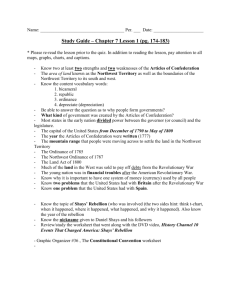

The Northwest Territory & Ordinance

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the Continental Congress in the United

States on May 20, 1785. Under the Articles of

Confederation, Congress did not have the power to raise money by direct taxation of the citizens of the United States. Therefore, the immediate goal of the ordinance was to raise money through the sale of land in the largely unmapped territory west of the original states acquired at the 1783 Treaty of

Paris, after the end of the Revolutionary War.

Thomas Jefferson was acutely aware of the great potential benefits offered by lands in the West. A growing population in the original states, now largely free from British interference, was beginning to push into these areas. Jefferson had earlier offered a systematic means to prepare new areas for statehood in his Ordinance of 1784. In the following year, he directed his attention to designing a system for surveying the lands that might avoid the pitfalls of earlier methods of determining boundaries.

Many landowners in the original states had become embroiled in ownership disputes because their property lines were defined in terms of rocks, streams and trees — any of which could disappear or be moved. Another nagging feature of the old system was that frugal purchasers would buy only the best pieces of land by carving out irregular plots that avoided undesirable wasteland. Early land ownership maps appeared to be jigsaw puzzles.

Jefferson’s proposal was much more orderly. He advocated the creation of a rectangular or rectilinear system of land survey. The basic unit of ownership was to be the township — a six-mile square or 36 square miles. (Jefferson had actually favored townships of 10-mile squares, but Congress believed those plots would be too large and difficult to sell.) Each township was to be divided into 36 sections, each a one-mile square or 640 acres.

A north-south line of townships was to be known as a range.

Borrowing from a New England practice, the Ordinance also provided that Section 16 in each township was to be reserved for the benefit of public education. All other sections were to be made available to the public at auction.

The Ordinance provided that sections be offered to the public at the minimum bidding price of one dollar per acre or a total of $640. Jefferson and other members of Congress hoped that competitive bidding would bring in receipts far in excess of the minimum amount. The meager treasury of the

Confederation sorely needed every dollar it could find.

The Ordinance of 1785 was landmark legislation. By preparing this means for selling Western lands, the government introduced a system that would remain the foundation of U.S. public land policy until the enactment of the Homestead Act of 1862. Modifications, however, would occur over the years as it became apparent that $640 was more than many could afford and, similarly, that 640 acres was too large for most family farms. Future legislation would keep the basic system intact, but reduce the minimum acreage requirement.

A revision of the statehood provisions for the

Northwest came in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

The Northwest Territory & Ordinance

1.

What current states made up the Northwest Territory?

2.

What was the purpose of the Northwest Ordinance of 1785?

3.

What was the primary problem with the way the Northwest Territory was being carved up prior to TJ’s Ordinance of 1785?

4.

Explain TJ’s proposal for organizing the new lands we gained by way of the Treaty of Paris.

5.

How did this system help create a universal public education system?

6.

Explain the system for auctioning off the lands not reserved by the government.

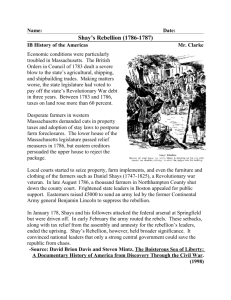

Shays' Rebellion was a post-Revolutionary clash between New England farmers and merchants that tested the precarious institutions of the new republic. The rebellion threatened to plunge the

"disunited states" into a civil war. The rebellion arose in Massachusetts in August 1786, spread to other states, and culminated in the rebels' march upon a federal arsenal. It wound down in 1787 with the election of a more popular Massachusetts governor, an economic upswing, and the creation of the Constitution of the United States in Philadelphia.

Historical Background

By the year 1786, the "disunited states" (as the Tories liked to call them) had achieved political independence – but the eastern states seemed on the verge of collapse as the flames of civil war menaced New England.

The American Revolution, it seemed, had almost gone too far. General George Washington wrote:

"I am mortified beyond expression when I view the clouds that have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned in any country... What a triumph for the advocates of despotism, to find that we are incapable of governing ourselves and that systems founded on the basis of equal liberty are merely ideal and fallacious."

Others in the political elite held the same opinion – even Massachusetts' onetime Revolutionary agitator, Samuel Adams:

"Rebellion against a king may be pardoned, or lightly punished, but the man who dares to rebel against the laws of a republic ought to suffer death."

Only the young Thomas Jefferson – reflecting more philosophically and from a safe distance in

Europe – disagreed:

"A little rebellion now and then is a good thing. It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government. God forbid that we should ever be twenty years without such a rebellion."

All eyes were on Massachusetts, where the insurgents who called themselves "Regulators" or

"Shays men" had brought about riots, raids, and the closing of courts.

New England's agrarian (farming) way of life, which furnished a social structure for the rural majority, was independent-minded, community-oriented and traditional in its economy and cultural values. New England's merchants and shippers, in contrast, had wide-ranging, dynamic business interests and more cosmopolitan

(untraditional) social relations.

Following the hardships of the Revolutionary War, this merchant class worked to put trans-Atlantic trade on a firm footing and also provided political leadership. Massachusetts' two leading traders,

James Bowdoin and John Hancock, held the Governor's office for the entire decade 1780-1791.

Economic Crisis: High taxes, mounting debt

In the first years of peacetime, the future of both the agrarian and commercial society appeared threatened by a strangling chain of debt, which aggravated the depressed economy of the postwar years. Many of the farmers were veterans who had trudged home from the Revolution "with not a single month's pay" in their pockets, but only government certificates they had long since sold away to speculators.

Adding to the farmers' postwar frustrations, heavy land taxes undermined the fragile financial structure of the hill towns. Farmers grew indignant as they watched the furniture, grain and livestock of their relatives and neighbors sold off for much less than their value. As they saw a brother, father or cousin haled to debtors' court, charged high legal fees, and threatened with prison, the farmers of western and central Massachusetts feared they would all lose their land and their homes.

At first the farmers attempted to work within the framework of government, seeking only to modify it and (from their viewpoint) improve it. But by the autumn of 1786 state lawmakers had issued only small or token reforms, and these came too late to pacify the farmers, who needed immediate relief. With debtors' court still a reality, it now seemed to the farmers that help lay only in open rebellion.

The leader of the movement was Daniel Shays, 39, a farmer who had served at the Battle of Lexington, been distinguished for his gallantry at the Battle of Bunker Hill and seen action at the crucial Battle of Saratoga in 1780.

Now, somewhat reluctantly, he was commanding insurgent actions at

Springfield, and before long the name of Captain Shays became a battle cry for as many as nine thousand rebellious farmers throughout the disaffected areas of New England.

Shays' followers had no uniforms except for the coats and hats that some had worn as Revolutionary soldiers. They identified themselves by wearing a sprig of hemlock (evergreen) in their hats. During the autumn of 1786, veterans like Shays organized groups of farmers into squads and companies in order to march upon the hated debtors' courts and force them to postpone their business.

Boston merchants and legislators viewed these court closings with rising fear for the very foundations of their society. In response to this alarm, the Congress of the Confederation authorized the raising of troops to combat the rebels, but the national government proved powerless to raise the financing. Finally, Massachusetts' governor James Bowdoin and other merchant leaders in

Massachusetts used their own funds to field an army.

Governor Bowdoin dispatched a militia financed by Boston merchants headed by former American

Revolutionary War General Benjamin Lincoln as well as the local militia of 900 men to protect the

Springfield court so that it could continue to process property confiscations.

The rebels were

dispersed in January 1787 with over 1,000 arrested. Bowdoin declared that Americans would descend into "a state of anarchy, confusion, and slavery" unless the rule of the law was upheld.

Significance:

Ultimately, the uprising was the climax of a series of events in the 1780s that convinced a powerful group of Americans that the national government needed to be stronger so that it could create uniform economic policies and protect property owners from infringements on their rights by local majorities. These ideas stemmed from the fear that a private liberty, such as the secure enjoyment of property rights, could be threatened by public liberty - unrestrained power in the hands of the people. James Madison addressed this concept by stating that "Liberty may be endangered by the abuses of liberty as well as the abuses of power."

In sum, the insurrection of Daniel Shays and his followers was one of the key factors leading to the

Constitutional Convention.

Shay’s Rebellion:

1.

Which two groups were at odds with one another in Massachusetts before the rebellion occurred?

2.

Why were farmers in a particularly difficult situation following the war? Give me 2 reasons.

3.

What buildings did farmers throughout Massachusetts march on?

4.

How did Shays’ Rebellion illustrate the weakness of the Articles of Confederation?