Interim Appellate Brief

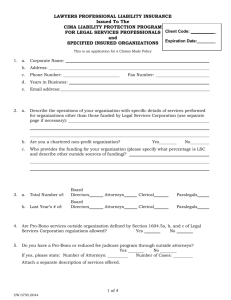

advertisement

PLAINTIFF-RESPONDENT’S RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT-PETITIONER’S PETITION FOR LEAVE TO FILE INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL PURSUANT TO 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) Plaintiff-respondent William Feickert (hereainfter “Mr. Feickert”) hereby submits his response to defendant-petitioner BNSF Railway Company’s Petition for Leave to File an Interlocutory Appeal of the District Court’s Order denying its motion for reconsideration, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b). Specifically, on July 31, 2013, the District Court denied defendant-petitioner’s motion for reconsideration of the District Court’s earlier denial of its motion for summary judgment. Docket No. 53. In its Order, the District Court granted defendant-petitioner’s request for certification to appeal pursuant to § 1292(b). As will be demonstrated, infra, the District Court’s certification was in error, and this Court lacks jurisdiction to review the challenged Order. I. INTRODUCTION This is an ordinary employment discrimination case arising under the ADEA and its state law analogue, that defendant-petitioner has belatedly sought to recast as a collective bargaining dispute. Specifically, two years into this litigation, with discovery completed and summary judgment briefed and decided, defendantpetitioner moved for dismissal1 on the grounds that Mr. Feickert’s discrimination claim was preempted by the Railway Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. §§ 151, et seq. The district court, in a well-considered opinion, denied the motion. However with little Defendant styled its motion as one for reconsideration of the order denying summary judgment; however, as the District Court recognized, in reality its motion was a second motion for summary judgment based on lack of jurisdiction under the RLA. Docket No. 53, p. 7. 1 explanation, the district court granted defendant-petitioner’s request to certify its order for appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b). The District Court’s certification was in error. The statutory criteria for appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) are not met. Consequently this Court lacks jurisdiction to review this matter. Defendant-petitioner’s petitioner must, therefore, be denied. II. RELEVANT FACTS The following facts may be gleaned from the evidentiary record. Mr. Feickert was employed by BNSF Railway Company from October, 1970, until his involuntary retirement in July of 2010. In 1976 he completed training to become a locomotive engineer. He was a member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (“BLET”) union. Docket No. 53, p. 1. Between 1986 and early 2010, Feickert worked as an engineer on the freight line out of Minot, North Dakota. This position entailed working odd hours and weekends. By the 2000’s, Feickert began to desire a position with regular daytime hours and weekends off. By 2009 he had accrued sufficient seniority to successfully bid on such positions. Id. at p. 2. Mr. Feickert learned that the engineer position based in Williston, North Dakota, commonly referred to as the “Williston local”, offered the regular schedule he desired. Although it was far from his home, Mr. Feickert was also aware – in fact it was common knowledge – that BNSF permitted the Williston local (and other staff) to lodge during the work-week in company-paid hotel rooms in Williston. Williston is what defendant denotes an “outlying” location, and many of the BNSF employees working there reside in cities significant distances away. In light of its far-flung locale and the logistical difficulties this posed for its employees, defendant, as a courtesy, allowed Williston-based crew to occupy company-paid hotel rooms2 during the workweek to save them onerous commutes. Docket No. 53, p. 2; Docket No. 29-A-4, 8, 9, 10, 11. For purposes of this appeal, it is important to underscore that employees who voluntarily accepted positions in Williston were not contractually entitled to paid lodging. Petition at pp. 5, 8. Mr. Feickert has never disputed this. According to defendant-petitioner, two categories of employees – neither of which is pertinent here – are contractually entitled to paid lodging. As defendantpetitioner describes it: [E]mployees would be paid for lodging only in two circumstances: 1) when an individual in pool service is required to stay away from his home terminal overnight3; and 2) when BNSF, due to business demands and associated manpower requirements, requires – or “force assigns” train, yard and engine service employees to work at away from home terminals for an extended Defendant reserved between 7-10 hotel rooms in Williston on a daily basis yearround for use by its employees. Docket No. 32-A, B. These were called “guaranteed rooms.” Docket 29-A-8. While, according to defendant-petitioner, these rooms were intended for use by “force assigned” and/or “extra board” employees only, the record discloses that BNSF routinely permitted employees outside these categories to occupy these rooms. Docket No. 29-4, 8, 9, 10, 11. 3 Such employees are referred to as “extra board” employees. Extra board employees are those who volunteer to fill in for an absent employee for a period of up to six days. Docket No. 29-A-5(b), pp. 63-64. 2 period of time. BNSF does not, however, have any agreement with the BLET4 that requires the provision of lodging at outlying points where an employee bids, or voluntarily transfers, to a position. Docket No. 29, p. 3. Deposition testimony from the relevant management officials, Williston trainmaster Larry Berg, and Superintendent of Operations Stephen Reinke, confirms that, at all relevant times, the foregoing was their understanding of the extent of any contractual right to paid lodging. According to these officials, Williston-based employees who were neither “extra board” nor “force assigned” had no CBA right to paid lodging, regardless of whether their position was considered permanent or temporary5. Docket No. 29-A-5, 8. Importantly, notwithstanding the limits of the CBA, defendant-petitioner acknowledges that “regardless of whether a particular train crew member was contractually entitled to paid housing benefits, if there were hotels rooms that BNSF had already paid for and would otherwise go unused, [Trainmaster Berg] would allow train-crew members to occupy those unused rooms.”6 Docket No. 29, p. 4. And indeed the record is replete with examples BNSF permitting Williston-based crew to occupy paid lodging to which they were not contractually entitled. Docket No. 29, A-4, A-5(a), 8, 9, 10, 11; Docket No. 32-A, B. According to defendant-petitioner, this policy “applied to all home-terminaled employees across the BNSF system” whether they were in the BLET, or another union such as the UTU. Petition at 6. 5 Temporary vacancies are described by BNSF as those that last longer than “5 or 6 days.” Such vacancies get bid on, and are no longer considered “extra board” and there is no contractual obligation to provide lodging in those instances. Docket No. 29, A-5(b), pp. 63-65. 6 Indeed prior to taking the engineer position in Williston, Feickert received assurances from Trainmaster Berg that the incumbent would have access to paid lodging. Docket No. 29-A-2, p. 43; A-4, p. 45. 4 It is this extra-contractual, discretionary benefit/privilege that Feickert contends was wrongfully withheld from him on the basis of age. Feickert submitted his bid for the Williston engineer position in or about May 2010. Also bidding on this position was its then-incumbent, Dusty Jurgens. Jurgens lived in Bismark, but had worked in Williston since 2008. In that period he occupied company-paid lodging five nights a week. Docket No. 29-A-2, p. 43; A-8, pp. 18-21; A-10, pp. 20-21, 24-25. Jurgens is substantially younger than Feickert. Docket No. 39, p. 12. After both candidates had submitted their bids, Superintendent Reinke sent a message to Feickert through his union steward. The message was this: if he accepted the position in Williston, he would not be permitted to use paid lodging. Docket No. 29-A-2, p. 43. Reinke never sent this message to Feickert’s younger competitor, Jurgens. Docket No. 29-A-10, pp. 22-23. Because he had greater seniority than Jurgens, Feickert was able to “bump” Jurgens and assume the position. Docket No. 29-A-10, p. 21. Despite Reinke’s order, Mr. Feickert accepted the position in Williston. Docket 29-A-2, pp. 62-63. After his arrival, the company continued to maintain between seven and ten hotel rooms in Williston every weeknight. Docket No. 32-B. Denied access to these accommodations, and unable to find alternative affordable housing due to its scarcity following the Bakken oil boom, Mr. Feickert was forced to live out of his pick-up truck. Docket 29-A-2, p. 45. While he spent his nights in his truck, numerous guaranteed rooms sat vacant only yards away. Docket Nos. 32-A, B; 29-A-2, p. 64; A-11, p. 23. Upset at his treatment, Mr. Feickert lodged an oral grievance with his union. Docket 29-A-2, p. 53. Mr. Berg7, learning of the grievance, contacted Reinke. Docket No. 29-A-5(b), pp. 46-47. Reinke, however, was intransigent and refused to grant Feickert access to the rooms. Id. at p. 48. In July, 2010, Mr. Feickert took a two week prescheduled vacation. Docket No. 29-A-2, p. 55. During this time, Robert Amsler – an engineer 24 years Feickert’s junior -- bid to work the temporary vacancy left by Mr. Feickert. Id., p. 66; 29-A-11, pp. 20-22. According to defendant-petitioner, this temporary position was neither “extra board”, since it exceeded six days, nor a “forced assignment”, since Amsler voluntarily bid on it. Docket No. 29-A-11, p. 22; 29-A-5(b), pp. 63-64. Thus, according to defendant-petitioner’s own interpretation of the CBA, Amsler was not entitled to paid lodging. Docket No. A-5(b), pp. 63-648. Nonetheless, upon arriving in Williston – and taking over Mr. Feickert’s position -- Mr. Amsler was permitted to occupy the very rooms Feickert had been denied. Docket No. A-11, p. 22. In one of many contradictions, Berg denies he was aware that Feickert wanted paid lodging; but Reinke testified that Berg called him about Feickert’s grievances. Reinke testified that he exhorted Berg not to permit Feickert this benefit. Docket No. 29-A-8, pp. 26-27; 29-A-5(b), pp. 46-48. 8 Management Officials Reinke and Schuch testified at deposition that Amsler was not entitled to paid lodging because he voluntarily bid and assumed the temporary vacancy left by Feickert. However, months later, as an attachment to defendantpetitioner’s Reply brief on Summary Judgment, Reinke submitted an affidavit repudiating this damaging deposition testimony. He offered no explanation for this repudiation. The District Court viewed this belated and tactical about-face with a jaundiced eye, correctly noting that post-hoc, contradictory affidavits are not favored. Docket No. 53, p. 11 (citing Camfield Tires, Inc. v. Michelin Tire Corp., 719 F.2d 1361, 1365-66 (8th Cir. 1983); Schiernbeck v. Davis, 143 F.3d 434, 438 (8th Cir. 1998); Nickerson v. Allied Mut. Ins. Co., 198 F.3d 250 (8th Cir. 1999) (unpublished) (an affidavit which contradicts earlier deposition testimony must be disregarded). 7 In late July, 2010, Mr. Feickert could no longer tolerate living out of his car, particularly when younger crewmen were gratuitously provided hotel rooms. He retired, effective July 31, 20109. Docket No. 29-A-2, pp. 56-57. He was 60 years old at the time, and had given BNSF 40 years of service. Docket No. 53, p. 6. Immediately following his departure, Jurgens returned to Williston replace Feickert. He was permitted to stay in company lodging every night of the workweek. Docket No. 29-A-9, p. 24. Not long after Feickert retired, BNSF decided to add a number of new positions in Williston. See Docket No. 53, p. 6. The record reveals that all of the new positions were advertised as eligible for company-paid housing due to the tight housing market in Williston caused by the Bakken oil boom. See Id. All of these positions – as well as other new positions in Williston -- were filled by substantially younger employees. See Docket No. 32-A-3, ¶¶ 3-6. III. PROCEDURAL HISTORY Feickert filed a complaint alleging he was discriminated on the basis of age when he was denied lodging in Williston and ultimately forced to retire. His claims arise under the ADEA and its state law analogue. Docket No. 1. Feickert has never claimed a violation of the CBA. He acknowledges that he was not contractually entitled to paid lodging. Following discovery, which included numerous depositions, defendant moved for summary judgment pursuant to F.R.C.P. 56. Docket No. 29. At that time, it did not argue that Feickert’s claim was preempted under the Railway Labor Act. Because the engineer position in Williston had a one-year “tie down”, Feickert was precluded from transferring to another position. Docket No. 53, p. 2. 9 Id. Rather it argued that the evidence did not support a prima facie case of age discrimination, and that BNSF had legitimate nondiscriminatory reasons for denying Feickert paid lodging. Feickert opposed the motion and adduced evidence demonstrating that Feickert was the only employee in Williston that had ever been denied paid housing, and that he was also the oldest. Docket No. 32. It also underscored numerous instances where Reinke and Berg had provided shifting and inconsistent testimony, a pattern suggesting mendacity and pretext. Id. In its Reply brief, BNSF argued, for the first time, that Feickert’s complaint was preempted by the Railway Labor Act. 45 U.S.C. §§ 151-188. Docket No. 35. It argued that Feickert’s claims boiled down to a breach of contract claim under the CBA, and thus constituted a “minor dispute”, subject to the RLA’s exclusive arbitral process. Id. The District Court rejected BNSF’s arguments. It observed that Feickert’s claims were not grounded in the CBA, but arose from independent statutory sources prohibiting age discrimination in employment. It noted that the resolution of the case turned on Reinke and Berg’s motives for denying Feickert paid lodging, and not on an interpretation of the CBA. Docket No. 39. BNSF, dissatisfied with this outcome, filed a motion for reconsideration, wherein it pressed its preemption argument. Docket No. 46. The Court once again denied defendant’s motion, again reiterating that Feickert’s claims arose from independent statutory sources and did not require an interpretation of the CBA for resolution. Nonetheless, despite its well-supported findings based on well-settled authority, the District Court certified the matter for interlocutory appeal. IV. INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL STANDARD NOT MET The defendant-petitioner seeks appellate review of the district court’s order pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b). That statute permits interlocutory appeals of district court orders where the following criteria are satisfied: 1) the order involves a controlling question of law; 2) there is substantial ground for difference of opinion; and 3) certification will materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation. 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b); Union Cnty., Iowa v. Piper Jaffray & Co., 525 F.3d 643, 646 (8th Cir. 2008) (quoting White v. Nix, 43 F.3d 374, 377 (8th Cir. 1994)). The requirements of § 1292(b) are jurisdictional. White, 43 F.3d at 376. Thus if they are not met this Court cannot accept this appeal. Id. In evaluating whether to accept this appeal, this Court must be mindful that § 1292(b) constitutes a limited exception to the long-established “final judgment” rule and related policy against piecemeal appeals in federal appellate practice. See Andrews v. United States, 373 U.S. 334, 340 (1963) (recognizing that “[T]he longestablished rule against piecemeal appeals in federal cases and the overriding policy considerations upon which that rule is founded have been repeatedly emphasized by this Court.”) The 8th Circuit has cautioned that § 1292(b) review should be “granted sparingly and with discrimination,” White, 43 F.3d at 376, and is reserved for “extraordinary cases where the decision of an interlocutory appeal might avoid protracted and expensive litigation,” Union County, 525 F.3d at 646. It was “not intended merely to provide review of difficult rulings in hard cases.” Union County, 525 F.3d at 646. Defendant-petitioner has not met its heavy burden of demonstrating that this case is an exceptional one meriting interlocutory review. See White v. Nix, 43 F.3d at 376 (petitioner seeking § 1292(b) review “bears the heavy burden of demonstrating that the case is an exceptional one in which immediate appeal is warranted.”) Specifically, although the issue of preemption under the RLA does constitute a controlling question of law, the standard for preemption is well-settled and not the source of conflict or substantial disagreement. Further, granting interlocutory appeal will not materially advance this litigation, but will delay it further. A. ORDER DOES NOT INVOLVE A CONTROLLING QUESTION OF LAW ABOUT WHICH THERE IS SUBSTANTIAL GROUND FOR DIFFERENCE OF OPINION With regard to the § 1292(b) requirement that a challenged Order involve a controlling question of law about which there is substantial ground for difference of opinion, the District Court made the following dispositive observation: “[T]here is a substantial body of law dealing with RLA preemption…The law seems to be well-established.” Docket No. 53, p. 12. Nonetheless the District Court went on to opine that § 1292(b) review was appropriate because “the application of the law is not a simple matter, and there is a substantial ground for a difference of opinion.” Id. The foregoing demonstrates a fundamental misconception on the part of the District Court regarding the meaning of § 1292(b)’s second criterion. Specifically, the phrase “substantial ground for difference of opinion” refers to the controlling law itself, not its application to a particular set of facts. White v. Nix, 43 F.3d 374, 378 fn. 3 (there is not “substantial ground for difference of opinion” where the controlling law is “relatively well settled” and defendant merely takes issue with the court’s application of the law to a particular factual scenario); Union County v. Piper Jaffray & Co., Inc., 525 F.3d 643, 647 (where legal issue was neither novel nor the subject of widely conflicting opinion, second criterion for interlocutory appeal under 1292(b) not met); Kuhr v. Millard Public School District, 2012 WL 10387, * 2, (D.Neb.) (unpublished) (where “the 8th Circuit has spoken on the issue at hand” – specifically holding that right to nominal damages for First Amendment violation is enough to confer jurisdiction and avoid dismissal for mootness – the law is clear, and there is no substantial basis for difference of opinion); McFarlin v. Conseco Services, LLC., 381 F.3d 1251, 1259 (2004) (“in determining whether to grant review, we should ask if there is substantial dispute about the correctness of any pure law premises the district court actually applied”; where there is no disagreement about what the law is, but rather disagreement over the correctness of the district court’s application of it to a particular factual scenario, the second 1292(b) criterion is not met); United Air Lines, Inc. v. Gregory, 716 F.Supp.2d 79, 92 (D.Mass.2010) (noting that substantial ground for difference of opinion exists when “issue involves one or more difficult and pivotal questions of law not settled by controlling authority”, and concluding that since ADA preemption standard wellsettled in the Circuit, this criteria not met). Whether the District Court appropriately applied settled-law to particular facts is not a proper question for interlocutory review. That the RLA preemption standard is well-settled can scarcely be gainsaid. The District Court in fact provided the following cogent and thorough description of this standard: BNSF contends that Feickert’s claim of age discrimination is a minor dispute subject to mandatory arbitration before the RLA adjustment board. A cause of action is a minor dispute if it involves the interpretation of an existing labor agreement and can be conclusively resolved by doing so10. Hawaiian Airlines Inc. v. Norris, 512 U.S. 246 at 256 (1994). In this context, interpretation means the resolution of a dispute over the meaning of a provision of a labor agreement. Sturge v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 658 F.3d 832, 838 (8th Cir. 2011). The RLA does not preempt a cause of action to enforce rights that are independent of a collective bargaining agreement. Norris, 512 U.S. at 256. When the meaning of the contract terms are not disputed, the mere fact that a collective bargaining agreement is consulted or referenced in the course of litigation does not necessarily mean the cause of action is preempted. Evermann v. BNSF Ry. Co., 608 F.3d 364, 366-67 (8th Cir. 2010). Docket No. 53, p. 8. Applying the foregoing principles to the facts of this case, the District Court properly held that Feickert’s claim was not a minor dispute Defendant once again argues that this matter concerns a minor dispute because Feickert’s treatment was “arguably justified” by an interpretation of the CBA. Its argument is conceptually flawed. The “arguably justified” standard is employed to police the line between major and minor disputes. “This test sa[ys] nothing about the threshold question whether the dispute was subject to the RLA in the first place.” Norris, 512 U.S. at 266. See Taggart v. TWA, Inc., 40 F.3d 269, 274 (“Under Norris, the ‘same factual inquiry’ and the ‘arguably justified’ tests are no longer grounds for pre-emption”). 10 preempted by the RLA. It observed that the claim arises independently of the CBA, that it cannot be conclusively resolved through an interpretation of the CBA, and that its resolution requires an examination of Reinke and Berg’s “motives and intentions in denying housing to the oldest engineer assigned to Williston while providing housing to every other engineer who worked out of Williston…”. Docket No. 53, p. 9-12. See Norris, 512 U.S. at 261 (“purely factual questions…about an employer’s conduct and motives do not require a court to interpret any term of a collective-bargaining agreement.”) (citation omitted) (internal quotations and ellipses omitted). The District Court’s analysis was thorough, sound, and consistent with numerous opinions out of this Circuit applying the RLA preemption test in similar situations. See, e.g., Sturge, 658 F.3d 832 (ERISA claim for retaliatory discharge not preempted by RLA; claim was independent of CBA and turned on employer’s motives in taking adverse action); Pittari v. Am. Eagle Airlines, 468 F.3d 1056, 1060 (8th Cir. 2006) (ADA claim not preempted by RLA, as it arose independent of rights under CBA); Deneen v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 132 F.3d 431, 439 (8th Cir. 1998) (Pregnancy Discrimination Act claim arose independent of CBA and not preempted by RLA); Benson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 62 F.3d 1108, 1115 (8th Cir. 1995) (ADA claim not preempted); Taggert v. Trans World Airlines, Inc., 40 F.3d 269, 274 (8th Cir. 1994) (state law not preempted); Norman v. Mo. Pac. R.R., 414 F.2d 73, 83 (8th Cir. 1969) (Title VII); Gilmore v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 504 F.Supp.2d 649 (D.Minn.2009) (FMLA); Ludwig v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 98 F.Supp.2d 1057, 1068-69 (D.Minn.2000) (Title VII); Cavanaugh v. Burlington Northern R.R. Co., 941 F.Supp. 872 (D.Minn.1996); Stevens v. Braniff Airways, Inc., 490 F.Supp. 231, 233 (D.Minn.1980) (Title VII). Despite the foregoing, the District Court lamented that application of the RLA standard to the facts of this case was difficult. Defendant-petitioner agrees, and claims that this difficulty justifies § 1292(b) review. However, as already explained, § 1292(b) was “not intended merely to provide review of difficult rulings in hard cases.” Union County, 525 F.3d at 646 (citation omitted). Because the applicable controlling law is “well-established”, the second criterion for 1292(b) review is not met. C.f. United Air Lines, Inc. v. Gregory, 716 F.Supp.2d 79, 92 (D.Mass.2010) (no substantial ground for difference of opinion exists where ADA preemption standard well-settled in the Circuit, and defendant simply disputes its application to the facts). See Conseco, 381 F.3d at 1259 (“[T]he antithesis of a proper 1292(b) appeal is one that turns on whether there is a genuine issue of fact, or whether the district court properly applied settled law to the facts or evidence of a particular case”). B. INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL WILL NOT MATERIALLY ADVANCE THE ULTIMATE TERMINATION OF THIS LITIGATION The third criterion for exercising jurisdiction over this appeal requires a finding that interlocutory review may materially advance the ultimate termination of this litigation. This criterion reflects the intention of § 1292(b) framers to permit appeal where doing so would “avoid protracted and expensive litigation.” See Union County, 525 F.3d at 646 (citation and ellipses omitted). In this case the petitioner waited until 22 months of litigation had elapsed before asserting its preemption argument. In the interim, discovery, including numerous depositions, has been conducted and closed; the parties have briefed -- and the Court has decided -- whether to grant summary judgment, and the matter stands poised and ready for trial. Trial will likely last a few days time. At this juncture an appeal will not materially advance the termination of this litigation. Nor will it serve to “avoid protracted litigation.” Rather, it will serve to delay a case that is ready for trial. The District Court found as much when it concluded that “an interlocutory appeal would not unduly delay the litigation…”. Docket No. 53, p. 13 (emphasis added). Obviously that is not the correct standard, and District Court’s conclusion actually demonstrates that the last criterion is not met. See, also, 16 Fed.Prac. & Proc. Juris. § 3930 (2d.Ed.), Jurisdiction of the Courts of Appeals, Interlocutory Review (“If a trial can be had in a few days, the possibility of saving relatively small amounts of trial court time is not thought sufficient to justify immediate appeal.”). See, e.g., Kraus v. Board of County Road Comm’rs for Kent County, 364 F.2d 919, 922 (6th Cir. 1966) (“Section 1292(b) was not intended to authorize interlocutory appeals in ordinary suits for personal injuries or wrongful death that can be tried and disposed of on their merits in a few days.”) Another reason why this appeal would not materially advance the termination of this litigation is that it is quite unlikely that it would result in reversal. Controlling authority supports the District Court’s well-considered conclusion that this case is not preempted by the RLA. The recent case of Sturge v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 658 F.3d 832 (8th Cir. 2011), is especially analogous. In that case an airline employee was terminated ostensibly for using marijuana. He argued that the termination was in fact in retaliation for his application for disability benefits. He conceded that marijuana use was “just cause” for termination under the CBA, but that it was not the real reason for his dismissal, pointing out that another employee who had used illegal substances was not terminated. The Airline argued that the matter was preempted since it would require interpretation of the “just cause” provisions of the CBA, as well as interpretation of terms relating to whether the comparator was similarly situated. The Court rejected these arguments. It noted that Sturge did not dispute any provisions of the CBA, nor dispute that his infraction constituted “just cause” under its terms; rather, he simply claimed his termination was motivated by a desire to retaliate for his exercise of ERISA rights. Thus, the Court concluded, the claim “requires not an interpretation of a collectively bargained agreement, but a resolution of a “purely factual question about an employee’s conduct and motives.”” Id. at 838 (citing Norris, 512 U.S. at 261) (internal quotations and ellipses omitted). Further, Sturge did not dispute the CBA terms relating to whether his comparator was similarly situated. Thus the Court concluded that at most CBA would merely be consulted, and not “interpreted.” Id. This case is materially indistinguishable from Sturge in that Mr. Feickert does not dispute the meaning of the CBA, nor dispute that he was not contractually entitled to paid lodging. He simply claims this benefit was denied him for improper purpose. Further he does not dispute any CBA terms as they may relate to his comparators’ status. Defendant-petitioner, for its part, does not claim the CBA is a basis for any differential treatment comparators, since none were “force assigned” nor extra board at the time they received paid lodging. Thus, just like in Sturge, at most the CBA may be consulted, but it will not have to be interpreted. Because reversal of the District Court’s well-considered opinion and Order is unlikely at best, this appeal will not materially advance the termination of this litigation. Thus, once again, the prerequisites for § 1292(b) interlocutory review are not met. V. CONCLUSION As the criteria for interlocutory appeal are not met, this Court does not have the requisite jurisdiction to review the District Court’s Order. Defendantpetitioner’s petition must therefore be denied.