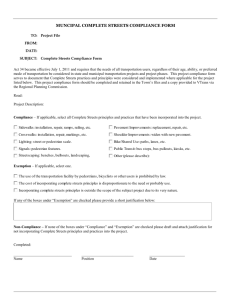

Living_Streets_sub_to_WEC 185.0 KB

advertisement

WEST END COMMISSION EVIDENCE SUBMISSION Response from Living Streets About Living Streets Living Streets is the national charity that stands up for pedestrians. With our supporters we work to create safe, attractive and enjoyable streets, where people want to walk. We work with professionals and politicians to make sure every community can enjoy vibrant streets and public spaces. We welcome this opportunity to contribute to the West End Commission’s consultation into the future of this unique area, particularly in regard to its streets and public spaces. Summary Every day more than 1.7 million walking journeys are made in and around central London. Almost all journeys within central London involve a portion of walking within the public realm and 40% of all journeys are made entirely on foot1. As a result, the West End contains some of the busiest and most crowded streets in Europe, full of people trying to make their way around the city. Such intense activity is part of what makes the West End exciting and vibrant, but is also one of its greatest challenges. It places enormous pressure on transport systems and the public realm and some locations struggle to accommodate the sheer numbers of people. The future success of West End will depend largely on how these pressures are met. In order to safeguard the West End as a world class centre for entertainment and shopping, and to make it a better place for people to live and work, Living Streets recommends: The creation of a network of pedestrian-friendly streets and public spaces, free of clutter, where traffic does not dominate, and people on foot can relax and feel comfortable. A significant reduction in motor traffic volumes, particularly in Oxford Street. The introduction of a 20 mph speed limit covering the whole of the West End. The Challenge Ask any resident or worker in the West End what makes it great, and you will find issues that affect the walking environment at the top of the list: how safe they feel when walking around the area; how attractive their local streets are; and the care taken to maintain the basic quality of the street. Our streets are the one public service everyone – residents, workers and visitors – uses every day. Yet the public realm is often overlooked when considering where public and private investment should be directed. Making the West End a safer, more attractive place to walk and spend time would have significant economic, social and environmental benefits. Conversely, not doing so now could have grave consequences in the area’s ability to compete with other world class entertainment and shopping centres. Economic benefits: in the current financial climate it is vital that the funding for transport projects deliver high returns on investment. Independent research undertaken by the University of the West England on behalf of Living Streets concluded that investment in the walking environment is likely to be of equal or 1 City of Westminster (2011) Westminster’s Core Strategy: Local Development Framework. better value for money than other transport projects and showed positive cost-benefit ratios of up to 37.6 compared to other transport projects2. Social and environmental benefits: the 2006 Eddington Report3 noted that active travel has ‘the potential to provide benefits to the economy and welfare through both reduced congestion and the associated likely reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants, and improved health’. Central London has amongst the worst air pollution in the country. Air pollution averages well over twice WHO recommended maximum levels occur in busy London streets such as Marylebone Road, Kings Road, Earls Court Road and Brompton Road. Ground-based transport accounts for 22% of London’s carbon dioxide emissions 4. The importance of putting pedestrians first is outlined in policy CS40 of Westminster’s Core Strategy which states: “Walking is the most efficient means of movement for short journeys, including those from other transport modes to final destinations. Walking should therefore be prioritised above all others, particularly due to the congestion and high volumes of pedestrian traffic that are experienced in parts of the city, and should also be prioritised in the design and layout of new development.” 5 Pressure on the road network is increasing. There is limited opportunity to increase road capacity and public transport is already operating at full capacity. Therefore, there is an urgent need to encourage modal shift from motor traffic and public transport to active travel modes such as walking and cycling. Living Streets’ recommendations 1. The creation of a network of pedestrian-friendly streets and public spaces. The West End has many fine streets and public spaces that are rightly celebrated by residents and visitors. Sadly, however, narrow crowded pavements, noisy fast-moving traffic, inappropriate gyratory systems and difficult crossings undermine this experience. In fact, very few of the West End’s busy central streets and public spaces have been designed to welcome pedestrians, or to help them get round the city easily and efficiently. Even in the busy central locations which are full of people on foot, pedestrians still face narrow crowded pavements, noisy fast-moving traffic, inappropriate gyratory systems, and difficult crossings. There are too few pleasant walking routes which reach all the way from one destination to another, without interruptions, obstacles, or missing links. We would like to see the development of a pedestrian network in Central London – a network of pedestrianfriendly streets and public spaces, free of barriers to walking and free of traffic domination, where people on foot can relax and feel comfortable. The sort of improvements to the streetscape we recommend are wider pavements free of obstacles and obstructions, pavements which have priority over side-roads and delivery lanes; more and better crossings located where people want to cross the road; and regular “oases” or resting points for people on foot, with seating and outside tables. The network could be built up on a step-by-step basis, starting with a central hub such as Leicester Square, which already welcomes people on foot. From this hub, it could gradually extend outwards, linking together the Central London routes and destinations which are most important for people on foot – the busy 2 University of the West of England, Bristol, and Cavill Associates (2012) Making the Case for Investment in the Walking Environment http://www.livingstreets.org.uk/sites/default/files/file_attach/Making%20the%20case%20full%20report%20%28web%29.pdf 3 HM Treasury and Department for Transport (2006) The Eddington Transport Study, p.157 para 3.44. London: The Stationery Office. 4 Greater London Authority (2007) Mayor’s Climate Change Action Plan. 5 City of Westminster (2011) Westminster’s Core Strategy: Local Development Framework. pedestrian highways, the main-line stations, the famous squares and meeting points, the principal tourist attractions, the riverside walks, and the great parks. As it expanded, the routes and public spaces which already welcome people on foot - like Covent Garden, Carnaby Street, and the riverside walk along the south bank of the Thames – could be incorporated into the network. The streets and public spaces making up the network would welcome pedestrians and they would be free of traffic domination, encouraging people to enjoy the city and make their way around it on foot. Each new route or destination would be upgraded before it was included in the network, to ensure that it offered a fair balance between the demands of motor vehicles and those of people on foot. This would ensure that people using the network could be confident that they were entering a safe pedestrian environment. Almost certainly, the network would prove enormously popular, attracting Londoners and visitors keen to explore the new pedestrian-friendly routes and public spaces. There would be more people on the streets, staying longer and spending more money. 2. A significant reduction in motor traffic volumes, particularly in Oxford Street. Great streets like Oxford Street, Piccadilly and Charing Cross Road are much more than traffic highways – they are important destinations in their own right. However many of its busiest and most popular streets and public spaces in the West End are still unreconstructed, unwelcoming to pedestrians and – as the Danish architect Jan Gehl described – “dominated” by the demands of motor traffic6. Living Streets believes that reducing the volume of traffic in the West End would have the single biggest impact in transforming it’s currently congested streets into people centered places. The introduction of Crossrail will dramatically increase transport capacity and offers the opportunity to take a new approach to traffic management. There are particular opportunities in Oxford Street. Oxford Street: The quality of the pedestrian experience on Oxford Street is a national scandal. We need a staged pedestrianisation of Oxford Street, if it is to maintain its reputation as a world class destination befitting its status as the country’s most famous shopping street. The number of buses using Oxford Street must be significantly reduced. This should start by concentrating first on routes which are carrying few passengers, and on routes which duplicate each other. Second, as the number of buses is reduced, TfL should look carefully at ways of stopping buses bunching together. It is the long unbroken convoys of buses all the way between Marble Arch and Tottenham Court Road, which intimidate pedestrians and make it difficult to cross the road. Third, taxis should be redirected out of Oxford Street and on to the side-roads which cross it from north and south, encouraging them wherever possible with pick-up points and taxi-bays located at the important junctions with Oxford Street. There are some 38 side-streets entering Oxford Street, regularly spaced out along its whole length, so people would never have to walk too far to find a taxi. 6 Jan Gehl (2004) Towards fine City for People. Gehl Architects 3. The introduction of a 20 mph speed limit covering the whole of the West End. Introducing a 20 mph speed limit throughout the West End would reduce traffic noise and danger and improve the environment for people on foot, while having little effect on journey times for motorists. The government has now made it easier and cheaper to introduce 20 speed limits, the benefits of which include: Safer streets - A pedestrian struck at 20 mph has a 97% chance of survival. At 30 mph the figure is 80%, falling to 50% at 35 mph. Putting people first – A 20 mph limit helps create an environment in which pedestrians feel confident about crossing the road and it is quiet enough to hold a conversation. A 20 mph speed limit immediately puts people first by ensuring that traffic is travelling at a speed slow enough to adapt to pedestrian presence. Improving sociability - Heavy traffic damages communities – and the speed of traffic plays as great a role as its density. Research from Basel in Switzerland has shown that the sociability of streets increases as street traffic speeds decrease. At 20 mph, even a heavily-trafficked street instantly becomes easier to cross, less noisy, and more sociable. Encouraging walking - A 20 mph speed limit in built-up areas allows for the safe mixing of motorised and non-motorised modes of transport, and makes it easier for pedestrians and cyclists to enjoy the same direct and safe routes for their journeys as motorists. By adopting this ‘level playing field’ approach to speed limits, local authorities can encourage pedestrians to take to their streets. In Munich, with a "pedestrian-friendly city" policy, 80% of the road network has a 30 kph (19mph) limit. Tom Platt London Coordinator Living Streets Tom.platt@livingstreets.org.uk