Topics in the Psychology of Risk

advertisement

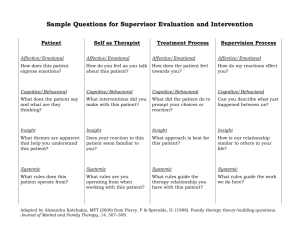

Topics in the Psychology of Risk Thomas S. Wallsten Department of Psychology University of Maryland SAMSI 2007-08 Program on Risk Analysis, Extreme Events, and Decision Theory Outline • Distinguish “risk” in psychology from other domains • Within psychology, distinguish risk – Perception – Communication ─ Attitude ─ Learning • Early approach: EV and a 1-dimension scale of riskiness • A lesson from animal behavior – Coefficient of variation as an index of risk • Revealed risk-benefit trade-offs • Psychometric approaches Outline (Cont’d) • Cognitive and affective components of risk judgment – Lessons from cognitive neuroscience • The role of learning in judging risk • Risk communication • Concluding comments • (Will not cover individual-differences or contextspecific aspects of risk) The Construct of Risk Outside Psychology • Within rational choice (EU) theory – The utility function captures risk attitude • Concave, linear, convex utility functions represent risk aversion, neutrality, attraction, respectively • E.g., Risk aversion ≡ prefer a sure $s to a lottery ($x, p, 0) with EV = $s • Other constructs within economics, engineering, finance, risk analysis – Risk versus uncertainty (Knight, 1921) • Risk ≡ known (aleatory) probability • Uncertainty ≡ imprecise (epistemic) probability The Construct of Risk Outside Psychology • Within economics, engineering, finance, risk analysis (cont’d) – Probability of loss, undesirable outcome – Variability or volatility of outcomes – Index that combines probability and magnitude of loss • Most recently, DHS color-coded Security Advisory System – The higher the Threat Condition, the greater the risk of a terrorist attack. Risk includes both the probability of an attack occurring and its potential gravity. The Construct of Risk Within Psychology • Distinguish risk – Perception – Communication ─ Preference (attitude) ─ Learning with experience • Risk perception and preference – – – – Vary across individuals, situations, cultures Are multidimensional Have emotional and cognitive components Change with experience and learning • Risk communication – Occurs in many formats – Serves purposes beyond communicating risk • We will sample within each of these areas An Early Approach • Due to Clyde Coombs • Portfolio theory – “… risky options involving monetary outcomes with explicit probabilities are evaluated in terms of their expected value and their riskiness and, in particular, that an individual has a single-peaked preference function over risk if expected value is held constant.” (Coombs, Donnell, & Kirk, 1978; p. 497) – Risk is undefined, but increases with probability and with amount to lose An Early Approach • Portfolio theory – Riskiness is undefined • Assumed to vary, at least, with probability and magnitude of loss – Distinguishes • Perception – monotonic function of risk • Preference – single-peaked over risk – Tested • Ss chose or rejected multiple-outcome lotteries among equal EV sets at various EV levels – Supported to a first approximation • But systematic patterns of violations – Not easily generalized to non-numerical contexts A Lesson from Animal Behavior • Energy budget rule for bird, insect foraging – Risk-prone if short-term prospect of starving – Risk-averse otherwise • Shafir (2000) suggests coefficient of variation as the index of risk – CV = SD/EV – Fits with Weber’s Law in psychophysics • Magnitude of a just-noticeable-difference is proportional to the size of the stimulus A Lesson from Animal Behavior Figure 1 from Shafir (2000) summarizing a meta-analysis of studies for which budget rule predicts risk-aversion (circles) or riskproneness (squares) Figure 4 from Shafir (2000) showing risksensitivity of bees and wasps to variability in nectar volume as a function of CV, SD, Var Coefficient of Variation Applied to Human Risk Preferences • Weber, Shafir, & Blais (2004) metaanalysis of 20 studies with humans – CV significantly predicted risky choice • For both gain and loss situations • CV predicted less well in financial than in other domains; variance predicted better • But other factors also were significant; e.g., • Real versus hypothetical outcomes • Nationality – Difference from non-human data may be in how uncertainty was represented and learned Learning via Experience versus Description • All studies in meta-analysis represented alternatives numerically or symbolically • Compared choices under both learning methods – Hertwig, Barron, Weber, & Erev (2004), Weber et al. (2004) – Data supported the idea that CV predicted choices better given learning via experience than description – Authors suggest that associative (rather than rule-based) learning may be operating more strongly in that case – Suggest that deviations of human choice behavior from prescriptive models in finance and economics may be due to people responding to a different risk index than assumed by EU-type models. (Weber et al., 2004, p. 443) Revealed Risk-Benefit Tradeoff • Use historical and population data to estimate risk-benefit trade-offs people make – Starr (1969) did this for voluntary and involuntary activities – Note in both cases R ≈ B3 • Risk measure – fatalities/personhour of exposure • Benefit measure – dollars devoted to activity (voluntary) or contribution of activity to person’s income (involuntary) Revealed Risk-Benefits Tradeoff • Population participation increases as risk decreases over time (Starr, 1969) Psychometric Approach • Pioneered by Slovic, Fischhoff, Lichtenstein • Developed an alternative to Starr’s revealed preferences method • • • • Fischhoff, Slovic, Lichtenstein, Read, & Combs (1978) Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein (1980) Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein (1985) Slovic (1987) Psychometric Approach • Used questionnaire approach – Asked about 30 or 90 hazards • E.g., Home gas furnaces, nuclear weapons, pesticides, aspirin, hunting, jogging, smoking, … • Included the 8 Starr used – Rated • • • • Total benefit to society Risk of dying Acceptability of current risk level 9 or 13 characteristics of risk – E.g., voluntariness, immediacy, known to exposed person, known to science, severity of consequences, … Psychometric Approach • Different risk-benefit relationship than Starr (1969) found – Different underlying assumptions – Different metrics – Different types of data Fischhoff et al., 1978 Psychometric Approach • From Slovic et al. (1980) • Factor analyze the rating scales – Factor 1: Dread, controllability – Factor 2: Known, observable – Factor 3 (not plotted): Degree of exposure • Desire for regulation increases from bottom left to upper right (Slovic, 1987) Cognitive and Affective Components of Risk Judgments • Risk judgments, choices, have affective as well as cognitive determinants – This is consistent with the preceding results – Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch (2001) • Contrast purely cognitive to cognitive plus affective Cognitive and Affective Components of Risk Judgments • Neurological data suggests two systems – Damasio (e.g., 1994) summarizes observations and data: • Prefrontal lobe lesions impair decision making by blocking access to somatic reactions • Little cognitive deficit • Inability to associate choices with adverse consequences • “Somatic marker hypothesis” – Imaging studies show differential activity in frontal lobes (“executive”) and amygdala (emotion, affect) • Others (e.g., Sloman, 1996) suggest – Cognitive component is rule-based – Affective component is associative based Learning in Sequential Risky Choice • Respondents work at a computer-based sequential risky choice task – Wallsten, Pleskac, & Lejuez (2005); Pleskac (2007) – Pump up a balloon to earn money – Keep money if they stop before balloon explodes; otherwise lose it – They learn about the stochastic environment with experience – We successfully model the dynamic learning and sequential choice behavior at level of individual respondents Learning in Sequential in Risky Choice • Cognitive model has three components – Probability learning • DM has a mental model of environment; updates probability estimates in optimal Bayesian fashion – Prospect-theory valuation module – Stochastic choice mechanism based on valuation • Successfully model details of the behavior • Beginning research to manipulate and model affective components Communicating Risk • A vast literature on this topic – Numerical vs. verbal vs. graphical vs. color – Relative vs. absolute risk – Specialized for different domains – e.g. • Medical, environmental, security • Briefly discuss verbal communication – People tend to prefer communicating risk to others verbally and receiving it numerically • Numerous reasons for this preference pattern • Wallsten, Budescu, Zwick, & Kemp (1993) Communicating Risk Verbally range of individual upper bound estimates range from upper to lower median estimate From Morgan (2004) adapted from Wallsten et al. (1986) Almost certain Qualitative description of uncertainty used range of individual lower bound estimates Probable Likely Good chance Possible Tossup Unlikely Improbable Doubtful Almost impossible 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 Probability that subjects associated with the qualitative description 0.0 Communicating Risk Verbally • A new scaling method (Dhami & Wallsten (2005) – Represent phrase meanings in terms of 2ndorder probability distributions (probability signatures) • Resulting representations – Are directly comparable across individuals – Have a natural error theory – Provide, via a model, for predicting binary choices Probability Signatures • Method – Judges select and rank their lexicons – Associate phrases with probabilities, p • Estimating the signatures – Fit normal distributions to ln[p/(1-p)] – Equal-variance normal dist’s provide excellent fits – Equivalent across judges at equal ranks Return Dhami & Wallsten (2005) Probability Signatures • Probability signatures lend themselves to stochastic modeling – That assures a natural error theory when assessing validity – Successfully predict pair-comparison choices • They also provide a metric for interpersonal comparisons of meaning – A consequence of two related conditions • Common unit for all judges • Scaling is unique (no permissible transformation) proportion of correct choices observed proportion 1 0.8 7 for whom model failed 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 Wallsten & Jang (2007) 0.2 0.4 0.6 theoretical proportion 0.8 1 Concluding Comments • Many aspects to the psychology of risk • Various methods needed to study risk judgments – Choice, valuation, questionnaire • Determinants of risk – CV is a useful index when probabilities and outcomes are learned purely via experience – In other cases, there seems to be no simple risk index • Risk judgments are multidimensional • Include affective as well as cognitive components Concluding Comments • The presence of affective components presents a challenge for modeling risk • Effective risk communication is increasingly important and should be informed by our understanding of the psychology of risk References • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Coombs, Donnell, & Kirk (1978) Dhami & Wallsten (2005) Fischhoff, Slovic, Lichtenstein, Read, & Combs (1978) Hertwig, Barron, Weber, & Erev (2004) Knight (1921) Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch (2001) Pleskac (2007) Shafir, S. (2000) Slovic (1987) Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein (1980) Slovic, Fischhoff, & Lichtenstein (1985) Wallsten, Budescu, Zwick, Rapoport, & Forsyth (1986) Wallsten, Budescu, Zwick, & Kemp (1993) Weber, Shafir, & Blais (2004)