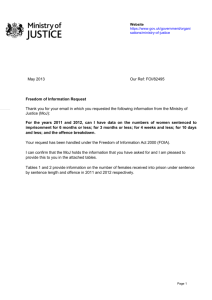

notes 4 (2012)

advertisement