F. Scott Fitzgerald (18-19)

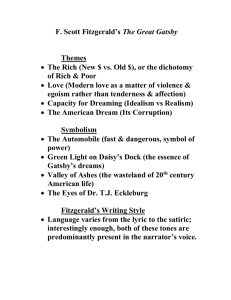

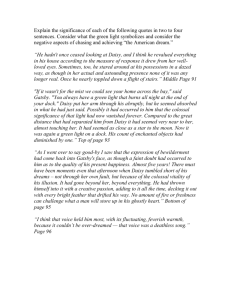

advertisement

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940) Biography Aesthetics Reception Text Beginning of novel Plot Characterization and Narration Gatsby Nick Daisy Tom Jordan Intertexts Horatio Alger Benjamin Franklin Realism Style Biography Scott and Zelda Aesthetics Let me make a general observation— the test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example be able to see things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise. Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are. They are different. Letter to Maxwell Perkins 10 April 1925 The book comes out today and I am overcome with fears and forebodings. Supposing women didn’t like the book because it has no important woman in it, and critics didn’t like if because it dealt with the rich and contained no peasants out of Tess in it and set to work in Idaho? Fitzgerald on Gatsby “The worst fault in it, I think it is a BIG FAULT: I gave no account (and had no feeling about or knowledge of) the emotional relations between Gatsby and Daisy from the time of their reunion to the Catastrophe. However the lack is so astutely concealed by the retrospect of Gatsby’s past and by blankets of excellent prose that no one has noticed it—tho everyone has felt the lack and called it by another name.” Reception Best Sellers of 1925 Soundings, A. Hamilton Gibbs The Constant Nymph, Margaret Kennedy The Keeper of the Bees, Gene Stratton Porter Glorious Apollo, E. Barrington The Green Hat Michael Arlen The Little French Girl, Anne Douglas Sedgewick Arrowsmith, Sinclair Lewis The Perennial Bachelor, Anne Parish The Carolinian, Rafael Sabatini Our Increasing Purpose, A.S.M. Hutchinson F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Latest A Dud —New York World headline Springfield Republican A little slack, a little soft, more than a little artificial. The Great Gatsby falls into the class of negligible novels. Milwaukee Journal The Great Gatsby “is decidedly contemporary: today it is here, tomorrow— well, there will be no tomorrow. It is only as permanent as a newspaper story, and as on the surface.” Gilbert Seldes Fitzgerald has more than matured; he has mastered his talents and gone soaring in a beautiful flight, leaving even further behind all the men of his own generation and most of his elders. Edwin Clark, New York Times Book Review With sensitive insight and keen psychological observation, Fitzgerald discloses in these people a meanness of spirit, carelessness and absence of loyalties. He cannot hate them, for they are dumb in their insensate selfishness, and only to be pitied. The philosopher of the flapper has escaped the mordant, but he has turned grave. A curious book, a mystical, glamourous story of today. It takes a deeper cut at life than hitherto has been enjoyed by Mr. Fitzgerald. He writes well—he always has—for he writes naturally, and his sense of form is becoming perfected. Walter Yust Literary Review The novel is one that refuses to be ignored. I finished it in an evening, and had to. . . . It is not a book which might . . . fall into the category of those doomed to investigation by a vice commission, and yet it is a shocking book—one that reveals incredible grossness, thoughtlessness, polite corruption. H.L. Mencken There are pages so artfully contrived that one can no more imagine improvising them than one can imagine improvising a fugue. Text First Edition In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” He didn’t say any more, but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that. In consequence, I’m inclined to reserve all judgments, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me and also made me the victim of not a few veteran bores. The abnormal mind is quick to detect and attach itself to this quality when it appears in a normal person, and so it came about that in college I was unjustly accused of being a politician, because I was privy to the secret griefs of wild, unknown men. Most of the confidences were unsought— frequently I have feigned sleep, preoccupation, or a hostile levity when I realized by some unmistakable sign that an intimate revelation was quivering on the horizon; for the intimate revelations of young men, or at least the terms in which they express them, are usually plagiaristic and marred by obvious suppressions. Reserving judgments is a matter of infinite hope. I am still a little afraid of missing something if I forget that, as my father snobbishly suggested, and I snobbishly repeat, a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth. And, after boasting this way of my tolerance, I come to the admission that it has a limit. Conduct may be founded on the hard rock or the wet marshes, but after a certain point I don’t care what it’s founded on. When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart. Only Gatsby, the man who gives his name to this book, was exempt from my reaction— Gatsby, who represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn. If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away. This responsiveness had nothing to do with that flabby impressionability which is dignified under the name of the “creative temperament”—it was an extraordinary gift for hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again. No—Gatsby turned out all right at the end; it is what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out my interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men. Plot 1 (intro of narrator; N meets D, Tom, & Jordan; G is mentioned; N sees G looking across the bay) 2 (N meets Myrtle; drunk party in NYC) 3 (party at G; G tells Jordan something amazing; N meets G) 4 (list of people; G’s story, meeting Wolfsheim at lunch with G; Jordan’s G story—allows info to come late in the novel) 5 (G & D meet) 6 (real story of G; Tom suspicious at party; G talks to N) 7 (confrontation in NYC; death of Myrtle; G’s vigil) 8 (G’s version of the romance; N says G the best; break w/ Jordan; George kills G) 9 (N arranges funeral; Mr. Gatz arrives; remeets Jordan & Tom) Delineating Character 1) naming; 2) description of physical appearance, including dress; 3) association with objects, surroundings, possessions, or with images directly introduced by the narrator; 4) direct discussion and analysis of the character by the narrator; 5) actions and behaviour, whether described or represented; 6) talk by the character, including a) talk as action or performance (lying, boasting, betraying, flattering) b) talk as self-defining via vocabulary, dialect, rhetoric c) self-analysis by the character, whether accurate or not. 7) talk about the character by others, accurate or not. Such talk both characterizes the talker and the character talked about. 8) representation or description of the character’s thoughts.* *Adapted from Nina Baym, University of Illinois “I love to see you at my table, Nick. You remind me of a—of a rose, an absolute rose. Doesn’t he?” She turned to Miss Baker for confirmation. “An absolute rose?” This was untrue. I am not even faintly like a rose. She was only extemporizing, but a stirring warmth flowed from her, as if her heart was trying to come out to you concealed in one of those breathless, thrilling words. (19) The telephone rang inside, startlingly, and as Daisy shook her head decisively at Tom the subject of the stables, in fact all subjects, vanished into air. . . . . I couldn’t guess what Daisy and Tom were thinking, but I doubt if even Miss Baker, who seemed to have mastered a certain hardy scepticism, was able utterly to put this fifth guest’s shrill metallic urgency out of mind. To a certain temperament the situation might have seemed intriguing—my own instinct was to telephone immediately for the police. (20) Reading over what I have written so far, I see I have given the impression that the events of three nights several weeks apart were all that absorbed me. On the contrary, they were merely casual events in a crowded summer, and, until much later, they absorbed me infinitely less than my personal affairs. (60) Point of View First person pov: Only one "character" in the story is described as "I." All action is filtered through the thoughts and values of this character, who may be trustworthy—or may not. Second person pov: Rare, but used in contemporary writing. "You" is the primary form of address here, resulting in work which tends to sound very colloquial. Third person pov: Can be omniscient (see inside and report on thoughts of all the characters), limited omniscient (see inside only one mind), or not omniscient at all. "He," "she," are the primary forms of address. There are many continua along which a point of view may be described but the chief are: 1) degree of knowledge of the action; 2) degree of understanding of the action; 3) degree of participation in the action. *Adapted from Nina Baym, University of Illinois He smiled understandingly—much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced—or seemed to face—the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. Precisely at that point it vanished—and I was looking at an elegant young rough-neck, a year or two over thirty, whose elaborate formality of speech just missed being absurd. Some time before he introduced himself I’d got a strong impression that he was picking his words with care. (52-53) “It was a strange coincidence,” I said. “But it wasn’t a coincidence at all.” “Why not?” “Gatsby bought that house so that Daisy would be just across the bay.” Then it had not been merely the stars to which he had aspired on that June night. He came alive to me, delivered suddenly from the womb of his purposeless splendor. (83) “It’s the funniest thing, old sport,” he said hilariously. “I can’t—When I try to—” He had passed visibly through two states and was entering upon a third. After his embarrassment and his unreasoning joy he was consumed with wonder at her presence. He had been full of the idea so long, dreamed it right through to the end, waited with his teeth set, so to speak, at an inconceivable pitch of intensity. Now, in the reaction, he was running down like an overwound clock. (97) “If it wasn’t for the mist we could see your home across the bay,” said Gatsby. “You always have a green light that burns all night at the end of your dock.” Daisy put her arm through his abruptly, but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said. Possibly it had occurred to him that the colossal significance of that light had now vanished forever. Compared to the great distance that had separated him from Daisy it had seemed very near to her, almost touching her. It had seemed as close as a star to the moon. Now it was again a green light on a dock. His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one. (98) As I went over to say good-by I saw that the expression of bewilderment had come back into Gatsby’s face, as though a faint doubt had occurred to him as to the quality of his present happiness. Almost five years! There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams—not through her own fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion. It had gone beyond her, beyond everything. He had thrown himself into it with a creative passion, adding to it all the time, decking it out with every bright feather that drifted his way. No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man will store up in his ghostly heart. (101) No telephone message arrived, but the butler went without his sleep and waited for it until four o’clock—until long after there was any one to give it to if it came. I have an idea that Gatsby himself didn’t believe it would come, and perhaps he no longer cared. If that was true he must have felt that he had lost the old warm world, paid a high price for living too long with a single dream. He must have looked up at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shivered as he found what a grotesque thing a rose is and how raw the sunlight was upon the scarcely created grass. A new world, material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about . . . like that ashen, fantastic figure gliding toward him through the amorphous trees. (169) Daisy looked at Tom frowning, and an indefinable expression, at once definitely unfamiliar and vaguely recognizable, as if I had only heard it described in words, passed over Gatsby’s face. (127) Tom glanced around to see if we mirrored his unbelief. But we were all looking at Gatsby. “It was an opportunity they gave to some of the officers after the Armistice,” he continued. “We could go to any of the universities in England or France.” I wanted to get up and slap him on the back. I had one of those renewals of complete faith in him that I’d experienced before. (136) He wanted nothing less of Daisy than that she should go to Tom and say: “I never loved you.” After she had obliterated four years with that sentence they could decide upon the more practical measures to be taken. One of them was that, after she was free, they were to go back to Louisville and be married from her house—just as if it were five years ago. “And she doesn’t understand,” he said. “She used to be able to understand. We’d sit for hours—” He broke off and began to walk up and down a desolate path of fruit rinds and discarded favors and crushed flowers. “I wouldn’t ask too much of her,” I ventured. “You can’t repeat the past.” “Can’t repeat the past?” he cried incredulously. “Why of course you can!” He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house, just out of reach of his hand. “I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before,” he said, nodding determinedly. “She’ll see.” (116-17) Daisy put her arm through his abruptly, but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said. Possibly it had occurred to him that the colossal significance of that light had now vanished forever. Compared to the great distance that had separated him from Daisy it had seemed very near to her, almost touching her. It had seemed as close as a star to the moon. Now it was again a green light on a dock. His count of enchanted objects had diminished by one. (98) “She’s got an indiscreet voice,” I remarked. “It’s full of—” I hesitated. “Her voice is full of money,” he said suddenly. That was it. I’d never understood before. It was full of money—that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals’ song of it. . . . high in a white palace the king’s daughter, the golden girl. . . . (127) Intertexts “the bold & arduous project of arriving at moral perfection” 1. TEMPERANCE. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation. 2. SILENCE. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation. 3. ORDER. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time. 4. RESOLUTION. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve. 5. FRUGALITY. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing. 6. INDUSTRY. Lose no time; be always employ'd in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions. 7. SINCERITY. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly. 8. JUSTICE. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty. 9. MODERATION. Avoid extreams; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve. 10. CLEANLINESS. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation. 11. TRANQUILLITY. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable. 12. CHASTITY. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dulness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another's peace or reputation. 13. HUMILITY. Imitate Jesus and Socrates. Franklin’s Schedule Realism Epigraph Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her; If you can bounce high, bounce for her too, Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover, I must have you!” —THOMAS PARKE D’INVILLIERS. Titles Gold-hatted Gatsby Trimalchio Trimalchio in West Egg Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires On the Road to West Egg The High-bouncing Lover Gatsby The Great Gatsby Under the Red White and Blue Valley of Ashes The caterwauling horns had reached a crescendo and I turned away and cut across the lawn toward home. I glanced back once. A wafer of a moon was shining over Gatsby’s house, making the night fine as before, and surviving the laughter and the sound of his still glowing garden. A sudden emptiness seemed to flow now from the windows and the great doors, endowing with complete isolation the figure of the host, who stood on the porch, his hand up in a formal gesture of farewell. (60) Style Elements of Style • • • • • • • • • • • sentence length sentence syntax diction parts of speech symbolism dialogue point of view lexicon detail repetitions narrator’s style vs speech patterns of characters "How do you feel, Jake?" Brett asked. "My God! what a meal you've eaten." "I feel fine. Do you want a dessert?" "Lord, no." Brett was smoking. "You like to eat, don't you?" she said. "Yes," I said. "I like to do a lot of things." "What do you like to do?" "Oh," I said, "I like to do a lot of things. Don't you want a dessert?" "You asked me that once," Brett said. "Yes," I said. "So I did. Let's have another bottle of rioja alta." "It's very good." "You haven't drunk much of it," I said. "I have. You haven't seen.” "Let's get two bottles," I said. The bottles came. I poured a little in my glass, then a glass for Brett, then filled my glass. We touched glasses. "Bung-o!" Brett said. I drank my glass and poured out another. Brett put her hand on my arm. "Don't get drunk, Jake," she said. "You don't have to." "How do you know?" "Don't," she said. "You'll be all right." "I'm not getting drunk," I said. "I'm just drinking a little wine. I like to drink wine." "Don't get drunk," she said. "Jake, don't get drunk. "Want to go for a ride?" I said. "Want to ride through the town?" "Right," Brett said. "I haven't seen Madrid. I should see Madrid." "I'll finish this," I said. Down-stairs we came out through the first-floor dining-room to the street. A waiter went for a taxi. It was hot and bright. Up the street was a little square with trees and grass where there were taxis parked. A taxi came up the street, the waiter hanging out at the side. I tipped him and told the driver where to drive, and got in beside Brett. The driver started up the street. I settled back. Brett moved close to me. We sat close against each other. I put my arm around her and she rested against me comfortably. It was very hot and bright, and the houses looked sharply white. We turned out onto the Gran Via. "Oh, Jake," Brett said, "we could have had such a damned good time together." Ahead was a mounted policeman in khaki directing traffic. He raised his baton. The car slowed suddenly pressing Brett against me. "Yes," I said. "Isn't it pretty to think so?" (246-47) The chauffeur came out, folding up the papers and putting them in the inside pocket of his coat. We all got in the car and it started up the white dusty road into Spain. For a while the country was much as it had been; then, climbing all the time, we crossed the top of a Col, the road winding back and forth on itself, and then it was really Spain. There were long brown mountains and a few pines and far-off forests of beech-trees on some of the mountainsides. The road went along the summit of the Col and then dropped down, and the driver had to honk, and slow up, and turn out to avoid running into two donkeys that were sleeping in the road. We came down out of the mountains and through an oak forest, and there were white cattle grazing in the forest. Down below there were grassy plains and clear streams, and then we crossed a stream and went through a gloomy little village, and started to climb again. We climbed up and up and crossed another high Col and turned along it, and the road ran down to the right, and we saw a whole new range of mountains off to the south, all brown and baked-looking and furrowed in strange shapes. (93)