artists

to treat Shakespeare as the source of heroic subjects, presenting scenes and characters freed from

the trappings of stage presentations.

Alexander Runciman

The Witches show Macbeth The

Apparitions circa 1771-1772

Pen and brown ink over pencil on paper, 616 x 460 mm

Lent by the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

The tragic Scottish king Macbeth is

subjected to the alarming sight of the

three witches casting the spells that will

conjure prophetic visions. The drawing

seems to compress the images drawn by

the famous spell of the three witches ‘Double double toil and trouble’ – with

the culminating dance around the

cauldron: ‘Like elves and fairies in a

ring’.

Henry Fuseli

The Weird Sisters or The Three Witches 1783

In one of his best-known compositions,

Fuseli presents a dramatically stylized portrayal of the three witches from Shakespeare’s Macbeth

(1606). This painting was exhibited in 1783. A critic of the time commented: ‘He draws correctly, but

his Imagination, impetuous but not full, is the most incorrect Thing imaginable!’.

Oil on canvas, 650 x 915 mm Lent by the Kunsthaus, Zürich (gift of the city of Zürich)

BANQUO. What are

these So wither'd and

so wild in their

attire,That look not like

the inhabitants o' the

earth,And yet are on't?

Live you? or are you

aught That man may

question? You seem to

understand me, By

each at once her

choppy finger laying

Upon her skinny lips:

you should be women,

And yet your beards

forbid me to interpret

That you are so.

-William Shakespeare,

Macbeth (1606), Act 1,

scene 3

Robert Thew after Henry Fuseli

Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus and the Ghost Published 29 September 1796

Stipple engraving on paper, 500 x 635 mm © 2006 Kunsthaus, Zürich. All rights reserved.

In a moonlit scene at the castle of Elsinor, Hamlet breaks from

his friend Horatio’s hold and thrusts himself in the direction of

the mysterious apparition of his dead father. This engraving

was one of the painter’s most admired images.

William Blake

Hamlet and his Father's Ghost 1806

Pen and grey ink, and grey wash, with watercolour 307 x

185 mm

© Copyright the Trustees of The British Museum

This represents Hamlet meeting the

ghost of his father, in the scene of

Shakespeare’s play where the

apparition tells his son the gloomy

truth about the incestuous and horrid

plots surrounding him. While Blake

painted extended series of illustrations

of Dante and Milton, he represented

subjects from Shakespeare

infrequently. When he did, his designs,

as here, tended to take on a relatively

conventional format.

James Gillray

A Phantasmagoria – Scene – Conjuring-up

an Armed Skeleton 5 January 1803

image: 279 x 245 mm

With permission of the Warden and Scholars of New College,

Oxford

The three witches from Shakespeare’s

Macbeth (1606) are shown wearing the

features of contemporary opposition

politicians, including Charles James Fox.

The print criticises the Peace of Amiens

made with France in 1802, which was

perceived as sacrificing Britain’s interests.

The feigned oval suggests that the whole

scene may be a phantasmagorical

projection of the type popular at this time.

William Blake

The House of Death 1795/circa 1805

Colour print finished in ink and watercolour on paper, 485 x 610 mm

Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939 The

subject is taken from Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), Book X.

In a vision presented to Adam, Death hovers over a plague-house, dart in hand, teasing his

victims with the promise of eternal sleep but letting them suffer further.