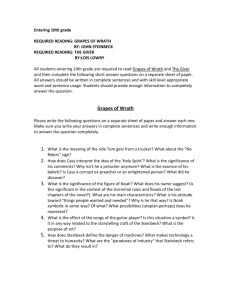

The Grapes of Wrath - Wayzata Public Schools

advertisement

“The Grapes of Wrath” Discussion notes The Grapes of Wrath: Exam 2 preview Identify instances where we see the shift from “I” to “We.” Recognize how this connects to Transcendentalism. Particularly re-visit – Chapter 17: Review the “society” that sets up nightly on the road: the rules, the customs, punishments, etc. – Chapter 18: The conversation between Sairy Wilson and Casy before the families separate. Would you generally know about: Mae, the waitress at the diner (chapter 15) and what happens there? The one-eyed man at the junkyard, how Tom reacts to him, and Tom and Al’s purpose for going there (chapter 16)? The declining number of Joads? Discussion notes: Chapters 19-21 “We ain’t foreign.”: – Some critics charged Steinbeck was racist in the implication that the migrant farmers were somehow better than the Filipinos or Mexicans that had traditionally made up California’s agricultural workforce, simply because the farmers were white Americans. – However, the broader issue went beyond race and to the changing social landscape: Now it wasn’t just foreigners who were being oppressed. Discussion notes: Chapters 19-21 Anger – Landowners hate the Okies. The storeowners hate the Okies. The native California workers hate the Okies: “These goddamn Okies are dirty and ignorant.” – The Okies are getting angry: “A fallow field is a sin, and the unused land a crime against thin children.” – In a land of plenty, they are starving. Discussion notes: Chapters 19-21 1. 2. 3. Steinbeck says the landowners ignored the three cries of history: When property accumulates in too few hands, it is taken away from the many. When a majority of people are hungry and cold, they will take by force what they need. Repression works only to strengthen and knit the repressed. Discussion notes: Chapters 19-21 What Casy finally learns in jail after giving himself up to save Tom and Floyd is that man’s spiritual brotherhood must express itself in social unity. He becomes a labor organizer. Discussion notes: Chapters 22-26 Chapter 25 details the deliberate destruction of the harvests in order to keep prices up, while children are starving to death. Steinbeck refers to this as a “crime that goes beyond denunciation” and “a sorrow that weeping cannot symbolize.” “In the eyes of the people there is the failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy for the vintage.” Discussion notes: Chapters 22-26 “Well, they was nice fellas, ya see. What made em’ bad was they needed stuff. An’ I begin to see, then. It’s need that makes all the trouble. I ain’t got it worked out.” Luke 23:34: “Father, forgive them. For they know not what they do.” Casy’s last words: “You fellas don’t know what you’re a-doin. You’re helpin’ to starve kids.” Discussion notes: Chapters 22-26 Steinbeck’s depiction of extreme poverty is not without relevancy today. In his time, homelessness and despair existed within the larger context of the Depression, and the general public was, for a while at least, genuinely touched and angered by the suffering of migrants. Discussion notes: Chapters 22-26 Today, some argue that prosperous Americans seem all too willing to accept the presence of homeless people on the streets and a desperate “underclass” in the ghettos. Discussion notes: Chapters 22-26 Think back to “Roger and Me”: The pursuit of money is a perfectly legitimate activity in our society: It is the basis of capitalism. But what happens when, in the quest for the dollar, human values are forgotten? – In the context of the novel, banks force people from their homes; big farmers eat up little farmers; landowners exploit workers. At what point does the pursuit of money turn into a crime? Discussion notes: Chapters 27-30 By the time we reach the end of the book, the transformation from the single family to the human family is complete: – The Joads and Wainwrights live in the same box car. – When Al tears down the tarp that hangs in the middle of the boxcar, “the families in the car were one.” – Al and Aggie decide to get married, completing the literal and symbolic merger of the two families. Discussion notes: Chapters 27-30 Transformations – Emerson’s “Oversoul” has the consequence of living by the truth that humankind is bound to one another with spiritual bonds. We become responsible for what happens to our neighbor and to society in general. – This principle is exemplified in Ma, Rose of Sharon, the Wilsons, and the Wainwrights. – But nowhere is this manifested more than in Jim Casy and Tom Joad. Discussion notes: Chapters 27-30 The transformation of Jim Casy “Maybe it ain’t a sin. Maybe it’s just the way folks is … There ain’t no sin, and there ain’t no virtue.” “What’s this call, this sperit? An I says, ‘It’s love. I love people so much I’m fit to bust, sometimes.’ “Maybe it’s all men an’ all women we love; maybe that’s the Holy Sperit – the human sperit – the whole shebang. Maybe all men got one big soul ever’body’s a part of.” “I ain’t sayin I’m like Jesus. But I got tired like Him, an’ I got mixed up like Him, an’ I went into the wilderness like Him . . . There was the hills, an’ there was me, and we wasn’t separate no more. We was one thing. An’ that one thing was holy.” “An’ I got thinkin … how we was holy when we was one thing, an’ mankin’ was holy when it was one thing. An’ it on’y got unholy when one mis’able little fella got the bit in his teeth an’ run off his own way, kickin’ and draggin’ an’ fightin.’” Discussion notes: Chapters 27-30 All of Casy’s teachings crystallize in his disciple: Tom – In prison, Tom learned to mind his own business and to live one day at a time. By the end of the book, he prepares to leave his family to continue what “Casy done”: He dedicates himself to work for the improvement of his people, though it may mean imprisonment or his own death. Discussion notes: Chapters 27-30 “Well, maybe like Casy says, a fella ain’t got a soul of his own, but on’y a piece of a big one – an’ then – then it don’t matter. Then I’ll be aroun’ in the dark. I’ll be ever’where – wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. If Casy knowed, why, I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an – I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build – why, I’ll be there. See?” (419) That controversial ending What it reveals: Those who do not share, who continue to be selfish and distrustful, “worked at their own doom and did not know it.” That’s what makes Rose of Sharon’s feeding of the old man with her own breast milk that much more powerful: Saving a life is the most intimate expression of human kinship. That controversial ending The religious overtones are apparent: the still, mysterious, and lingering quality of the final scene, as “her lips came together and smiled mysteriously” (the last words of the novel), might suggest the subject of numerous religious paintings: the Madonna nursing her child, whom she knows to be the Son of God. It could be interpreted that Rose of Sharon’s child was sacrificed to send a larger message to the world. This is supported by Uncle John sending the dead baby down the river: “Go down an’ tell ‘em.” That controversial ending What’s more, the name Rose of Sharon comes from the Song of Solomon: “I am the Rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys.” This name is often frequently interpreted as referring to Jesus Christ. Thus, this final scene could be seen as symbolic of the Eucharist: “Take, eat, this is my body…” Rose of Sharon gains the wisdom that she is doing an ultimate act for humanity: She is sustaining life. That controversial ending The bigger picture is this: The ultimate nourishment is the sharing of oneself and whatever one has to help others: Rose of Sharon symbolizes this by giving the only thing she has to give: literally, her physical self. Test #3: Preview 30 multiple choice questions that cover chapters 1930; 8 short-answer questions totaling 10 points; one essay (10 points). Five of the multiple choice questions over the supplementary readings (including comparisons between economic conditions now and those during the Depression). Closely review chapters 23 and 25 Essay: – Be prepared to thoroughly discuss your interpretation of the over-arching message of the book, especially the ending : How should we view the Joads’ situation and transformation at the end of the book? There is no right or wrong, but there is “better-informed” vs. “scratched-the-surface.”