sample-conference-abstracts - Georgetown Digital Commons

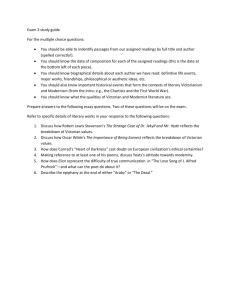

advertisement

SAMPLE CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS ENGLISH 595 | TRAGIC ECOLOGIES The following represent sample successful abstracts from C19 scholars at various stages of their careers – from early to late graduate student, with a few from assistant professors. Together they can be taken as a set of generic coordinates for what good abstracts must do and how they might do them; they are not models, however, and as with any genre the key to writing a superb abstract is to tweak the template carefully and to your own purposes. My endless thanks to my fellow Victorianists Lara Karpenko, Kristin Mahoney, Stefan Waldschmidt, and Anna Gibson. Appropriating In Memoriam in G.H. Lewes’ The Physiology of Common Life For NAVSA Pasadena, Fall 2013, Theme: Evidence Stefan Waldschmidt, Graduate Student, Duke University Recent biopolitical thought is largely concerned itself with the question of how lifein-general gets sorted into various forms of qualified life—bare life, precarious life, surplus life, organic life, spiritual life—and how that sorting process feeds back into our understanding of what “life,” in general, is. This paper will examine how one such process of sorting and feedback works to establish the terms of biopolitical thought between the 1850s and the 1860s, as Victorian thinking attempts to reconcile the seeming contradiction between the ceaselessly productive and destructive, non-teleological character of organic life and the progressive view of life that would see the spirit as moving towards ever-moreperfect forms. In In Memoriam, Tennyson will present the difficulty of this schism by representing these two views of life as only metaphorically linked; for him, the process of mourning will be the process of trying to find metaphors that would transfigure the hostility of organic life into a progressive spiritual afterlife. The affective charge of Tennyson’s In Memorium will conceptualize itself as coming exactly from the tenuousness of those metaphorical connections—links that always threatens to fail and thus must be all the more carefully held. Yet the fragility of Tennyson’s metaphors will also make his lyrics uniquely divisible. When G.H. Lewes will quote Tennyson’s “The babe new to earth and sky” in The Physiology of Common Life, he will be able to use Tennyson as evidence for his own view of a decidedly non-spiritual life-in-general by simply excising those highly divisible parts of Tennyson’s poetry that would have made the metaphorical connection. In as much as Tennyson will be opposing spiritual life to organic life in order to represent the difficulty of wrestling with the reconciliation of non-teleological processes with a concept of progress, so Lewes, coming to Tennyson’s work, will be able to find a readymade version of non-teleological organic life; all that needs to be done is completely sever what was already a tenuous metaphorical connection in order to present Tennyson’s lyrics as evidence for the possibility of conceiving life materialistically. For, in The Physiology of Common Life, there is no life-afterlife opposition: only life and more life, the constant reorganization of organic processes, with anything else being dismissed as the fantasies of an outdated romantic vitalism. What we can learn about mid-Victorian biopolitical thought from this moment of appropriation is how later Victorian physiology found the poetic imagery necessary to render its materialism comprehensible. As Tennyson’s vestigial Romanticism would advance a qualified spiritualism by holding it up against the productive life that continues all around him, so that Romanticism already contains a view of self-sufficient, productive, and wholly organic processes that Lewes’ materialism can present as a new picture of life-in-general. In the Beginning, there was “Zooks”: Browning’s Poetry as Thought in Process Abstract proposal for “Browning’s Beginnings and Endings” panel with Mary Ellis Gibson at the "Robert Browning and Victorian Poetry at 200" Conference in Waco Texas, Spring 2013. Stefan Waldschmidt, Graduate Student, Duke University Many a Browning poem begins with lines that are peppered with ellipses and dashes, stutterings and exclamations—Lippi’s “Zooks” (3), Mr. Sludge’s “Aie—aie—aie!” (16), the Spanish monk’s “Gr-r-r” (1). This paper will ask what it means for Browning’s poetry to begin with these strange noises: what picture of thought-in-the-process-of-working-itself-out is Browning trying to build with such non-signifying stutters? Such noises are not the “Oh” that would signal the beginning of Romantic apostrophe—like Wordsworth’s “O gentle sleep!”— because they are not the prelude for an address to some external transcendental entity. Rather, as this paper will argue, these noises are included to show that the picture of thought his poems present is a picture that is still in its raw form: it has not yet been cleaned up, ordered or edited, it has not been—in Wordsworth’s terms—“recollected in tranquility.” The only picture of thought that is worth capturing for Browning is the spontaneous overflow of emotion as it is in the process of happening. This is because, for Browning, there is an ethics to focusing on thought as it unfolds with all of its excesses and ruptures. Indeed, to have only the completed recollection, as honed by poetic genius, would mean having “The end ere the beginning” (“Parleyings with Christopher Smart” 241). Taking such a shortcut would, for Browning, be an inexcusable weakness of mind: it would be a poetry unsuited for thought because it would circumvent the hard process of working through thought itself. Indeed, the succinct formulation that Browning comes to at the end of “Parleying with Christopher Smart” begins with a characteristically stuttering “It seems as if… or did the actual chance / Startle me and perplex?” (1-2). Thus, for Browning, in order to reach any end, we must begin with the beginning of thought: we must begin with thought that is still in the process of being resolved into language and still strewn with unsignifying excess and peculiar exclamations. Detection and Sensation: Francis Galton, Wilkie Collins, and the Forms of Personal Identity In 1892, Francis Galton culminated his research on personal identification with his systematic study of fingerprints, in which he incorporated remarks by the director of the French Penitentiary Department on the advantages of finger printing “to fix the human personality, to give to each human being an identity, an individuality that can be depended upon with certainty, lasting, unchangeable, always recognisable and easily adduced.” 1 Forensic methods of detection that gained in popularity from the 1870s, including Galton’s own composite photography, are inseparable from the work of detection in “sensation novels.” While purportedly interested in unearthing a hidden truth about individual identity, novelistic detection was primarily engaged in “giving” or “fixing” an identity upon each “human personality.”2 By focusing on narrative attempts to “fix” identity in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White and Armadale and in Galton’s forensics, this paper reads detection as a deductive formal technology for approaching the “human personality” that is always confronted by a set of narrative evasions rooted in a constantlychanging sensory body. In order to show the ways in which “sensation” resists the fixing forms of detection, I explore moments of narrative breakdown in which the body’s sensory (in)capabilities shape the unfolding of a text and represent the self as responsive, unpredictable, and not reducible to the determinative analysis of detection. This paper challenges a tendency in studies of the Victorian novel to treat detection and sensation as either distinct or interchangeable generic forms. Instead, I offer a framework for understanding how these forms develop alongside one another as interdependent and yet contradictory narrative technologies for producing personal identity, for imagining a body characterized both by its representable physical characteristics and by a collection of sensory processes with their own performative and narrative capacities. Anna M. Gibson Department of English, Duke University anna.gibson@duke.edu (Note, Anna is a graduate student - NKH) 1 p. 169. Finger Prints. London: Macmillan, 1892. In drawing together Galton’s forensic technologies and Victorian fiction, I build upon the work of Ronald R. Thomas (Detective Fiction and the Rise of Forensic Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.) 2 “How Valour burns”: Occult Nationalism in the Work of Althea Gyles Kristin Mahoney, Western Washington University Victory! Home! Or life with the great dead! How Valour burns! --Althea Gyles, “The Farm Hand” (1914) In 1898, W.B. Yeats published an essay in The Dome on “A Symbolic Artist and the Coming of a Symbolic Art.” The subject of the piece was an Irish artist, Althea Gyles (1868-1949), a figure, Yeats argued, who represented “a new manner in the arts of the modern world” arising from a circle of “Irish mystics who have taught for some years a religious philosophy which has changed many ordinary people into ecstatics and visionaries.” In Yeats’s eyes, the works of Gyles contained a “visionary beauty,” and the “lithe figures of her art [quivered] with a life half mortal tragedy, half immortal ecstasy.” While her work has now been largely forgotten, she was considered by many to be one of the most interesting illustrators and book designers working at the turn of the century. Oscar Wilde described her as “an artist of great ability,” and Bernard Muddiman, in his Men of the Nineties (1921), referred to her work as the “acme of the period’s realization of the weird.” Gyles designed the cover for Yeats’s The Secret Rose (1897) as well as the 1899 edition of Poems and The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). Her designs, which featured iconography related to Golden Dawn rituals, reflected her growing involvement with Yeats’s brand of Celtic occultism. As her attachment to Yeats intensified, Gyles became one of the most prominent women associated with Order of the Golden Dawn. Aleister Crowley’s short story, “At the Fork of the Roads” (1909) reveals that Gyles also played a key role in the struggle between Yeats and Crowley for control of the Order of the Golden Dawn, operating as a site of masculine competition as the animosity between the two men escalated. Her relationship with Yeats eventually disintegrated as a result of his disapproval of her affair with the publisher and purveyor of pornography, Leonard Smithers, but the impress of her association with Celtic occultism continued to be evident in her later works. In this paper, I will examine Gyles’s illustrations and book covers from the 1890s in relationship to the war poetry she wrote in the years following her involvement with the Order of the Golden Dawn and investigate how the Celtic occultism of the fin de siècle informed Gyles’s enthusiastic representation of heroism and martyrdom. As Richard Kearney has argued, Yeats’s investment in the occult seems to have facilitated his endorsement of Patrick Pearse’s ideology of blood sacrifice. I will consider whether the bellicose energies of Gyles’s war poetry should similarly be understood as an outgrowth of her interest in occult nationalism. While Yeats’s interest in the occult has often dismissed as escapist, as a retreat from the fraught political realities of his nation’s present, recent criticism by, for example, Claire Nally has worked to uncover the complex ties between Yeats’s nationalist politics and his spiritual beliefs. In addition, recent work by, for example, Alex Owen has called for a new attentiveness to the links between occultism and modernity at the fin de siècle. I will similarly work to take seriously the role that occult spirituality played in the processing of national politics and modern events and in turn consider how Yeats’s occult nationalism was transmuted and revised at the hands of Althea Gyles as she responded to escalating national antagonism at the turn of the century. Kristin Mahoney Department of English Western Washington University 516 High Street Bellingham, WA 98225 kristin.mahoney@wwu.edu Old Guard/Avant-Garde: Vernon Lee and the Politics of Aestheticism in the Twentieth Century I take of my hat to the old guard of Victorian cosmopolitan intellectualism, and salute her as the noblest Briton of them all. --George Bernard Shaw, review of Lee’s Satan the Waster (1920) We belong to a generation which has—to be blunt—passed away. --Edmund Gosse to Vernon Lee in 1906 While it might have been much neater and simpler had all the members of the Aesthetic Movement agreed to pass away in 1901, the fact remains that figures like Vernon Lee, Arthur Symons, and Baron Corvo lived long into the twentieth century. Though they incorporated elements of a new aesthetic into their works, they also retained a particularly Victorian form of aestheticism in their approach to social and political concerns. What does it mean then for yesterday’s avant-garde to become understood as an old guard? And what kinds of cultural critique does this temporally marginal position enable? In this essay, I read Gospels of Anarchy (1908), a work Lee referred to as “marginalia, mere puttings into shape of the notes taken, often with a pencil on the poor defaced books themselves, in the course of my readings,” in relationship to the marginalia in her copies of socialist and psychoanalytic texts archived at the British Institute in Florence. Writing in the margins allows Lee to materially foreground what Hilary Fraser has referred to as her “interstitial identity,” her status as a sexual and national outsider. At the dawn of the twentieth century, Lee’s outsiderism is compounded as she becomes the representative of an outmoded Victorian avant-garde that refuses to disappear. From this marginalized position, Lee articulates a critique of aggravated appetites, egoism, and violence, a critique that serves as a foundation for the pacifist stance that she adopts in the years leading up to the war. Writing in the margins of new economic and psychological texts and writing from the margins of the new century, Lee expresses an interrelated set of concerns about the distortion of time and desire in the early-twentieth century. She harps on Marx’s obsession with the future and the significance of the past in Freud’s theories of identity. Her marginal notes foreground the fact that both Freudian and Marxist theories rely upon a bizarre and distorted conception of temporality and that, in both Freud and Marx, the strange way the modern individual experiences time is linked to the way the modern individual wants. This marginalia, which stands outside the development of new and problematic forms of appetite and aggression, serves in turn as the conceptual model for the type of thinking Lee wished to do in Gospels of Anarchy and in the more overtly political and pacifist work that followed, such as The Ballet of the Nations (1915). Lara Karpenko Assistant Professor of English Carroll College 100 N. East Ave Waukesha WI 53186 (262) 524-7257 lkarpenk@cc.edu “Deformities and monstrous aberrations from nature”: Masculinity, Pathology and the Invention of Normality This paper proposes to interrogate the concept of pathology in terms of Victorian constructions of appropriate masculinity. More specifically, I will examine Adolphe Quetelet and Francis Galton's statistical creation of normal masculinity in order to suggest that the concept of pathology is inextricably intertwined with the concept of normality. In the first movement of my paper, I examine Adolphe Quetelet’s A Treatise on Man, (English translation: 1842). Arguably the first statistical study to take the human body as its subject, Treatise seeks to define what Quetelet terms “the average man.” Though Quetelet, to some extent, does use the term “man” in a universal sense, he dedicates almost every graph, every chart and every calculation to measuring and quantifying specifically masculine bodies. As Quetelet equates normality with masculinity he also paradoxically defines the average man as one that represents “the type of perfection” and thus urges men to strive for normality. Widely read and immediately embraced by the Victorian readership, A Treatise on Man’s influence extended far beyond the relatively limited realm of statistics. With this in mind, in the second movement of my paper, I examine Sir Francis Galton’s proto-eugenic composite photographs and argue that composite photography borrows from statistical analysis the impulse to categorize and type masculine bodies on the basis of physical markers. As normality became associated with a very narrow and very specific type of masculinity, the concept of the pathological thus proliferated and the definition of acceptable masculinity became increasingly narrow. Through my analysis of statistics and normativity, I thus reveal a complex social mechanism that profoundly influenced the experience of masculine embodiment during the Victorian era. Lara Karpenko Assistant Professor of English Carroll University 100 N. East Ave Waukesha WI 53186 (262) 524-7257 lkarpenk@carrollu.edu Application for INCS 2011: Speaking Nature 11/1/2010 DEFINING THE NATURAL MAN: ANTI-CONSUMERISM IN GEORGE DU MAURIER’S THE MARTIAN This paper examines the concept of nature in terms of late-Victorian constructions of appropriate or “natural” masculinity. More specifically, through an examination of the George Du Maurier’s final novel, The Martian (1897), this paper will explore the fractious relationship between Victorian popular literature and masculine embodiment. Written in response to the excessive popularity of his second novel, Trilby (1891), The Martian heartily critiques consumer manias and suggests that only natural, healthy, and admirable men can resist the disfiguring effects of consumer culture. Within Du Maurier’s story, the admirable and heartily masculine Barty Josselin, (upon receiving inspiration from a Martian named Martia) writes a series of incredibly popular novels. Though Du Maurier vehemently critiques Barty’s unthinking fans and represents them as deformed, disfigured and unnatural, he nonetheless suggests that Barty’s novels still posses inherent value. The worth of Barty’s literature is guaranteed by his stable, handsome and normalized masculine. By the end of the novel, I suggest that Du Maurier draws on the eugenic work of Francis Galton in order to suggest the society will be improved and vulgar consumerism will be avoided if Barty’s natural masculine body proliferates throughout England. This paper is part of a larger project in which I build on the work of Brent Shannon and David Kuchta and challenge the concept of the “Great Masculine Renunciation” of fashion and popular culture and also complicate a long standing critical tradition that conflates mass consumerism with the feminine. Although The Martian may critique mass consumerism, Du Maurier's very anxiety reveals the degree to which the Victorian public “naturally” connected masculine embodiment and popular culture. Ultimately, I will argue that the masculine body became the site over which Victorians defined, negotiated and understood mass commodity consumption. “Sir Richard Burton,” Orientalist: Empire, Islam, and the Politics of Nonidentity FOR NAVSA 2004 At the heart of Edward Said’s magisterial investigation of Western empire’s Inside/Outside logic sits Richard Francis Burton, the celebrity explorer who for Said and later critics embodies the very “voice of European ambition for rule over the Orient” (Orientalism 196). But the Orientalist found guilty in that paradigm-defining work had a curious -and heretofore unexplored-- relationship to the very logic Said is most interested in critiquing. Burton was born in Ireland, grew up in France, constantly referred to himself as a “gypsy,” and wrote of his family that “we never thoroughly understood English society, nor did society understand us.” He would later achieve the rank of “master” in the radically anti-individualist system of Sufi Islam, a sect whose teachings, for Burton, described a continual ascent through difference that would culminate, he thought, in the complete transcendence of identity itself. The explorer later renounced the very concept of selfhood in a series of public speeches. This context informs my readings of Burton’s more “literary” works, which describe in even greater complexity a similar, similarly surprising theory of non-identity. With close readings of Burton’s most striking meditation on imperial selfhood -and lack of it--, A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al Madinah and Meccah (1864), and with attention to The Kasidah of Haji Abdu El-Yezdi, a long poem on refracted identity Burton composed in 1853, this paper significantly revises current narratives of Burton’s relationship to the epistemological apparatus of British Empire. Seen in this new light, Burton’s movement, in the Pilgrimage, through what he calls “Moslem inner life” need not be viewed simply as the narrative of ‘passing,’ of ‘going native,’ or even of colonial ambivalence it might first appear to be. Likewise the Kasidah: Burton’s weirdly polyvalent, ventriloquized poem on selfhood demonstrates formal complications that are also inscribed, I argue, on Burton as an imperial subject more generally. On close examination, what Burton once called his “queer conviction of divided identity” in fact resolves into a fluid contingency where mere “division” or ambivalence no longer describes the non-identity he narrates. In combining close readings and intensive historical work with current political analyses of power, my paper ends by proposing that Burton’s mid-Victorian refusal of self addresses, proleptically, contemporary theories of non-identity – that radical concept of Adorno’s whose most interesting current interpreters include Hardt & Negri and Agamben. My approach to Burton, however, is not a theoretical one. But by using close literary analysis and a wide array of archival evidence, I suggest that Burton’s acrobatic disavowals of self engage with current debates interested in imagining a way out of, or through, current understandings of the relationship between identity and power. The Burton emerging from my analysis, then, is far from the singleminded apparatchik of empire Said’s and later analyses figure him to be. Rather, the non-subject we meet on close examination of the explorer’s life and works poses important challenges, I think, to existing narratives of Victorian empire. NATHAN K. HENSLEY Duke University Specters of Morgan, or the Critical Afterlives of Imperial Historiography For MLA 2005 This paper evaluates Lewis Henry Morgan’s influence on contemporary critical practice, tracing what his British colleague E.B. Tylor might have called the survivals of Morgan’s powerful nineteenth century progress narrative in early twenty-first century literary criticism. Focusing especially on Ancient Society’s famous three-stage system (savagery, barbarism, civilization), I show that versions of Morgan’s developmental teleology continue to animate knowledge production in its contemporary critical forms, despite the best efforts of recent critiques to decenter such approaches. I ask, further, whether the persistence of this paradigm doesn’t identify an important but undertheorized problem in literary studies: Can we have criticism without progress? My paper begins with a close study of Ancient Society’s narrative structure. Here I extend insights into narrative ethics by Paul Ricoeur and Georg Lukacs by calling attention to the political significance of Ancient Society’s developmental plot. I note that trends in postcolonial studies have objected to the double-violence such progress narratives produce. According to what has become critical common-sense, that is, whether we romanticize the epochs and people consigned to the past, as Morgan himself did, or whether we encourage “progress” to wipe them out more quickly, violence ensues – either “epistemic” (as Spivak calls it), or quite real. Having established what is at stake, politically and ethically, in Morgan’s imperial progress narrative, I show that mediated or obscured forms of his tale underwrite influential theoretical paradigms on the contemporary left. We know that Ancient Society’s three-stage structure, materialist method, and conceptual apparatus underpin Engels’ famous thoughts on family, private property, and the state. My paper briefly outlines that text’s own paradoxes, but focuses in more detail on the contemporary uses to which Morgan, via Engels, has been put. I take as my central exhibit Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s influential, putatively non-teleological Anti-Oedipus (1972, trans 1977). With a close reading of an important section called “Savages, Barbarians, Civilized Men” --a section that borrows Morgan’s categories and method exactly without citing Ancient Society-- I argue that the ghosts of Morgan’s historiography haunt even Deleuze and Guattari’s explicitly anti-progressive, “rhizomatic” framework. From Deleuze & Guattari’s 1972 text I move to a pair of more recent volumes, Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri’s Deleuzian studies of globalization and power, Empire (2000) and Multitude (2004), books Fredric Jameson has called “the first great new theoretical synthesis of the new millennium.” To the developmental ideologies their authors read in contemporary global empire, these works look to offer a flattened, horizontal countermodel – a “break with teleology,” as Multitude puts it. I argue that in tension with their stated aims, however, even these works cannot help but re-deploy a narrative logic already set forward by Morgan and inherited by Deleuze. The specters of humanity’s march to civilization animate, still, major paradigms on the contemporary left. I close by returning to Morgan, suggesting that we might revisit Ancient Society as the staging ground of a particularly current critical problem, namely the precise ethical valence of “progress.” In this context, I argue that with its unresolved vacillation between approval of “development” and romanticization of a lost past, Morgan’s own text might function as a kind of metacritical allegory particularly useful to us in a moment when the legacies of intellectual progress appear so simultaneously positive and negative – and, perhaps, inevitable. Put shortly: in Ancient Society’s ambivalent rendering of an upward passage through states of knowledge, doesn’t Morgan sketch a plot in which we all, as critics, can’t help but participate? NATHAN K. HENSLEY Duke University nathan.hensley@duke.edu