Leanna Yeager - Hakuna Matata

advertisement

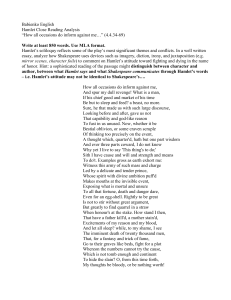

Yeager 1 Leanna Yeager Dr. Johnson Shakespeare December 4, 2013 “Hakuna Matata”: Shakespeare Should Be “No Worries” for the Younger Generation William Shakespeare is a timeless writer who is known for his elegant, poetic language written in perfect iambic pentameter and his use of universal themes. There are many individuals who enjoy Shakespeare’s classical writing, but there is a great amount of people who do not necessarily enjoy his works; this group of people would be the younger generation or also known as high school students (Cunningham). Secondary education scholars and policy makers currently engage in a debate on whether some writers should be taught in school curriculums in the United States. William Shakespeare is one of these writers. Those opposed to having Shakespeare in school curriculums argue that Shakespeare’s language is difficult to understand and students cannot make connections of Shakespeare’s plays to reflect on for their own lives. Those who agree to have Shakespeare in their curriculums, like Karen Cunningham, believe that his works “enrich” our language and his themes are universal to everyday life. It is necessary for educators to identify strategic methods to make this material easier to grasp and understand. Through the course of time, film, media, and stage producers have adapted Shakespearean plays, and some of these adaptations have been created by the Walt Disney Company. The Lion King serves as an excellent adaptation to Hamlet to attract the younger generation. The Broadway production and Julie Taymor’s work on the piece is another tool to attract young people and spark interest in Shakespeare and the theater. I Yeager 2 have discovered proof of how these two adaptations help make understanding Hamlet easier in a secondary English classroom. English teachers understand how difficult and rigorous it is for students to study the works of William Shakespeare. Jim Cope, an English teacher who wrote about the effect of reading tells of his past experience with students with “their reactions beginning and ending with moans.” In his article, he discusses the complaints of one of his students when they were discussing Shakespeare in the classroom: I most definitely hate reading Shakespeare’s plays. Poetry is very hard for me to understand. Shakespeare’s plays are even harder for me to comprehend. The words seem to be backwards or out of order. I hate the language. (Cope) This is a common complaint among many students who are told that they must read a play for class. These students think that Shakespeare is impossible to translate into today’s modern English. Cope gives advice to educators that students should not be reading Shakespeare’s plays like a typical novel. He believes that the best way to teach students Shakespeare’s lines are to give the students a visual and watch the difficult language be played out: “Plays are meant to be heard and seen. They are not to sit on the page and be dissected” (Cope). Adaptations in media are prime examples of these visuals. Lois Burdett, another profound English teacher also states that “using adaptations to help introduce literary elements of a complex text can help students drastically in the study of Shakespeare” (Shaw). The Walt Disney Company depended on William Shakespeare’s plot for helping The Lion King reach as much success it has gained. The Lion King is a loose adaptation of Hamlet by containing the skeleton of the plot. The two plots can be comparable in various literary elements, such as the strands of the plot, characters, and themes (Fenlon). Certain lines of the two Yeager 3 productions can also be compared with Shakespeare’s English language with our modern English language. The plots of Hamlet and The Lion King are similar in a variety of ways. The general plot of Hamlet begins when young Prince Hamlet is approached by the ghost of his late father, King Hamlet of Denmark. King Hamlet tells that he has been poisoned by his brother, Claudius. King Hamlet asks young Hamlet to seek revenge for his father. Throughout the play, Hamlet contemplates how he is going to kill his uncle. Hamlet is eventually exiled from Denmark to England after murdering a minor character, Polonius, after mistaking him for Claudius. Claudius sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to have Hamlet murdered, so he cannot try and come back for the throne. Hamlet then returns with a moving theatre company to try to pull out Claudius’ guilt of his crime. As the play concludes, Claudius, Hamlet, and many other characters fight to the death. Claudius dies at the end of the play, but unfortunately, so does Hamlet by a poisoned sword blade. The plot of The Lion King follows in a similar way. In the opening scenes of The Lion King, viewers see an infant Simba being presented on the top of Pride Rock. The first half of the film shows the father-son bond Mufasa and Simba build as Simba grows up. Unfortunately, Mufasa is killed by Scar during a wildebeest stampede while trying to save young Simba; Scar throws Mufasa down the side of a gorge. After Simba views his father’s dead body, Scar tells Simba that it is his fault and should leave the Pride Lands. Scar then sends his hyena henchmen to kill him. Simba escapes and is found in a desert by a meerkat, Timon, and a warthog, Pumba, who raise him through adolescence. One night, Simba is summoned by a vision of his father in the stars, and tells that he must return to Pride Rock to become king. After much convincing from his friend, Nala, Simba decides to return to fight Scar for his kingdom. Simba reaches Pride Rock and defeats Scar. Pride Rock is now ruled Yeager 4 by the appropriate and rightful king. Although the plots may seem similar to a young generation, there are a couple main differences that teachers must show their students. The first main difference is the opening scenes of the play. Hamlet is greeted by his ghostly father and the scene is set “in media res,” meaning that the play starts in the middle of an action and the viewer/reader does not have any previous information. Viewers never see the father-son bond between Hamlet and King Hamlet like they see Mufasa and Simba’s in The Lion King. Viewers see this bonding with Mufasa and Simba when Mufasa tells him that he will not be alive forever and the kingdom will become his; “A king's time as ruler rises and falls like the sun. One day Simba, the sun will set on my time here- and will rise with you as the new king” (Pollard). The second main difference between the two productions is the ending. Hamlet is a well-known and famous Shakespearean tragedy in which most of the characters, including the protagonist, die a horrific death. This is not the case of The Lion King. The aspect of tragedy is taken out of The Lion King to make it appropriate for the younger audience (Fenlon). Everyone in Pride Rock lives “happily-ever after.” The plot is just one way the two productions can be compared; the characters hold many similarities as well. Disney analyst, Wesley Fenlon, describes the comparisons between the characters in Hamlet and in The Lion King. It is very easy for a high school teacher to have students make character analyses and comparisons of the main characters in the two productions. Simba of course is the character that represents Prince Hamlet, who endures a journey/conflict to rightfully take back his throne from his evil uncle. Dark-maned and green-eyed Scar plays the villain in the film and represents Hamlet’s murderous and power-hungry uncle Claudius. Mufasa, Simba’s father, serves as the representation of King Hamlet. The dynamic duo of Timon and Pumba are comparable to the comic relief characters of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who work under Yeager 5 Claudius while Hamlet is in exile from Denmark. Although Timon and Pumba are friends of Simba in The Lion King, Fenlon states that “Hakuna Matata” pair “indirectly accomplishes the same goal by keeping Simba away from the Pride Lands and his position of leadership.” Characterization is important in two plots, but the themes are where students struggle. Rosemarie Gavin is an educator that believes that “linking a Shakespearean play to a popular children’s movie helps students read and understand.” The central themes of the story are also considered when teaching Hamlet in a high school English classroom. Students have trouble reflecting these themes into their everyday life. One such theme is the archetype of the exiled child. The exiled child has the role to restore the order in the world. They are the ones who have a heroic task. Simba and Hamlet prove this archetype based on the demands of their ghostly fathers. Both of these protagonists each go through a journey to get their throne. Students can gain better understanding of this theme by realizing that they can become heroes in their own lifetime. It may not be to restore peace in a kingdom, but they should know that they can make a difference (Gavin). The other major themes are revenge and responsibility. Simba and Hamlet gain their revenge obviously by killing their chaos-making uncles. The theme of responsibility is observed when the protagonists try to find their way back to the kingdom from exile. They feel the responsibility to return to their homelands because of the respect for their fathers (Gavin). This is seen in a discussion between Hamlet and his two friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: I have of late,—but wherefore I know not,—lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises; and indeed, it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire,—why, it Yeager 6 appears no other thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is man! How noble in reason! how infinite in faculties! in form and moving, how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension, how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals! And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? (Shakespeare 2.2, 287-298) Hamlet is mourning the loss of his father and sees him as an admirable man. A son who sees his father in this light is a son that would do anything for his father, even after death. He feels the responsibility to listen to his father through admiration. This feeling of admiration for his father is seen in The Lion King when Simba talks to Timon and Pumba about his thoughts of the stars above; “somebody once told me that the great kings of the past are up there; watching over us” (Pollod). Simba is referring to Mufasa, who told him this phrase in the beginning scenes of the film; this sparks Simba’s sense of responsibility when he has the realization that he has to return to the Pride Land. The themes of these two productions are seen as universal to many teachers. Managing the themes and their relation to students are one of the main worries for studying Shakespeare in a high school English class. The next problem is language. Teachers can break down Shakespeare’s language by taking passages and comparing them to lines in The Lion King. For example, comparisons of lines can be drawn in the two ghost scenes. “Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder, “(Shakespeare 1.5, 6) is what King Hamlet requests of his living son. Claudius is not fit to rule Denmark. Simba experiences the same when he sees the vision of Mufasa in the stars. Simba does not feel adequate to go back and get the throne, but Mufasa tells him otherwise; “You have forgotten who you are, and so have forgotten me. Look inside yourself, Simba. You are more than what you have become. You must take your place in the Circle of Life” (Pollard). Revenge must be made for Simba to take back Yeager 7 his “place.” Before the fathers disappear to their afterlives, they tell their sons to remember them. King Hamlet says, “Adieu, adieu, adieu. Remember me,” (Shakespeare 1.5, 91), while Mufasa leaves Simba with a simple “Remember” (Pollard). The movie adaptation of The Lion King is one of the great ways to compare the literary elements and understanding of Hamlet; however, there is another way to teach the young generation. William Shakespeare wrote his plays for them to be performed on stage. He was also well-known for his controversial plays and brilliant stage ideas. Education critic, David Roberts explains that students need to be interactive with Shakespeare’s plays to better understand them, which means acting out the lines themselves. Students who participate in this role play “live through the story, discovering it as they go, and contributing from their own perception of character and relationships” (Roberts 352). This allows close readings of texts that can create activities in the classroom. An example of this type of activity would be for a teacher to act as a “director” and try to take out key passages out of the play. The student would take a role as one of the characters and defend why those lines should not be taken out. This type of activity lets the student test their textual analysis, comprehension, and creativity (Roberts). It is also crucial that students understand the nature of the theater and its openness to creativity, and that is exactly what director, Julie Taymor does. Julie Taymor is one of the most popular directors to hit the Broadway stage and film. In her career, she has done many adaptations of Shakespearean plays. One of her adaptations includes the Broadway production of The Lion King. Much like Shakespeare, Taymor has methods out of the ordinary; “I told them I wanted to go for elegance, not cute. The Lion King is a very commercial work, but what they’ve let me do is very experimental” (Zoglin). Taymor’s experiments include a bright and colorful stage, and the performers acting with puppets instead Yeager 8 of being in the costume of the actual animal. Although Taymor went for elegance for this production, she finds many learning opportunities from The Lion King; “I like the message of The Lion King” (Anderson 70). Taymor enjoys the message and themes that the show presents to young children. She believes they are themes that children can reflect on for the rest of their lives. Taymor also find The Lion King to be a stepping stone for those who are interested and want to learn more about the theatre and bond with their families: You know what I love about The Lion King'? It's really theatre operating in its original sense, which is about family and society. It's doing exactly what theatre was born for—to reaffirm where we are as human beings in our environment. It's precisely to reestablish your connection with your family, to know what your hierarchy is. And to watch families come and go through that with their children is a very moving experience for me. (Anderson 75) Although Taymor has left the Broadway production for a few years now, she sees the benefits it gives young children. She gives children the opportunity to enjoy the theatre and gain a better understanding of Shakespeare’s basic plot (Berstein). The methods of teaching Shakespeare have been a constant debate over the past century because of his complexity. It is proven that Shakespeare’s Hamlet can follow the “Hakuna Matata” philosophy and be taught with “no worries” through various adaptations of The Lion King. Teachers can teach the content through various comparisons of literary elements, as well as the differences. With these adaptations, it is easier for educators to decide that Shakespeare should stay in the high school curriculums. Yeager 9 Works Cited Anderson, Thomas P. “Titus, Broadway, and Disney’s Magic Capitalism; Or, The Wonderful World of Julie Taymore.” College Literature 40.1 (2013): 66-95. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 Sept. 2013. Bernstein, Jacob. "Julie Taymor Roars." Newsweek 159.22 (2012): 52-55. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 Sept. 2013. Cope, Jim. "Beyond Voices Of Readers: Students On School's Effects On Reading." English Journal 86.3 (1997): 18. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 Sept. 2013. Cunningham , Karen. “Shakespeare, the Public, and Public Education.” Shakespeare Quarterly 49.3 (1998): 293-298. JSTOR. Web. 24 Sept. 2013. Fenlon, Wesley. “The Lion King: Shakespearean Tragedy Reinvented at Disney's Peak.” Screened. 28 Oct. 2011.Web. 3 Sept. 2013. Gavin, Rosemarie. "The Lion King And Hamlet: A Homecoming For The Exiled Child." English Journal 85.3 (1996): 55.Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 Sept. 2013. Roberts, David. “Shakespeare, Theater Criticism, and the Acting Tradition.” Shakespeare Quarterly 53.3 (2002): 341-361. JSTOR. Web. 24 Sept. 2013. Pollard, Phil. “The Lion King-Script.” Walt Disney Company. New York: Walt Disney Company, 1993. Print. Shakespeare, William. “Hamlet.” The Norton Shakespeare: Essential Plays – The Sonnets. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009. 1080-1168. Print. Shaw, Donna. "Much Ado About William." Curriculum Administrator 35.5 (1999): 46. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 Sept. 2013. Yeager 10 Zoglin, Richard. "The Lion King A Different Breed Of `Cats.'." Time 150.4 (1997): 64. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 Sept. 2013