Lecture 4 From Cradle to Grave

advertisement

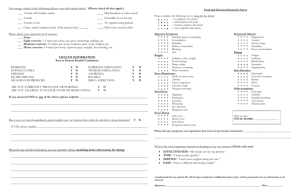

Lecture 4 From Cradle to Grave Medicine at School Topics • Liberal Reforms • School Meals • School Medical Inspection • Schools as Sites of Health – Games and Sport – Domestic Science – Sex Education Themes • State – parents – children: who is responsible for health? • School as a new site of health interventions • Visibility of school children and their health problems Liberal Reforms • The Liberal welfare reforms (1906-14) were acts of social legislation passed by the Liberal Party after the 1906 General Election. Argued that this legislation marked the emergence of the modern welfare state in the UK. Outlook shifted from laissez-faire system to more collectivist approach. • The Liberal welfare reforms took place after a Royal Commission on the country's Poor Law provision. Two contrasting reports known as the Majority Report and the Minority Report were published. As they differed so greatly the Liberals were able to ignore both reports and implement their own reforms. Implementing the reforms outside of the Poor Law, meant that the stigma attached to claiming poor relief was removed. • During the 1906 General Election campaign neither of the two major parties made poverty an important election issue and no promises were made to introduce welfare reforms. Despite this, when the Liberals led by Henry Campbell-Bannermann and later Herbert Asquith won a landslide victory they immediately began introducing wide ranging reforms. Spurs for Reform • Emergence of New Liberalism (e.g. David Lloyd George) • (Genuine) concern about poverty influenced by social inquires e.g. Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree • Threat of Labour Party and trade unions • Concerns about physical (and mental) deterioration (Boer Wars) • Example of public health – often on local scale – idea this could be implemented nationally and more broadly Areas of reform • • • • • • Birth 1907 the Notification of Births Act. Children 1906 free school meals, 1907 medical inspection. Elderly In 1908, pensions were introduced for those over 70. They were paid 5s a week (average wage of a labourer being around 30s a week) to single men and women and 7s 6d to married couples, on a sliding scale. The pensions were means-tested (to receive the pension, one had to earn less than £31.50 annually) and intentionally low to encourage workers to make their own provisions for the future. National Insurance/Health Insurance • 1911 National Insurance Act (Part 1) gave workers the right to sick pay of 9s a week and free medical treatment in return for a payment for 4d (the payments would last for 26 weeks of sickness). Medical treatment was provided by panel doctors. Doctors received a fee from the insurance fund for each panel patient they treated. The National Insurance Act (Part II) gave workers the right to unemployment pay of 7s 6d a week for 15 weeks in return for a payment of 2½d a week. • Compulsory health insurance for workers earning less than £160 per year. The scheme was contributed to by the worker who paid 4d, the employer who paid 3d and the government who contributed 2d. Scheme provided sickness benefit entitlement of 9s, free medical treatment and maternity benefit of 30s. • c.13 million workers came to be compulsorily covered. Children and Reform • In 1906, children were provided with free school meals. • Following an unfavourable report by the Board of Education's inspectors on infant education in 1906, school provision for children under 5 was restricted (previously, the normal age for the entry of working-class children into full-time education had been 3). • 1907 Medical inspections of schoolchildren introduced • In 1907, the number of free scholarship places in secondary schools was increased (paid for by the Local Education Authority (LEA)). • The 1907 Probation Act established a probation service to provide supervision within the community for young offenders as alternative to prison. • In 1908, the Children and Young Person's Act formed part of the Children’s Charter which imposed punishments for those neglecting children. It became illegal to sell children tobacco, alcohol and fireworks or to send children begging. Juvenile courts and borstals were created. Free school meals • After 1870s (elementary education compulsory) noticed increasingly that school children had too little food and clothing to attend school. • Plight of ‘half-timers’ – children who were still sent to work part-time or how had to assist at home e.g. ‘little mothers’ • Mid-1870s initiatives in some schools to provide meals – provided soup for small payment. • Mid-1880s Penny Dinners provided B’ham, Bristol and London (often given free or cheaper in practice). • 1888 45,000 children at 48 school boards in London dependent on school meals. • Voluntary sector heavily involved in local provision. Free school meals • 1906 Education (Provision of Meals) Act • Caused debate and dissension. Many local councils ignored this system, as it was not compulsory. • Made compulsory in 1914, in which year 14 million meals per school day were served (compared with 9 million per school day in 1910), most of which were free. In 1912, half of all councils in Britain were offering the scheme. Opposition to school meals provision • School meals recommended by 1904 Report on Physical Deterioration but not free school meals! • ‘The individual and the family, as well as for their own good as for the common good, should provide themselves with the necessaries of maintenance, by their own exertions and out of their own resources. By such action [introduction of free school meals] the motive for a sound and well-ordered family life is weakened… By a law of social development… the individual and the family under normal conditions have to maintain themselves…’ • B. Bosanquet, ‘Lectures on Charitable and Social Work’, 1901. Elimination of malnutrition • 1932 Board of Education claimed only 1% of schoolchildren malnourished. Chief Medical Officer claimed ‘the schoolchildren of this country are better nourished than at any previous time of which we have record’. • School milk scheme introduced 1934. • Yet great regional variation – many areas of high unemployment struggled to provide them e.g. South Wales. • Social surveys continued to show evidence of malnutrition e.g. John Boyd Orr claimed high incidence of rickets, dental decay and anaemia in 1936, and suggested 20% of children malnourished. Provision of meals and milk 1938 268 LEAs provided free school meals 635,000 receiving free milk 176,000 children getting free meals Yet did little overall to eliminate malnutrition or child poverty (John Welshmam) Medical inspection of school children • Origins of interest in medical inspection of schoolchildren in 1880s – interest in ‘bodily infirmity’ in schools. • After 1870s attendance compulsory and more children to observe and survey/anthropometric studies – – – – Over-pressure in school (Dr James Crichton-Browne) 1896 committee Mental and Physical Condition of Children Attracted interest of doctors, psychologists and educationalists Child Study Association/Childhood Society • 1890 London School Board appointed first school medical officer, Bradford 1893. • 1907 medical inspection of school children introduced poor families, however, could not afford doctors’ fees. • 1912 medical treatment was provided. However, education authorities largely ignored the provision of free medical treatment for school children. Health of school children • Poor to appalling – led to difficulties learning • Bad teeth • Defective eyesight • Poor hearing • Poor physical development 1909 in Stockport MOH inspected 4,000 children 59% had ‘various defects’ 600 dirty heads 800 ‘mouth breathers’ 300 heart disease and anaemia 65 ringworm and skin diseases Impact of School Medical Service • Inspections by doctors and nurses increased, school clinics established (supporters believed offered cheap and effective treatment to children, but GPs feared would rob them of fees). • Gradually expanded – by 1930s almost every LEA offered treatment for minor ailments, dental defects and defective vision. Most offered treatment for adenoids and tonsils, over half orthopaedic services and X-ray treatment for ringworm. Some offered artificial light treatment for rickets and other bony defects. • Meant many children could stay on at a normal school. • Also new treatments introduced e.g. artificial light for treating rickets, lupus and non-pulmonary TB. • Yet failed to tackle prevention, deficiencies in service and varied from locale to locale. Poorer areas with high unemployment spent less on school medical services, though needs greater. • See Bernard Harris, The Health of the Schoolchild (1995). Local authorities providing medical treatment Year Provision Clinics Hospital Spectacles 1908 55 7 8 24 1914 266 179 75 165 1917 279 231 95 223 1920 309 288 168 282 Number of LEAs between 328 and 317 Light therapy • ‘agreement is almost unanimous as to the tonic effect of ultraviolet radiation on debilitated children, [as] shown by their improved appetite, activity and nervous stability’. (George Newman, Board of Education, 1928) Just poor children….? • E.B. Rheumatic. Heart weak. Gymnastics good for her, but she needs to be carefully watched. • L.B. Slight and delicate. R. lung not quite sound. Gymnastics very useful but care to be taken. • E.P. A nervous excitable child subject to headaches. Weak trunk muscles and chest habitually contracted... • 1880s, school girls aged 11-14: crooked spines, poor eyesight, anaemia, defective heart and lungs, poor physical development, varicose veins, stooped posture, rheumatic disease and TB. North London Collegiate School for Girls • 1880s introduced medical inspections and directed gymnastics for girls/pioneered sport in school under headmistress Frances Buss and medical inspector Frances Hoggan Schools as sites of sport, exercise and remedial medicine • Attempts to introduce exercise to schools of all kinds • For boys from mid-19th, and girls towards end of 19th century – in schools for middle- and upper-class wide range of sports • For poor ‘drill’ more common • Martina Bergman Ősterberg, Superintendent of Physical Education London School Board in 1880s recommended Swedish system or Ling gymnastics her work frustrated by poor physical state of pupils • By 1909 London School Board included marching, dancing, skipping and gymnastic games • Physical education – connected to interests of state and citizenship (John Welshman) Sport, manliness and Empire Girls, Empire, sport and motherhood • Warnings of over-exertion • Dr Mary Scharlieb – excessive athletics could produce a ‘neuter’ type of girl • Sara Burstall, headmistress Manchester Girls School ‘They have only a certain amount of available energy’. Margaret Macmillan • Camp School at Deptford in London around 1910. • Remedial gymnastics and provision of meals in garden setting to intensely deprived local children. • Also offered minor treatment such as removal of adenoids, dental and minor surgical treatment. Domestic science • Complex relationship between girls and education – teaching domestic skills and broader education • Girls as future home makers/mothers (national efficiency) • 1878 teaching of domestic economy compulsory for girls; grants for teaching cookery 1882, laundry 1890 • Teaching of domestic science increased in importance in elementary schools 1880s and 1890s • Concerns about industrial employment for poorer girls and for better off women new opportunities in professions – deskilling for both! • Effort to make domestic skills more scientific – emphasis on nutrition, public health, hygiene, scientific practice of housework - contributing to home, community, nation • 1896 Association of Teachers of Domestic Science established (archives in Modern Records Centre at Warwick) Domestic science Health education/Sex education • Increasingly schools seen as appropriate places for dissemination of health education and sex education. • Again debate about who was responsible for such interventions. Role of parents, school or state. • Controversy in 1940s about introduction of sex education in schools • Many pupils reported ‘Oh no, nothing, we didn’t learn anything’ – sex education often incidental rather than part of curriculum and emphasis on VD. • Reticence amongst teachers about providing sex education – and amongst children. Often taught indirectly as part of biology or botany. Maggie Thatcher Milk Snatcher Conclusions • Thatcher’s actions reignited debate about who is responsible for health of school child as well as who should pay for provisions. • Late 19th century for multiple reasons saw creation of set of interventions for school children by state – debate about who should pay, how extensive interventions should be. • Poorest areas where need greatest often had weakest provision. • Also underlines shift from child as worker to child to school child and the emotional value of children, as well as their future worth to the state. • Schools came to provide a wide range of health and medical provisions: medical inspection, milk and meals, exercise and sport, domestic science teaching, sex and health education and special interventions, notably vaccination.