Important Questions In Environmental Ethics

advertisement

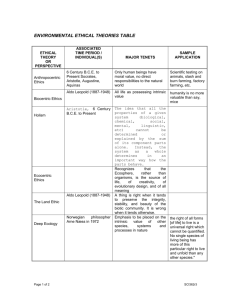

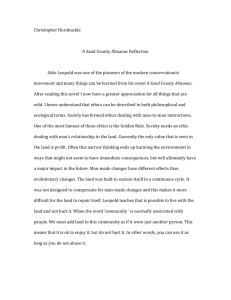

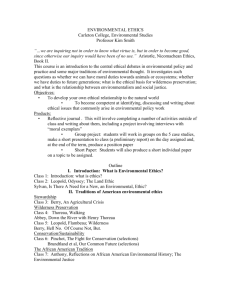

Introduction to Environmental Ethics ~ Key questions regarding diagnoses & prescriptions Bron Taylor The University of Florida www.brontaylor.com Key Questions In Environmental Ethics 1) Diagnosis: What is/are the cause/s of environmental decline (diagnosis). 2) Prescription: How to slow, halt, and reverse these trends? 3) Which environmental ethics are best? Individualistic/holistic? 4) Who/what has standing? Humans? Sentient creatures? Plants? Ecosystems? 5) What trumps what? (see above) Types of diagnoses (sometimes seen as related and mutually reinforcing) Transformations in technology and livelihoods / modes of production. E.g.: Agriculture/domestication. Capitalism/Industrialization. Population growth related. Maladaptive human-social relations precipitate decline. E.g.: injustice, hierarchy, patriarchy Maladaptive (bad) ideas and corresponding practices. E.g.: religious, philosophical, economic, ethical, scientific Population dynamics (boom/bust), perhaps exacerbated by the above. E.g.: carrying capacity and biology-focused explanations Key Questions In Environmental Ethics ~ on ideas What role (if any) does religion, and especially religious ideas, play in environmental decline? Can religion be part of the solution? Is western religion the culprit? Critics cite 4 anti-nature tendencies in western religions 1) Domination of Nature Genesis: God commands humans to "fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing...” 2) Rejection of animism and pantheism Animists believe that every part of the environment, living and non-living, has consciousness or spirit. Therefore, all beings deserve reverence. Pantheists believe the world (or cosmos) as a whole is divine. Therefore nature is sacred or holy and people should have reverence for it. 3) Wilderness is cursed; Pastoral, agricultural, and City landscapes are Holy, Promised Lands 4) The sacred is beyond the world - earth is devalued in favor of heavenly hopes Lynn White (1973) Yet a man-nature dualism is deep-rooted in us. . . . Until it is eradicated not only from our minds but also from our emotions, we shall doubtless be unable to make fundamental changes in our attitudes and actions affecting ecology. The religious problem is to find a viable equivalent to animism (White 1973: 62). Our traditions promote a care-giving stewardship not domination of nature. (Noah story) Some admit the general destructive tendency, but say: Minority "traditions within the wider tradition" are nature-beneficent. But these religions are currently mutating. Some new forms have emerged that are concerned about the environment. Will they prove to be adaptive and survive? Is western philosophy -another culprit? Critics blame its “dualism,” viewing humans as separate from and superior to nature. Rene Descartes is often blamed Rene Descartes (1596-1650): believed that animals have no minds and cannot suffer Humans have minds and souls, they are different from animals So for Descartes, HUMANS are separate from nature and superior to it. And the natural world became an objectified "thing." Some critics say this objectification of nature is a key to science and ‘progress’ Francis Bacon is also blamed Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was the father of the Scientific method. Critics say he promoted a view of nature as a machine. Many passages reveal that he likened nature to women and slaves, and implied all should be bound into the service of men Many scholars think such thinking shaped the anti-nature views of Judaism and Christianity, and thus warped human-nature relations in the west The main divide in both religious and secular environmental ethics: Individualism v. Holism Both holistic and individualistic environmental ethics address -- Whose interests count? Whose interests must we consider? I.e.: Who has ‘standing’? Human Individuals? Anthropocentrism: The environment is valuable to the extent is useful or necessary for human well being Usually "rationality" or some "intellectual" criterion is critical in the West for moral standing Not much new here in the overall approach Who has standing? Sentient animals? Sentient animals are those who can experience pleasure and/or pain Jeremy Bentham: early utilitarian theorist, provided a basis for extending moral standing beyond humans Peter Singer: "Animal Liberation" theory provided a utilitarian argument pro-Animal Liberation Who has Standing? Entities with ‘Interests’ Living entities that have "interests" -- a good that can be harmed -- have moral standing Wm Blackstone: Humans do, and have a right to a liveable environment, upon which all other rights depend Joel Feinberg (1974): Those with conscious wishes, desires, hopes (etc.) have interests, and HBs have duties to them. Animals and unborn humans have such interests. Christopher Stone (1972/74): Individual natural objects, including trees, can have standing Conservator/trustee notion analogous to mentally deficient humans Tom Regan: Animals who are "subjects of a life" have a "right" to that life. Problems with individualistic approaches: (1) Animal Liberation: How can you measure pleasure/suffering a perennial problem with utilitarianism (2) Animal Rights: boundary of moral considerability is very restrictive (3) Why base moral standing of non-human beings on human traits? (Why do animals matter only if they are “like us” in some way we think is important?) Problems with individualistic approaches: (4) How can we determine what the "interests" of a living thing are? who should decide? (5) Individualistic approaches provide no basis for prioritizing concern for endangered species The trend in environmental ethics seems to be toward holistic Approaches -- their basic idea: The whole is greater (and more valuable) than the constitutive parts (it’s the ecosystem stupid!) 3 Holistic Approaches Biocentrism life-centered ethics Ecocentrism ecosystem-centered ethics Deep Ecology ‘identification’ and kinship ethics Excursus ~ Aldo Leopold’s Ecocentric ‘Land Ethic’ Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) This excursus provides key quotes from Leopold. Leopold’s Ecocentric Land Ethic "All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts.” The Land ethic “enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land” Note: ‘the land’ = all life, and all that constitutes it. Therefore, with a land ethic: Precursors: A land-use decision "is right when it tends to preserve – Baruch the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends Spinoza otherwise.” – Henry David Thoreau – John Muir For Leopold Ethics evolve, and they involve self-imposed limitations on freedom of action derived from the above recognition • Precursors: – Baruch Spinoza – Henry David Thoreau – John Muir ETHICS CAN AND SHOULD EVOLVE. In Leopold’s words: “I have purposely presented the land ethic as a product of social evolution because nothing so important as an ethic is ever ‘written.’ . . . The evolution of a land ethic is an intellectual as well as emotional process.” AS ETHICS EVOLVE THEY NATURALLY CHANGE OUR AESTHETHICS (SENSE OF WHAT IS BEAUTIFUL) AND OUR EMOTIONS (WHAT WE FEEL AFFECTION FOR AND CONNECTION TO). Leopold’s promoted humility and feelings of ‘kinship’ with non-human organisms. In this, he was inspired by Charles Darwin. "It is a century now since Darwin gave us the first glimpse of the origin of species. We know now what was unknown to all the preceding caravan of generations: that men are only fellow-voyagers with other creatures in the odyssey of evolution. This new knowledge should have given us . . . a sense of kinship with fellow-creatures; a wish to live and let live; a sense of wonder over the magnitude and duration of the biotic enterprise.” FOR LEOPOLD, THE VIRTUE OF HUMILITY NATURALLY FLOWS FROM AN EVOLUTIONARY / ECOLOGICAL UNDERSTANDING: The Land Ethic: "changes the role of Homo Sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the [land-] community as such." For many, Leopold provides compelling ground for valuing and defending biological diversity "The outstanding scientific discovery of the 20th century is . . . . the complexity of the land organism. Only those who know the most about it can appreciate how little is known about it. The last word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: 'what good is it?’” Aldo Leopold articulated an ecological metaphysics of complexity, interconnection, and mutual dependence. This was a part of an all-encompassing organicist metaphysics. In A Sand County Almanac he spoke of the land as an organism, as alive. “The land is one organism. . . . [and ] the outstanding discovery of the twentieth century is . . . [its] complexity. If [we understand the] whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not.” Leopold’s ‘Round River’ parable: Wisconsin’s Round river flowed into itself "in a neverending circuit" symbolizing "the stream of energy which flows out of the soil into plants, thence into animals, thence back into the soil in a never ending circuit of life.” The parable reflected Leopold’s organicist metaphysics; even bordering on a Gaia-like pantheism: "The land is one organism. Its parts, like our own parts, compete with each other and co-operate with each other. The competitions are as much a part of the inner workings as the co-operations. You can regulate them -- cautiously -- but not abolish them.” “If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog in the wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering.” Leopold also spoke in a melancholy way of the penalty of an ecological education: • “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on the land is quite invisible to the layman” • Many with such an education know exactly how he felt. Leopold was also a social/cultural critic: . . . WHILE URGING PRUDENCE HE NOTED, IN CONCERT WITH MUCH DARK GREEN RELIGION, THAT ABRAHIMIC RELIGIONS ARE AN OBTACLE TO A LAND ETHIC: Misguided religion and philosophy work against the emotional ties, felt kinship, and the sense of loyalty to the land that his ethic demands. But why? "Conservation is getting nowhere because it is incompatible with our Abrahamic concept of land. ‘No important change in human conduct is ever accomplished without an internal change in our intellectual emphases, our loyalties, our affections, and our convictions. The proof that conservation has not yet touched these foundations of conduct lies in the fact that philosophy, ethics, and religion have not yet heard of it.’ “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” Leopold’s “land ethic” ~ practical applications • "The whole world is so greedy for more bathtubs that it has lost to the stability necessary to build them, were even to turn off the tap. Nothing could be more salutary at this stage than a little healthy contempt for a plethora of material blessings.” • "We have no land ethic yet, but we have at least drawn nearer to the point of admitting that birds should continue as a matter of biotic right, regardless of the presence or absence of economic advantage to us.” • “A parallel situation exists in respect of predatory mammals, reportorial birds, and fish-eating birds.” Leopold continued that the development of a land ethic that values predators, is "still in the talk stage. In the field the extermination of predators goes merrily on.” THINKING LIKE A MOUNTAIN In this, his most famous essay, which sought to inspire respect for predators, Leopold began by asserting that “mountains have a secret opinion about” wolves, adding, “My own conviction on the score dates from the day I saw wolf die.” Then he wrote: – “We were eating lunch on a high rimrock, at the foot of which a turbulent river elbowed its way. We saw what we thought was a doe fording the torrent, her breast awash in white water. When she climbed the bank toward us and shook out her tail, we realized our error: it was a wolf. A half-dozen others, evidently grown pups, sprang from the willows and all joined in a welcoming melee of wagging tails and playful maulings. What was literally a pile of wolves writhed and tumbled in the center of an open flat at the foot of our rimrock. THINKING LIKE A MOUNTAIN (cont.) In those days we had never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack, but with more excitement than accuracy; how to aim a steep downhill shot is always confusing. When our rifles were empty, the old wolf was down, and a pup was dragging a leg into impassable side-rocks.” "We reached the old wolf in time to watch the green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever sense, that there was something new to me in those eyes -something known only to her and to the mountain. I was a young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, than no wolves would mean hunters' paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.” Leopold’s ethic has decisively shaped the American conservation movement, and has become increasingly influential around the world. The next slide shows the land ethic as a panel at a large exhibition at the 2002 United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development. ‘A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community’ Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic, present in the exhibition, Voyage to Antarctica, at the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg (2002) Leopold’s wide influence is due in part by his ability to write in a way that evoked in his readers a sympathy for life beyond their own species. This ability to empathize was viewed by Darwin as an adaptive outgrowth of evolution. That this capacity is a part of the human repertoire both helps to explain the global presence of dark green spirituality, as well as its of potential as an eco-political force. Back from excursus to Holism more generally . . . Lovelock’s holistic planetary ‘Gaia hypothesis’ Lovelock argued in Gaia: A new look at life on earth (1979) that the biosphere is a self-regulating living system that maintains the conditions for the perpetuation of life Although not intended as an ‘ethics,’ a biospherecentered (large-ecocentric) ethics has been deduced from it, claiming: People ought not degrade and imperil this wonderful system, upon which all life depends. Holistic Approaches -Key criticism: Individuals get hurt when you ignore them in favor of wholes This is the key criticism of all ends-focused theories In environmental ethics, the common charge is of "ecofascism"! Despite all the various points of view, something new does seem to be evolving in the emergence and evolution of “environmental ethics,” both secular and sacred, involving The Gradual Extension of Moral Concern Beyond our Own Species