The Flea

advertisement

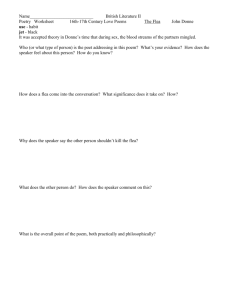

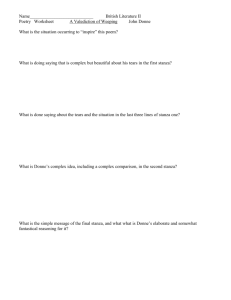

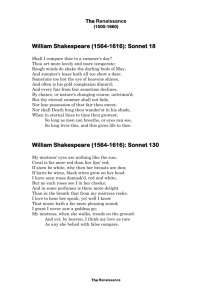

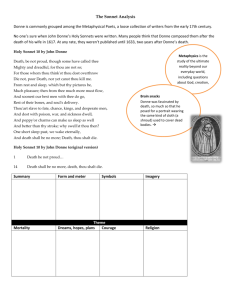

Unit 4 John Donne (1572-1631) Teacher:Michael Pang 庞开富 From※Suixi TVU John Donne • the leading figure of the metaphysical school John Donne was born to a prosperous London in 1572. His father died when he was young, and he was raised by his mother, Elizabeth. Donne's first literary work, satires was written during this period . This was followed by Songs and Sonnets. Then in 1617 Anne Donne died in giving birth to the couple's 12th child. Her death affected Donne greatly, though he continued to write, notably Holy Sonnets (1618). In his final years Donne's poems reflect an obsession with his own death, which came on March 31, 1631. John Donne is remembered for the wit and poignancy of his poetry. John Donne (1572?-1631) • Donne’s poems can be divided into two categories: the youthful love lyrics and the later sacred verses. The youthful love lyrics were published after his death as Songs and Sonnets in 1633. His early poems were love songs, elegies, and verse satires. • Donne’s later sacred verses, published in 1624 as Devotions upon Emergent Occasions which show the intense interest Donne took in the spectacle of morality under the shadow of death, a vision that haunted him perpetually, and inspired the highest flights of his eloquence. John Donne’s Poetry • Youthful love lyrics: Songs & Sonnets, 1633 1. different from most of the Elizabethan lyrics, cut wide from the path of courtly polish and restraint; 2. whimsical and satirical in mood and almost exclamatory in tone; 3. characterized by directness, irony and cynicism. 4. suffused with an emotional intensity and a spiritualized ardour unique in English poetry; 5. fantastic metaphors and extravagant hyperboles • Later sacred verses: Devotions upon Emergent Occasions in 1624 1. showed the intense interest Donne took in the spectacle of morality under the shadow of death. Metaphysical Poetry • The term applies to a group of 17th-century English poets who used certain common techniques and employed a few common themes. – – – – Revolt against Elizabethan love poetry and the tradition. Psychological analysis of emotions of love and religion. Penchant for novel and even shocking comparisons. Metaphysical conceit --- extended metaphor. • Metaphysical wit --- comparison of apparently quite dissimilar objects of concepts and the discovery that they are after all similar. – Roughness of meter and irregular rhyme. The Metaphysical School • Though there was no organized group of poets who imitated Donne, the influence of his poetic style was widely felt on George Herbert, Richard Crashow, Henry Vaughan, and A. Cowley. • They were named as the metaphysical school of poets by John Dryden and Dr. Johnson, not without a derogatory connotation. • Samuel Johnson coined the term "metaphysical poets" to describe Donne and his poetic descendants when he wrote of Abraham Cowley in the Lives of the English Poets that the metaphysical poets were men of learning, and to show learning was their whole endeavor. The Metaphysical School • The diction is simple, and echoes the words and cadences of common speech. • The imagery is drawn from the actual life. • The form is frequently that of an argument with the poet’s beloved, with god, or with himself. Donne’s Poetry --- Unmusicalness • It is due to Donne’s conversational tone and employment of natural speech rhythms; Donne’s poetry is famous for its abrupt, direct, surprising openings. Plainly the aim here is not sweetness, grace, or verbal melody. • It is a result from a vigorous exploitation of the natural rhythms of the speaking voice. Donne was a conscious artist, and he deliberately avoided conventional fluency of movement and courtliness of diction. • It adopts a diction and meter modeled on the rough giveand-take of actual speech. One of the prime causes of dissonant effects in Donne’s juxtaposing two or more stressed syllables. Unmusicalness Goe, and catche a falling starre, Get with child a mandrake roote, Tell me where all past yeares are, Or who cleft the Divels foot,... (Song) Busie old foole, unruly Sunne Why dost thou thus, Through windows, and through curtains call on us? ----The Sunne Rising Some more examples Stand still, and I will read to thee A lecture, Love, in loves philosophy. (A Lecture upon the Shadow) Come, Madam, come, all rest my powers defie, Until I labour, I in labour lie. (Going to Bed) Death be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for, thou art not soe,... (Holy Sonnets) Donne’s Poetry --- Verse argument • Admiration for difficulty in the thought. It puts to use a subtle and often outrageous logic. • It is usually organized in the dramatic or rhetorical form of an urgent or heated argument (first drawing in the reader and then launching the argument). • It reveals a persistent wittiness, making use of paradox, puns, and startling parallels. • Donne’s poetry is remarkable for its fusion of passionate feeling and logical argument. The more he was moved, the quicker his mind worked. Conceit (奇喻) • Or far-fetched comparisons. A comparison becomes a conceit when we are made to concede likeness while being strongly conscious of unlikeness. • The Elizabethan poets were fond of Petrarchan conceits, which were conventional comparisons, imitated from the love songs of Petrarch, in which the beloved was compared to a flower, a garden, or the like. • The metaphysical poets fashioned conceits that were witty, complex, intellectual, and often startling. • Samuel Johnson disapproved of such strained metaphors, declaring that in the conceit “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.” The Flea • Fleas were a popular subject for humorous and amatory poetry in all countries at the Renaissance. • Their popularity stems from an event that happened in a literary salon. The salon was run by two ladies, and on an occasion a flea happened to land upon one lady's breast. The poets were amazed at the creature's audacity, and were inspired to write poetry about the beast. It soon became fashionable among poets to write poems about fleas. Stanza 1 • • • • Marke but this flea, and marke in this, How little that which thou deny'st me is; Me it suck'd first, and now sucks thee, And in this flea our two bloods mingled bee; • • • • 光看看这只跳蚤,看看在它体内, 你拒绝我的东西是多么微乎其微; 我,它先叮咬了,现在又叮咬你, 在这跳蚤肚里,我俩的血混为一体; Stanza 1 • • • • • Confesse it, this cannot be said A sinne, or shame, or losse of maidenhead, Yet this enjoyes before it wooe, And pamper'd swells with one blood made of two, And this, alas, is more than wee would doe. • • • • • 坦白承认此事,这并不能够说 是一桩罪过,或耻辱,或丧失贞洁, 可是这家伙不经求爱便享用, 腹中饱胀两人的血混成的一种, 而这,咳,比我们要做的还深重。 The Flea 1st stanza: Contemplative and whimsical • In this poem, the "I" of the poem is lying in bed with his lover, and trying to get her to give her virginity to him. While lying there, he notices a flea, which has obviously bitten them both. Since the 17-century idea was of sex as a "mingling of the blood", he realizes that by mixing their bloods together in its body, the flea has done what she didn't dare to do. • Then, he argues, since the flea has done it, why shouldn't they? To back up his argument, he refers to the marriage ceremony, which states that "Man shall be joined unto his wife and they two shall be one flesh". He argues that since they have mingled their bloods and are therefore "one blood", they are practically "one flesh" and are therefore married! Stanza 2 • • • • Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare, When we almost, nay more than maryed are. This flea is you and I, and this Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is; • • • • 呆着吧,三个生命共存在一只跳蚤里, 在其中我们几乎,不,更甚于婚配。 这跳蚤就是你和我,它的腹腔 就是我们的婚床,和婚庆礼堂; Stanza 2 • • • • • Though parents grudge, and you, w'are met, And cloysterd in these living walls of Jet. Though use make thee apt to kill me, Let not to this, selfe murder added bee, And sacrilege, three sinnes in killing three. • • • • • 尽管父母怨恨,你也不从,我们照样相会 且隐居在这活生生墨玉般的四壁之内。 虽说出于习惯你总是想扑杀我, 可是,别再给这加上自我毁灭 和渎圣——杀害三命的三重罪孽。 The Flea 2nd stanza: Becomes more absurd, pace gets faster • Not only does that reinforce his seduction argument, but it also provides ammunition for him to defend himself when the female does the next logical thing and moves to kill the flea. Donne argues that by spilling his blood and hers by killing the flea, she is practically committing murder. Not only that, but by breaking the holy bond of marriage she is committing sacrilege! • The flea becomes ultimately a symbol of the world in which the lovers' desires are realized, "this our marriage bed and marriage temple is." • Marriage and consummation is a past issue, since within the flea their blood is already mingled and the "child" of their union grows. • The flea is now the realm of marriage, all-encompassing the lovers and excluding any parents or patriarchal sanction. • The walls of this realm are jet black, indicating that something sinister or evil is to occur here. This could be a reference to the illicit marriage, or the forbidden mixing of royal and common blood, or perhaps only the impiety of the poet's comparison that loss of innocence should be so trivial as the life of a flea. • The lady's significance is reduced to that of a black widow spider at this point, where the poet says she is apt to kill him after this consummation of a non-existent marriage. • With this metaphor of the spider, who is also jet in color, the object of the man's love is reduced to the position of the flea. If the flea is pregnant with their blood-child, then she (the lady) may as well be pregnant too. • Now that this tie has been established between the blood of the woman and the flea, if the woman were to kill the flea, it would be a form of suicide. So to kill this flea, the woman would have to commit murder (of the symbolic marriage realm and the child within), suicide (killing of her own blood), and sacrilege (which suicide is). • Apparently the woman kills the flea anyway, since the death of the flea and her own corruption is addressed next. Stanza 3 • • • • Cruell and sodaine, has thou since Purpled thy naile, in blood of innocence? In what could this flea guilty bee, Except in that drop which it suckt from thee? • • • • 残忍而突然,你是否从此时此刻 染红了你的指甲,以无辜的鲜血? 这跳蚤有什么可以责难罪咎, 除了它从你身上吸取的那一小口? Stanza 3 • • • • • Yet thou triumph'st, and saist that thou Find'st not thyself, nor mee the weaker now; 'Tis true, then learne how false, feares bee; Just so much honor, when thou yeeld'st to mee, Will wast, as this flea's death tooke life from thee. • • • • 然而, 你得意洋洋,声称说 并未觉得自己,也没发现我变衰弱; 的确,那么该知道恐惧是多么虚幻不真; 当你委身于我时,将仅仅有那么点童贞 • 会损耗,一如这跳蚤之死从你那儿窃取的生命。 The Flea 3rd Stanza: Slowing and Reversal of Argument • However, the flea finally is killed, and the poet is forced to change tactics. There, he argues, killing the flea was easy, and as you say it hasn't harmed us - well, yielding to me will be just as easy and painless. • By killing the flea whom the poet has given such strange attributes, the woman squashes the symbolic world the man has constructed and brought them both back to reality. • By murdering the "innocent" flea, the lady has "purpled her nail," a color assigned to the clothing of royalty. She has committed the sins that destroy the union of their blood, so she triumphs. The Flea • She says that neither of them are any worse for the loss of blood caused by the pest, which the poet confirms to be the truth. • This comment suggests that the lady has just admitted her loss of innocence by implying that the flea really didn't do anything to deserve death. • The poet finalizes his argument for his cause by granting that the death of the flea is really of no consequence, as are her fears for her honor. Her honor will not waste when she gives in to him. • Upon her smashing of his poetic world of marriage and love, the man assures her that what she has done is of no consequence. He compares her fear for her honor to the importance of the now dead flea, which is nothing. The Flea • The poet asks his mistress to notice only this flea, to forget everything else as he delivers his argument. The flea has bitten them both, and their bloods mix within its body. • This mixing of bloods is somewhat of an insult to the lady, if she is of royal blood and he is not. The description of the swelling of the insect with "one blood made of two" is suggestive of surrogate pregnancy, a perversion of motherhood. • Such an allusion is definitely not a pleasant nor natural one, and it would be natural for the lady to kill the flea out of disgust after hearing these lines. The word "suck" in this context would be equivalent to the experience of passion or lust, which leads to the loss of innocence. • The man admits that the flea sucked him first, so he has lost his innocence, but he still finds himself honorable, so here he bases his own point of view. The Flea - analysis • Note the role of the female in this poem - her objections are never noted, just reacted to, and she makes the most powerful statement in the poem, yet it is a non-verbal statement (her crushing of the flea) • There is a lot of hyperbole in this poem, a technique that Donne often uses to make a point. – One blood made of two... - in Donne's time, the sex act was thought to be a "mingling of the bloods" - so the line is both lewd and playful, especially as it is followed by the teasing And this, alas, is more than wee would doe. – Purpled thy naile... - purple was a very expensive colour, associated with royalty and romance. Also note that in the first two lines of this stanza Donne is arguing that the death of the flea is more important than the loss of virginity. The Flea • This funny little poem is a speech delivered by a would-be lover to a reluctant lady, and the careful reader can discern her actions (and reactions) to his supplications. • This poem uses the image of a flea that has just bitten the speaker and his beloved to sketch an amusing conflict over whether the two will engage in premarital sex. • It exhibits Donne's metaphysical love-poem mode, his aptitude for turning even the least likely images into elaborate symbols of love and romance. • It is the cleverest of a long line of 16th-century love poems using the flea as an erotic image. Donne's poise of hinting at the erotic without ever explicitly referring to sex, while at the same time leaving no doubt as to exactly what he means, is as much a source of the poem's humor as the silly image of the flea is. • 元代赵孟頫,精绘画,擅书法,能诗文。他的妻子管道昇, 是一位贤良多才的女性,善画墨竹、兰、梅,亦工山水、 佛像,诗词歌赋也造诣很深,本来是女子中的佼佼者。但 赵孟不满足,异想天开地要纳妾,可又不便开口直言,便 填了一首词给夫人看,词中说:“岂不闻王学士有桃叶、 桃根,苏学士有朝云、暮云?我便多娶几个吴姬、越女无 过分。”同时,还安慰她:“你年纪已过四旬,只管占住玉 堂春。” 管道升的《我侬词》 • 你侬我侬,忒煞情多;情多处,热如火:把一 块泥,捻一个你,塑一个我。将咱两个一齐打 破,用水调和;再捻一个你,再塑一个我。我 泥中有你,你泥中有我:我与你生同一个衾, 死同一个椁。 A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning 别离辞:节哀 • Form: Each four-line stanza is quite unadorned, with an ABAB rhyme scheme and an iambic tetrameter meter. • Mood: direct statement of his ideal of spiritual love. • Theme: Anticipating a physical separation from his beloved, the speaker invokes the nature of that spiritual love to ward off the "tear-floods" and "sigh-tempests". • Main conceit: parallels between the continuing relationship of his persona's soul with that of his beloved's (despite their physical parting) and the coordinated movements of the two feet of a compass. A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning • The tone of the title: both the colon and the term "forbidding" in the context of mourning sound impersonal, authoritarian, and austere, like a decree, or a piece of academic writing, or lecture room demonstration. • This poem is frequently said to celebrate reticence, restraint, the withholding of shows of emotion at a temporary separation of the lovers; this suggests a sense of superiority over "dull, sublunary lovers," an "us vs them" mentality common in Donne. • The more current view is that the speaker is not as self-assured as he would wish to seem; that he seeks consolation (for himself and the woman) for fears of death on the trip and separation by the trip. His definition of the spiritual qualities of love never quite dispels his disquiet nor eases the pain of parting; consequently, the poem illustrates the failure of intellection to meet his emotional needs. • Hence, he tries several images, makes several attempts to redefine things and to arrive at a consolation that works. These main images are: A) dying man, B) beaten gold, C) stiff twin compasses. Quatrain 1 & 2 • As virtuous men pass mildly away, /And whisper to their souls to go, / Whilst some of their sad friends do say / The breath goes now, and some say, No; /So let us melt, and make no noise, / No tear-floods nor sigh-tempests move; / 'Twere profanation of our joys / To tell the laity ourimage love. The of a dying man reverses the Petrarchan convention that of lovers is like death: Petrarchan lovers have noisy, teary •separation 正如德高人逝世很安然, / 对灵魂轻轻的说一声走,/ 悲伤的朋友们 聚在旁边,/ 有的说断气了,有的说没有。/ separations because the lover fears that love will让我们化了,一声也不 vanish during his 作,/泪浪也不翻,叹风也不兴;/那是亵渎我们的欢乐—— /要是对 absence, that the woman 俗人讲我们的爱情 。 will find a new guy. These lovers, being "virtuous" will have a quiet parting; but the image gets out of the •speaker’s Main Idea: a metaphysical comparison between virtuous control, since perfect happiness for the soul ultimately dyingupon menseparation whispering to leave for their bodies depends fromto thetheir body,souls while happiness lovers and two lovers saying goodbye before journey depends on their being together (if the image wereaexact, the lovers would not want to reunite or even be able to!). Romeo and Juliet Act 3, Scene 5 • CAPULET: In one little body Thou counterfeit'st a bark, a sea, a wind; For still thy eyes, which I may call the sea, Do ebb and flow with tears; the bark thy body is, Sailing in this salt flood; the winds, thy sighs; Who, raging with thy tears, and they with them, Without a sudden calm, will overset • 你这小小的身体里面,也有船,也有海,也有风;因为 你的眼睛就是海,永远有泪潮在那儿涨退;你的身体是 一艘船,在这泪海上面航行;你的叹息是海上的狂 风…… Quatrain 3 • Moving of the earth brings harm and fears: Men recon what it did and meant; But trepidation of the spheres, Though greater far, is innocent. • 地动会带来灾害和惊恐, 人们估计它干什么,要怎样 可是那些天体的震动, 虽然大得多,什么也不伤。 The Ptolemaic Universe 托勒密的 宇宙图 Quatrain 4 • Dull sublunary lovers' love (Whose soul is sense) cannot admit Absence, because it doth remove Those things which elemented it. • 世俗的男女彼此的相好, (他们的灵魂是感官)就最忌 别离,因为那就会取消 组成爱恋的那一套东西。 Dull sublunary lovers' love/ (Whose soul is sense) cannot admit / Absence. • Sublunary: literally beneath the moon. In the Ptolemaic universe, those things underneath the sphere of the moon are fallen. So sublunary lovers are those whose love is imperfect or fallen. • Soul is sense: The anatomy of the soul, which contends that there are three levels of the soul: vegetable, sensible, and rational. Those who engage in fallen love are dependent upon the senses to express and experience love; spiritual love would be located in the rational soul. Quatrain 5 • But we, by a love so much refined That ourselves know not what it is, Inter-assured of the mind Care less eyes, lips, and hands to miss. • 我们被爱情提炼 得纯净, 自己都不知道存什么 念头 互相在心灵上得到了 保证, 再不愁碰不到眼睛、 嘴和手。 Quatrain 6 • Our two souls, therefore, which are one, Though I must go, endure not yet A breach, but an expansion, Like gold to airy thinness beat. • 两个灵 The image of a dying man does not work well, so the speaker 魂打成了一片, tries another image here: viewing parting not as a breach but an 虽说我 expansion of their souls, like gold to airy thinness beat. Problems 得走,却并不变成 here too: 1) makes parting sound like a positively good 破裂, thing; 2) the beaten gold expands without an actual increase in substance, 而只是向外伸延, but with an increase in fragility; 3) again, the image does not 像金子 suggest the eventual reunion of the lovers. 打到薄薄的一层。 Quatrain 7 • If they be two, they are two so As stiff twin compasses are two Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show To move, but doth if the other do. • 就还算两个吧,两个却 这样 和一副两脚规情况相同; 你的灵魂是定脚.并不 像 The Compass • the perfect image to encapsulate the values of Donne's spiritual love: balanced, symmetrical, intellectual, serious, & beautiful in its polished simplicity. • the twin legs of a compass = the lovers' sense of union during absence • the poet must then proceed to persuade the reader that these things are alike in spite of their apparent differences. Quatrain 8 • And though it in the center sit, Yet when the other far doth roam, It leans and hearkens after it, And grows erect, as that comes home. • 虽然它一直是坐在中心, 可是另一个去天涯海角, 它就侧了身.倾听八垠; 那一个一回家,它马上挺腰。 • Meaning: The lover who stays behind is the fixed point, and the speaker is the other leg of the instrument. The Last Quatrain • Such wilt thou be to me, who must, Like th’ other foot, obliquely run; Thy firmness make my circle just, And makes me end where I begun. • The last image 你对我就会这样子,我一生 of the stiff twin compasses works the best 像另外那一脚,得侧身打转; since it covers the separation, the continuous spiritual link (i.e., the mysterious "we two你坚定,我的圆圈才会准, are really one" phenomenon 我才会终结在开始的地点。 of love), and the return. N.B. the figure described is a spiral, (circular [immortal] • united Meaning: Without the "firmness" of the fixed point, he would be with linear [mortal] motions; "roaming" does not suit unable toacomplete drawing circle). the journey and make the “circle just” (the precise, perfect circle). • Throughout the poem, disturbances appear on the calm surface of his language, revealing that his own true emotions are suppressed only with difficulty, that there is a strong undercurrent of physical yearning for the woman: sad friends (3); melt (5); eyes, lips, hands, (20); roam (30); leans and hearkens (31); grows erect, home (32)-very physical terms that remind us of their whole beings (including bodies). • Even in the most successful image, the compasses, the posture of the legs reflects both the spiritual constancy of the lovers and their physical separation. At the end of the poem, everything depends upon her fidelity (firmness, 35), so the suppressed fear of losing her comes to the surface; indeed it is built into the conceit itself. • Thus, the poem expresses, rather than conquers, the pain of parting. Death be not proud 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou are not so; For those whom you think’st thou dost overthrow Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure, then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery. Thou’rt slave to Fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poision, war, and sickness dwell, And poppy, or charms can make us sleep as well, And better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally, And Death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die. a b b a a b b a c d d c e e • Death be not proud, though some have called thee • Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; • 死神別驕傲,雖然有些人稱呼你 • 偉大兼可怖,其實你未必是如此 1.personification: death • For those whom thou think thou do overthrow Die not, poor death, nor yet canst thou kill me. • 那些你以為將他們顛覆的人, • 其實並沒有死,死神,我也尚未被你殺死 • From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure, then from thee much more must flow, • 你所描繪的休息跟睡眠,其實是幸福, • 甚至從你那兒流露還更多 1. metaphor : sleep, pleasure • Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery, • 讓他們的骸骨得以安息,靈魂得以付託 • soonest our best men with thee do go, • 難怪即使是優秀的人也迫不及待跟你去 • Thou art slave to fate, chance, king and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell, • 你是命運、意外、國王、及絕望者的皂隸 • 與毒藥、戰爭、疾病狼狽為奸 1. irony; 2. metaphor : slave • And poppy, or charm can make us sleep as well, • and better than thy stroke; why swell’st thou then? • 罌粟嗎啡或符咒也照樣能使我們安息, • 而且比你的侵襲還要好。你又得意什麼? • One short sleep past, we wake eternally • 經過短暫的睡眠之後,我們就永遠清醒 1. respond: Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery • And Death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die. • • 死亡將不再存在, 死神,你死矣! 1. irony 2. paradox 3. respond : Death be not proud Comments • Some critics argue that Donne's speaker is trying to convince himself that death is not to be feared, and failing dismally; rest and sleep, which butdo thynot pictures be, • •From The poems various arguments at all address the •Much pleasure, then from thee much more must flow, speaker's basic fears. – E.g., he argues on flimsy evidence that death must be better than sleep (5-6), then that sleep is better than •Death, thou shalt die! death (11-12). – The 4 words of the poem, which crown Andlast poppy, or charms can make us should sleep as well, the argument, undermine it: ifswell’st death is nothing And betteractually than thy stroke; why thou then?to be afraid of, the speaker can hardly use it as a threat. Comments cont. • John Carey notes, "He stamps his foot with fine dramatic conclusiveness, and plummets straight through a trapdoor. It spoils the act, but improves the poem, for it shows how little its reasonings have impinged on the speaker's basic fears.“ • Carey's insight into this poem is generalized by R.T Jones: it is frequently claimed that Donne's poetry shows a complete union of thought and feeling, but Jones argues that what we usually get is the exact opposite, a sense of conflict or tension between what the heart wants to be true or fears to be true and what the mind knows or can argue; a sense of the poet always trying to convince himself of something. We noted this possibility in A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning. Comments cont. • Jones cites D.H. Lawrence's statement that belief is a profound emotion that has the mind's connivance. • Given his academic training, Donne must have known how bad the arguments are; so their very badness must be taken as part of the meaning of the poem. • If we accept that when Fate overwhelms you with a flood or chance directs lightening to your head, or a king has your head cut off or a desperate man cuts your throat, then death has no choice but to come to you (and hence is a slave to these things) then perhaps we will be less scared of Death as an abstraction, whatever that may mean, but simply transfer our terror, undiminished, to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men-leaving our predicament, if anything, somewhat worse. Comments cont. • But we would not be thinking in terms of terror at all if we had taken seriously the earlier arguments, e.g., "from rest and sleep"- we don't take this seriously because – a) we do not really accept that the relation between death and sleep is in all important respects the same as the relation between a picture and the thing depicted; – b) we cannot really believe that if a picture gives us pleasure the thing it depicts. 快樂的死者 波特萊爾 在爬滿蝸牛的沃土上 我要親自挖一個深坑 容我悠閒地舒展老骨頭 且長眠於遺忘中,一如浪裡白鯊 我憎恨遺囑,也憎恨墳塋 與其像世人乞討眼淚活著 我寧可邀請烏鴉 允乾每一處骯髒軀殼 蛆蟲啊! 無眼無耳的黑色伴侶 瞧! 自由快樂的蛆蟲走向你們 享樂的哲學家,腐敗的子孫 無須愧疚地穿行我的殘骸 並告訴我,死者中,這具 以亡的無魂老朽是否痛苦 Devotions upon emergent Occasions XVII • PERCHANCE he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill, as that he knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so much better than I am, as that they who are about me, and see my state, may have caused •她给婴儿施洗,这一行动也和我有关,因为婴 it to toll for me, and I know not that. 儿通过受洗就和一个躯体(指教会)发生联系, •而这躯体也是我的头,她嫁接到这躯体上,而 The church is Catholic, universal, so are all her actions; 这钟声是为某个人敲的,也许这个人已经病得很厉害, 我也是这躯体的一肢。 all that他已不知道这是为他敲的了;也许我自以为病情不象 she does belongs to all. 实际那样严重,而我周围的人看到我的实际情况也许 教会是无所不包、普及一切的,教 • When就叫人先去为我敲丧钟,我自己却还不知道那是为我 she baptizes a child, that action concerns me; for 会的行动也如此,她所做的一切属 that child is thereby connected to that body which is my 敲的。 于一切人。 head too, and ingrafted into that body whereof I am a member. • And when she buries a man, that action concerns me: all •上帝使用着不同的翻译人,有的文章由老年来译,有 mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one 的用疾病译,有的用战争,有的用法律;但每次翻译都 man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but 有上帝插手,上帝的手还将把我们散落的书页再次订起 translated into a better language; and every chapter must 来,放进那图书馆,在那里每部书都将是打开的,彼此 be so translated; 看得见。 教会埋葬一个人的时候,这一行动也和我有 关。全人类都由一个主所创造,是一本书, • God employs several translators; some pieces are 一个人死了,不等于从书里扯掉一章,而是 translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some 翻译成更好的语言;每一章都要这样翻译。 by justice; but God's hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another. • No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. •没有谁是个独立的岛屿;每个人都是大陆的一片土, 整体的一部分。大海如把一个土块冲走,欧洲就小了 一块,就象海岬缺了一块,就象你朋友或你自己的田 庄缺了一块一样。每个人的死等于减去了我的一部分, 因为我是包括在人类之中的,因此不必派人打听丧钟 为谁而敲;它是为你而敲的。 Song: Go and catch a falling star Song • This poem chiefly concerns the lack of constancy in women. • The tone taken is one of gentle cynicism, and mocking. • Donne asks the reader to do the impossible, which he compares with finding a constant woman, thus insinuating that such a woman does not exist. • The title, "Song", leads us to expect certain things: a lyrical element to the words, and a musical rhythm, which are fulfilled by this neatly crafted poem. It is also very ambiguous, not hinting at the subject matter of the poem. • The stanzas are slightly longer than might be expected, nine lines each, but this allows for the more complex and abstract ideas, which are archetypal of metaphysical poetry. The 1st stanza is the most forceful,1 employing the Stanza imperative to achieve a sense of command, and implying that Go and catch a falling star, he is talking to one specific Get with child a mandrake root, person. Tell me where all past years are, Or who cleft the Devil's foot, Teach me to hear mermaids' singing, • 去吧,跑去抓一颗流星, 去叫何首乌肚子里也有喜, Or to keep off envy's stinging, 告诉我哪儿追流年的踪影, And find 是谁开豁了魔鬼的双蹄, What wind Serves to advance an honest mind. 教我听得见美人鱼唱歌, 压得住醋海,不叫它兴波, 寻寻看 哪一番 好风会顺水把真心推向前。 Stanza 1 Analysis • The 1st sentence is a command: "Go and catch a falling star", and an impossible one, for how can one catch a star? The word "falling" suggests a gradual deterioration, rather than fallen which would be irretrievable, there is a sense that there is a chance, but it is narrow. • It is interesting that Donne is using the conventionally romantic image of a star in defiance of such a traditional idea as monogamy. It could also be linked to the fourth line which references the devil, as Lucifer was a fallen angel, and the stars are often symbolic of Angels and heaven, this devil imagery perhaps is an early suggestion of the duplicity of women. Stanza 1 Analysis cont. • Donne builds on this idea of the impossible in the second line, "Get with child a mandrake root", there is much superstition surrounding the mandrake plant, it is said to scream when pulled from the ground, and it "resembles the human form, sometimes the female form and sometimes the male, according to whether the roots are twofold or threefold". • This could again be linked to the devil who has "cleft" feet, which also resemble the fork-rooted plant through the idea of division and multiplicity. This in turn is suggestive of the inconstancy of women, suggesting their doubled relationships. Stanza 1 Analysis cont. • Further fantastical imagery is that of the "mermaids singing". Mermaids could be seen as important in this poem as they appear to be women above the waist but are not beneath, and this could therefore suggest that women can be deceptive creatures. • There is also the idea of them luring men to a watery death, it has been said that this links to the experience of Odysseus in "The Odyssey", although he encountered the sirens who dwelt on an island, not in the sea. Stanza 1 Analysis cont. • Donne uses the word "stinging" to describe envy, finally coming to the point of the poem overtly. The word sting suggests something, which is inflicted by some external force, it shifts any blame away from the subject of the envy. It is a piquant image, suggesting intensity of feeling. • There is also a slightly bitter undertone caused by the constant use of hard consonants such as "go", "get", "teach" and "tell". • Then the poem seems to slow down very quickly in the final refrain, seeming to echo the sound of the wind, the speaker wonders how honesty can be gained, and we can presume that this refers to honesty in the sense of being chaste. • It is necessary to point out that although "wind" does not seem as if it should rhyme with "find" and "mind", it was pronounced as such at the time, as is often seen in Shakespeare. In fact it was rather a familiar rhyme to use, quite boring in fact, which combined with the monosyllabic beat of these last few lines, seems to mirror his boredom with women. Stanza 1 Go and catch a falling star, Get with child a mandrake root, Tell me where all past years are, Or who cleft the Devil's foot, Teach me to hear mermaids' singing, • 去吧,跑去抓一颗流星, 去叫何首乌肚子里也有喜, Or to keep off envy's stinging, 告诉我哪儿追流年的踪影, And find 是谁开豁了魔鬼的双蹄, What wind Serves to advance an honest mind. 教我听得见美人鱼唱歌, 压得住醋海,不叫它兴波, 寻寻看 哪一番 好风会顺水把真心推向前。 Stanza 2The 2nd stanza is full of convoluted images and hyperbole; it is as if Donne is mocking the idea of a love poem in itself. • If thou beest born to strange sights, Things invisible to see, Ride ten thousand days and nights, Till age snow white hairs on thee, Thou, when thou return'st, wilt tell me All strange wonders that befell thee, And swear • 如果你生来有异禀,看得见 No where 人家不能看见的花样, Lives a woman true, and fair. 你就骑马一万夜一万天, 直跑到满头顶盖雪披霜, 你回来会滔滔不绝的讲述 你所遭遇的奇怪事物, 到最后 却赌咒 说美人而忠心,世界上可没有。 Stanza 2 Analysis • "Ride ten thousand days and nights, / Till age snow white hairs on thee" seems to echo the professions of love made by the other poets of his time, and yet he is using these images against the idea of love and monogamy. • It’s interesting Donne takes the commonly used hyphenated adjective of "snow-white" and uses it as a subjunctive verb, he is making the image fairytale like, suggesting perhaps how unlikely it would be for a woman to be faithful. • Donne also uses the paradoxical idea of things "invisible to see" which further emphasises this idea. • Again the suggestion of time implicit in the line is surely a reference to other love poets and their impossible promises to women, to love them forever and a day etc etc. Stanza 2 Analysis cont. • In this part of the poem it seems as if he is challenging the reader to find evidence contrary to his opinion, asserting that it simply does not exist: "Thou, when thou return'st, wilt tell me...[that nowhere]...Lives a woman true, and fair". • What is odd is that here Donne seems to be saying that it is only beautiful women who will be unfaithful, does this mean that the ugly women will be? • The repeated "thou" is accusing, it seems as though the listener is in fact such a woman, beautiful and inconstant. • The tone at the end of this stanza is far more personal, and the syntax more difficult; this is perhaps an indication of personal feeling, of his mistrust. Stanza 2 • If thou beest born to strange sights, Things invisible to see, Ride ten thousand days and nights, Till age snow white hairs on thee, Thou, when thou return'st, wilt tell me All strange wonders that befell thee, And swear • 如果你生来有异禀,看得见 No where 人家不能看见的花样, Lives a woman true, and fair. 你就骑马一万夜一万天, 直跑到满头顶盖雪披霜, 你回来会滔滔不绝的讲述 你所遭遇的奇怪事物, 到最后 却赌咒 说美人而忠心,世界上可没有。 Stanza 3 • If thou find'st one,let me know, Such a pilgrimage were sweet; Yet do not, I would not go, Though at next door we might meet; Though she were true when you met her, and last till you write your letter, Yet she • 你万一找到了,通知我一句 Will be False, ere i come, to two, or three. 向这位千里进香也心甘; 可是算了吧,我决不会去, 哪怕到隔壁就可以见面; 尽管你见她当时还可靠, 到你写信了还可以担保, 她不等 我到门 准已经对不起两三个男人。 Stanza 3 Analysis • The final stanza begins in a sardonic manner, "if thou findst one, let me know", he appears to be expressing the opinion that a woman of character and beauty is implausible. • It is comparatively colloquial, there being no images to speak of and the words are less poetic, and less apparently organised than in the previous two stanzas. • It seems dismissive of women, it all seems to be a waste of time, he is saying that even if you do find the woman I'm looking for, it will take only the time of you writing a letter for her to be unfaithful to "two, or three" other men. • The monosyllabic style of these lines accentuates the sense of boredom and irritation, as does the naïve rhyme used for the final triplet. Form and Structure • However this naïve rhyme does add to the phonological quality of the poem, as the simplicity is perhaps more songlike than the rest of the poem. • The regular rhyme and meter of the poem also help to create this feeling. • There is a very tight verse structure, which consists of a sestet of ABAB rhyme preceding the rhyming triplet in each stanza. • The triplet shows an insistence of opinion, it emphasises the points being made but also creates a lilting rhythm to the end of each verse, like the refrain to a song. • The two very short lines immediately precede a far longer one, thus creating contrast, which mirrors the contrasting images in the poem. Form and Structure cont. • E.g., there is the heavenly image of a "falling star" adjacent to the earth bound image of the "mandrake root", then there follows the lovely image of the "mermaids singing" with the ugly apparition of the devil. It would seem that light and dark are being paralleled, and it is strange imagery to use when describing love and constancy. • This is continued into the 2nd stanza where in the 3rd line there is the contrast between day and night, which continues to express images of lightness and darkness as in the 1st stanza. • Significant also is the idea of a "pilgrimage", this seems to tie in with the other religious elements in the poem and suggests sacrifice and religious Puritanism, but this serious image is immediately followed by a light hearted quip, "Yet do not, I would not go, / Though at next door we might meet..." . This seems to mock the seriousness of love in other poems, he seems cynical about women, but not in a way which could be construed as misogynistic. Form and Structure cont. • It seems that the poem is rebuking one lady in particular as it appears to be directed specifically, and yet it is rhetoric; no answer seems to be expected. • It could be said therefore that this poem is predominantly light and mocking in tone, but with an undercurrent of cynicism. • This is reflected in the contrasting pairs of images such as light and dark, and of the ugly and the beautiful; and it seems that in the main, those images also relate in some way to religion. • It is typical of Donne to use such mixed images and to relate love to religion, and this is evident in the poem. Prejudice against Females • 我得知有等妇人,比死还苦;她的心是罗网,手 是锁链,凡蒙神喜悦的人,必能躲避她;有罪的 人,却被她缠住了。传道者说:“看哪,一千男 子中,我找到一个正直人;但众女子中,没有找 到一个。”我将这些事一一比较,要寻求其理, 我心仍要寻找,却未曾找到。我所找到的,只有 一件,就是神造人原是正直,但他们寻出许多巧 计。 Thaks!