الشريحة 1 - Adventure Works

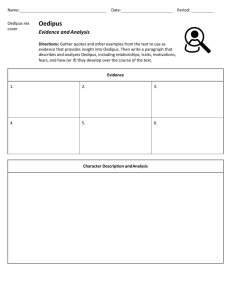

advertisement