Edited and annotated OUR ILMINGTON by John Purser

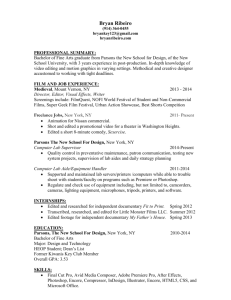

advertisement

Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Purser biography ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Links with Handy family of Ilmington ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Census entries ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Re-ordered full transcription of document ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Ilmington background ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Family .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Siblings ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Father’s job - Quarryman ............................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Father’s Clothes........................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Domestic life.................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Layout of the houses ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Baking .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Bedrooms ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Water supply and washing ........................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Clothes ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 World of work ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Leaving School and into work ................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Wages ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Food growing ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Food self - reliance .................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 The allotment ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Swedes and mangolds in the winter .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 Ploughboy .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Planting - dibbers ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Planting – sowing by hand ........................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Bird scaring ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 14 Harvest ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 14 Long hours ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Mowing ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Singing ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Machinery ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 16 Raking .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Rick making ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Gleaning................................................................................................................................................................................................. 18 Flailing ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 18 1896 summer shortages .......................................................................................................................................................................... 19 Animals .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 20 The Shepherd ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 20 Pigs ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 21 Pigs into the fields ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 Selling the pig ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 22 Killing the pig ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 22 Bees and fowls ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 22 Donkeys..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 23 Recreation ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Bicycle........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 24 Sports and games ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Education ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 25 Schoolhouse ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 25 Books ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 25 Religion .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 26 Methodism ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 26 Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 1 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Marriages ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 26 Death ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 27 Rich and Poor ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 28 The Squire – Mr Philip Howard, & Foxcote House ................................................................................................................................ 28 The Manor House ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 29 The Rector and his family ......................................................................................................................................................................... 29 Rectory treats ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 30 “Higher class” ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 31 Transportation -Tom, the one-armed village carrier .................................................................................................................................... 32 The outside world intrudes ........................................................................................................................................................................... 33 Imports from the colonies ......................................................................................................................................................................... 33 Working on the railway ............................................................................................................................................................................ 33 Agricultural depression ............................................................................................................................................................................. 33 Moving to the towns ................................................................................................................................................................................. 33 POSTSCRIPT .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 34 Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 2 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. INTRODUCTION This document was scanned in 2012 from a loose type-script copy, dated 1958, belonging to Ms. Nettie Edwards who obtained it personally from Miss Ibbotson in the village of Ilmington. 1 The section headings in this transcript are editorial, and the order is original to the account. Purser biography John Purser was born about 1879 in the village and left school aged 13 in 1891, going into farm-work. He left the village, by carrier’s cart, about 1899. He worked at Chilvers Coton for the railway, and lived in Nuneaton. Apparently in September 1906 he married Ada Wooton in Nuneaton, according to an on-line website by the Crellin Family. 2 He fathered a child about 1908 (and calling him “Lloyd George”! 3). His wife, Ada, also died in 1908 and he re-married to Annie Whittington in Leicester in December 1913, having a child with her too. They emigrated to New Zealand on the “Remura” on 20th Sept 1920 with his wife and children from Southampton, and were listed as being resident in Upper Hutt in Main Street as a dairy farmer in 1928; in Melrose Street in 1938; at 240 Main Road in 1946; and at 3 Bracken Street, Heretaunga in 1954 & 1957. He revisited the village on several occasions, the last being about 1921. His account is of interest because during his described childhood he lived a few doors away from the Editor’s great great grandparents in Campden Street, Ilmington. 2 The David Crellin Family tree on Ancestry.co.uk gives full details http://trees.ancestry.co.uk/tree/36671931/person/18971733207 3 Living 1981 at 473, Karaka Bay Road, Miramar, Wellington. 1 Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 3 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Links with Handy family of Ilmington He was in Lower Hutt in 1934 when he heard Shepherd Walton Handy’s Christmas radio broadcast from the village. This was reported in the Nottingham Evening Post of January the 3 rd, 1935: N.Z.Link with the “Cotswold Shepherd” - Boyhood friend hears his voice - Christmas broadcast sequel. When the old shepherd in the Cotswolds broadcast a Christmas greeting to the British Empire on Christmas Day, no listener of the many millions was more moved than Mr. J. Purser, and old resident of Upper Hutt, near Wellington, N.Z. Mr. Purser was born at Ilmington, the village of the old shepherd, who broadcast. He thinks he is the only person in New Zealand who is a native of Ilmington. No trace can be found in New Zealand of the brother of the old shepherd of whom he spoke and whom he asked to write to him if still alive. A LARGE FAMILY “It was as if the broadcast was specially addressed to me, “ said Mr. Purser “and as if the link once severed had been forged anew. “I believe the name of the old shepherd is Handy. I did not just catch whether his Christian name was Walter. “If it was then I knew him. There was a large family, and I was brought up with them. I lived in Ilmington from 1870 until 1899. “I have been back there several times, but not for the last 14 years.“I have cabled the villagers telling them of my pleasure at the broadcast, congratulating them upon their success, and sending them Christmas greetings.” Note. – the name of the shepherd was Walton Handy. He said that a brother of his left Birmingham in 1907 for Auckland, N.Z. where he was setting up on his own. He did make contact with the Handy family in New Zealand, specifically Joshua, who had emigrated on the Athenic on 27-3-1913 into Wellington, New Zealand, after a time resident in Birmingham. In January 1943 Josh’s wife Blanche wrote home: “We had a letter from Mr Purser 4 he asked us to go and see them again, but we cannot get benzine enough and when you are not well TP home seems the best place” This Handy family is that of the present author, and the link is the cause of the genealogical interest that caused this document. 4 TP PT Nettie Edwards has his Autobiography of life from Ilmington to New Zealand. It is interesting to see that they all kept in contact. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 4 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Census entries The following two census returns illustrate his family: 1881 census – Campden Street, Ilmington. District 4. Schedule 68. Robert James Purser Head Married 35 Agricultural labourer Born Ilmington Mary Purser Wife Married 29 William Spicer Step son 13 Agricultural labourer Born Brailes Mary Purser Daughter 7 Scholar Born Winderton James Purser Son 6 Scholar Born Winderton George Purser Son 4 Born Ilmington John Purser Son 2 Born Ilmington Born Brailes 1891 census – Campden Street, Ilmington. District 7. Schedule 146 Four room house James Purser Head Married 48 Agricultural labourer Born Ilmington Mary Wife Married 40 James Purser Son 16 Agricultural labourer Born Brailes George Purser Son 14 Agricultural labourer Born Ilmington John Purser Son 12 Scholar Born Ilmington Ann Purser Daughter 9 Scholar Born Ilmington Fredrick Purser Son 4m Born Brailes Born Ilmington 1901 sees him in lodging with an American family and his brother: 1901 Census – Edward Street, Chilver’s Coton village, Warwickshire. Anne Round Head Grace Round Marr 35 Cole Shropshire Dau 10 Maine, America Annie Round Dau 8 Maine, America Edward Round Son 6 Clee Hill, Shrops. Florence Round Dau 1 Nuneaton James Purser Boarder S 26 Railway Porter Brailes. ????? John Purser Boarder S 22 Railway Porter Ilmington. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 5 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. 1911 saw him still in the Chilvers Coton district, but living at 81, Chevnal Street (?) in Nuneaton with siblings and a child - whilst working for the London and North West Railway.: 1901 81 Chevnal Street, Nuneaton. John Purser Head Wid 32 Railway signalman Ilmington Annie Purser Sister Single 29 Housekeeper Ilmington Frederick Purser Brother Single 20 Railway Goods Porter Ilmington Alfred Harry Goodwin Cousin 18 Domestic Gardner Bodymore H. Staffs. Lloyd George Purser Son Single 3 Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Nuneaton. Page 6 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Re-ordered full transcription of document Ilmington background “The village of Ilmington lies on the northern edge of the Cotswolds, in the county of Warwick. Family My father was an agricultural labourer there. My mother came from the village of Brailes, in Oxfordshire. She worked at a farmhouse, whence she was married at twenty-one, my father being twenty-six, about the year 1872. My father had six pounds to get married with. My mother had very little; but her mistress came to her help because she had been a good servant, found them a house, and gave them a little furniture. Siblings There were four children before me. Bill, the eldest, worked as a farm labourer, until he enlisted in the Warwickshire Regiment, and was sent to India. There he took ill, and was brought home to a military hospital, where my mother had not the fare to visit him before he died. My elder sister, Polly, after a few years domestic service, married in the village, and died with her first confinement. Jim and George, left home to seek employment in a distant town. My two elder brothers, My younger sister, Annie, went into domestic service. My youngest brother, Fred, joined the Police Force. Father’s job - Quarryman My father, for a few years, was quarryman on the estate. Stone was found on the hills in different places, eighteen inches or so deep. It was loose and did not need blasting, but was prized out with sharpened iron bars, broken into large lumps and wheeled to stacks nearby, three feet high and so many yards square, making a hundred or more square yards. making sure of his measure. The County Surveyor would come along and buy a particular lot, after Small hauliers with one horse came from the nearby-villages, and carted the stone to the country roadside, where the stonebreaker broke it small enough for the roadmender to repair his roads. There was no steam roller, and so the roads remained rough. The stonebreaker's job was a lonely one, on the grass verge of the road all day. He must first break the stones down with his large hammer, and then use a small, blunt, double-headed one to finish them off. It was not as easy as it looked. He had to make sure of his mark, or he would make slow progress. Often, he would sit on Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 7 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. part of his broken heap to get closer to the work, and so ease his back. Occasionally he would get a passerby to stop and talk. He would find a sheltered spot in the hedge for his midday meal of bread and cheese and bottle of cold tea. When he started for home, it took him a while to find his road legs; and then he would hasten to the chimney corner and his warm meal. It was usually an old man who had to take such work. The pay was not as much as a labourer's, unless long practice had made him quick. It was paid for by the yard, and the stones must be of even size. To bring such stone to our village, it was necessary to come down a dangerously steep hill, so a large boxful was hung with a stout chain to the axle of the cart, to ease the horse and steady the load downhill. One man loaded too heavily, and in descending the hill lost his life; another got his leg broken. When the great granite quarries of Leicestershire and North Warwickshire opened, and railway transport became general, it put a stop to the local quarrying, and the stonebreaker and haulier found safer work. Father’s Clothes Dad had the same black wedding coat twenty-five years afterwards. mates said, "Here's Jimmy coming out in his black cloth". When he finally wore it to work, his When he was young, he used to have to go to bed early on Saturday night, so that his smock could be washed for Sunday. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 8 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Domestic life Layout of the houses In the village homes, one large room opened straight from the street or garden, with perhaps a small pantry where food and cooking utensils were kept. Baking An oven was built into the chimney corner, with the oven door so arranged that the escaping smoke would go up the house chimney. This door was no more than a heavy block of wood, with a handle for each hand, made to fit closely, although it might have to be packed with cloths to keep the heat in. The oven was shaped like a big, upturned dish, about four to six feet across inside. When it was empty, children playing hide-and-seek would climb into it, the door being just big enough for a child to creep through. When we became "little smallholders" with our own wheat, my mother tried her hand at baking bread in an oven of this sort. The fire was made straight on the oven floor, with small branches. (These branches were the trimmings of ash poles from the woods, and were sold in large faggots bound with wire, about four feet long, weighing about half a hundredweight, and sold by the score bundles.) The greatest difficulty was to know when the oven was hot enough. Then all the ashes had to be scraped out clean, and the bread placed In quickly with a long-handled pole. There would be ten or more loaves; a bacon and potato pie; some scraps of pig-meat; and a dough cake with currants. If the oven was hot enough, and the bread taken out at just the right time, all was well, and very thankful we were, Mother and I, a school lad. If the oven was not hot enough, the bread would be heavy, or "sad"; but we had to make the best of it. My mother was relieved when the local baker, seeing his trade diminishing amongst those who had wheat, offered to bake for us at a ha'penny a loaf. The miller called and took three bushels of wheat at a time. Some families paid by allowing him to take a portion of the meal, but not us: Dad would pay. We needed all for ourselves and our two pigs. We grew barley, and half a ton of potatoes, besides small vegetables. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 9 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. It was now my job to take, once a week, half a bushel of wheat to the baker to bake our bread, and currants, sugar and lard to make us dough cake. We would get a dozen loaves returned to keep us a week or more. When shut down in a large, glazed earthenware pan, it would keep sweet the whole week. Bedrooms The one or two bedrooms of the thatched cottages were in the roof, and were open to the rough rafters, which were branches cut straight from the tree. We easily bumped our heads. The only light and ventilation was from one small window, two foot by two foot six. In such cramped conditions, if one member of the family got influenza, others were sure to catch it. One lad who was asked about his mother's health said she had got " 'en flew out of the window". Water supply and washing There was no water supply to the village houses. A few lucky ones had a well, or a pump. In a dry season, the old pump would sometimes refuse to work, until he had a "prime. This was done by pouring a jugful down his throat, and working away at his arm, till he was eventually coaxed to work. One must keep at it till all had had enough, or he'd go on strike again quickly. We were fortunate, we had a well, though sometimes it was necessary to let down the bucket on the end of my older brother's shepherd's crook. In most other cases, water had to be carried a long distance, and this fell to the hard-pressed housewife during the day, not with a pitcher, like the Samarian woman, on her head, but with a yoke and two buckets. Such yokes were well made and fitted comfortably on the shoulders; even then, it was a heavy job for mothers. At one house where we lived for a time, it was my job to carry sufficient water on Saturday to supply us till Monday, and store it in a large glazed vessel holding several gallons. Washing was done on a bench outside in a large zinc vessel. All heating of water was done in a big iron pot. Even when empty, it was as heavy as a woman could lift. Clothes We could buy an extra pair of boots instead of our hobnailed ones, which made a rare clatter going up and down the stone steps of the church. They had to be cleaned after late Saturday nights, coming from the farmyard. How much I used to wish I had a pair like my farmer-employer’ s boys', as they came squeaking along the nave. Our corduroy pants sometimes had to do over-time weekdays and Sundays too, before we could buy more, when the old ones gave notice to leave. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 10 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. World of work Leaving School and into work Leaving school in 1891, at 13 years of age, I began work leading or driving horses, four in a team, with a carter or ploughman. Three shillings a week! That was a lift to Mother's weekly budget. At one time, there were four of us to get off to work before seven in the morning. Our parents would rise early to make the fire. The kettle was boiled, and our tea bottles filled for the day; .bacon was cut from the flitch and fried for breakfast; and then a heaped-up plateful of bread dipped in fat was made up for our lunches. But the Bible reading and prayer were never neglected. Wages There were then three of us, and Dad, on regular work. Dad earned ten shillings a week, my elder brother eight shillings, and we two younger ones three shillings each. parents apportioned the total twenty-four shillings. shillings to be gathered; We would listen with painful interest while our There was the quarterly house rent of twenty-five and something must be set aside for the grocer, when he came with his horse-van from Shipston-on-Stour. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 11 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Food growing Food self - reliance With our own corn from one and a half acres of allotment enabling us to get two weaner pigs to feed, kill and hang up in our chimney corner, we began to feel like smallholders, or farmers, with plenty to eat. The allotment land had to be cultivated, and this we did chiefly at night, after our daily work, from 6.30 p.m. till near bedtime, 9 or 10 p.m. On this land we grew 35 to 40 bushels of wheat. The allotment Twenty acres of land taken over by the village labourers as allotments were a great asset to the industrious. They not only provided food, but, in cases of unemployment, temporary work. The men could work them even in winter, instead of loafing around in the blacksmith's shop. One day, snow on the ground, Dad was going by, not daunted, to see what he could do on the allotment till he could resume his usual work. "Where are you going, Jimmy?" came a voice from over the half-door of the blacksmith's shop. "To my land." "But it'll do no good digging snow in." "You go, Jim, " came from the blacksmith, "It won't hurt. " When fine weather came, and he could go to his employment, Dad had part done, ready for the crop. It was a busy time for Mother at home, now Polly had gone out to service, for she looked well to her household. But she was happy because she had plenty of food for her growing family, and as the Old Book says, her husband was known in the Gate. The plain but wholesome food stood us in good stead. Swedes and mangolds in the winter To feed the cattle and flocks of sheep during the long winters, much cultivation had to be done, to supplement hay and oaten straw. Swedes or mangolds had to be hoed and singled to keep down the weeds. Then, in the late autumn, before the severe frosts, they were pulled, thrown into heaps, and covered with soil six to nine inches deep to keep them from being frozen. I remember Fred who, though crippled, worked and brought up a large family. His body was bent, and never from youth could he walk upright, yet he was as useful as most men in the woods and on the farm. A job he Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 12 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. liked in its season was singling and hoeing swedes. His bent form lent itself to the work and he could leave more able-bodied men behind. When the swedes were uncovered, one heap at a time, they had to be cleaned with large knives made from old scythe blades. Sometimes boys or women-folk were employed. It was cold, uncomfortable work, standing under straw-thatched hurdles for protection from the snow, rain and biting winds; yet poverty drove a few to it. One poor woman I knew did it for two or three winters. She was deaf and lived alone. She would wrap her legs in some sort of leggings for protection from cold and wet, and stand there for hours, with a swede in one hand and knife in the other, cleaning, ready for the mill. After a few hours up there in the bleak wind, with only a sack thrown over our shoulders, we often ate a clean piece of swede to tide us over till we reached home. When we descended the hill at night, coming down into the sheltered village, our faces were all aglow, and finger-tips and toes tingled so that there was no need to sit by the fire. Ploughboy A boy often became a ploughboy on first leaving school. It was a leg-aching job, trudging along beside the horses, the boy doing his best to keep them going, cracking his whip and talking encouragingly. lads!" "Gee up, my Some of them would be lasses; it was all the same. He got two or three pounds of dirt to his boots, all thrown in for sixpence a day, with only a short stop to eat his bread and cheese, or bacon, with a bottle of cold tea. Then shut off at three o'clock, attend to his horses, and home for his dinner, so hungry that nothing came amiss. Planting - dibbers Dibbers were used when it was time for planting the corn. These were shaped like a big, inverted pear, with a pointed steel cap to pierce the ground. Some were small, but where a large field was to be planted, an experienced man would use two long-handled dibbers, and walking backwards, would make the holes, two at a time, as he moved. Planting – sowing by hand Then came the women, with little calico bags tied round their waists, to drop in the corn. It was tiring work, done in wintry weather, for which they might get a shilling a day. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 13 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Bird scaring I could now work as "bird-scarer", chasing the rooks off the newly-sown fields. We would leave home early, Dad and my two brothers for the farm, and I for the fields. I was warmly wrapped in clothing cut down from my older brothers' cast-offs, and had a sack, with holes for my head and arms, thrown over me. From a distance, one could not have told me from a built-up trilby hat, in the middle of the field. "momrneck" of old bags over sticks, and a There I sang the hymns familiar in our Methodist home - "Only an Armour Bearer". My only armour was a stick like a shotless gun. I had a few dry sods in the hedge built up as a fort to protect me for a while, till forth I took myself again. No sooner had I got to one field, than the rooks would be there at the next. It had to be a constant vigil in bitter, biting winds the whole day, till I saw them take flight at dusk. I used to watch the rooks building their nests in a clump of very high elm trees. Such a talking and a chattering went on. How they started building the nest was a mystery to me, with the twigs laid so that they did not fall before the foundation had been made. It was rare to come across a nest blown down, and then it was usually an old one which had been discarded. Clappers, too, were used to scare the birds off the newly-planted corn. These were three oaken boards, six inches by four, tied together loosely with a thong, the middle board having a handle. They created a great clatter when they were shaken. I earned sixpence a day; the sixpence for Sunday my parents allowed me to keep. Harvest One of the greatest sights was a field of wheat being cut. The farmer would take on as many families as he could, and it was beautiful to see them stretched across a twenty acre field, each taking their allotted acre or two as their part in getting the harvest gathered. The father slashed away with his cutting hook, in his other hand using a wooden hook to hold the wheat in position. One of his school-age children would be making bands from a handful of wheat straw, and laying them to receive the sheaf. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. The mother would come later Page 14 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. from home with a basket of food - broiled bacon, new potatoes, currant roly poly pudding, and a large can of tea. No king ever enjoyed his table as we did on those days, sitting in the open, or under the shade of a hedge. Long hours The school holidays were arranged with the farmers, to coincide with the ripening harvest, for everybody must lend a hand. That was imperative when all had to be gathered as quickly as possible. Even then, it took several weeks, working from six in the morning till seven, or later, in the evening. It was a weary tramp home at night, but there was a feeling of happiness as the families called to one another across the widening distance. When I was nine years old, and my older brother was laying bands for Dad to tie up the sheaves, a single man asked if he might have me to lay bands for him. He paid me threepence a day. The farm labourers took pride in their work, and did not like change. In harvesting, the sickle gave place to the fagging hook and scythe. They in turn gave place to the mowing machine and reaper with its large sails of six, the third one made as a rake, to rake the sheaf off neatly out of the way, to be tied up later in its own straw band and stooked, that is, stood up six or eight sheaves together, to dry and harden the wheat or oats. The old scythe mowers in the hayfield used to say that the aftermath would not come away as quickly after the mowers as after the scythe. The mower pinched it off; it was not a clean cut. Mowing Mowing was a strenuous job, but some delighted in it. It needed skill rather than strength, though many men were not equal to it. To keep a keen edge on the blade and be a successful mower was an art. Singing When time came for a break, one, Tom, used to say, "Come on, mates, let's go and sit with us legs uphill, and rest us backs." They would sing: "Some delight in hay-making, Some delight in mowing, But of all the jobs that I like best Give me a bit of turnip-hoeing. " Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 15 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Harry, a crippled lad with one short leg, had to use a walking-stick to get to the hayfield with his uncle's dinner. One day, on his way home along the footpath, he had to pass through a flock of ewes and their lambs, growing quite strong by midsummer. Two nice black-faced lambs came near to look at him as he stood, so Harry held his stick out to play with them0 But the ewe mother wasn't going to have that. Down went her head, as she charged from behind, and sent him flying. As he struggled up on his lame leg, she knocked him down again. Machinery In some places there was much trouble on the introduction of farm machinery. The labourers thought it would displace them, and make it more difficult to find full employment. In our village, opposition soon died a natural death when the men saw how much back-breaking work they were saved. In the hayfield, the tedder came to distribute the swathes left by the mower. This did the work of the women with their hay forks, but not as well where the crop was heavy; and it was almost useless after the scythe mower. When once the grass was distributed, it was a good implement to move the hay to let the sun and air in. Raking Afterwards came the horse rake, or side rake, to put it in windrows. This rake displeased the men, for they could not do the work as neatly by hand. The hay often fell apart when they tossed it with their pitchforks on to the wagon-load. But when two people with their hay forks, one each side of the windrow, put it together neatly, first one and then the other, the pitchers with their long-handled forks, one on each side of the wagon, could pick it up more easily and quickly. The man on the wagon could then load it much more safely for the journey to the rick-yard, especially if it had to be taken far. Before the use of the horse-rake, with a seat from which a man or a boy could operate, there were "heel rakes". These were six feet wide, with long half-moon-shaped tines, easily drawn behind, one man to each pitcher. They collected the loose hay, leaving all very clean. They were called heel rakes because they were drawn at the heels as the workers moved forward. They were of triangular shape, with a handle across the apex. Another single piece came forward, for the left hand to hold the rake at the best angle for smooth working around and about, as needed for cleaning up all the loose hay, and bringing it forward to the wagon. The workers slid their rakes backwards to empty them; and then worked over the ground again to leave it clean behind them. The horse rake with a strong lad displaced all that. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 16 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. They had a loading language, well understood, for harmonious loading. When the loader had filled the bottom of the wagon, he would say, "Corners in front". They would then put their forkfuls up, both together, and he would hold them by putting his fork across both. "Between corners" meant one of them put his forkful to bind the corners. Next "Behind the corners", and so on towards the back. Then "Corners behind", and "Between corners". Then "Up in the middle" to bind the load They would then repeat the whole process till it was a very full load. When they wanted to move forward, they would shout, "Hold you, " to warn the man on top. If a young lad happened to be leading the horses and forgot to say, "Hold you, " he soon got some black looks, if nothing worse; for the man might lose his balance and fall. Even a simple job had to have its rules, or serious injuries might result. There was no workmen's compensation in those days. their loading, and would say of a good load, "That will ride safe!" They took a pride in Should a lad driving displace the load by not choosing a level track, or catch a gate-post and dislodge part of it, he soon got into his share of trouble. Rick making Probably the most important man of those times was the one who had the knowledge and skill to build a good rick. Where there used to be perhaps thirty to forty-ton ricks of hay, it was no haphazard job. Much depended on how it was handled right from the swathe. It looked simple, but let an amateur try it and he'd soon be running for stout posts to prop it up. The sides were neatly pared with a long-handled blade, and it was then carefully thatched, with eaves cropped to shoot off the rain. One of the best sights in those days was the rickyard of well-built ricks. If a farmer was particular about his hay, it made much better feed for his stock in winter. But some were not; they would gather it as quickly as possible, and bundle it together anyhow to get it done. Good sweet hay, with a little linseed or oil cake; and swedes put through the hand mill; fed at regular intervals to the beast, which was not disturbed between times; these made all the difference to the time it took to get a beast ready for the butcher. Inferior food never made as prime a beast, or such profitable dairy cows. It was interesting to notice the difference, when bales of hay came to be used. The animal could not eat in such a leisurely way. The hay was tucked together so tightly, in a long twist or roll, that the animal had to grab it, and shake or pull it apart, before swallowing it; whilst the cut and trussed hay, which lay in thin layers, could be taken hold of by the tongue and passed down the throat easily, the animal afterwards lying down to chew its cud in comfort. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 17 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Gleaning After the wheat had been harvested, the womenfolk would ... sometimes ask the farmer to allow them to lease, or glean, the stray ears of corn for their own use. They would carry it home in sheets or large aprons on their heads, like Ruth the Moabite long ago, and stack it, still in the ear, in a corner of the house, till there was a large heap ready for threshing. Flailing A flail was used for thrashing out the corn. This consisted of a handle of tough ash wood, with a swivelled loop for free movement, to which a shorter heavy piece, which would not split, was attached by a thong. A man would swing the flail over his head by the thong, and bring it down on the sheaves of corn laid on the barn floor. It was a winter job, when outside work could not be done. other would bring their flails down on the same sheaves. Sometimes two men opposite each My father once set me to help an old hand, and being inexperienced, I caught him a nasty thud with my flail. "Ah, " said he, "That's how I knocked my father down when I was young. " I was thankful my blow had not been so heavy. The men could be heard bringing their flails down whack, whack, whack, on the sheaves the whole day, till there was a good heap of corn. Then they would bring the drum, which took two men to lift it. It enclosed a fan which blew out the chaff and dust, as the corn dropped down through a narrow, regulated opening. A man must turn the fan at a regular speed, or the grain would not be of uniform cleanness, for a sample to be taken to the market. Chaff-cutting was wearisome work. I used to drive a horse chaff-cutter, which had a great beam attached to a large cog wheel, the horse going round and round on the outer end of the beam, in a circle only fifteen feet across. I got sick of working inside the barn, and as sorry for the horse as for myself. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 18 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. 1896 summer shortages The summer of 1896 was very dry. Hay crops were light, and grazing short. "We had just cleared a field of hay on the Rector's farm when his neighbour, who had a big dairy herd, came and asked the bailiff if he might lease it. The agreement concluded, the farmer said, "I'll soon stock it for you. " He went back to the gate dividing his field from the Rector's and called, "Cub, cub" (Come, come). For the herd, there was no mistaking his language: they would have knocked him down, so eager were they to get through. I was sent off one morning for Stratford, with a few fat sheep; but the roads were so hot and dusty, that when I reached the sale-yard, I was too parched to say whose sheep they were. The clerk said, "My lad, you've got it. " A bottle of soft drink at a shop close by released my throat. We used to contrive to have a few coppers in our pockets for those rare occasions. If crops were poor, it was a bad prospect for the winter, and some farms were not easy to let. belonging to the Rector could be let only in parts for grazing; Two farms so hay had to be made and sold as the best source of income. There were four big ricks. These were kept covered while building with a very large sheet supported by poles and cross-bars, and then thatched : as soon as possible to keep the hay dry. The stacks were cut out in neat half-hundredweight trusses, pressed, tied and sold by the ton, or perhaps by the rick, to a dealer from Birmingham. The dealer would test its quality by pushing a rod, shaped like a half-headed arrow, into the centre of the rick and withdrawing it with a sample. This decided the price he would offer. On one occasion we were very short. We had done a little fencing for one farmer, only ten shillings' worth; and after a few days I was sent the two miles to collect it, to save Dad's more valuable time. The farmer was making any excuse to delay payment, so I asked him to give me seven and sixpence, because of our immediate need. When I got home, my parents did not complain of the bargain. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 19 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Animals The Shepherd In winter, Bill the shepherd would pen his young sheep on the ploughed field, where swedes had been grown and gathered. With Dan to help him, he would move the hand-mill from heap to heap, cutting the swedes up into the big "hods". Bill was a big man; but Dan was very small, and found it difficult to carry the hod full of swedes over the heavy ground. When he staggered into the pen among the older rams, they so resented him that they knocked him down, swedes and all. "Bill, Bill, " he spluttered, "Come and help me!" The shepherd went to his rescue, lifting him out of the mud, and helping him to feed. The previous season's lambs, which had been on the root fields during the winter, had to go to the washbrook, for the soil to be washed from the wool before shearing. This was a heavy job, and had to be done with care, or there was loss of sheep. They were held under a heavy fall of water, at a brook with sufficient fall. Large, long-handled hooks were used to hold them, and they were then guided to safety, while the water drained from the wool. Not all farms had suitable brooks, especially on high plateaus. When a flock of sheep had to be taken some distance, it was usual to take along a big wooden bottle, like a little barrel, holding a gallon or more of cider. It once happened that they forgot the cider, and someone had to return for it. fields: found the full cider bottle; He took a near way across the and was returning in haste to catch up with the flock, when he passed a ploughman. It was a hot day, and the ploughman called out, "Give us a drink!" "Oh, no, mate, it's for the men at the wash-brook. " But when they got there, they found that the wooden bottle vas filled with water, which had been left to keep it from leaking, and not the much-needed cider. So the ploughman laughed last. One summer day, Bill was tending his sheep, while his dog watched that they did not get away. There was no pen, and the dog had driven them into a corner of the field where there happened to be a gateway. While the shepherd was attending to a ewe's feet, a ram looked on till he could stand it no longer. Drawing back a little, he took a determined run at Bill (a man of six foot and fourteen stone), and knocked him full force head first against the rail of the gate. Bill had a ringing head and an aching neck for a while. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 20 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Our flocks were well looked after, and the sheep were large and strong. When the shepherd entered the field with a bag of concentrates, such as oil and linseed cake, there was no need to call them. They would be round the troughs before he was. Pigs One other thing must not be forgotten, the pig sty but a few steps from the door. It must not be thought that the pig is as dirty as it is credited with being. If given the chance, it is as clean as any other animal. When given clean straw, it will usually place it with mouthfuls where it wants, make its own bed and scatter the other about, using one corner of its open yard farthest from its feed trough to relieve nature. We fed our pig well, with barley meal, bran, bean meal and potatoes, all from the allotment. Potatoes were washed clean and boiled in someone else's copper, perhaps two or three hundred weight the same day, and stored in a cask, called an "old stinker", from the brewery at Stratford-on-Avon. On Sunday, some of those who were not in the habit of going to church would often tidy themselves, and go along to their friend's, to see how his pig was getting on; compare notes with their own; taste his rhubarb or parsnip wine; and if they were ploughmen, talk about their favourite horses. The pigs were the labourers' greatest asset; only those who had allotments could keep them profitably. They were bought from the farmers as weaners. One of the first that Dad bought, he brought home in a sack. It jumped over the sty wall in the night, found its way back to the farm, and was outside the yard door when Dad arrived for work next morning. Pigs into the fields If boys were available before they returned to school after the holidays, the farmer would sometimes get them to take his pigs into the field and mind them there, to feed on the ears of corn left behind. That fell to my lot on two occasions when I would be ten or eleven years old. I was not sorry, then, when school started, for it was a dreary job if the weather were cold. I liked the pigs all right, and used to give them names. Sometimes I picked up the best ears of wheat, rubbed them in my hands like the Disciples, and blowing the chaff away, tossed the good wheat into my mouth. Robert Bloomfield knew something of this occupation in 1800, when he wrote "The Farmer's Boy": "No more the fields with scattered grain supply Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 21 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. The restless, wandering tenants of the sty. From oak to oak they run with eager haste And wrangling share the first delicious taste Of fallen acorns, yet but thinly found, Till the strong gale has shook them to the ground. One season, an older brother took the pigs out, and with a long pole shook the trees. The pigs, he said, soon knew the oak trees as well as he did.- Acorns were good food, and the pigs liked them. Selling the pig By 1897 my older brothers had left home. We had two pigs we did not need for bacon, and we were short of money; so Dad decided, much against the grain, that we must sell the pigs to the grocer at Shipston-on-Stour. All that we could get for them was 7/6d. per score (20 lbs.) . We had to have them killed and dressed, and I took them in a donkey and cart, all of which we must pay for. Killing the pig One morning before going to work, we got the pig-killer to come and kill the pig, though it would have been more profitable to keep and feed it longer. It was only 160 pounds' weight, which was less than usual for bacon. That morning it had pained Mother to send us to work in the frosty swedes field with only dry bread and a bit of cheese for Dad, and bread and onion for me, besides our bottle of cold tea. Nevertheless, we put our backs under the hayrick for shelter and enjoyed our meal. It was usual to leave newly-killed meat till the next day, but we found that Mother had not been able to resist cooking some for our arrival home that night. Bees and fowls Some might have a hive or two of bees, or a few fowls. It was an amusement to us lads on Sunday mornings, when we could lie in bed a little longer, to listen to the roosters crowing. We could always tell from which roost the different voices came. Some of the old gentlemen were pretty ancient. As soon as one started, just before dawn, others would reply. Then we would say, "Now listen to old Jake's Brahma," or "Cockin1 China" with his gruff voice. Perhaps a little bantam would bring up the rear. Then several would crow together, as though being conducted in their different parts. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 22 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Donkeys Donkeys were the same in the early morning, answering each other from their sheds. They seemed to try to out-do each other with their hee-haws. It was easy to distinguish which was which. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 23 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Recreation Bicycle But a definite change came into my manner of life during my teens. One decision I made. I had bought a bicycle, and when I first took it home into the shed I prayed this prayer: "God help me to use this for Thy service". I hadn't long to wait. A death had taken place in the village on the Sunday, and it was necessary to get a letter thirty miles away as soon as possible. There was no post till the following day, no telephone, no transport. Then my mates said, "You go, you have your bike". So to Shipston post office, four miles away, I went: that meant a great saving of time. medicine. At other times it was to Shipston for the doctor, or a bottle of There were perhaps only six bikes in the village, and all of an inferior sort. Mine was only a boneshaker too, but it did good service. Sports and games Before dark, in late autumn and early winter, the younger men would play quoits on the village green, using heavy metal quoits. In spring, there was football of a sort, after the day's work. They wore their hobnailed boots, so had to watch their shins. The schoolboys would play improvised cricket during their half-hour dinner time; or football, till someone's toe-plate burst the makeshift ball. There was an occasional properlyarranged cricket match between the villages. But with the long days, hay harvest began, and there was little time for anything else till after September, when the harvest was over. As a schoolboy of eight or nine, I was playing outside one of the houses, when the housewife asked me if I had seen her husband go down the road with a load of manure. "No, "I said, "But I sees 'im go down with a load o’ muck. " Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 24 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Education Schoolhouse During winter, the schoolmaster would arrange a welcome concert in the school. The schoolboys would be sent out to all who would lend chairs (we didn't mind that, it was a break from-our lessons), as well as to take them back next day. The schoolmaster got a few magazines, too, for those who could buy them; but reading matter for the long winter evenings was scarce. Some would visit the pub, and spend the few coppers they could ill afford; but there was not much drunkenness. They went as much for company, and to meet others like-minded to themselves. I was allowed there only once, to pay the allotment rent, in a room away from the bar. Books In our home there was a small stack of books on the table. These were hymn books, a prayer book, a Bible, and our prize; from the Church Sunday School. When the Chapel later started a Sunday school, we did, through the kindness of a farmer, get some small book prizes for a year or two. But after he moved to another farm, (as was usual in the tenant-farming community), prizes were too much for the labourer teachers to afford, It was rare to see a silver coin on the plate at a service, the collection amounting to about one shilling and threepence. Afterwards, "The Christian Herald" came into the hands of a few. It was my father's great standby. We read it carefully and gained some knowledge of happenings in the world. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 25 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Religion Methodism I have heard my father say he used to go to chapel with his grandfather; and my mother attended the chapel Sunday school at Brailes. But at the time of my infancy my parents became, to use an old Methodist term, "soundly converted". Dad never went to work before he reached down the Old Book to read a few verses, and then they would pray together. There were two or three other Methodist families whose devotions were of a similar nature. I remember two other mothers with large families coming to visit Mother, who was always concerned for their children, remembering the former character of the village life. They met to pray in a quiet corner of the cottage, away from the children. Later, some of these children, as young men and women, became the pioneers of the Salvation Army in the village. One morning a good Catholic came early to bring a message. Hearing what was going on inside, he waited at the door till it was over before delivering his message. He was well aware of their habits, and agreed with their devotion. I was not so attracted. I liked the chapel and its services. There was the village Bible Class, too, conducted by the Rector's eldest daughter. It included all men, some rather rough and not very refined, but she had a great influence over them. It was she who encouraged me, as well as others, to do a little Christian work, strengthening the influence of my parents. I distributed Christian tracts in some of the village homes on Sunday afternoon (they were eagerly received, as very little reading matter was available), as well as sometimes carrying with me the Wesleyan missionary box. Some of us were attending both Church and Chapel services. I cannot say that I was any better than other mischievous boys of the village, though conscious sometimes that my ways were not what they might be. Marriages There were few marriages, as most marriageable girls were lost to the village, and the young men who were left found their partners at a distance, and were married there. When there was to be a marriage, it was announced in church three Sundays beforehand. Courtships were long, so that they could gather their small Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 26 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. savings. There were few friends at the church to witness the service, though outside some would contrive to have a little rice to greet the couple. Death When there was a death in the family, the body remained in the house till the burial; but neighbours would make room for one and another of the family till after the funeral. It was soon known by the sexton tolling the small bell, and at the end he would toll three distinct tolls for a male, or two for a female. Funerals were attended with much reverence and respect. Someone would offer his services to relieve the family, and would arrange that the bearers be of equal height, for the coffin had sometimes to be carried as far as a mile. A carpenter acted as undertaker, and arranged with the sexton to have two small trestles, so that the bearers could rest or change hands. The procession of mourners was very orderly, the eldest or nearest relatives following first, and then two by two to the youngest or more distant relatives and friends, all carefully dressed in black. This was borrowed if they had none and were too poor to buy, as it was unthinkable not to wear some black clothing as a mark of respect. Sometimes it was only a black crepe band around the arm or the hat. There might be eight or ten couples in procession, besides other friends. Returning in the same order, with the bearers following last, they would be asked to a neighbour's to tea, and would go, out of consideration. Bereavement made all kin. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 27 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Rich and Poor The Squire – Mr Philip Howard, & Foxcote House The Squire was Mr. Philip Howard of Foxcote House. He was a staunch Roman Catholic, and the priest held services at the Hall. On Sundays these were well attended by the village adherents, even though there was a steep hill to climb and some were well on in years. His estate of six good-sized farms were well looked after by the farmers who leased them. What was produced on the farm, except the grain, must be consumed there by the sheep, cattle, dairy cows and pigs, and their manure returned to the land to enrich it. He took a pride in his woods, not allowing them to be overrun, and decided himself which trees should be felled each year, planting others to take their place. Whenever he met the men going home from work, he would take off his hat, and greet them, as if they were lords, instead of labourers on ten shillings a week. At Christmas, the children had a Christmas tree at Foxcote House, with the priest as Father Christmas. The squire would send a wagon for them to the Catholic school in the village, afterwards taking them back home again. My older brother worked for the squire's bailiff on one of the farms. One winter day they were passing the Hall with a light horse and cart. My brother could scarcely walk because of his chilblains, so the bailiff told him, "Get up in the cart, boy". In doing so, he slipped on the frosty iron step and fell, and the wheel went over his leg, breaking it. The squire and his kind lady had "him carried into the Hall. They sent for Dad, working on the estate, and despatched their own man and horse to call the doctor four miles away. Then, in spite of the snow and frost, the squire and his wife walked down to the village to find Mother and convey the news themselves. They asked that she go up to the Hall to nurse her son herself, and live there with the maids, who would attend to them both till my brother was fit to remove home. In two or three weeks, the squire instructed the estate Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 28 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. carpenter to make a stretcher, to prevent any jarring on the stony roads, and had my brother carried home by six men, afterwards sending wood for the cold. Such kindness my parents were very thankful for, and Mother admitted that but for their strong attachment to their Methodist principles, they might have been drawn to the Catholic faith and gone to the Chapel at the Big House. Loaves and fishes sometimes drew adherents to the Church of England or Roman Catholic Church, when there was so much poverty. "Go where you can get the most, " one man said to his wife. But most would not stoop so. The Foxcote estate was all undulating hill country above the village. It was much more interesting to work on the hills than on the flat, low-lying lands north of the village. The country of the North Cotswolds had not much to obscure the vision; there were only the loose stone walls dividing the fields for miles. Here and there were quarries, from which the stone must have been taken years before. cultivation was taking place over them. They were grown over then, and Some places, though stony, grew excellent crops of permanent grasses. That land could easily be worked with two horses, while the low land took four, with a boy. The Manor House One lonely Sunday, I had my father's watch with me for company, and not unpredictably, broke it. So I took it to the Manor House to get it repaired. The old and beautiful building was overgrown and declining, but the working family who lived there were clever and musical. Old Teddy had a big bass viol, and five or six of his sons had other instruments, and they would all turn out to play for dancing. Teddy put the watch to rights for me, and returned it with a stern, "There, don't you do it again". The Rector and his family There was one exception to the usual labourer's wedding: the Rector's daughter. She had the greatest wedding the village had seen. The Rector used only a pony and trap, but there were many carriages in the village that day. The schoolmaster paraded the children as little guards, and all brought flowers to strew the path from the church. There was a flower on the path in front of me with its root attached, so I picked it up to take home to plant. The bridal party was passing; someone said, "Throw that down!" But I put it behind me out of sight. There was much dignity among the church adherents that day. Out of a family of seven, she was the only one married in the village, though they lived there nearly forty years. We were given a holiday and marched to Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 29 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. the great house to view the presents. For the Rector was a very important person, and the Rectory a place of twenty rooms, with gardens, park, and long walks amongst trees and shrubs. The Rector, the Reverend Julian Charles Young, was a truly great man. already been in the living twenty-one years. When I was born, in 1878, he had He had educated the villagers by providing a school for the children, and himself reading to the adults. Later, his voice failed somewhat, though to my knowledge he was quite active the last fifteen years of his ministry at Ilmington, leaving there in 1896. He would attend the school every Monday morning, to give Bible lessons to the top class of twelve and thirteen-year-olds. In 1890, I was happy to receive a large Family Bible, for being the best in religious knowledge. The Rector and Mrs. Young were helpful and generous to the poor families of the village. amongst them were frequent, till age began to tell on both. Their visits When some woman or big girl came out in a different coat or dress, one would hear the remark, "You can see where that came from". Rectory treats For the children, there was always a treat in summertime at the Rectory. The schoolmaster used to march the children from the Church school to the Rectory park. It was a beautiful place. There they would enjoy themselves, till called to sit in a circle for tea, a thing most of them had been looking forward to for days. Some boys would have no dinner, so that they could have a good "tuck in.” It was good fare, such as they were not used to: fresh bread and butter, tea brought round in big jugs to fill their tin mugs, and two sorts of cake. The Rector, with his wife and four daughters, enjoyed the fun of serving, and seeing them eat. It was all done in perfect order: they said Grace as they stood; and at the close, sang a retiring hymn, cheered their thanks, and left with a few nuts each in their mugs. The Rector's eldest daughter arranged a class before the Church service for the young men of the village, and a women's meeting during the week. So devoted was she to this work, that despite some disappointments among the rough and uncouth, she had an influence for good that lasted far on into their lives. A few of her young converts decided to go on to the village green, and try to improve their fellow villagers. The lady was so touched that she went to her classroom secretly, to listen through the open window. This decided her to stand out there with them, and share their witness. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 30 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. At the annual gathering of all those concerned in her work, the Rector listened to the hymn-singing, the speeches and the account of their activities; and then remarked that she was doing more good amongst his parishioners than he was. Miss Young also started a temperance movement for young people. To counter their beer-drinking habits, she hired a room and sold soft drink. Some of this was put into a cask, and fermented, so that it was given to the pigs. The pigs became ill, and the village pig man was sent for. He was puzzled until we remembered the drink: the pigs were drunk. It was soon out all over the village. The Rector and his wife left us by the quietest road they could, not going through the village to be applauded, nor having any public farewell. But I am sure the final "Well done, good and faithful....." will be theirs. “Higher class” A village man going to Chapel once greeted this same housewife as "Ann", but distinguished her companion with "Mrs." This was only because Mrs.---had just come to the village, and he had not learnt her Christian name, whereas he had know Ann all his life. But Ann was displeased that she too had not been called "Mrs. " She lived in a bigger house, and her husband had his own working horse, so she thought herself in a higher class. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 31 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. Transportation -Tom, the one-armed village carrier For yeast, we depended on the one-armed donkey-carrier, Tom. I was sent once a week for "two penn'orth o' barm", which he used to bring in quantities from the Stratford brewery, and sell to the housewives for their bread-making. I was amused to see him measure it out; and if he spilled any down the side, he would wipe it off with his finger and pop it in his mouth, for he could not wash his hand at any moment. Tom had lost his arm in an accident; so his fellow labourers clubbed together to buy him a donkey and cart, and set him up as the village carrier. For years, every Tuesday and Friday, his donkey and cart was a familiar sight on the Stratford-on-Avon road. His wife and one son were dead; but he had another son, small like himself, who helped him with his carrying business. All the cottagers trusted him to the last penny. It was interesting to see him hold his money-bag with his teeth, or between his knees, while he counted out the cash to the housewife for produce he had taken to the Stratford market. If the labourers wanted a new fork or spade, they would say, "Let Tom bring it, " for they could not lose a day's work to get it themselves; and the housewife would ask him to bring a reel of thread. He would have a score of small orders in his cart: eggs; baskets of gooseberries, currants and raspberries; apples; a crate of six fowls; two or three fat ducks; and any other produce from the cottage gardens which people were anxious to make a few shillings on at the market. His little cart was a curious sight when he finally set off. There was often no room for Tom and his son, so they walked at a brisk pace, one on either side of the cart, while the donkey trotted along with her load. When they came to an incline, they would give her a push behind. The eight miles were accomplished in about two hours. Then they would unload; give the donkey a feed and a rest; and deliver and collect their messages. Tom remembered every detail and rarely made a mistake. He had a wonderful memory, for he could not write. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 32 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. The outside world intrudes Imports from the colonies When imports from the Colonies hastened the decline of agriculture, much land went down in grass for meat production. Another difficulty then confronted the farmer; for not only wheat, wool and hides were imported, but meat too began to arrive, with the introduction of refrigerated ships. The Colonies were asking for our manufactured goods, and the Government had to allow their primary produce in, to enable them to pay. Working on the railway After I had left home and was working on the railway, I saw the reason: bacon came from America in twohundredweight boxes. Agricultural depression Employment was not good, so our allotment had to suffice. It provided plenty of food, but no money for groceries, clothing and rent. Dad's quarry had closed down, as by this time stone could be bought already broken. Though he was a skilled farmworker, hedger, mower, rick-builder and thatcher, the farmers pleaded bad prices as the reason for offering no work. Moving to the towns It was then that the young men from the village went to the manufacturing towns, thus relieving the village of its unemployed. If there had been any prospect of better things, some would readily have stayed, to the advantage of the older people. I said that if Dad had only had a donkey, I would have stayed. My mates did not believe I would leave the village till they saw my box in the carrier's cart. I had a complete change of new clothing, carefully made by hand, every stitch, by my mother. With seven and sixpence in my pocket, enough for my fare and a little more, I left my mother at the gate and set out. Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 33 of 34 Re-ordered & edited version of “Our Ilmington”, by John Purser, of Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 1958. POSTSCRIPT Twelve thousand miles and thirty-five years had brought me as far as I could go from the village at the foot of Foxcote Hill. I was living at Upper Hutt, in New Zealand, when, on Christmas Day 1934, the King gave his home and Empire broadcast. Almost unbelievably, the English portion of it was made from Ilmington Manor, now restored to its .ancient beauty by Major and Mrs. Spenser Flower. Straining to hear, I listened with incredulous joy to the voice of the shepherd and the pealing of the bells. Those familiar bells, which I had heard toll two for a woman and three for a man, now filled the whole house with their joyful peal. 3 Bracken Street, Upper Hutt. 1958 Edited by Kevin J. Norman in 2012, from the original property of Ms. Nettie Edwards. Page 34 of 34