An Integrative Semiotic Framework for IS Research

advertisement

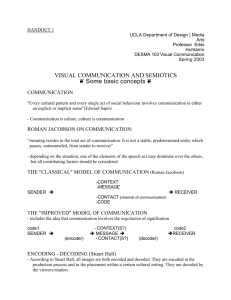

Interrogating Sociomateriality: An Integrative Semiotic Framework for IS Research John Mingers, Kent Business School Leslie Willcocks, LSE LSE Seminar June 17th 2014 Overview • What is sociomateriality? • Developing the framework: 1. Underlying philosophy: critical realism 2. Peirceian Semiotics 3. Information and meaning 4. Embodied cognition 5. Habermas’s theory of communicative action • Integrative semiotic framework • Illustrative examples • Critique of sociomateriality • Conclusion Sociomateriality Interrogating Sociomiality: An Integrative Semiotic The two most distinctive characteristics of humans as a Framework for IS Research species are: The ability to use language to co-ordinate actions: communication – which is primarily social based on meaning and signification The ability to develop tools to shape the environment: technology – which is generally realised physically Within information systems this is recognised as “ICT” – technology applied to information and communications. But what is the relationship between the social and the material? A. One system is dominant – e.g., technological determinists vs social of technology (SCOT) Professor Johnconstruction Mingers B. School Two interacting systems – e.g., socio-technical systems Kent Business C. The two systems are so intertwined they cannot be separated – UK sociomateriality, e.g., actor network theory, Barad, Orlikowski August 2013 “Agencies of observation … signals the inseparability of the material and semiotic apparatuses .. The material and semiotic apparatuses form a nondualistic whole” (Barad 1996, p. 172) “… on my agential realist elaboration, phenomena do not merely mark the epistemological inseparability of ‘observer’ and ‘observed’; rather phenomena are the ontological inseparability of agentially interacting ‘components’” (Barad 2003, p. 815) “There is no social that is not material and no material that is not social” (Orlikowski 2007, 1437) “In other words, entities (whether humans or technologies) have no inherent properties, but acquire form, attributes, and capabilities through their interpenetration. This is a relational ontology that presumes the social and the material are inherently inseparable.” (Orlikowski and Scott, 2008, p. 455). Developing the Framework I: Underlying Philosophy: Critical Realism We are dealing with distinct ontological domains – the social/cognitive and the material – which critical realism can accept (Bhaskar, Archer, Mingers) Accepts the ontological reality of a variety of different entities, physical, social, cognitive with different forms of epistemological access Transitive and intransitive domains of science The Real, the Actual and the Empirical Generative rather than Humean causality Epistemic but not judgemental reality Developing the Framework II: Semiotics Semiotics or semiology: the study of signs and systems of signification where a sign is an event, an object, a symbol or a behavior that represents something other than itself. Signs depend upon a shared set of meanings within a particular community and are the basis of all communication, whether linguistic or not. Semiotics studies the processes that lead signs to have particular meanings, and the ways in which such meanings are communicated and have effects. Thus, semiotics can be seen as the most fundamental of the social sciences since it underlies all communication and social action. Saussure: rests on a dyadic relationship between signifier and signified Peirce: involves a triadic relationship between signifier (representamen), signified (interpretant) and referent (object) Representamen icon, index, symbol The sign Object Interpretant •Immediate object as represented within the sign •Dynamic object as implied by or generating the sign •Immediate interpretant – direct meaning of the sign •Dynamic interpretant – the effect of the meaning on an interpreter •Final interpretant – the eventual effect after unlimited semiosis Figure 1 Pierce’s Semiotic Traingle Further Developments in Semiotics Charles Morris characterised semiotics in terms of three dimensions: Syntactics – the relations between signs, rules of language Semantics – the relations between signs and their objects and interpretants Pragmatics – the origin, use and effects of signs This was later used by Habermas in the theory of communicative action Roman Jakobson saw that Saussure’s distinction between the syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes of meaning were essentially similarity and contiguity or metaphor and metonymy Also developed a model of communication with six components: Addresser, addressee, message, context, code and physical or psychological contact Applications in Business and ICT Stamper’s semiotic framework – organizational semiotics Material (physical), empirical (transmission), syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, social Semiotic analyses of ICT as a communicational tool – Web 2.0 (Warschauer), hypertextuality in the WWW (Tredinnick), Tian (e-mail use), information (Mingers, Beynon-Davies) HCI – computer semiotics (Andersen), semiotic engineering (de Souza, O’Niell) Marketing (Mick, Arnold, Harvey), letters to shareholders (Fiol), decoding regulation reviews (Cooper). Developing the Framework III – Information and Meaning How do signs and symbols come to have meaning? We need to distinguish between information and meaning. Following several authors (Dretske, Mingers, Floridi), “(semantic) information is the propositional content of a sign or message” – that which is implied by the existence of the sign.” This means that information is objective and true for it to be information (as opposed to misinformation or disinformation) “Meaning” has two senses: (i) the system of meanings (connotations) that allows the signs to have a sense, and that basic sense (direct interpretant) (ii) The particular meaning (import) that the signs have for the receiver (dynamic interpretant) So, the meaning for an individual is partly subjective and leads eventually to (in)action Illustrative example – Khipu and the Inka Buraucracy (Beynon Davies 2012) Developing the Framework IV – Meaning and Embodiment How does meaning get created and translated into actions (embodied cognition)? And how do actions and information get transmitted (technology)? The process by which information is converted to meaning and that then results in action has been called embodied cognition (Heidegger, MerleauPonty, Mingers, Maturana, Dourish, O’Neill), what Peirce called “habits” “There is not thought and language … Expressive operations take place between thinking language and speaking thought; … It is not because they are parallel that we speak; it is because we speak that they are parallel … I do not speak of my thoughts; I speak them and what is between them.” (Merleau-Ponty, 1964, p. 18, orig. emphasis) Illustrative examples: work on human computer interaction e.g O’Neill 2008 embodimant and presence in virtual worlds e.g Schulze 2010 “It is rather stormy” Immediate object: wanting to know how the weather is Meaning 1: Understanding, Immediate interpretant Dynamical object: the addresser has looked out of the window Addresser Meaning 2: Connotation, Dynamical interpretant Addressee Meaning 3: Intention, Final interpretant Meaning 2: Generation, Dynamical object “Iet’s not go today then” Meaning 1: Action, Immediate object Embodied cognition Figure 2 Stages in the Interpretation of and Response to Signs Developing the Framework V – Habermas’s Theory of Communicative Action Habermas argues that communications (speech acts) raise validity claims with respect to three different worlds: The material world: truth about matters of fact in the objective world The social world: rightness about agreed norms of behaviour in our social world The personal world: sincerity about feelings and beliefs in my personal world These are analytical distinctions but nevertheless point to domains with substantively different ontological and epistemological characteristics Integrative framework: Semiosis and the Three Worlds Personal Intent, Import Semiosis Connotation, reproduction Social Representation, transmission Material “Sociomateriality” Figure 3 The Relations Between Semiosis and the Three Worlds Illustrating the Potential of the Framework (1) 1. Trip Advisor – study by Scott and Orlikowski, 2009 on-line travel community with reviews and opinions The study asks questions from a social-materiality perspective but very pertinent questions can also be asked from the personal-material, and the personal-socia, and how these relate to semiosis e.g.: • How do individuals relate to the technology? • How do they use it? Why do they use it? • Is it only extreme experiences that get recorded? • Level of belief on accuracy and validity? • What determines personal use? • How does the personal influence the social facts created? • Are actual experiences more convincing than statistical data? • Does social media change meaning, the flow of informaiton, and create ratings/assessment as facts? • What is the role of signs in creating a continually remade and contested social and personal reality? Illustrating the Potential of the Framework (2) 2. Dairy Production Plant – Kallinikos, 2011 Workings of a full computerized dairy production plant, and the role of semiotics Documents changes in the nature of work, personal-social-technological interactions Records how process operators seemingly needing to turn their back on the physical Production process and devote themselves instead to the task of examining the very structure of signs, codes and symbol schemes whereby physical relationships were mediated and regulated. Fragmented system of signs and codes that saw little relationship between token and referent. Critique of Sociomateriality Inherently self-contradictory: how can we discuss “humans” and “technologies” if they are inherently inseparable? Reduces two distinct but interacting structures to a duality that loses sight of both its components Lack of depth ontology which allows for emergent properties generated by the interaction of lower level mechanisms Reduces and emasculates the active agency of subjects without whom neither society nor technology would occur (the personal world) Reduces the role of semiosis as the process and the mechanism through which meaningful human interaction occurs. Technology is both the medium of semiosis, but also a condition for and the result of semiosis. Conclusion Semiosis becoming central in conditions of accelerating virtualization, abstractness, and modes of representation driven by advances in technologies, media and software. ‘Sociomateriality is always being enacted, performed and in the making. But… two other relationships – of sociation and embodiment – also need to be addressed on a more precise basis, and semiosis needs to play a central, explicit, rather than implied, part in the study of contemporary ICTS’ – Mingers and Willcocks, 2014 References Archer, M., R. Bhaskar, A. Collier, T. Lawsonand A. Norrie. 1998. "Critical Realism: Essential Readings," London, Barad K, 1996, “Meeting the universe halfway: realism and social constructivism without contradiction”, in Hankinson and Nelson (eds) Feminism, science and the philosophy of science, Kluwer, p. 161-194 Barad, K. 2003. "Posthumanist performativity: Towards an underrstanding of how matter comes to matter," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28, 3, 801-831. Barley, Stephen R. 1983. "Semiotics and the Study of Occupational and Organizational Cultures," Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 3, 393-413. Beynon-Davies, P. 2010. Significance: Exploring the nature of information, systems and technology, Palgrave macmillan, London. Bhaskar, R. 1978. A Realist Theory of Science, Harvester, Hemel Hempstead. Bhaskar, R. 1979. The Possibility of Naturalism, Harvester Press, Sussex. Bhaskar, R. 1993. Dialectic: the Pulse of Freedom, Verso, London. de Saussure, F. 1960 (originally 1916). Course in General Linguistics, Peter Owen, London. de Souza, C. 2005. The Semiotic Engineering of Human-Computer Interaction, MIT Press, Cambridge MA. Dourish, P. 2001. Where the Action Is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction, MIT Press, Cambridge, Ma. Dretske, F. 1981. Knowledge and the Flow of Information, Blackwell, Oxford. Fiol, C. Marlene. 1989. "A Semiotic Analysis of Corporate Language: Organizational Boundaries and Joint Venturing," Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 2, 277-303. Floridi, L. 2011. The Philosophy of Information, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Habermas, J. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action Vol. 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, Heinemann, London. Habermas, J. 1987. The Theory of Communicative Action Vol. 2: Lifeworld and System: a Critique of Functionalist Reason, Polity Press, Oxford. systems," Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 2, 1/2, 1-64. Jakobson, R. and M. Halle. 1956. Fundamentals of Language, Mouton, The Hague. Leonardi, P. 2013 “Theoretical foundations for the study of ‘sociomateriality’”, Information and Organization 23, 59-76 Maturana, H. and F. Varela. 1980. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living, Reidel, Dordrecht. Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception, Routledge, London. Merleau-Ponty, M. 1964. Signs, Northwestern U. Press, Evanston. Mick, David Glen. 1986. "Consumer Research and Semiotics: Exploring the Morphology of Signs, Symbols, and Significance," Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 2, 196-213. Mingers, J. 1980. "Towards an appropriate social theory for applied systems thinking: critical theory and soft systems methodology," Journal Applied Systems Analysis, 7, April, 41-50. Mingers, J. 1995a. "Information and meaning: foundations for an intersubjective account," Information Systems Journal, 5, 285-306. Mingers, J. 1995b. Self-Producing Systems: Implications and Applications of Autopoiesis, Plenum Press, New York. Mingers, J. 1996. "An evaluation of theories of information with regard to the semantic and pragmatic aspects of information systems," Systems Practice, 9, 3, 187-209. Mingers, J. 2001. "Embodying information systems: the contribution of phenomenology," Information and Organization, 11, 2, 103-128. Mingers, J. 2004c. "Real-izing information systems: critical realism as an underpinning philosophy for information systems," Information and Organization, 14, 2, 87-103. Morris, C. 1938. "Foundations of the theory of signs," In International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, O. Neurath (Ed.), 1, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Mutch, A. 1999. "Critical realism, managers and information," British Journal of Management, 10, 323-333. Mutch, A. 2013 “Sociomateriality – Taking the wrong turning?”, Information and Organization 23, 28-40 O'Neill, S. 2008. Interactive Media: The Semiotics of Embodied Interaction, Springer-Verlag, London. Orlikowski, W. and S. Scott. 2008. "Sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization," Academy of Management Annals, 2, 1, 433-474. Peirce, C. 1878. "How to make our ideas clear," Popular Science Monthly, 12, January, 286-302. Peirce, C. 1931-1958. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (8 Volumes), Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Pinker , S. 2008. The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature, Penguin, London. Ramussen, J. 1986. Information Processing and Human-Machine Interaction, North Holland, Amsterdam. Scott, S. and Orlikowski, W. 2013, “Sociomateriality – taking the wrong turning? A response to Mutch”, Information and Organization 23, 77-80 Stamper, R. 1997. "Organizational semiotics," In Information Systems: an Emerging Discipline?, J. Mingers and F. Stowell (Ed.), McGraw-Hill, London, 267-284. Stamper, R. 2001. "Organisational semiotics: Informatics without the computer?," In Information, Organization Tredinnick, L. 2007. "Post-structuralism, hypertext, and the World Wide Web," Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives, 59, 2, 169-186. Varela, F., Thompson, E. and Rosch, E. 1991. The Embodied Mind, MIT Press, Cambridge. Volkoff, O., D. Strongand M. Elmes. 2007. "Technological embeddedness and organizational change,"