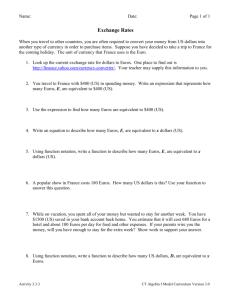

intltrade

advertisement

International Trade Exchange Rates and Open Macroeconomic Models October 17, 2006 International trade is more complicated than domestic trade. There are no national borders to be crossed when, say, California wine is shipped to Delaware. The consumer in Newark pays with Dollars, just the currency that the wine maker in California wants. If that same vintner ships her wine to Europe, however, consumers there will have only Euros with which to pay, rather than the Dollars the wine maker in California wants. Thus, for international trade to take place, there must be some way to convert one currency into another. The exchange rate states the price in terms of one currency at which such conversions are made. There is an exchange rate between every pair of currencies. For example the British Pound in 2002 was the equivalent of about $1.40. The exchange rate between the Pound and the Dollar, then, may be expressed as roughly "$1.40 to the Pound" (meaning that it costs $1.40 to buy a Pound) or about "71 pence to the Dollar" (meaning that it costs 71 British pence to buy a Dollar). (Currently the rate is $1.86 and .57 respectively) A nation’s currency is said to appreciate when the exchange rates change so that a unit of its currency can buy more units of a foreign currency. A nation’s currency is said to depreciate when the exchange rates change so that a unit of its currency can buy fewer units of a foreign currency. For example if the cost of a Pound rises from $1.40 to $2.00, the cost of a U.S. dollar in terms of pounds simultaneously falls from 71 pence to 50 pence. The UK has experienced an appreciation while the U.S. has experienced a depreciation in its currency. When an officially set exchange rate is altered so that a unit of a nation’s currency can buy fewer units of foreign currency, we say that a devaluation of that currency has taken place. When the exchange rate is changed so that the nation’s currency buys more units of a foreign currency, a revaluation has taken place. EXCHANGE RATE DETERMINATION IN A FREE MARKET Assume that the Dollar and the Euro are the only currencies on earth, so the market needs to determine only one exchange rate. Figure 1 depicts the determination of this exchange rate at the point in the figure where demand curve D1 crosses supply curve S1. At this price ($0.90 per euro), the number of Euros demanded is equal to the number of Euros supplied. $/Euro Euro Market Figure 1 S1 D shifts to the right D shifts to the left .90 S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 0 Q of Euros Q1 Why does anyone demand Euros? International trade in goods and services. (In general, demand for Europe’s exports leads to demand for its currency, Euros) 2. International trade in financial instruments such as stocks and bonds. (In general demand for Europe’s financial assets leads to demand for it’s currency, Euros) 1. 3. Purchases of a country’s (Europe’s) physical assets such as factories and machinery overseas by foreigners (e.g. U.S. citizens). (In general, direct foreign investment leads to demand for Europe’s currency, the Euro) Where does the supply of Euros come from? Europeans want to buy U.S. goods (the other side of 1 above) 2. Europeans want to buy U.S. stocks and bonds (the other side of 2 above) 3. Europeans purchase physical assets in the U.S. (the other side of 3 above) (can use the supply and demand graphs we have already created) 1. To illustrate the usefulness of even this simple supply and demand analysis, think about how the exchange rate between the Dollar and the Euro should change if Europeans become attracted by the prospects of large gains on the U.S. stock markets. To purchase U.S. stocks, foreigners will first have to purchase U.S. Dollars, which means selling some of their Euros. In terms of the supply-demand diagram in Figure 2, the increased desire of Europeans to acquire U.S. stocks would shift the supply curve for Euros out from S1 to S2 . Equilibrium would shift from point Q1 to point Q4, and the exchange rate would fall: e.g. from $0.90 per Euro to $0.80 per Euro. Market for Euros $/Euro S1 D shifts to the right D shifts to the left .90 S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 0 Q of Euros Q1 Market for Euros $/Euro S1 D shifts to the right S2 .90 S shifts to the right .80 0 D shifts to the left S shifts to the left D1 Q1 Q4 Q of Euros Thus the increased supply of Euros by European citizens would cause the Euro to depreciate relative to the dollar. This is what happened during the U.S. stock market boom of the late 1990s. Summary: Suppose that Europeans have an interest in investing in the U.S. stock market. (straight forward supply and demand) To purchase stocks, Europeans need to purchase $ => selling Euros. (supply curve for Euros shifts to the right => causing the $ price of the Euro to fall) Interest Rates and Exchange Rates: The Short Run Main determinant in the short run: interest rates, in particular interest rate differentials, and financial flows. As an example, suppose the Italian government bonds pay a 5 percent rate when yields on equally safe U.S. government securities rise to 7 percent. Italian investors will be attracted by the higher interest rates in the United States and will offer Euros for sale. Why? To buy Dollars and use those Dollars to buy U.S. securities. At the same time, U.S. investors will find it more attractive to keep their money at home, so fewer Euros will be demanded by Americans. $/Euro Euro Market Figure 3 S1 D shifts to the right D shifts to the left P1 S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 0 Q of Euros Q1 Figure 3 Euro Market $/Euro S1 D shifts to the right S2 D shifts to the left P1 S shifts to the right P4 S shifts to the left 0 D1 Q1 Q4 Q of Euros Figure 3 Euro Market $/Euro S1 D shifts to the right S2 P1 = 1.20 D shifts to the left S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 P2= 1.10 0 D2 Q1 Q2 Q of Euros When the demand schedule shifts inward and the supply curve shifts outward, the effect on price is predictable. The Euro will depreciate, as Figure 3 shows. In the figure, the supply curve of Euros shifts outward from S1 to S2 when Italian investors seek to sell Euros in order to purchase more U.S. securities. At the same time, American investors wish to buy fewer Euros because they no longer desire to invest as much in Italian securities. Thus, the demand curve shifts inward from D1 to D2. The Result: In our example, there is a depreciation of the Euro from $1.20 to $1.10. Exercise: Suppose that interest rates are higher in Europe than in the U.S. Demonstrate using supply and demand curves that this would cause the Euro to appreciate. In general Other things equal, countries that offer investors higher rates of return attract more capital than countries that offer lower rates. Thus, a rise in interest rates often will lead to an appreciation of the currency, and a drop in interest rates will lead to a depreciation of the currency. Interest rate differentials certainly played a predominant role in the stunning movements of the U.S. Dollar in the 1980s. In the early 1980s, American interest rates rose well above comparable interest rates abroad. As a result, foreign capital was attracted to the U.S. American capital stayed at home, and the Dollar soared. That is, the Dollar appreciated. Similarly, a nation that suffers from capital flight, as did Argentina in 2001, must offer extremely high interest rates to attract foreign capital. Interest Rates and Exchange Rates: The Medium Run The medium run is where the theory of exchange rate determination is most unsettled. Economists once reasoned as follows: Because consumer spending increases when income rises and decreases when income falls, the same thing is likely to happen to spending on imported goods. So a country's imports will rise quickly when its economy booms and rise only slowly when its economy stagnates. For the reasons illustrated in Figure 4, a boom in the United States should shift the demand curve for Euros outward as Americans seek to acquire more Euros to buy more European goods and services. And that, in turn, should lead to an appreciation of the Euro (depreciation of the Dollar). In the figure, the Euro rises in value from P1 to P2 Dollars per Euro. Figure 4 Euro Market $/Euro S1 D shifts to the right D shifts to the left P1 S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 0 Quantity of Euros Q1 Figure 4 Euro Market $/Euro S1 D shifts to the right P2 D shifts to the left P1 D2 S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 0 Quantity of Euros Q1 Q2 However, if Europe was booming at the same time, Europeans would be buying more American exports, which would shift the supply curve of Euros outward. Europeans must offer more Euros for sale to get the Dollars they need for purchasing U.S. goods and services. Figure 4 Euro Market $/Euro S1 S2 D shifts to the right D shifts to the left P3 P1 D2 S shifts to the right S shifts to the left D1 0 Q1 Q3 Quantity of Euros On balance, the value of the Dollar might rise or fall. It appears that what matters is whether exports are growing faster than imports. A country whose aggregate demand grows faster than the rest of the world's normally finds its imports growing faster than its exports. Thus, its demand curve for foreign currency shifts outward more rapidly than its supply curve. Other things equal, that will make its currency depreciate. In the context of figure 4 if the U.S. is growing faster than Europe, D1 will shift out by a larger amount than S1, leading to an appreciation of the Euro. Conclusion: This reasoning is sound - so far as it goes. And it leads to the conclusion that a "strong economy" might produce a "weak currency." But the three most important words in the preceding statement are "other things equal." Usually, they are not. Specifically, a booming economy will normally offer more attractive prospects to investors than a stagnating one -- higher interest rates, rising stock market values, and so on. This difference in prospective investment returns, as we have seen, should attract capital and boost its currency value. So there appears to be a kind of "tug of war." As we see, thinking only about trade in goods and services leads to the conclusion that faster growth should weaken the currency. But thinking about trade in financial assets (such as stocks and bonds) leads to precisely the opposite conclusion: Faster growth should strengthen the currency. Which side will win this "tug of war"? In the modern world, the evidence seems to say that trade in financial assets is the dominant factor. Rapid growth in the United States in the second half of the 1990s led to a sharply appreciating Dollar even though U.S. imports soared. Why? Investors from all over the world brought funds to America. We conclude that: Stronger economic performance appears to lead to currency appreciation because it improves prospects for investing in the country. Purchasing Power Parity Theory: The Long Run In the long run, an apparently simple principle ought to govern exchange rates. As long as goods can move freely across national borders, exchange rates should eventually adjust so that the same product costs the same amount of money, whether measured in Dollars in the United States, Euros in Germany, or Yen in Japan -- except for differences in transportation costs and the like. This simple statement forms the basis of the major theory of exchange rate determination in the long run: The purchasing-power parity theory of exchange rate determination holds that the exchange rate between any two national currencies adjusts to reflect differences in the price levels in the two countries. Example: Suppose German and American steel is identical and that these two nations are the only producers of steel for the world market. Suppose further that steel is the only tradeable good that either country produces. Question: If American steel costs $180 per ton and German steel costs 200 Euros per ton, what must be the exchange rate between the dollar and the euro? Answer: Because 200 Euros and $180 each buy a ton of steel, the two sums money must be of equal value. Hence, each Euro must be worth $0.90. The Dollar price of the Euro is $.90 Why? Any higher price for a Euro, such as $1, would mean that steel would cost $200 per ton (200 Euros at $1 each) in Germany but only $180 per ton in the United States. In that case, all foreign customers would buy their steel in the United States -- which would increase the demand for Dollars and decrease the demand for Euros. In our diagram for the market for Euros the supply of Euros would shift to the right and the result would be a lower Dollar price of the Euro. Similarly, any exchange rate below $0.90 per Euro would send all the steel business to Germany, driving the value of the Euro up toward its purchasingpower parity level. Exercise: Show why an exchange rate of $0.80 per Euro is too low to lead to an equilibrium in the international steel market. Exercise (continued) Dollar price of Euro: $.80 $/Euro =.80 At this exchange rate the: cost of steel in Germany is $160 cost of steel in the U.S. is $180 The purchasing-power parity theory is used to make long-run predictions about the effects of inflation on exchange rates. To continue our example, suppose that steel (and other) prices in the United States rise while prices in Europe remain constant. The purchasing-power parity theory predicts that the Euro will appreciate relative to the Dollar. It also predicts the amount of the appreciation. After the U.S. inflation, suppose that the price of American steel is $220 per ton, while German steel still costs 200 Euros per ton. For these two prices to be equivalent, 200 Euros must be worth $220, or one Euro must be worth $1.10. The Euro, therefore, must have risen from $0.90 to $1.10. According to the purchasing-power parity theory differences in domestic inflation rates are a major cause of exchange rate movements. If one country has higher inflation than another, its exchange rate should be depreciating. For many years, this theory seemed to work tolerably well. Although precise numerical predictions based on purchasing-power parity calculations were never very accurate (see "Purchasing Power Parity and the Big Mac"), nations with higher inflation did at least experience depreciating currencies. But in the 1980s and 1990s, even this rule broke down. For example, although the U.S. inflation rate was consistently higher than both Germany's and Japan's, the Dollar nonetheless rose sharply relative to both the German Mark and the Japanese Yen from 1980 to 1985. The same thing happened again between 1995 and 2000. Clearly, the theory is missing something. What? Many things. But perhaps the principal failing of the purchasing-power parity theory is, once again, that it focuses too much on trade in goods and services. Financial assets such as stocks and bonds are also traded actively across national borders -- and in vastly greater dollar volumes than goods and services. In fact, the astounding daily volume of foreign exchange transactions, more than $1.5 trillion, exceeds an entire month’s worth of world trade in goods and services. The vast majority of these transactions are financial. If investors decide that, say, U.S. assets are a better bet than Japanese assets, the Dollar will rise, even if our inflation rate is well above Japan's. For this and other reasons: Most economists believe that other factors are much more important than relative price levels for exchange rate determination in the short run. But in the long run, purchasing-power parity plays an important role. Market Determination of Exchange Rates: Summary You may have noticed a theme here. International trade in financial assets: certainly dominates short-run exchange rate changes, may dominate medium-run changes, and also influences long-run changes. We can summarize this discussion of exchange rate determination in free markets as follows: 1. We expect to find appreciating currencies in countries that offer investors higher rates of return because these countries will attract capital from all over the world. 2. To some extent, these are the countries that are growing faster than average because strong growth tends to produce attractive investment prospects. However, such fast-growing countries will also be importing relatively more than other countries, which tends to pull their currencies down. 3. Currency values generally will appreciate in countries with lower inflation rates than the rest of the world's, because buyers in foreign countries will demand their goods and thus drive up their currencies. Reversing each of these arguments, we expect to find depreciating currencies in countries with relatively high inflation rates, low interest rates, and poor growth prospects. Some exchange rates today are truly floating, determined by the forces of supply and demand without government interference. Many others are not. Some people claim that exchange rate fluctuations are so troublesome that the world would be better off with fixed exchange rates. For these reasons, we turn next to a system of fixed exchange rates, or rates that are set by governments. Naturally, under such a system the exchange rate, being fixed, is not closely watched. Instead, international financial specialists focus on a country’s balance of payments to gauge movements in the supply of and demand for a currency. I. Defining the Balance of Payments in Practice The preceding discussion makes it look simple to measure a nation's balance of payments position: count up the private demand for and supply of its currency and subtract quantity supplied from quantity demanded. Go to discussion of AD Conceptually, that is all there is to it. But in practice the difficulties are great because we never directly observe the number of dollars demanded and supplied. Actual market transactions show that the number of, say, U.S. Dollars purchased always equals the number of U.S. dollars sold. Unless someone has made a bookkeeping error, this must be so. How, then, can we recognize a balance of payments surplus or deficit? Easy, you say. Just look at the transactions of the central bank, whose purchases or sales must make up the difference between private demand and private supply. If the Federal Reserve is buying dollars, its purchases measure our balance of payments deficit. If the Fed is selling, its sales represent our balance of payments surplus. Thus, the idea is to measure the balance of payments by excluding official transactions among governments. That is, more or less, what is done. In practice, the balance of payments accounts come in two main parts. The current account balance account totals up exports and imports of goods and services, cross-border payments of interest and dividends, and cross-border gifts. The United States has been running large current account deficits for years. But that represents only one part of our balance of payments, for it leaves out all purchases and sales of assets. Purchases of U.S. assets by foreigners bring foreign currency to the United States, and purchases of foreign assets cost us foreign currency. Netting the capital flows in each direction gives us our surplus or deficit on capital the account. In recent years, this part of our balance of payments accounts has registered large surpluses as foreigners have acquired U.S. assets. In what sense, then does the overall balance of payments balance? There are two possibilities. If the exchange rate is floating, all private transactions, that is, current account plus capital account, must add up to zero (dollars purchased = dollars sold). But if, instead, the exchange rate is fixed, as shown in the Figures below, the two accounts need not balance one another. Government purchases or sales of foreign currency make up the surplus or deficit in the overall balance of payments. Equilibrium is where Qd = Qs S Price of Euros 1.00 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 0.30 0.20 D 0.10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Billions of Euros/Year 10 Price of Euros 1.00 Balance of payments deficit Equilibrium is where QS = QD S 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 0.30 0.20 D 0.10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Billions of Euros per year 10 Equilibrium is where Qs = Qd S Price of Euros 1.00 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 0.30 .33 Balance of payments surplus 0.20 0.10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 D 7 8 9 Billions of Euros 10 per year This simple analysis helps us understand why the U.S. trade deficit grew so enormously in the late 1990s. The international value of the Dollar began to climb in 1995. According to the reasoning we have just completed, within a few years such an appreciation of the Dollar should have boosted U.S. imports and damaged U.S. exports. That is precisely what happened. In constant Dollars, American imports soared by 40 percent between 1997 and 2000, while American exports rose just 15 percent. The result was that a $113 billion net export deficit in 1997 turned into a monumental $399 billion deficit by 2000.