J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles - CTools

advertisement

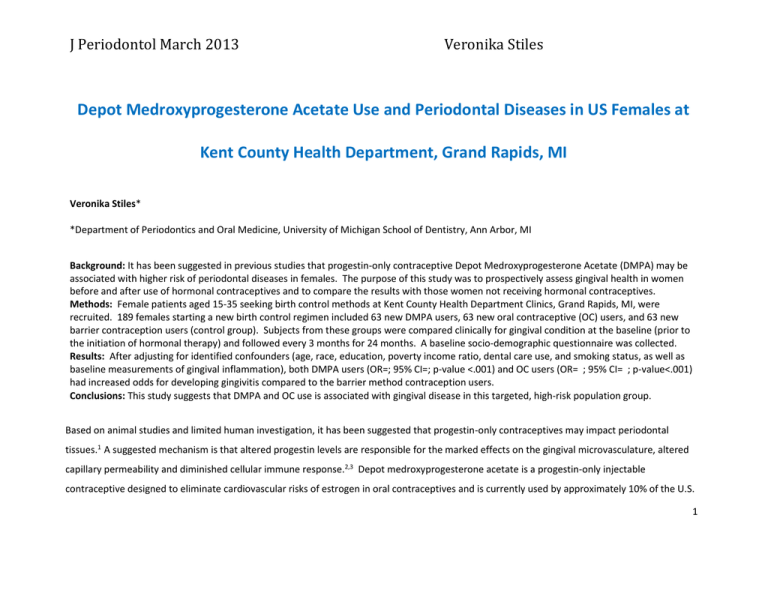

J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Use and Periodontal Diseases in US Females at Kent County Health Department, Grand Rapids, MI Veronika Stiles* *Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, University of Michigan School of Dentistry, Ann Arbor, MI Background: It has been suggested in previous studies that progestin-only contraceptive Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA) may be associated with higher risk of periodontal diseases in females. The purpose of this study was to prospectively assess gingival health in women before and after use of hormonal contraceptives and to compare the results with those women not receiving hormonal contraceptives. Methods: Female patients aged 15-35 seeking birth control methods at Kent County Health Department Clinics, Grand Rapids, MI, were recruited. 189 females starting a new birth control regimen included 63 new DMPA users, 63 new oral contraceptive (OC) users, and 63 new barrier contraception users (control group). Subjects from these groups were compared clinically for gingival condition at the baseline (prior to the initiation of hormonal therapy) and followed every 3 months for 24 months. A baseline socio-demographic questionnaire was collected. Results: After adjusting for identified confounders (age, race, education, poverty income ratio, dental care use, and smoking status, as well as baseline measurements of gingival inflammation), both DMPA users (OR=; 95% CI=; p-value <.001) and OC users (OR= ; 95% CI= ; p-value<.001) had increased odds for developing gingivitis compared to the barrier method contraception users. Conclusions: This study suggests that DMPA and OC use is associated with gingival disease in this targeted, high-risk population group. Based on animal studies and limited human investigation, it has been suggested that progestin-only contraceptives may impact periodontal tissues.1 A suggested mechanism is that altered progestin levels are responsible for the marked effects on the gingival microvasculature, altered capillary permeability and diminished cellular immune response.2,3 Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate is a progestin-only injectable contraceptive designed to eliminate cardiovascular risks of estrogen in oral contraceptives and is currently used by approximately 10% of the U.S. 1 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles contraceptive users aged 15-40.1 DMPA suppresses ovarian estradiol production. Estrogen depravation has been associated with tooth loss, alveolar bone loss, and clinical attachment loss; therefore, there is a possibility that the drug could adversely affect the periodontal structures.4,5 Furthermore, the majority of DMPA users are females of low socioeconomic status who are already at risk for the development of PD. The present study aims to investigate the effects of DMPA on periodontal health status of US females aged 15-35 who attend Kent County Health Department (KCHD) in Grand Rapids, MI. This study prospectively assessed gingival health in women before and after use of hormonal contraceptives and compared the results with those women not receiving hormonal contraceptives. METHODS Population This study assessed a population of five public health clinics operated by KCHD and supported one of its operational goals of improving health of women of childbearing ages. 6 The KCHD female population was targeted, because the majority come from low socioeconomic status and were already at risk for the development of PD. Eligibility Eligible females were ages 15-35 were pre-menopausal, and were willing to give consent to be a part of this study, which included a dental examination and questionnaire completion. Parental consent was required for women under the age of 18. Exclusion criteria included any medical conditions that precluded conducting an oral examination; being unwilling to stay in the geographical area for two years; pregnant or 2 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles planning to become pregnant within six months; under the care of a periodontist and/or using systemic antimicrobial agents; or having a medical diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa. Recruitment Recruitment at KCHD began in May 2012 and continued for 6 months. To reduce selection bias, recruitment was conducted after the patient had selected a form of birth control. Approximately equal numbers of women in each of three birth control groups were recruited: new DMPA users, new oral contraceptive (OC) users, and new barrier contraception users (control group). The investigator spoke to the potential participant at an appropriate time during their contraceptive appointment at the health department clinic. Study Design The women in the three birth control subgroups (DMPA, OC, and barrier) all followed the same protocol. At the baseline appointment, subjects were asked to fill out a self-administered questionnaire that asked about non-sensitive socio-demographic information. At the dental examination, diagnostic biomarkers of inflammatory tissue response and gingival disease indices were collected as outlined in Figure 1. Subjects were followed for the duration of 24 months and were clinically examined every 3 months in a manner identical to the baseline examination. Examination intervals were chosen with regard to the serum levels of progestin for DMPA users. The sample size of 189 women was chosen to provide a 95% confidence interval that there will be 20% difference among the three groups and will adequately allow for loss to follow-up. 3 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles Figure 1. Study Design Group 1 DMPA users; Group 2 OC users; Group 3 (Barrier Method) Clinical exam Plaque Index Gingival Index GCF-AST* GCF-ALP* Questionnaire* Baseline Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 3mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 6mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 9mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 12mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 15mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 18mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 21mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 24mo Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No *Clinical exam performed; Plaque Index, Gingival Index, GCF-AST, GCF-ALP collected at each of the listed time points *Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF); Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) *Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF); Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) *Baseline questionnaire collected information about patients’ age, race/ethnicity, marital status, parity, education level; dental care utilization, smoking status, alcohol consumption, perceived stress levels, and oral hygiene habits Data Collection Clinical Examinations Once the patient agreed to participate in the study and after filling out the self-administered questionnaire, an investigator conducted a 10minute clinical examination designed to minimize both disruption to the clinic schedule and patient burden. The examination involved a brief periodontal examination (i.e., assessments of dental plaque levels, gingival color assessment and bleeding on probing) and collection of gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) on 6 teeth. As adjunct diagnostic tools to the clinical examination, the levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and 4 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) in GCF were measured. Criteria for gingivitis were those used by National Center for Health Statistics for the NHANES III. Gingivitis was defined as presence of bleeding on probing and follows the scoring system: 0=No bleeding; 1=Bleeding, and Y=cannot be assessed (e.g., missing, partially erupted, or deciduous teeth). Examinations were 10 minutes in length and were conducted by one examiner. All patients were re-examined at each time point by the same examiner who was blinded to the birth control method. Questionnaire At the baseline, each participant completed a self-administered questionnaire that asked about non-sensitive demographic information, dental care utilization, tobacco use, perceived stress levels, and oral hygiene habits. The participants were asked to complete the questionnaire before leaving the clinic and instructed to place the questionnaire in the appropriate place. 5 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles STATISTICAL ANALYSES Univariate statistics were calculated for all variables to describe their distributions. Measures of unadjusted association between gingival bleeding and other covariates were assessed using Pearson correlation for continuous variables and chi-square trend tests for categorical variables. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple logistic regression modeling was used to assess the association between hormonal contraceptive use and measures of gingival disease status. The dependent variable for this analysis was gingival inflammation, dichotomized as present or absent. The covariates of interest were birth control group (3 categories), time from baseline (in 3-month intervals), and the interaction between birth control group and time. An interaction effect might be seen if, for example, gingival inflammation in the DMPA or OC group increased relative to the control group over time. A stepwise selection method was used to adjust for potential confounders, including the baseline value of gingival disease status, Gingival Index, Plaque Index, and levels of GCF-AST, and GCF-ALP. The method of generalized estimating equations (GEE) was used to account for the correlation of outcomes within an observational unit (i.e., follow-up time points for the same patient) in the estimation of the regression coefficients and their robust standard errors. Because level of education and poverty index were highly correlated, only poverty index was used when generating a regression model. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 statistical software. RESULTS The study sample included 189 non-pregnant, premenopausal females, ages 15-35, as shown in Table 1. The distribution of the subpopulation was ____% white; ____% were in 20-29 age category; ___% well-educated; ---% represented 1.31 to 3.49 poverty index level; ___% were not 6 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles married; ____% never had a child; ___% indicated current smoking, and ___% indicated a dental visit within the past 2 years. Using the study definition of gingivitis, ___% had gingival bleeding at the baseline. All demographic factors differed significantly between DMPA users, OC users, and barrier method contraception users, using the chi-square test for association (P<0.05). Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Females (aged 15 to 35) by Group Variable DMPA Users (n=63) (mean ±SE) OC Users (n=63) (mean±SE) BarrierMethod(n=63) (mean ±SE) Total (n=189) (mean±SE) Gingival Bleeding Yes No Plaque Index 0 0.1-0.9 1.0-1.9 2.0-3.0 Gingival Index 0 0.1-0.9 1.0-1.9 2.0-3.0 GCF-AST GCF-ALPGCF-ALP Age (years) 15 to 19 20 to 29 30 to 35 Race 7 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles Non-Hispanic White Hispanic Non-Hispanic Black Education Less than high school High School More than HS Family Poverty Level 0 to 1.3 1.31 to 3.49 ≥ 3.5 Marital Status Not married Married/cohabitating Parity 0 1 2 ≥3 Dental visit < 2 years Yes No Smoking Status Current Past Never The results of the multiple logistic regression (GEE) analyses presented in Table 2 indicate that, at a given population level, females using DMPA have increased odds (OR=___ ; 95%= ___to ___, p-value <0.001) of poor gingival health compared to the barrier method contraception users over the entire period of 24 months, after adjusting for baseline gingival disease, Gingival Index, Plaque Index, levels of GCF-AST and GCF-ALP, 8 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles race, age, poverty income level, dental use, and smoking status. There was a significant association between gingival inflammation and age, race, poverty index levels, and not having a dental visit within the past 2 years (Table 2). H0: The incidence of gingival inflammation does not change in the DMPA and OC study groups compared to the control group over the period of 24 months, after adjusting for identified confounders. Ha: The incidence of gingival inflammation changes in the DMPA and OC study groups compared to the control group over the period of 24 months, after adjusting for identified confounders. The QIC was used to choose the working correlation matrix in the estimating equation. As a result, exchangeable correlation structure was chosen. The interaction between time and DMPA use, as well as the interaction between time and OC use are shown in Table 3. In both cases, the odds of gingival disease increased in a linear fashion over time in comparison to the barrier group. 9 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles Table 2. Logistic Regression Model for Gingival Inflammation: Odds of Having Gingival Inflammation among KCHD Females (aged 15-35) 2012-2014 (n=189) Variable Group DMPA OC Barrier Method Gingival Bleeding Yes No Plaque Index 0 0.1-0.9 1.0-1.9 2.0-3.0 Gingival Index 0 0.1-0.9 1.0-1.9 2.0-3.0 Adjusted OR* 95% CI p-value I N/A N/A I N/A N/A I N/A N/A I N/A N/A 10 J Periodontol March 2013 GCF-AST GCF-ALP Age (years) 15-19 20 to 29 30-35 Race Non-Hispanic Black Hispanic Non-Hispanic White Poverty Index Level 0 to 1.3 1.31 to 3.49 ≥3.5 Dental visit <2 years Yes No Smoking Status Current Past Never Veronika Stiles I N/A N/A I N/A N/A I N/A N/A I N/A N/A I N/A N/A *Model adjusted for gingival disease status, GI, PI, GCF-AST, GCF-ALP, age, race, poverty income level, dental visit, and smoking status. 11 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles Table 3. Odds of Gingival Inflammation among Females (aged 15 to 35) per Year Over 24 Months Variable Adjusted OR* 95% CI p-value I N/A N/A DMPA OC Barrier Method *Model adjusted for gingival disease status, GI, PI, GCF-AST, GCF-ALP, age, race, poverty income level, dental visit, and smoking status. DISCUSSION Results of the present study indicated that the hormonal contraceptive users in this targeted, high-risk population group had significantly higher level of gingival inflammation than the non-users. This finding is in agreement with a number of earlier studies. For instance, Tilakaratne et al. observed women (n=49 users; n=39 matched non-users) on DMPA for > 2 years and concluded significantly higher levels of gingival inflammation in the DMPA group.7 In another clinical study, Seck-Diallo et al. found that females (n=100) on DMPA had more gingival inflammation, periodontal pocketing, and attachment loss that non-users.8 In 2008 clinical study examining the effect of the levonorgestrel implant on 12 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles periodontium, females (n=47) using progestin implant contraceptives exhibited a statistically significant increase in gingival probing depths compared to non-users9. In 2012, a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Surveys datasets examining DMPA use and periodontal conditions found a positive association.10 Compared with previous studies of this association, the present investigation was the first prospective cohort study with large number of participants to determine the effects of DMPA on gingival health using clinical periodontal parameters that used multiple logistic regression (GEE) modeling. The strength of this study design lies in the ability to identify incident cases of disease as they occur among women using DMPA and those not using hormonal contraceptives. The use of new cases maintained the proper temporal sequence of exposure preceding disease, fulfilling the criterion for detecting a causal relationship. The strength of the chosen type of statistical analysis allowed for the correlation of outcomes within an observation unit to be estimated and taken into account when estimating the regression coefficients and their robust standard errors. Although the logistic model examining the association of DMPA use with the incidence of gingival inflammation demonstrated positive association, Eke et al. reported that partial-mouth periodontal examinations used in this study could produce an underestimation of the incidence of gingival disease. 11 CONCLUSIONS This study provided an increased understanding of the effects of hormonal therapy on the oral cavity and served as a launching point for the research team to make an oral-systemic health connection between hormonal therapy and periodontal diseases, generating critical patientoriented, translational data. 13 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles REFERENCES 1. Kaunitz AM. The role of hormonal contraceptives: long-acting injectable contraception with Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994; 170: 1543-1549. 2. Vittek J, Hernandez MR, Wenk EJ, Rappaport SC, Southren AL. Specific estrogen receptors in human gingiva. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1982; 54: 608-612. 3. Lindhe J, Sonesson B. The Effect of sex Hormones on inflammation. I. The Effect of Progestogen. J Periodont Res 1966; 1: 212-217. 4. Tilakaratne A, Soory M. Androgen metabolist in response to oestradiol -17beta and progesterone in human gingival fibroblasts (HGF) in culture. J Clin Periodontol 1999; 26: 723-731. 5. Tilakaratne A, Soory M. Modulation of androgen metabolism by estradiol-17beta and progesterone, alone and in combination, in human gingival fibroblasts in culture. J Periodontol 1999; 70: 1017-1025. 6. Kent County Health Department. Kent County Health Department Operational Goals [Internet]. Grand Rapids (MI) : AccessKent; ©2001-2012 [cited 2013 Jan 1]. Available from: http://www.accesskent.com/Health/HealthDepartment/. 7. Tilakaratne A, Soory M, Ranasinghe AW, Corea SM, Ekanayake SL, de Silva M. Effects of hormonal contraceptives on periodontium, in a population of rural Sri-Lankan women. J Clin Periodontol 2000; 27: 753-757. 8. Seck-Diallo A, Cisse ML, Benoist HM, et al. Periodontal status in a sample of Senegalese women using hormonal contraception (in French). Odontostomatol Trop 2008; 31: 36-42. 9. Kazerooni T, Ghaffarpasand F, Rastegar N, Kazerooni Y. Effect of levonorgestrel implants on periodontium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008; 103: 255-256. 14 J Periodontol March 2013 Veronika Stiles 10. Taichman SL, Sohn W, Kolenic G, Sowers MF. Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate use and periodontal health in 15-to 44-year-old US females. J Periodontol 2012; 83 (8): 1008-1017. 11. Eke PI, Thornson-Evans GO, Wei L, Borgnakke WS, Dye BA. Accuracy of NHANES periodontal examination protocols. J Dent Res 2010; 89: 1208-1213. 15