Common Core Standards and Physical Education

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO 1

COMMON CORE

STANDARDS AND

PHYSICAL BEST

Jan G. Bishop, Ph.D.

Central CT State University

Debra A. Ballinger, Ph.D.

East Stroudsburg University of PA

Abstract – Program Overview

2

Physical Best has been hailed as a supplement to

K-12 physical education and is now a key component of the Presidential Youth Fitness

Program.

Physical Best supports National Standards in physical education, health, and dance.

Enter a new challenge—the Common Core State

Standards.

Learn how Physical Best supports the CC with well prepared moves and a few new tricks.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Learning Objective/Outcome:

3

…participants will be able to:

select and teach Physical Best activities that clearly support the Common Core State

Standards. use/create lesson extensions to support the Common

Core State Standards identify reasons that quality physical education programs should support the Common Core State

Standards

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Mission/Purpose

4

The Common Core State Standards provide a consistent, clear understanding of what students are expected to learn , so teachers and parents know what they need to do to help them.

The standards are designed to be robust and relevant to the real world , reflecting the knowledge and skills that our young people need for success in college and careers.

With American students fully prepared for the future, our communities will be best positioned to compete successfully in the global economy .

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Common Core Standards - 2012

5

The Common Core standards were introduced to schools throughout the nation in 2010 and have been adopted by 45 states.

Designed as a robust, nationwide set of school standards, the

Common Core program builds off the state standards already in place.

The standards prepare students for college and the workforce by providing them with various skills that enforce writing, thinking critically, and solving real-world problems.

The program focuses primarily on Math and English language arts , which extend to all school subjects, including physical education.

(Spark: http://www.sparkpe.org/blog/how-common-core-can-beimplemented-in-p-e/)

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Why a Common Core?

6

21st century learning is at the heart of the Common

Core.

The 21st century skills are going to support our students to be ready for college, career and beyond and to be successful in whatever the new careers are going to look like in the years to come.

That 21st century learning brings the relevance into the classroom because it’s really about today.

It’s about their experience - whether it was technology or media - and about the careers that they might dream about engaging in as they go on beyond our classroom experience. (Leith, 2012)

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

7

Acknowledging the Controversy

Initial widespread acceptance

Recent push-back

Time to convert curriculum

Teacher evaluations

Testing

Impact on Physical Education

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

8

Why Common Core & PE?

Education of the whole child is our first responsibility.

We can communicate the highest expectations for every student by sharing the standards:

by posting the standards documents around the room,

giving students digital access to the standards,

making sure that students recognize these standards are for them,

(Leith, 2012)

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

9

Teaching CC within our Discipline

Interdisciplinary teaching

Teaching within physical education

PE Literacy

Fitness terms

Strategies

PE Math

HR Formulas

PE Science

Body Composition

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

10

Mathematics

The Standards for Mathematical Practice describe varieties of expertise that mathematics educators at all levels should seek to develop in their students. These practices rest on important

“processes and proficiencies” with longstanding importance in mathematics education.

The first of these are the NCTM process standards of

problem solving,

reasoning and proof,

communication,

representation, and

connections.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Mathematics

11

The second are the strands of mathematical proficiency specified in the

National Research Council’s report Adding It Up :

adaptive reasoning,

strategic competence,

conceptual understanding (comprehension of mathematical concepts, operations and relations),

procedural fluency (skill in carrying out procedures flexibly, accurately, efficiently and appropriately), and

productive disposition (habitual inclination to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile, coupled with a belief in diligence and one’s own efficacy).

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Mathematics

12

In essence, Math comprises a range of skills far beyond solving equations.

Here are some suggestions from SPARK related to P.E. and the Common Core…

Graphs: Students should create graphs and charts that show their results for a given activity. For example, when students run timed laps, you can have them chart out their times and see their progress over the course of a month.

Skip counting: Normally, when your students warm up or do stretches, they count by ones. Switch things up by having kids skip count progressively. For example, they can do ten jumping jacks counting by ones (1, 2, 3, 4…), then do toe touches for ten seconds but counting by twos (2, 4, 6, 8…). This is a great way to combine physical activity with multiples.

Pedometers: Pedometers can be used for all kinds of fun math-related activities.

Kids can wear pedometers during class to see how many steps they’ve taken and then challenge themselves to take more steps during the next class. They can add the numbers together to see how many total steps they took.

http://www.sparkpe.org/blog/how-common-core-can-be-implemented-in-p-e/

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

13

Math Common Core and

Physical BEST Elementary

Now that you have a different perspective, let’s try some Math Standard-related Physical Best Activities:

Elementary Level:

PB 3.15 Aerobic Scooters (primary) (p. 66) Reading Children’s

OMNI chart [problem solving, reasoning & truth; representations and connections]

P.B. 3.2 Frantic Ball (intermediate) (p. 34) Taking HR, Using a Star passing pattern, comparing resting HR to activity HR.

[ Quantitative reasoning entails habits of creating a coherent representation of the problem at hand; considering the units involved; attending to the meaning of quantities, not just how to compute them]

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

14

Math Common Core and

Physical BEST Secondary

PB Sec. 3.8 Continuous Relay

Ratio/proportional concepts, applied math

PB Sec 3.10 1,000 Reps

Ratio/proportional concepts, applied math

PE Sec 8.3 Using Pedometers to Set Goals and

Assess Physical Activity

Define quantities for descriptive modeling

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Reading

15

Again, from the SPARK website…

A focus in the Common Core standards is developing verbal and reading skills .

… providing verbal cues and instructions each day is a good starting point… push it further with:

Station cards: During an activity that involves moving between several different stations, create station cards that offer in-depth written instructions for what to do next for critical thinking/comprehension practice .

Read-alouds: Also known as shared reading , read-alouds give students a chance to hear fluent reading. Provide hand-outs and read out loud while your students follow along . They can then keep the hand-outs to peruse later or to reinforce your verbal instructions.

Bulletin boards: Provide a bulletin board that gives your students instructions, tasks that must be accomplished, or provides a lesson that they must apply during class.

Create a PE word wall that displays important vocabulary—movement words, health terms, names of muscle groups

—that will be used throughout the day’s lesson.

Supplemental texts: Post or hand out supplemental materials about the sport or skill you’re currently covering. For instance, if you are on your baseball unit, post a short history of baseball, the basic rules, fun facts, and profiles of athletes. http://www.sparkpe.org/blog/how-common-core-can-be-implemented-in-p-e/

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Physical BEST Elementary and Reading:

16

Now, let’s examine some Physical BEST reading related activities:

Elementary Level:

Primary – 6.5 – Brown bag dinner (p. 180)

Reading food words and comparing with pictures

Primary 3.6 – Power Ball Hunt (p. 42)

Reading cards and comparing with numbers

Intermediate – 8.7 – Heart Smart Orienteering (p. 244)

Shared reading and station cards following directions.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Physical BEST Secondary and Reading

17

PB Sec 4.4 Muscle FITT Bingo

Vocabulary, Matching words and actions

PB Sec 4.10 Know Your Way Around the Weight

Room

Information on resistance training, multiple sources

PB Sec 6.2 Body Comp Survivor

Textual evidence, domain-specific words

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Writing

18

Finally, let’s look at writing:

Proficient writing has become one of the most important skills in the modern day. SPARK suggests integrating writing the P.E.

curriculum as follows:

Setting goals : Have students write down their goals before an activity or at the start of the week. At the end of the activity or the week, have kids provide a post-assessment of what they accomplished and what they could have done better.

Health and fitness journals: An extension of the above, you can have each student compile an in-depth journal that records their fitness goals for the entire year and includes a daily breakdown of the foods they ate and the physical activities they performed.

Create a new game: Split kids into groups and have them write out the rules and directions for a new game. They can then provide a quick demonstration of the new game, and you can choose from the best to play during the next class period.

Educational brochures : Kids can create informational brochures on various subjects, like the importance of physical activity, nutrition, or how to maintain a healthy heart. You can then make copies and distribute them or post them on your bulletin board.

Home fitness projects: These projects extend the lessons kids learn in class to their lives at home. Have them write out ideas for living healthy outside of school.

Create a class website or blog: Put kids in charge of certain elements of the blog or website and encourage students to contribute to the blog by writing short posts and comments. This is also a great way to build students’ technological proficiency. http://www.sparkpe.org/blog/how-common-core-can-be-implemented-in-p-e/

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

19

Examples of Writing from

Physical BEST - Elementary

Goal Setting

Elementary - P.B. 3.13 - Musical Sport Sequence (primary) (p.

60)

Combining different activities to meet 60 minutes per day of MVPA.

Homework – writing different types of activities

Journaling

PB 3.17 Aerobic FITT Log (intermediate) (p. 71) Principles of

Progression & Overload [logging FITT; problem solving, reasoning & truth; representations and connections]

Home fitness projects

Intermediate – 8.7 – Heart Smart Orienteering (p. 244)

Shared reading and station cards following directions .

FITT homework sheets

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

20

Examples of Writing from

Physical BEST - Secondary

PB Sec. 9.1 & 9.2 Health and Fitness Quackery

Write an argument

PB Sec. 10.1 Program Planning

Write informative/explanatory text – technical process

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Getting Started with PB & CCSS

21

Step 1 – Select your P.B. Activity to align with PE or

Health Standard – use the table of contents

Step 2 – Identify the grade level of your students

Step 3 - If reproducible is included, think about where it best fits. *Decide which CC Area (Math,

Reading, Writing, etc.) it best reinforces.

Step 4 – Look up/review the CCSS in that area by grade level.

Step 5 – Modify/extend the activity to include

CCSS

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

22

Checking for Understanding…

Why should quality physical education programs support the Common Core State Standards?

Can you give examples of the types of Physical

Best activities useful for supporting the CCSS?

As you leave here, do you feel you can select and teach Physical Best activities that support the

CCSS?

If not, please ask a question :}

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

References

23

Implementing the Common Core State Standards. http://www.corestandards.org/

James-Hassan, M. (2014). Supporting the Common Core in Health and Physical Education.

Principal Leadership. February, 2014.

Leith, L. (2012). “Common Core Standards: Equity and Opportunity” School Improvement

Network. http://www.schoolimprovement.com/docs/Jan-Webinar-Common-Core-

Standards-Equity-and-Opportunity.pdf

[Retrieved 2_19_2014]

NASPE (2011). Physical Best Activity Guide – Elementary Level (3 rd

Kinetics Pub.

Ed.) Champaign, IL: Human

NASPE (2011). Physical Best Activity Guide – Secondary Level (3 rd

Kinetics Pub.

Ed.) Champaign, IL: Human

SPARK (2014). “How Common Core Can Be Implemented in P.E.” http://www.sparkpe.org/blog/how-common-core-can-be-implemented-in-p-e/

[retrieved 2-19_2014]

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Link to Standards

24

http://www.corestandards.org/

http://www.corestandards.org/Math/Practice

http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/R

http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/W

http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/SL

http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/CCRA/L

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

25

Your turn – Small group activity

PB Elem 3.12

Around the Block (Primary & Intermediate) Common Core: _____

Students will describe how time relates to aerobic fitness. They walk around the sidewalk/gym for 2 minutes, then stop and record HR and steps; Next jog around course..record. Next leap over objects/hurdles, and record. During each segment of the lesson, they will take their heart rates and record them, and wear pedometers and chart steps.

Extension: Have primary students complete Around the Block Home Worksheet with the help of parents/guardians, and return it to class. Have intermediate grades children use the Around the Bock

Timed Activity to evaluate activities outside of the school.

Purpose/Essential Question: How much time is needed to give the body an aerobic workout?

Collect data: Have students place a hand on the heart and use the other hand to do opening and closing motions to demonstrate how fast the heart is beating. Count the number of beats for six seconds, and the multiply by ten.

Chart data:

Interpret chart:

Conclusion:

Discussion:

Write down your actual heart rates during class segments.

In a table, write down the number of pedometer steps for each activity, and their number of beats in 6 seconds for each activity.

Decide what happened with your heart rate during each activity segment.

Heart rate increases as exercise intensity increases.

Why do you think heart rate did what it did?

What is a desirable pattern for heart rate? Why?

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Your turn – Small group activity

26

PB Elem 4.5Opposing Force (primary) Common Core: _____

Students will identify activities that use muscular strength daily.

In pairs, one student performs the depicted “sitter” activity, while their partner performs the “runner” activity. They then exchange roles, with the sitter performing the runner activity

#2, while their partner performs the sitter activity #2.

Continue each activity segment for 1-2 minutes.

Extension: Order the activities from easiest to most difficult…by placing a 1 for easiest, on each sheet.

Ask students to write down three more daily living activities/chores, and 3 more physical activities from P.E. class, that use muscular strength and endurance.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

27

PB Elem 5.1 You Can Bend (primary)

Common Core: _____

Children will be able to identify the importance of stretching for physical activity preparation and daily living. The will be able to define flexibility. Using the handouts, children view the pictures, then try the depicted flexibility exercise.

After completing the activities, they circle the ones that were most fun, and put an “X” through those they could not do.

Then, using the You Can Bend Homework Worksheet, they draw 3 pictures of something they did at home that needed flexibility.

Extension – select one activity that they could not do, write it down, and draw a picture. Take it home an practice it 5 times each day for one week.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

28

PB Elem 5.6

Stretch out tag (intermediate)

Common Core: _____

Purpose – to teach about warm up and cool down activities.

Students will be able to list exercises to use for warm-up, for cool down, and for stretching/flexibility.

Extensions –

Have students find 5 new words on the station cards. Write down the new words, and look up in the dictionary the definitions of the words. Bring definitions back to the next class; be prepared to share what they learned with the class.

Have the students create new flexibility or warm-up activities to bring in for the next class. For each exercise, include the name of the exercise, how long to hold it or perform it, and why it is important.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

PE Elem 6.3 Activity Time Common Core: ___

29

Students participate in moderate to vigorous physical activity.

They each have a Clock Illustration handout, and stand on a poly spot which is their home base. Teacher selects a locomotor movement and plays music to start an activity.

When the music stops, the students pick up one bean bag and take it back to their clock/spot. (Use a variety of aerobic and muscular activities.) Continue until they have completed 6 activities. Each bean bag = 10 minutes. Have them place the bean bags on each arm of the clock…adding up to 60 minutes of daily physical activity.

Extension: Stop after 3…or 4 activities. Have them place bean bags on the clock. Figure out how many more minutes are needed to get 60 minutes of physical activity.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

30

PB Elem. 7.8

Black out Fitness Bingo

(intermediate) Common Core: _____

Students evaluate exercises and classify them as primarily developing health-related or skill-related fitness. In a small group, students perform all of the exercises on the BINGO card. They decide whether each activity is health- or skillrelated fitness. When they are finished, they must check their answers against a master chart or with the teacher.

Home extension: Have student design their own Blackout

Fitness Bingo Card of health- and skill-related fitness on a blank card.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

31

PB Goal Setting worksheets (intermediate)

Common Core: _____

Students chart how many times they did a specific activity (such as a jump rope, stretching, or other exercise from Black out

Fitness Bingo or other activities. Have them add 2 repetitions to each activity, to set as a goal for the next week. Have them write them using the “Goal Setting” Worksheet, from Chapter

2.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Additional Reading

32

Jan – the following are the standards and their explanations from CC web site. While I don’t see using these in the presentation, it is good to have them for questions and discussions if anyone has any…so left them here at the end of the presentation slides.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

33

Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them.

Mathematically proficient students start by explaining to themselves the meaning of a problem and looking for entry points to its solution.

They analyze givens, constraints, relationships, and goals .

They make conjectures about the form and meaning of the solution and plan a solution pathway rather than simply jumping into a solution attempt.

They consider analogous problems, and try special cases and simpler forms of the original problem in order to gain insight into its solution.

They monitor and evaluate their progress and change course if necessary.

Older students might, depending on the context of the problem, transform algebraic expressions or change the viewing window on their graphing calculator to get the information they need.

Mathematically proficient students can explain correspondences between equations, verbal descriptions, tables, and graphs or draw diagrams of important features and relationships, graph data, and search for regularity or trends.

Younger students might rely on using concrete objects or pictures to help conceptualize and solve a problem.

Mathematically proficient students check their answers to problems using a different method, and they continually ask themselves, “Does this make sense?”

They can understand the approaches of others to solving complex problems and identify correspondences between different approaches.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

34

Reason abstractly and quantitatively

Mathematically proficient students make sense of quantities and their relationships in problem situations.

They bring two complementary abilities to bear on problems involving quantitative relationships:

the ability to decontextualize —to abstract a given situation and represent it symbolically and manipulate the representing symbols as if they have a life of their own, without necessarily attending to their referents—

and the ability to contextualize , to pause as needed during the manipulation process in order to probe into the referents for the symbols involved.

Quantitative reasoning entails habits of creating a coherent representation of the problem at hand; considering the units involved; attending to the meaning of quantities, not just how to compute them; and

Knowing and flexibly using different properties of operations and objects.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

35

Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.

Mathematically proficient students understand and use stated assumptions, definitions, and previously established results in constructing arguments.

They make conjectures and build a logical progression of statements to explore the truth of their conjectures.

They are able to analyze situations by breaking them into cases, and can recognize and use counterexamples.

They justify their conclusions, communicate them to others, and respond to the arguments of others.

They reason inductively about data, making plausible arguments that take into account the context from which the data arose.

Mathematically proficient students are also able to compare the effectiveness of two plausible arguments, distinguish correct logic or reasoning from that which is flawed, and—if there is a flaw in an argument— explain what it is.

Elementary students can construct arguments using concrete referents such as objects, drawings, diagrams, and actions . Such arguments can make sense and be correct, even though they are not generalized or made formal until later grades.

Later, students learn to determine domains to which an argument applies .

Students at all grades can listen or read the arguments of others , decide whether they make sense, and ask useful questions to clarify or improve the arguments.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Model with mathematics

36

Mathematically proficient students can apply the mathematics they know to solve problems arising in everyday life, society, and the workplace.

In early grades, this might be as simple as writing an addition equation to describe a situation.

In middle grades, a student might apply proportional reasoning to plan a school event or analyze a problem in the community.

By high school, a student might use geometry to solve a design problem or use a function to describe how one quantity of interest depends on another.

Mathematically proficient students who can apply what they know are comfortable making assumptions and approximations to simplify a complicated situation, realizing that these may need revision later.

They are able to identify important quantities in a practical situation and map their relationships using such tools as diagrams, two-way tables, graphs, flowcharts and formulas.

They can analyze those relationships mathematically to draw conclusions.

They routinely interpret their mathematical results in the context of the situation and reflect on whether the results make sense, possibly improving the model if it has not served its purpose.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Use appropriate tools strategically

37

Mathematically proficient students consider the available tools when solving a mathematical problem. These tools might include pencil and paper, concrete models, a ruler, a protractor, a calculator, a spreadsheet, a computer algebra system, a statistical package, or dynamic geometry software.

Proficient students are sufficiently familiar with tools appropriate for their grade or course to make sound decisions about when each of these tools might be helpful, recognizing both the insight to be gained and their limitations.

For example, mathematically proficient high school students analyze graphs of functions and solutions generated using a graphing calculator. They detect possible errors by strategically using estimation and other mathematical knowledge.

When making mathematical models, they know that technology can enable them to visualize the results of varying assumptions , explore consequences, and compare predictions with data.

Mathematically proficient students at various grade levels are able to identify relevant external mathematical resources, such as digital content located on a website, and use them to pose or solve problems.

They are able to use technological tools to explore and deepen their understanding of concepts.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Attend to precision.

38

Mathematically proficient students try to communicate precisely to others.

They try to use clear definitions in discussion with others and in their own reasoning.

They state the meaning of the symbols they choose, including using the equal sign consistently and appropriately.

They are careful about specifying units of measure, and labeling axes to clarify the correspondence with quantities in a problem.

They calculate accurately and efficiently, express numerical answers with a degree of precision appropriate for the problem context.

In the elementary grades, students give carefully formulated explanations to each other.

By the time they reach high school they have learned to examine claims and make explicit use of definitions.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Look for and make use of structure.

39

Mathematically proficient students look closely to discern a pattern or structure.

Young students, for example, might notice that three and seven more is the same amount as seven and three more, or they may sort a collection of shapes according to how many sides the shapes have.

Later, students will see 7 × 8 equals the well remembered 7 × 5 + 7 × 3, in preparation for learning about the distributive property. In the expression x 2

+ 9 x + 14, older students can see the 14 as 2 × 7 and the 9 as 2 + 7.

They recognize the significance of an existing line in a geometric figure and can use the strategy of drawing an auxiliary line for solving problems.

They also can step back for an overview and shift perspective. They can see complicated things, such as some algebraic expressions, as single objects or as being composed of several objects. For example, they can see

5 – 3( x – y ) 2 as 5 minus a positive number times a square and use that to realize that its value cannot be more than 5 for any real numbers x and y .

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

40

Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning.

Mathematically proficient students notice if calculations are repeated, and look both for general methods and for shortcuts

Upper elementary students might notice when dividing 25 by 11 that they are repeating the same calculations over and over again, and conclude they have a repeating decimal. By paying attention to the calculation of slope as they repeatedly check whether points are on the line through (1, 2) with slope 3, middle school students might abstract the equation ( y – 2)/( x – 1)

= 3. Noticing the regularity in the way terms cancel when expanding ( x –

1)( x + 1), ( x

– 1)( x 2 + x + 1), and ( x

– 1)( x 3 + x 2 + x + 1) might lead them to the general formula for the sum of a geometric series.

As they work to solve a problem, mathematically proficient students maintain oversight of the process, while attending to the details.

They continually evaluate the reasonableness of their intermediate results.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

READING Key Ideas and Details

41

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.3

Analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Craft and Structure

42

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4

Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.5

Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

43

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.7

Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

1

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.9

Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Reading/Literature

44

The anchor standard for reading for literature is number nine:

The standard says that students should be able to analyze how two or more texts address similar themes so that they can build knowledge and also so that they can compare the approaches the authors take.

(Leith, 2012)

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

45

Range of Reading and Level of Text

Complexity

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.10

Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

46

Note on range and content of student reading

To build a foundation for college and career readiness, students must read widely and deeply from among a broad range of highquality, increasingly challenging literary and informational texts.

Through extensive reading of stories, dramas, poems, and myths from diverse cultures and different time periods, students gain literary and cultural knowledge as well as familiarity with various text structures and elements. By reading texts in history/social studies, science, and other disciplines, students build a foundation of knowledge in these fields that will also give them the background to be better readers in all content areas. Students can only gain this foundation when the curriculum is intentionally and coherently structured to develop rich content knowledge within and across grades. Students also acquire the habits of reading independently and closely, which are essential to their future success.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

47

College and Career Readiness

Anchor Standards for Writing

The K-12 standards on the following pages define what students should understand and be able to do by the end of each grade. They correspond to the

College and Career Readiness (CCR) anchor standards below by number. The CCR and gradespecific standards are necessary complements—the former providing broad standards, the latter providing additional specificity—that together define the skills and understandings that all students must demonstrate.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Text Types and Purposes

1

48

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.1

Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2

Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.3

Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details and well-structured event sequences.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

49

Production and Distribution of

Writing

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4

Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.5

Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.6

Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

50

Research to Build and Present

Knowledge

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.7

Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.8

Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source, and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.9

Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Range of Writing

51

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.10

Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

52

Note on range and content in student writing

To build a foundation for college and career readiness, students need to learn to use writing as a way of offering and supporting opinions, demonstrating understanding of the subjects they are studying, and conveying real and imagined experiences and events. They learn to appreciate that a key purpose of writing is to communicate clearly to an external, sometimes unfamiliar audience, and they begin to adapt the form and content of their writing to accomplish a particular task and purpose. They develop the capacity to build knowledge on a subject through research projects and to respond analytically to literary and informational sources.

To meet these goals, students must devote significant time and effort to writing, producing numerous pieces over short and extended time frames throughout the year.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

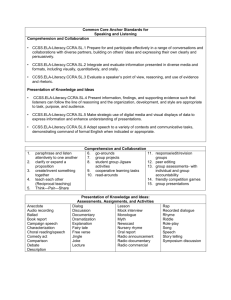

Comprehension and Collaboration

53

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.3

Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

54

Presentation of Knowledge and

Ideas

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.4

Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.5

Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.6

Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and communicative tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

55

Note on range and content of student speaking and listening

To build a foundation for college and career readiness, students must have ample opportunities to take part in a variety of rich, structured conversations—as part of a whole class, in small groups, and with a partner. Being productive members of these conversations requires that students contribute accurate, relevant information; respond to and develop what others have said; make comparisons and contrasts; and analyze and synthesize a multitude of ideas in various domains.

New technologies have broadened and expanded the role that speaking and listening play in acquiring and sharing knowledge and have tightened their link to other forms of communication. Digital texts confront students with the potential for continually updated content and dynamically changing combinations of words, graphics, images, hyperlinks, and embedded video and audio.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

56

College and Career Readiness

Anchor Standards for Speaking and

Listening

The K–12 standards on the following pages define what students should understand and be able to do by the end of each grade. They correspond to the

College and Career Readiness (CCR) anchor standards below by number. The CCR and gradespecific standards are necessary complements—the former providing broad standards, the latter providing additional specificity—that together define the skills and understandings that all students must demonstrate.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

Comprehension and Collaboration

57

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.3

Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

58

Presentation of Knowledge and

Ideas

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.4

Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.5

Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.6

Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and communicative tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

59

Note on range and content of student speaking and listening

To build a foundation for college and career readiness, students must have ample opportunities to take part in a variety of rich, structured conversations—as part of a whole class, in small groups, and with a partner. Being productive members of these conversations requires that students contribute accurate, relevant information; respond to and develop what others have said; make comparisons and contrasts; and analyze and synthesize a multitude of ideas in various domains.

New technologies have broadened and expanded the role that speaking and listening play in acquiring and sharing knowledge and have tightened their link to other forms of communication. Digital texts confront students with the potential for continually updated content and dynamically changing combinations of words, graphics, images, hyperlinks, and embedded video and audio.

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO

60

English Language Arts Standards:

Standard 10: Range, Quality, &

Complexity - Staying on Topic Within a Grade & Across Grades

Building knowledge systematically in English language arts is like giving children various pieces of a puzzle in each grade that, over time, will form one big picture. At a curricular or instructional level, texts—within and across grade levels—need to be selected around topics or themes that systematically develop the knowledge base of students. Within a grade level, there should be an adequate number of titles on a single topic that would allow children to study that topic for a sustained period.

The knowledge children have learned about particular topics in early grade levels should then be expanded and developed in subsequent grade levels to ensure an increasingly deeper understanding of these topics. Children in the upper elementary grades will generally be expected to read these texts independently and reflect on them in writing. However, children in the early grades (particularly K–2) should participate in rich, structured conversations with an adult in response to the written texts that are read aloud, orally comparing and contrasting as well as analyzing and synthesizing, in the manner called for by the

Standards.

Preparation for reading complex informational texts should begin at the very earliest elementary school grades. What follows is one example that uses domain-specific nonfiction titles across grade levels to illustrate how curriculum designers and classroom teachers can infuse the English language arts block with rich, age-appropriate content knowledge and vocabulary in history/social studies, science, and the arts. Having students listen to informational read-alouds in the early grades helps lay the necessary foundation for students’ reading and understanding of increasingly complex texts on their own in subsequent grades.

See: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/standard-10-range-quality-complexity/staying-on-topic-within-a-gradeacross-grades

2014 AAHPERD, St. Louis, MO