File - Political Science Department, St.Philomenas

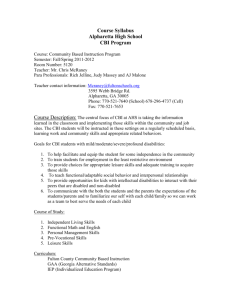

advertisement

TEACHING POLITICS

i

TEACHING POLITICS

In this Issue ARTICLES

G. Haragopal and V. Sivalinga Prasad

Administrative Concepts: The Question of Values

B. Venkateswarlu

Theories of Organisation and Development

John Forester

A Critical Empirical Framework for the Analysis of Public Policy

Satya Deva

Administration in Developing Societies

G. Ram Reddy and G. Haragopal

Bureaucracy and Development: Case Study of Rural India

A.S. Narang

Administration, Politics and Society: Indian Case Study

O.P. Sharma

Public Accountability and Administration: Anti-Corruption Strategies in India

BOOK REVIEWS

Guest editor: Prof. G. Haragopal

This Special Issue is also available in book form.

Contact:

AJANTA BOOKS INTERNATIONAL 1UB,

Jawahar Nagar, Bangalow Road, New Delhi

Price:

Paperback : Rs. 40.00

Hard Bound : Rs. 80.00

ii

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Prof. G. Ram Reddy, Vice-Chancellor, A.P. Open University Hyderabad.

Prof. G. Haragopal, Centre for Economic and Social Studies Hyderabad.

Dr. B. Venkateswarlu, Dept. of Political Science, University Evening College, Warangal.

Dr. Satya Deva, Department of Public Administration, Punjab University, Chandigarh.

Dr. V. Sivalinga Prasad. A.P. Open University, Hyderabad.

Prof. John Forester teaches Political Science at Rutgers Uni., Newark, New Jersey (U.S.A.)

Dr. Amarjit S. Narang, teaches politics at Shyam Lal College, Delhi University, Delhi.

Dr. OP. Sharma, Vice-Principal, Bhagat Singh (Evening) College, Delhi University, Delhi.

1

1ADMINISTRATIVE CONCEPTS: THE QUESTION OF VALUES

G. Haragopal and V. Sivalinga Prasad

Values, which form the basis for human behaviour, constitute an important dimension of social

phenomenon. The study of values of individuals, groups, cultures

and societies can provide a clue to the understanding of the socio, political and economic

transformation. How values are shaped and altered is a cardinal

aspect of any discussion on development or change in any society. While the values of the individual are

largely shaped by the general socio-economic set-up,

the values of the socio-economic set-up are determined by the level and type of productive processes.

The striking variation in the value framework of

different groups in the society is primarily due to the differences in the economic interests of these

groups. The variations in the value set-up of individuals

within the group is on account of socialisation process which includes exposure, schooling, association

with others and contemporary social events etc.

The heterogeneous character of value framework indicates the wide ranging conflict of interests in the

society. It is such factors that account for the

complexity in behaviour which poses problems, if not challenges, to the correct understanding and

analysis of the social behaviour and its value premises.

2

As values get crystallised in a society, they transform themselves into structured institutions through

which they get articulated. In the social pyramid

these institutions range from the family at the base to the state at the top. The grip of the values can be

perceived from the relative stability of these

institutions. Therefore, the study of institutions and their value framework is one important method to

understand the larger social phenomenon. In this

context study of political and administrative institutions assume considerable importance to a serious

student of developmental process. In most of the

developing countries, where the political institutions are not well developed, the administrative

structures have come to play a dominating role. Hence

the study of administration is of critical importance in these countries.

A study of administrative institutions in the past has been undertaken particularly from the point of their

configuration, internal processes and other

managerial aspects. The studies which throw light on the value framework of the institution are scanty.

This may be partly due to the influence of thinkers

like Max Weber who assumed that these instruments can be value-neutral. This raises a fundamental

question whether any institution or an instrument can

be value-neutral at all. The notions of value-bound, value-neutral and value-free institutions exist due to

seeming (apparent) variations in the social,

economic and cultural set-up. While the value-boundedness is sharply reflected in a heterogeneous

society, they get concealed in societies whose value

premises are deep and well entrenched. In Riggsian parlance it is in prismatic societies where valuecomplexity tends to be high. Transformation of a 'prismatic

society' into a 'refracted society' gradually gives rise to a socio-economic framework where the value

premises of the society tend to acquire relative

stability. The process of transition calls for change in the concepts and practices which can be noticed in

the evolution of administrative theory. The

classical concepts of organisation laid emphasis on structured human relations for the purposes of

economy and efficiency, which in turn would step up

the quality and quantity in the productive processes. In the decision-making concept, attainment of the

goals has

3

come to occupy utmost importance. Simon separated values from ethics. For, his theory of rationality

emphasises on selecting appropriate means to achieve

the ends rather than the broader ethical questions involved both in the choice of the ends and in

selection of the means to achieve those ends. Most of

the administrative concepts like Scientific Management (Taylor), Theory of Authority (Chester Barnard),

Human Relations Movement (Elton Mayo), originated

in response to the qualitative changes that were taking place in the larger system. This is significant in

the context of transformation of feudal structures

into capitalist organisations in the West and particularly in the United States.

The concept of scientific management seeks to economise human energy for its efficient and effective

utilisation. Dissipation of human energy was a part

of the feudal structures which were opposed to the release of the productive forces. The release of

productive forces compel the removal of constraints.

It is this attempt that gave rise to the concept of scientific management. On the human relations front,

the worker needed to be better managed for greater

productivity. As a result, the feudal authoritarian structures had to give way to engineering of human

relations. Barnard cautioned the managers that authority

lies in the person who is accepting it than in the person who is exercising it. It is this logic that led to the

reorientation of human relations. The

Hawthorne experiments were mainly intended to understand the human psychology so that the

knowledge it produced could be geared for greater productivity.

Thus human engineering to step up productivity was the main premise of the new experiments and the

concepts.

This only indicates that the debate on the question of values is closely related to the phase of social

transformation and level of economic development.

It is this historical process that raises two basic questions; one, are the countries where these concepts

are being taught passing through the same type

of transition and two, can the present level of development in the third world countries be compared to

the level and type of development obtained in the

western countries when these concepts were evolved. It is these

4

pertinent questions that are discussed in this section.

II

An examination of the syllabi of different universities particularly the papers on administrative theory,

development and comparative public administration

and management science, reveals that there is a common pattern. The paper on administrative theory

in the Indian universities includes the concepts of

Woodrow Wilson, Luther Gullic, Urwick, Mary Follet, Henri Fayol, F.W. Taylor, Max Weber, Elton Mayo,

Chester Barnard, Herbert Simon, F.W. Riggs, Douglas

McGreger, Herzberg, George Homans, Rensis Likert Warren Bennis, Abraham Maslow, Chris Argyris,

Yezhkhel Dror, Mosca, Michels, Colebiwski, Robert Dahl,

Raven, Etzioni, Kingsley, Kelshell, Van Riper, Subramanyam etc. In a couple of universities Marx also

figures in.

The paper on management science includes scientific management, administrative planning, division of

work, coordination, management by objectives, management

by exception, work study, work measurement, work simplification, net-work analysis, systems analysis,

management information systems, inventory control,

O&M, C P M and PERT, PPBS, operations research, cost-benefit analysis etc. These techniques and

concepts are the continuation of the classical approach

which emphasised efficiency, economy and rationality as basic premises of the organisation

phenomenon.

The list of thinkers and concepts indicates the over-riding bomination of the thinkers from West and

more so of the U.S.A. The concepts they developed have

had their origins in the western experience and their needs and demands. The United States of America,

where the productive forces have been triggered

through capitalist mode of development, witnessed major technological break-throughs in the area of

production and experienced major changes in the area

of human relations in organisations. The 'administrative theory' is the response or the result of

developments and changes in organised human relations.

It is these concepts that were imported, if not transplanted, into most of the third world countries. But

to the dismay of many of the western thinkers,

5

the concepts and the practices stemming from these concepts made no impact on the administrative

process. It is this experience that called for a different

conceptual framework to explain the organisation phenomenon.

The rise of Afro-Asian nations in the forties and fifties gave rise to new trends of thinking in the field of

organisational theory. It was found that the

experience gained by the U.S.A. and the west was not relevant to most of the third world countries. For

their economies have been backward in content and

feudal in structure. The transition of a feudal society into a capitalist culture may render the

organisational theory to some extent relevant, but most

of the third world countries are stuck up in crisis of change. The constraints for capitalist development

tend to be both internal and international. Therefore,

the scope for the rise of capitalism in most of the third world countries is quite restricted. Added to it,

most of the governments of these countries

explicitly stated in their policies and programmes that they are 'committed' to 'socialistic pattern of

society'. It is these conditions and postures that

limit the usefulness of the concepts developed in the west. The western thinkers themselves conceded

this point and pleaded for new theoretical paradigms

to explain the organisational phenomenon in the third world countries. It is this recognition that led to

the genesis of comparative public administrative

and development administration approaches. These two trends do find a place in the teaching of

administrative theories in India.

An examination of the syllabi of comparative public administration of different universities indicates that

the countries which are recommended for the

purpose of comparative analysis are; U.S.A., U.K., France and U.S.S.R. The concepts generally discussed

in this paper are; the Weberian ideal type, the

general systems approach, efficiency and rationality model, Riggsian concepts of agraria and industria,

characteristics of colonial administration, administrative

modernisation etc. These concepts compare the developing countries with that of the western models.

The common theme in these papers is to explain the

variations in different administrative patterns. They also attempt to explain the

6

variation and point out that variation as the cause for the inefficiency and ineffectiveness of the

organisations in the third world countries; they indirectly

suggest that western models would help in overcoming the growth crisis. Thus the comparative public

administration approach reinforced the western values

and premises as a frame of reference for our understanding the administrative phenomenon.

The paper on development administration which is an offshoot of comparative approach focuses its

attention on the transition or change in the third world

countries. Under this paper the ideas of Hahn Been Lee, Riggs, Milton Esman, Swerdlo, Pai Panandiker

find a place. In addition the concepts of administrative

modernisation, innovations in developing countries, institution building, citizen participation, problems

of bureaucracies etc., are included. The syllabus

of development administration in content is not quite different from comparative public administration

as it also includes several concepts and paradigms

of comparative public administration. In some of the universities these two papers are clubbed into one

paper.

In an attempt to explain the variations on the one hand and transition on the other, the teaching of

'administrative theory' is dominated by the western

capitalist values either as a frame of reference or as a tool to explain the variations in the organisational

phenomenon. The major limitation of such

an approach lies in its failure to explain the general ambiguity and growing complexity in the value

frame of the organisations in most of the third world

countries. The large scale inefficiency, rigid heirarchical structures, authoritarianism, suspicion, absence

of team-work, breakdown of coordination, centralisation

of decision-making are some of the typical characteristics of the bureaucracies in the third world

countries in general and in India in particular. The

concepts that are taught in the class rooms are not capable of explaining as to why the administrative

system behaves the way it does. This indicates that

the value premises on which our bureaucracies operate are entirely different.

7

This debate gives rise to one basic question, viz., what are the value premises of third world

bureaucracies and where

from they imbibe these values. Riggsian analysis does provide a clue to understand the relevance of

social values to the larger socio-economic system. And

this leads us to a point where we have to ask another question whether the administrative concepts in

their present form are capable of explaining the

causal relations that are at work in the administrative phenomenon. Even in a country like France,

Michel Crozier in his analysis on bureaucratic phenomenon

found that there has been a shift in the value framework of the French society which is not adequately

reflected in the French bureaucracy. Hence he finds

the bureaucracy in France not being able to cope with the needs and demands of the society. It is such

factors that limit the utility of western theories

in explaining the organisational or development phenomenon in developing countries like India.

That the third world countries are passing through a rapid transition is now universally accepted. It is

this transition that renders understanding of the

social phenomenon difficult. This complexity arises on account of the fact that these societies continue

to be under the grip-of feudal value framework

but have adopted capitalist strategies for developmental purposes. Added to it they swear by socialist

goals. It is this three dimensional phenomenon with

its inherent contradictions that cause the complexity. The attempt to reconcile these contradictory

values make the task of understanding the organisational

phenomenon difficult. Therefore, the administrative concepts built on western value framework prove

to be inadequate in explaining and analysing the administrative

phenomenon.

III

That the administrative systems cannot be separated from their larger socio-economic systems needs no

emphasis. If this premise is accepted, then the limitations

of administrative concepts are too obvious to need any explanation. If the purpose of theory is to

explain the causal relations, the existing 'administrative

theory' is stuck with superficial causes in explaining the serious efforts that are experienced in the

organisations. As a result administrative theory

incorporated

8

by and large in our syllabi becomes ineffective in explaining the administrative phenomenon. In order to

be more effective the explanation has to go beyond

the administrative system and find the causes in the larger system.

In the study of administration, its inter-relations with the larger system assumes considerable

importance. The study of administration is basically a study

of change and its impact on organisations. Therefore, the focus of administrative concepts will have to

be shifted to the larger issues and broader value

framework. This focus would render the concepts and the thinkers who discussed and analysed social

transformation relevant to the administrative theory.

While western concepts could explain the transition that those societies passed through, the framework

must be broadened so as to include the global experience.

This would enable one to appreciate critically the organisation phenomenon—its strength and

limitations.

The western theories have been emphasising increasing role to the state and its widespread

instruments. They also assume that this intervention is positive.

In contrast, third world thinkers like Gandhi were suspicious of the state and pleaded for the village

swarajya based on the concept of total decentralisation

of power. The scheme that Gandhi suggested included increasing control by the lower level

organisations over the higher levels. In addition his concept

of people's participation through non-cooperation, civil disobedience and satyagraha added a new

dimension to the process of change and the tasks that

the administrative system should face.

Development thinkers like Paulo Friere from Latin America or Frantz Fanon from America discussed in

their works the basic trends in the change process.

The discussion on colonialism and its influences on the one hand and the increasing concientization or

politicisation of the masses on the other does provide

an insight into the challenges and the crisis that administrative systems are facing. The works of these

two thinkers explain the profound changes that

the developing societies are passing through. This comprehensive understanding would give one the

capacity to relate the administrative sub-system to the

larger socio-economic

9

system.

The theories of social change through resolution of contradictions as developed by Marx, Lenin and Mao

should find their due place in the courses on administrative

concepts. For the class struggle, the role of the state and the consequent process of change provide a

wider perspective. The role and nature of administration

cannot be entirely different from those of the state. In a class society, can the administrative system be

above the class interests? Can it cast its support

in favour of the poor against the will of the privileged class? Can the state play a positive role in such a

situation is a fundamental question that a

student of administration requires to appreciate. This understanding provides an alternative angle to

look at the complex value system of the organisation

phenomenon.

References

1. Barnard, Chester, "The Functions of Executive, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1940.

2. Esman, Milton J., "The Politics of Development Administration", in John D. Montgomery and William J.

Siffins (ed.), Approaches to Politics, Administration

and Change, McGraw Hill, New York, 1966.

3. Fanon, Frantz, Wretched of the Earth, Grove, New York, 1965.

4. Friere Paulo, Cultural Action for Freedom, Penguin, London, 1977.

5. Gandhi, "Village Swarajya", Navajeevan, Ahmedabad, 1962.

6. Gulick, Luther and Urwick, Papers on Science of Administration, Institute of Public Administration,

New York, 1937.

7. Lenin, V.I., Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Collected Works, Moscow, 1972.

8. Mao Tse-tung, Collected Works, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1965.

9. Marx, Karl, Collected Works, International Publishers, New York, 1975.

10. Mooney, James D., The Principles of Organisation, Harper and Brother, New York, 1939.

10

11. Nicholas, Henry, Public Administration and Public Affairs, Prentice-Hall, Inc. Engle Wood Cliffs, New

Jersey, 1975.

12. Palombara, Joseph La, "An Overview of Bureaucracy and Political Development", in Joseph La

Palombara (ed.). Bureaucracy and Political Development, Princeton,

1963.

13. Riggs, Fred W., "An Ecological Approach: The Sala Model", in Ferrel Heady and Sybil C. Stokes, (ed.),

Papers on Comparative Public Administration, University

of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1962.

14. Simon, Herbert A., Administrative Behaviour, Macmillan Co., New York, 1945.

15. Waldo, D., "Scope of the Theory of Public Administration", in James C. Charles Worth (ed.), Theory

and Practice of Public Administration, Scope, Objectives

and Methods. The American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, Philadelphia, 1968.

16. Wilson, Woodrow, "The Study of Public Administration", Political Science Quarterly, 2 June, 1887.

11

2 THEORIES OF ORGANISATION AND DEVELOPMENT

B. Venkateswarlu

There has been a growing discontent among the students of administrative theory especially in the Third

World countries like India about the inadequacies

of the western theory of administration as an explanation to the social reality and its criticism.1 They

have begun to realise that these theories, originated

as they are in the west, may provide something of a conceptual framework for analysis of distribution of

power but cannot serve as a substitute for such

analysis. Because, they came to know, of late, that these theories leave many questions pertaining to

social reality unanswered. They have been even expressing

doubts whether there can be a realistic theory of administration at all.2

This being the case with the Third World intellectuals, the thinking in the west, it appears, is in no way

different. The western liberal theorists have

characterised the organisation theory with such phrases as "elephantine" and "jungle".3

In the face of this persisting confusion in the countries of its origin and development, the theory had

interestingly gained prominence among the administrators,

academics and the leaders of the communist parties in Soviet Union and its allies i.e., East European

countries.4 These countries were accused of increasing

bureaucratisation of their societies,5 thus raising serious doubts about the credibility of the

12

socialist system.

Be that as it may, Marxist intellectuals have recently shown concern about administrative theory.6

While this concern has been to analyse and understand

the structure and functioning of the capitalist state, there has been a growing tendency among them to

attempt to arrive at new theories such as "Marxist

theory of administration",7 and "Leninist theory of organisation"8, which involve the risk of vitiating the

use made of the concepts of Marxism.9 Instead

of clarifying the existing confusion, this has actually added to the existing one. What is more, this

tendency has been treated as "yet another jungle".

With a view to understand the nature of the existing confusion in the field of administrative theory, this

article makes an attempt to note the sociological

origins of the theory and its nature. This in itself might contain a clarification to the problem whether

the theory of administration is a universalistic,

realistic and scientific theory that can be useful as an explanation to the social reality. It also examines

briefly the Marxists' concern for the theory

and its repercussions in the pursuit of scientific knowledge about the social reality.

II

The emergence of the theory of administration as a distinct intellectual discipline in pursuing knowledge

about social reality has been a recent phenomenon.

The post-war period has been marked by proliferation of a number of institutions both private and

public, both in the Third World countries and the capitalist

west, for the purpose of teaching, research and consultancy in management, organisation and

administration. Simultaneously the establishment of separate

departments of administrative sciences as estranged from the traditional disciplines such as Political

Science and Economics in the universities was on

the increase. Though the origin of the modern management and organisational techniques can be

traced back to the latter half of the 19th century i.e.,

in the initial stages of the formation of monopolies in the west, the reasons for their increased

importance

13

can be found in the post-second world war developments which forced the monopoly corporate

business to reorganise and reorient their strategies for the

purpose of readjusting themselves to the changed situation.

The process of decolonisation had put a full-stop to the ruthless and naked exploitation of the colonial

type; and the newly emerged nations had begun to

plan national reconstruction of their economies as independent nations. While the former appeared to

have been a potential threat to the capitalist west

for exploiting enormous raw materials and cheap labour, the latter had threatened them of their vast

markets in these countries.

Further, in the first half of this century, the emergence of Soviet Union after the October Revolution as

an entirely different system of society opposed

to capitalism and imperialism, with its proclaimed ideological commitments of solidarity towards the

rising working class movements and social revolutions

in various countries, had posed a major threat to western capitalism and its global interests as a whole.

The War and its aftermath had witnessed the emergence of U.S.A. and the Soviet Union as two major

powers with two different ideologies, and this had resulted

in the bi-polar division of the world into Capitalist camp and Socialist camp. The war was followed by a

short period of cold war between the two camps.

It was a war waged actually between two different ideologies, fought by means of vigorous ideological

propaganda to attract the decolonized nations.

The unfolding reality confirmed Lenin's thesis that with capitalism reaching the highest stage of its

development, viz. monopoly capitalism or imperialism,

what is exported is not capital goods but capital itself. It meant a marriage between the monopoly

capital and the 'indigenous capital' of the newly emerged

nations, the purpose of which had been the pumping out of enormous profits from these nations to the

developed west.

It would not ordinarily be possible for imperialism to accomplish this task. But as there was no

contradiction between monopoly capital and the so-called

indigenous capital whose interests boiled down to one task viz. making huge profits, it

14

became easier for imperialism to accomplish this task. And capitalism met this task by the process of

reorienting the world outlook of the populations in

the newly emerged, underdeveloped nations. This mental reorientation was total in the sense that it

made an all out attempt to condition the thinking of

the entire populace of a given country, socially, politically, economically, culturally, ethically,

educationally and religiously. It had to mould, against

all odds, the total outlook of the population to believe in the virtues of capitalism, in the face of

degradation of human life under ruthless, albeit

indirect, exploitation of the masses. Without such exploitation capitalism could not dream of its survival.

Thus, capitalism in the epoch of imperialism does not only export capital but also capitalist ideology.

And the tasks of this ideology are not merely to

prepare the people to believe in the 'rational' virtues of capitalist development which acquire distinct

nomenclature such as industrialisation, modernisation

etc., but to condition them both mentally and physically to serve capitalism. As part of its overall

strategy, capitalism in the epoch of imperialism exports

ideas. There is a proliferation of educational institutions for the purpose of imparting skills, techniques

of management, organisation and administration

of the societies in the underdeveloped countries, that serve the requirements of imperialism. The

already existing institutions are injected into the system.

Various trusts and foundations like Ford and Rockefeller give scholarships to the intellectuals of these

countries to go to the west to be trained both

directly in their numerous business schools and universities, and indirectly, be attracted to their lifestyles. After their return, these intellectuals

occupy the key positions in the prestigious institution of management and organisation and also in the

administration of these societies.

This being the reason for the origin and existence of the theory of administration or organisation in

these countries which had come to serve the interests

of capitalism and the resultant capitalist class-rule, the students, atleast the conscientious ones of

administrative theory feel rather naively that the

theory can really serve the purpose of the society as a whole. When it cannot do so, they are

disillusioned. And

15

this disillusionment has led them to search for new theories of administration. As a result has emerged

"Marxist theories of administration or organization".

The aims and objectives of the theory and practice of administration, organisation or management, as it

is distinctly called, are not however, intended

for the development of the society as a whole either in the countries of its origin or in the countries

which imported it. Contrarily its aims are, firstly,

to keep the less developed countries persistently underdeveloped which has been the historical

necessity of capitalism in the epoch of imperialism, and

secondly, to protect a small minority of capitalists of their immense wealth and their rights in the

ownership of the means of production as their private

property. In other words, the theory and practice of administration is in reality nothing but the theory

and practice of exploitation and oppression by

a small minority over a big majority, i.e., the capitalist class-rule.

III

Though there are a number of thinkers who have contributed to the theme, for the purpose of a brief

analysis, one could choose from the writings of a few.

They are Fredrick Winslow Taylor, Max Weber, Elton Mayo, Chester Barnard, Herbert Simon and Fred W.

Riggs. The ideas of the first two are considered as

"classical"; the next three were named as belonging to "human relations school". Simon and Riggs fall

under "Decision-making" and "Development" Schools

respectively.

The history of capitalist development11 has been divided into three phases namely, (1) mercantile

capitalism, (2) competitive capitalism, and (3) monopoly

capitalism or imperialism.18 According to Marx, mercantile capitalism was "a system of robbery . . .

directly connected with plundering, piracy, kidnapping

slaves and colonial conquest".13 It was the age of merchant-adventurers who formed themselves into

small joint trades. Thus they were the founders of the

modern system of joint stock companies. Accumulation of wealth through their expeditions had been an

encouragement for them to become small entrepreneurs

who began to produce a limited number of commodities in

16

common circulation. These commodities included the basic food stuffs in more or less unprocessed form

such as grains, meat, fish and meals, dairy products,

vegetables, liquors, bread and biscuits and molasses, tobacco, coal and candles, lamp oils and soaps,

tallow bees wax and paper. Actually, these and many

more other household needs were actually produced by the households in the country-side at their

homes to meet their daily requirements.14 In this period,

the role of the family remained central in the production processes of the society. This process of

production was simple and homogeneous. By 1850 the

capital's capture of this simple process of production of household needs in the country-side was

complete. This gave rise to growth of urban centres where

all these goods were produced by the machinery under factory system, resulting in the bulk production,

available at cheap prices. This hit the harmonious

life of the country-side by uprooting the agrarian population from their stead only to be absorbed as

wage labourers by the factories at the fast growing

urban centres; with this, it did not take much time for the capitalist entrepreneurs to compete with each

other for producing more to amass more wealth.

Production of more commodities resulted in further cheapening of goods, and thus the labour-power.

Those who are familiar with rudimentary laws of capitalist

development know that this process (known as "falling rate of profit") ultimately goes against the actual

producers i.e., workers. With this capitalism

enters the competitive stage.

At the risk of over-simplification Baran and Sweezy described this stage as follows: "The competitive

firm was small relative to the size of the industry

of which it was a member. It brought factors of production (labour, raw material and machinery) and

sold standardized product at prices over which it had

no control. In these circumstances, it could strive for maximum profits only by improving its techniques

and/or organization—in other words, by actions

which were necessarily confined to its own production process. Maximum profits and optimum methods

of production thus went together resulting in the more

and better products at lower cost".15

17

It is at this stage as Godelier had pointed out, that the capitalist does transform one faction of his capital

into labour power and tries to get the best

results from this. This means, influencing the factors of production. Analysis of these factors is the

concern of what is called "scientific labour management"

or "rational organization of labour". At the beginning of this century F.W. Taylor studied this

rationalization of labour with a view to eliminating all

waste of time in the workers' movements and determining the movements and speed of motion best

adapted to the machine. This meant, in short, a predominantly

psychological adaptation of human mechanism to the mechanics of industry. Taylor's axiom was that for

every operation a worker has to carry out the 'one

best way'. The worker has to do his work in accordance with the 'best norms', thereby economising

motion, time and the money of the enterprise. In order

to encourage him to conform to the norms and to faster emulation, the worker is offered a system of

bonuses. Scientific labour management seeks to establish

the conditioned reflex, most profitable for the enterprise, to produce a human production automation

physically conditioned and 'stimulated' psychological

spring of prestige and material spring of the bonus16. And this brought the enterprise huge profits not

only by 'scientifically' exploiting the labourers

of their labour but also an attendant process of capitalist division of labour resulting in deskilling that

conditioned the physical and mental faculties

of human beings for the sole purpose of profit-making. Taylor's "Bethlehem Steel Experiments" proved

this point more than sufficiently. The table on the

next page shows his results.

Each worker who could handle 16 tons of iron ore on an average per day previously, was made to

handle 59 tons, an increase of about 270%. Average cost of

handling one ton of ore was reduced substantially, of course, with a meagre rise of about 63% in the

wages of the workers which is highly disproportionate

to the output. It may be noted here that "Taylorism" was widely prevelant in many industries in America

in the last decades of the l9th century. The implementation

of this principle, as Braverman has pointed out,

18

table with 3 columns and 5 rows

Old Plan

New Plan Task Work

1. The No. of yard-labourers was reduced from below

400&600

140

2. Average No. of tons per man per day

16

59

3. Average earnings per man per day

$ 1.15

$ 1.88

4. Average cost of handling a ton of 2240 pounds

$ 0.072

$ 0.033

table end

Source : Taylor, F.W., Principles of Management, Harper and Brothers. New York, 1911, p. 71.

resulted in "the dissociation of the labour process from the skills of the workers". Workers were made

"to depend not at all upon their abilities but entirely

upon the practices of management". Work under this system of 'scientific management' is in reality

mental and physical violence on the part of the capitalist

over the mass of workers. Studs Terkel in the introduction to his recent book has aptly described the

conditions of workers under such a system. To quote

him:

"This book, being about work, is by its very nature, about violence—to the spirit as well as to the body. It

is about ulcers as well as accidents, about

shouting matches as well as fist fights, about nervous breakdowns as well as kicking the dog around. It is

above all (or beneath all) about daily humiliations.

To survive the day is triumph enough for the walking wounded among the great many of us. . .

It is about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash for

astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for

a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying. Perhaps immortality too is part of the

quest. To be remembered was the wish, spoken or

19

unspoken, of the heroes of this book. . .

For the many, there is hardly concealed discontent. The blue-collar blues is no more bitterly sung than

the white-collar moan. "I am a machine" says the

spot-welder. "I am caged" says the bank-teller, and echoes the hotel clerk. "I am a mule" says the steel

worker. "A monkey can do what I do" says the receptionist.

''I am less than a, farm implement" says the migrant worker. "I am an object" says the high-fashioned

model. Blue-collar and white call up on the identical

phrase, "I am a robot". . .

Nora Watson (an interviewee) may have said it most succinetly. 'I think most of us are looking for a

calling, not a job. Most of us, like the assembly line

worker, have jobs that are too small for our spirit. Jobs are not big enough for people".17

Such is the origin and nature of Taylor's scientific management of the process of production under

competitive capitalism where human beings are transformed

into automations by way of deskilling them through the process of capitalist division of labour. They are

reduced to be a part of 'factors of production',

'personnel' and lastly, a 'resource'. The verb to manage was derived from manus. the Latin for hand,

originally meant to train a horse in his paces, to

cause him to do exercises of the manage.18 In a word, it is a process of dehumanizing the human

beings. People become neurotic. The author of the 'theory'

F.W. Taylor himself was, it appears, "at the very least, a neurotic crank".19

IV

Under capitalism, men are reduced to the status of commodities. However if the commodities (lifeless

products) cannot resist this reduction, David Wells

pointed out, men can and do. The impossibility of reducing workers to mere automata, together with

capital's ever renewed drive to achieve this reduction,

is the fundamental contradiction underlying class-struggle in capitalism.20 In the last half of the 19th

century, America had witnessed a spate of trade

union

20

movements, working class unrest, agitation for higher wages, reduction in working hours and better

living conditions.21

Given the state of dehumanization of the working class and growing trade union movement the results

of Taylorism— new problems of management and organisation

arose in the capitalist industry in the west especially in America, the first decade of the 20th century.

The industry summoned sociologists to investigate

into the problems of industrial unrest and to suggest measures for increasing productivity and efficiency.

Elton Mayo, a professor in industrial sociology

at Graduate School of Business Management, Harvard University, who carried his research with the

support of Rockfeller and Carnegie Foundation Grants,

was one of the important sociologists who came to the rescue of the industry. Mayo and his colleagues,

concentrating mainly on the behaviour of the workers

and their productive capacity, keeping in view physiological, psychological, physical and economic

aspects, came out with the conclusion through their

'Hathorne studies' that the whole problem is one of 'human relations'. For them, the whole problem

appeared as a problem of human attitudes and sentiments,

not capitalist social relations of production. To them, what matters in industrial efficiency or inefficiency,

increase or decrease in productivity was

individual's psychological make-up. For this, what is required is a kind of 'psycho-therapy'. No wonder it

is called 'clinical' approach.

Thus the capitalist relations of production firstly reduces the workers to be psychos, it then examines

the psychology of the workers to adapt them by odious

means to industry for efficiency and productivity. So much for the theory. Any way, it is because of these

efforts by the "cow sociologists" like Elton

Mayo, that industrial sociology (that tries to find humanism in already dehumanised workers), industrial

psychology (that tries to find a normal being

in a worker who was already a neurotic crank) and industrial and organisational consultancy (an immoral

act of sharing in capitalists' decision-making)

came to the fore as separate disciplines to rescue capitalism from outside as it was already endangered

from within. And the 'human relations school'

21

had emerged within the management and organisation theory as a distinct approach. This school was

severely criticised by the later writers on organisation

and management. According to McGregor, these ideas on organisation and management presume that

most people must be coerced, controlled, directed, threatened

with punishment to get them to put forth adequate efforts toward the achievement of organisational

objectives.22 Argyris, another writer, had commented

that the present organisational strategies developed and used by administrators (be they industrial,

educational, religious, governmental or trade union)

lead to human and organisational decay.23 However, the ideas proposed by these critics are in no way

different in that they are indeed intended to help

the management against the interests of the workers albeit in a different manner.

Capitalism treats the individual as the "ultimate entity". It reduces the multifarious relations in society to

just one sort; the mere interdependence of

abstract labour, expressed in the cash nexus. Here people figure not as in the feudal mode of production

as tenants, vassals, burghers, freeholders and

guildmen, or indeed as friends, members of different communities, political allies or opponents etc., but

first and foremost as owners of commodities of

certain value. People are treated without regard to their specific qualities but as 'men'. The process of

market exchange is such that each looks only

to his own advantage, thereby treating his commodities as private property, as property which others

are excluded from controlling. It is worth noting

that the term "private" comes from the Latin "privare" meaning to deprive. Every exchange of

commodity accentuates the principle; mine ergo thine; thine

ergo mine. What is reciprocated is the exclusion of ownership. As owners of private property, therefore,

the equal "men" of commodity exchange are also

equally "individual" men who pursue interests exclusively their own."24 All 'individuals' are supposed to

'enjoy' in the words of Marx, "freedom, equality,

property and Bentham".-5 Freedom because both buyer and seller of a commodity . . . are constrained

only by their free will. They contract as free agents,

and the agreement

22

they come to, is but the form in which they give legal expression to their common will. Equality because

each enters into relation with the other, as with

a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property because each

disposes only what is his own. And Bentham because each

looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation with each

other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private

interests of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself about the rest, and just

because they do so, do they all, in accordance with

pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all shrewd providence work together to

their mutual advantage, for the common weal and in

the interest of all."26

The process of commodity exchange (i.e., capitalist system), says Marx, "furnishes the Free-Trade

Vulgaris' with his views and ideas and with the standard

by which he judges a society based on capital and wages . . . now strides in front as capitalist; the

possessor of labour power follows as his labourer.

The one with an air of importance, smirking, intent on business; the other timid and holding back, like

one who is bringing his own hide to market and

has nothing to expect but—a hiding.".27 In such a system "freedom, equality, property and Bentham"

means that the capitalist is "free" to buy the worker's

hide and the labourer is "free" to sell it; the capitalist and the labourer are "equal" because they

exchange equivalent for equivalent i.e., the wage

and the hide. Both possess "property" of their own—the capitalist of his capital and the labourer of his

flesh and blood; each of them bother about their

ownselves—the one to amass profits, the other for his physical survival. These are the individuals who

are considered as the ultimate entity in capitalism.

In a word, they are alienated persons, alienated from their social connection like separating the

umbilical cord and alienated ultimately from themselves.

All the writers on organisation and management from Taylor to Riggs have concentrated their attention

only on this individual person, though they talk about

"group", "cooperation" "coordination" etc.

23

Thus Chester I. Barnard an American business executive thought of organisation as a "cooperative

system" and what was needed accordingly was a "cooperative

social action". To him, organisation was "a system of consciously coordinated activities of two or more

persons".28 "It is a system composed of the activities

of human beings, a system in which the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts and each part

is related to every other part in some significant

way. As a system it is held together by some common purpose by the willingness of certain people to

contribute to the operation of the organisation".89

According to Barnard each individual by contributing his services to the organisation receives, imagine

what—nothing other than satisfaction. He disapproves

the 'theory of economic man' though nobody knows who proposed such a theory, even if there is such a

man where social relations are reduced to money relations

and the worker into commodity. Barnard, after 'demolishing' his imaginary 'theory of economic man'

proposes his own 'theory of contribution-satisfaction-equilibrium'.

Contributions which may be regarded in terms of organisation as activities, are possible only when it is

advantageous to workers in terms of personal satisfaction.

Barnard says "if each man gets back only what he puts in (recall Marx's ironical statement about

"exchange of equivalent for equivalent", i.e., the capitalist

his wages and the labourer his hide) there is no net satisfaction for him in cooperation. What he gets

back must give him advantage in terms of satisfaction,

which almost always means return in different form from what he contributes".30 For this purpose, he

proposed "incentives" such as material inducements

like money and opportunities for distinction, desirable conditions for work, ideal benefactions, pride and

workmanship, patriotism, loyalty to organisation

etc.

According to Barnard, the organisational "cooperative social action" consists in "a system of consciously

coordinated activities". And to achieve this goal

the organisation lures the workers by extending some "incentives"—he rightly called them

"inducements"—mostly non-material. This, in itself explains that

there has been no "cooperation" or

24

"coordination" in the organisation; and that it should be achieved by certain new techniques and

methods as the old techniques are no more useful.

In a society where private property determines the social relations every individual person is motivated

towards his selfish interests without any concern

for others. The individual persons can go to any extent to "satisfy" their selfish interests. This means

perpetual conflict, not "coordination". Those

who can get maximum "satisfaction" are those who possess more commodities viz. private property

under their control. In the perpetual conflict for achieving

"satisfaction", it is only Cromwells who win, not Charleses. Because the former would be a protege of

those 172 and odd most powerful trading families

who earned enormous wealth through piracy and slave trade in the 16th and 17th centuries and who

were eager to expand their business empire for which the

latter became a stumbling bloc. The attempt was in no way less than "a consciously coordinated social

action" but unfortunately for Barnard and also for

Charles, it was a civil war—an historically decisive civil war at which Barnards and Charleses were

doomed to loose. This is not to teach history to the

so-called 'organisation thinkers' for whom business is more important, but to demonstrate that in a

society divided into two warring classes "conscious

cooperative social action" is a dream. At the same time, however, this is doubtlessly possible at two

places, (i) among those who want to dominate by controlling

the entire means of production and who constitute a small minority for the purpose of exploitation of a

big majority since nothing less than this gives

them "satisfaction", and (ii) among the great mass of producers who always try to emancipate

themselves from such an exploitation.

Thus capitalism creates the contradiction in the absence of which it has no existence; at the same time it

makes attempts to pecify contradictory forces

namely, capitalists and workers without adversely affecting both the contradiction and the capitalists.

The so called theory of organisation of Barnard

had its origin in the latter part of this reality.

The spirit of the technique is to preach the worker to

25

"satisfy" himself by a sophisticated way of hiding and the capitalist to "satisfy" himself with the worker's

hide. Barnard advises the capitalist to teach

the worker "pride and workmanship" and also "patriotism" (whose recent Indian version is "Srma yeva

Jayate") for the purpose of a little painless hiding.

Thus Barnard's so-called theory of organisation is no more than another technique intended to maintain

and cement the exploitative social relations in

an organisation albeit in an apparently sophisticated guise namely, "cooperative action".

But a truely sophisticated theory of organisation can be found in a different and more acceptable

disguise namely 'objective social science' in Max Weber,

a German lawyer and an academic.

Among the numerous writers on organisation theory Max Weber was considered to have occupied a

unique place. His thought had combined in itself all the qualities

of science, religion, philosophy and polemic. Considered as "the St. Paul of the concept of bureaucracy

and capitalist rationality" there is a "dramatic

unity among all his concepts".31 He was shrewd enough to propose "a value neutral and objective social

science"38 which stands as a testimony to his class

nature,33 at the same time can declare unhesitatingly that "ideals ... are just as sacred to others as ours

are to us" (emphasis added).34 The "value neutral

social scientist" in Weber had conceptualised the "social conflict" as an "eternal" phenomenon.35 The

root cause for the "conflict", Weber theorised, was

"competition" for "domination".36 It consists "in physical strength, cunning, greater intellectual ability,

sheer lung power, a better demogogic technique,

greater ingenuity, flattery, a talent for intrigue".3' While characterising such "concepts" (as the one

mentioned above) as "mental constructs, not to

be found anywhere in reality",38 he did not hesitate to attack Rosa Luxemburg and her colleagues in the

German Social Democratic Party who were fighting

against the oppressive Prussian military autocracy (that means, according to Weber, creating conflict in

an

26

other-wise strong nationalist Germany) with all the derogatory phrases which he had mentioned above

in same verbatim while identifying the causes for the

"conflict".39 It is needless to say to whom Weber had attributed other soft phrases. George Lukacs

treated him to be "a prominent spokesman for the bourgeois

imperialism of Wilhelmine Germany", and Wolfgang Mommsen characterised him as one who was

committed "to the welfare of the German military imperialism",40

in whose military bureaucracy one finds Weber's ultimate identification of his "ideal-typical form as "the

highest social embodiment of rationality".41

Here one can make a brief attempt to examine the scientific validity or otherwise of Weber's theory of

organisation, on the basis of his writings.'12 Weber

used the German word verband, the most obvious translation of which is "organisation", to connote

different notions such as state, the political party,

the church, the sect and the firm. This word has also been translated as "corporate group". It is in this

context he discussed certain basic categories

of his philosophy such as "power", "authority" or "domination" etc.

As for the origin and nature of his concept 'organization' (verband), to Weber a person could be said to

have "power" (Macht) if within a social relationship

his own will could be enforced despite resistance. If this "power" is exercised for "the structuring of

human groups", it becomes a "special instance of

power", namely "authority" (Herrschaft). Thus he distinguished between "power" and "authority".

"Authority" or "domination", as it is distinctly known

is instrumental in the emergence of verband. The rules of an organisation Weber terms as

"administration". The most important aspect of the administration

was that it determines who was to give commands to whom. Thus, "every form of authority expresses

itself and functions as administration". To Weber, all

authority is "legitimate" because it is always founded on a "popular belief structure", people may

believe that obedience was justified because the person

giving the order had some sacred or altogether outstanding characteristic. This authority of the person

Weber calls as "charismatic authority". Secondly,

a command might be obeyed out of

27

reverence for old established patterns of order—"traditional authority". Thirdly, men might believe that

a person giving an order was acting in accordance

with his duties as stipulated in a code of legal rules and regulations. This was Weber's category of "legal

authority" to which he added "rational" character.

And this is his "ideal type" of "legal-rational" organisation which is the characteristic feature of modern

administration.

The whole thing can be reduced to the following:

(i) All persons possess "power",

(ii) "Power" by itself is not "authority": only "special instance of "power" exercised for the purpose of

"structuring human groups" can be "authority"

or "domination",

(iii) Social relationship is always one of a dominating and dominated character,

(iv) All authority is administration,

(v) All authority is "legitimate" because it is founded on certain belief structures; and lastly;

(vi) All "structured human groups" are organisations and hence 'personified authorities'.

Now let us examine the scientific validity of the theory as an explanation to social reality. We start with

the last point. Since it reduces the burden

of going into the remaining points which would prove to be trivial points, by themselves. Inspite of great

scientific researches going on in his lifetime

in social anthropology, Weber preferred to believe that organisation minus domination of a small,

powerful minority over a big majority, is a non-existent

phenomenon. What is more, he believed in its "legitimacy". After his life-long researches, living among

the American Indians, Lewis H. Morgan published

his historic findings43 when Weber was in the prime of his youth, zealously seeking knowledge about

social reality.

Morgan had found in the ancient Iroquois gens an 'organised' communitarian life with nobody

processing any kind of "special instance of power" i.e. authority

or domination. To quote Morgan; "All the members of an Iroquois gens were

28

personally free and they were bound to defend each other's freedom; they were equal in privileges and

in personal rights, the sachem and chiefs claiming

no superiority; and they were a brotherhood bound together by the ties of kin. Liberty, equality and

fraternity, though never formulated, were cardinal

principles of the gens. The gens was the unit of the social system, the foundation upon which Indian

society was organised. [This] serves to explain that

sense of independence and personal dignity universally an attribute of Indian character".41 It was an

organisation of society which as yet knew no special

authority, which as yet knew no state. But Weber did not bother about this which by then had already

known 'organised' communitarian social structure.

Men and women "differ in no way from one another, they are still bound to the umbilical cord of the

primordial community", commented Marx on the Iroquois

gens.45". . .it was broken by influences which from the outset appear to us as a degradation, a fall from

the simple moral grandeur of the ancient gentile

society. The lowest interests—base greed, brutal sensuality, sordid avarice, selfish plunder of common

possessions—usher in the new, civilised society,

class society; the most outrageous means—theft, rape, deceit and treachery—undermine and topple

the old, classless, gentile society. And the new society

during all the 2,500 years of its existence has never been anything but the development of the small

minority at the expense of the exploited and oppressed

great majority . . . ."46 What Weber simply did was attributing "legitimacy" to the selfish interests in the

"new society", as against the communitarian

interests. Though specialised in conceiving "mental constructs" his intellectual imagination could go only

to the extent of identifying the "conflict"

as an eternal phenomenon. At times, the social transformation had appeared to him as a "calling",

which centres its attention on the religious aspects

like 'Protestant ethic'.

To accept his concept of 'belief structures' on which the "authority" is supposed to have founded is to

deny the entire history of human development. In

what belief structure—tradition, charisma or law—does Cromwell fit in?

29

Even if people 'believed' in Cromwell's virtues, who were they? And even if all the people believed in the

virtues of Cromwell what was the basis for such

a belief? Nearer home, what was the belief structure that served the Iron Chancellor to "dominate"

imperial Germany? If people believed in either of these

belief structures, was it not tantamount to the view that people passively obliged to be dominated? If

so, is there any need for a belief structure at

all? If people believed in Bismarck's authority where was the necessity for ruthless repression on people

by means of iron laws? These are but a few questions

which Weberism refuses to answer. The intentions of his so-called "philosophy of history" as Weberism

is often called, were to legitimise authority or

domination and thereby charactise class-struggle and civil war as mere 'power polities'. He found such

politics among the German Social Democrats only

when his attempts to find a place in the party had failed him. The Prussian military bureaucracy had

appeared to him as "legitimate" and "rational". But

there was a challenge to this autocratic authority from the working class under the leadership of the

Social Democratic Party. It was in the politics of

Social Democrats that Weber found cunningness, demogogy, lung-power, intriguing etc., the reasons for

this were obvious.

Weber's persons, possessing "power" and in special circumstances possessing "special instance of

power" or "authority" are none other than the individual

persons, who 'enjoy' "freedom, equality, property and Bentham" in the society of commodity exchange.

The concept of abstract individual and the study of

his actions as socially isolated things such as psychological attitudes etc. is not only central to Weberism

but also to "all conventional Social Science

of "establishment"." And Weberians are conscious that without such an individual "sociology will seek in

vain to affirm its validity as an autonomous science".48

This is equally true of Weber's "philosophy of history".

But such an individual can be found only in myths, not in social science. "The lasting fascination of the

Robinson Crusoe myth is due to an attempt to imagine

an individual independent of society. The attempt breaks down. Robinson

30

is not an abstract individual, but an Englishman from York, he carries his Bible with him and prays to his

tribal God . . . (for) a new society".49 A social

scientist is expected to probe into the 'mysteries' of social reality. This is more binding indeed on the

'value-neutral' and 'objective social scientists'

like Weber. Mystifying social reality is the vocation of prophets. It is not difficult for one to understand

whether Weberism is a science or prophecy.

It is not for nothing that Weber, the "dead Saint" is resurrected in recent decades. It is the historical

necessity of imperialism which preaches myth

in the name of science. In his recent work, Rationality and Irrationality in Economics, Maurice Godelier

had successfully proved not only the irrationality

of Weber's 'rational' philosophy but also the irrationality of the bourgeois social theory as a whole.50

VI

With the Second World War, capitalism had entered a new crisis. In fact, the war itself was the result of

a big crisis— the depression of 30s. The working

class, far from being a passive lot, had already developed into an organised force throughout the world.

With this, there arose new problems requiring

new methods and techniques for the purpose of successfully running the gaint western capitalist

organisations of the corporate business across the world.

The success or failure of an enterprise largely depended on thoroughly calculated, timely decisions

pertaining to various aspects of the organisation.

Thus, emerged the 'decision-making theory' whose apostle was Nobel laureate Herbert Simon. The

theory had its origin in the rediscovery of Comtean "positivism"

of the early 19th century. Auguste Comte, whom some hold as "god father of sociology", unlike a

majority of his contemporaries who rejected the rational

humanist spirit of the French Enlightenment, rejected also the achievements of the 17th century, of the

Renaissance and the Reformation. The core of his

vision of society lay in the marriage of modern capitalist industrial production forces with the kind of

social and political relationships which obtained

at the peak of theocratic feudalism. To achieve this end, he proposed the establishment

31

of a caste of scientist priests whose function it would be to endow the industrial and other secular

authorities with the unquestionable transcendental

sanction they intrinsically lacked. The ideological weapon to combat this, was positivism51 It was the

positivism of Comte which behavioralists like Talcott

Parsons made the foundation for their 'theory'. Simon had successfully injected this into his model of

'decision-making' in organisations.

Positivism, to which Simon refers, separates factual propositions and value judgements as if they are

unrelated aspects. According to him, "the former is

validated by its agreement with the facts, the latter by human fiat".52 He contends that every decision

contains "an ethical as well as a factual content"

in it. "The basic value criteria that will be employed in making decisions and choices among alternatives

in an organisation will be selected for the organisation

primarily by the controlling group—the group that has the power to set the terms of membership for all

the participants.53 Bureaucracy provides the facts

and the managers make decisions that best fulfil the values and objectives laid down by the controlling

group. Simon following Weber called this 'rationality'.

Thus bureaucracy which is expected to provide facts may put forward factual information pertaining to

the production needs of cheap and nutritious food

for the impoverished masses of the people. Along with this they may also provide facts pertaining to the

colour T.V. requirements of a small minority.

They may also gather facts pertaining to the purchasing capacity of both the sections and also about the

profits that would accrue to the organisation

if each of these is decided to be taken up. Managers take the decisions in accordance with the "value

criteria" primarily selected by the controlling group

that has the power to set the terms. Now, the 'rational value' of the decisions solely depends on the

values of the controlling group".

Recall the nature of the commodity exchange society; it would not be difficult for one to understand not

only the values of the "controlling group" but

the deceptively apodictic values of the facts themselves. And it is possible for one to understand then

who controls what, in what manner, why

32

and for what purpose. It is not difficult to understand the value orientation of the decisions as also the

intrinsic values of the facts.

Commenting on the 'rationality' of the "decision-making", Baran and Sweezy opined that "the nature

and volume of out-put, the technology employed, the investment

undertaken, the raw materials used, the prices charged—none of these, no matter how rational the

methods by which they were arrived at, can be thought

of as corresponding to the needs of society as a whole or even as reflecting the growth of the forces of

production in one of the component parts. It is

as if a superbly skillful typist operating a perfectly faultless electric type-writer were set to work,

enjoined to avoid a single typographical error

because one hundred type written pages proof read and free of mistakes have to be ready for delivery

promptly at 4.00 p.m. to the janitor for removal to

the dump.54

Further, a decision can be said to be 'objectively rational' only if it is the correct behaviour for

maximising given values in a given situation. For the

purpose of enhancing this 'rationality' what is required, according to Simon, "was training and

indoctrination so that the organisation's criteria of decision

are injected into the very nervous system of the organisation members".

This is nothing less than training the members of the organisation to arrive at decisions which are

apparently apodictic in nature. This is possible because

positivism treats facts as 'givens', as eternal which in fact they are not. The eternal nature of the "facts"

proves itself to be a dubious one and an

outright deception when we come to know that poverty and affluence are not eternal but man made.

The tasks of decision-making lie in the best use or rather

best manipulation of these apparently value neutral facts to fulfil the organisation's goals. The question

of good or bad, morality or immorality does

not arise; what is important is the goals of the organisation, i.e., making more profits.

Outwitting Machiavelli, Simon says that "the terms good and bad when they occur in a study on

administration are seldom employed in a purely ethical sense.

Procedures are termed good when they are conducive to such attainments.55

33

Simon's indifference for ethical values in decision-making can be regarded at the very least as

rationalisation of immorality or at best, as intended to

absolve the decision-makers of their immoral activities—an unavoidable 'fact' in capitalism.

Thus the theory of decision-making, intended to rationalise organisational activity, had proved itself to

be a theory of rationalisation of capitalist immorality.

VII

'Developmental approach' is the latest one in the development of administrative theory. The process of

decolonisation following the II World War resulting

in the establishment of independent states, put a full-stop to the naked exploitation of the colonial type.

The emergence of the capitalist and communist

blocs had thrown two models for the development of the newly emerged nations. The growing

awareness of the people in these countries about the vagaries

of capitalism and imperialism resulting in backwardness and underdevelopment, and their growing

vulnerability for mass revolutions with the help of the

communist bloc had forced the west and its administrative thinkers to come out with new theories of

'development'.

A number of western social scientists have begun to study development politics, economics,

administration and so on. The Comparative Administration group

of the American Society for Public Administration consisted largely of scholars who had served on USAID

missions. The theory of 'development administration'

was put forward mainly by these scholar-bureaucrats, namely, Riggs, Weidner, La Palombara, Diament

and Pye.56

'Development' according to their 'theories' meant westernisation i.e. industrialisation or modernisation.

The underdeveloped countries, according to this

theory, have no scope for development without undertaking massive industrialisation of their societies.

Massive industrialisation is not possible if they

do not seek financial and technological aid from the developed countries of the west. 'Development' in

various spheres of national life was thus linked

to external aid. This is nothing but capitalist development. In the sphere of

34

economics, it may be a transfer of 'green revolution technology' intended to transform the entire

agriculture into capitalist industry the sole aim of which

is opening the doors of the underdeveloped countries for multinational corporations to 'supply' the

required inputs. In the sphere of politics it may be

transfer of ideas for 'nation building' activities for which the theory suggests "greater differentiation and

specialisation", "greater scope for the private

sector, more achievement orientation and recruitment increasingly on the basis of achievement criteria

instead of ascriptive ones". Lastly, if these countries

wish to develop like those in the west they have to undergo and experience all those historical phases of

'development' in the west which may take a few

hundred years.

The whole thing boils down to only one thing that these erstwhile colonies should look forward to west

and its capitalist development as the ideal type;

that they have to go a long way in a phased manner overcoming the transitional problems such as

corruption, authoritarianism, ineffectiveness and dehumanisation

to achieve the status of a developed country. These 'developmentalists' show Britain as the model

which, according to them, took six hundred years to reach

the present stage of development.

One may however ask whether these western countries had no colonies for over a period of 200 years

for ruthless exploitation of wealth and cheap labour

that helped the western metropolis to develop. How do they expect the underdeveloped, erstwhile

colonies to develop without such facilities atleast for

the same period of 200 years. Anyone who asks such questions would be looked upon as doubting

Thomases who always talk about 'perverted' things like exploitation,

leaving out 'progressive' things like 'development'.

VIII

Thus, these theories which have emerged whenever there arose crises in the western capitalist set-up,

have hardly any difference in the spirit and content

capitalist in content and exploitative in spirit. Whenever there developed a new crisis

35

in the system, the theory, in response to the crisis, had developed new skills and techniques to

overcome it by means of studying the administrative structures

and their functioning. So long as there arose manageable problems, these skills and techniques could

serve capitalism as palliatives. When capitalism reached

its highest stage i.e., imperialism, resulting in mass upsurges and revolutions throughout the world,

these theories failed to cope with the situation

and proved to be obsolete. Thus the crisis in capitalism once again reflected in the field of administrative

theories. The theory like its material base

namely imperialism had reached a state of impasse.

Thus in the epoch of imperialism the 'theory of administration' had lost its relevance as an explanation

to social reality and proved its uselessness for

its criticism. This is because the theory had not contained any scientific validity to be a social theory. At

best it had certain methods and techniques

for dominating the working class in capitalist Society.

It is at this stage, the students of administrative theories have begun to search for a 'realistic' theory of

administration. Interestingly they found it

in Marxism and Leninism. Certain ideas of Marx on Paris Commune were taken to be his "theory of