Definition of Status Epilepticus(Lowenstein DH. 1999)

advertisement

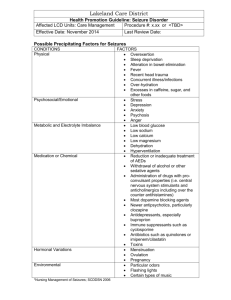

Overview of Status Epilepticus Kassandra Barkley, ANP-BC Department of Neurology Vanderbilt Medical Center Definition of Status Epilepticus(Lowenstein DH. 1999) • Traditionally defined as continuous, unremitting seizure lasting longer than 30 minutes, or recurrent seizures without regaining consciousness between seizures for greater than 30 minutes. • Newer literature and common neurology practice usually accepts 5 minutes or longer as definition for status epilepticus. Epidemiology (Alldredge et al 2001) • In the United States, the incidence is around 18-41 per 100,000 people per year • Mortality rate can be around 20%, especially if treatment is not initiated quickly – Highest mortality occurs with anoxic and cerebrovascular causes – Seizure duration is greatest predictor of mortality. SE lasting > 1 hour has significantly higher mortality *Better prognosis: AED withdrawal in patients w/ epilepsy and ETOH related etiologies Epidemiology • Most common in ages > 60 & < 12 months • Approximately 10% to 15% of patients with chronic epilepsy will experience an episode of SE at some point of their clinical course. • Approximately 7% to 10% of patients with chronic epilepsy initially present with an episode of SE. Epidemiology • At a health economics level, SE costs approximately $4 billion per year in the United States . Epidemiology • In Neuro Intensive Care Units, up to 1/3 of patients will have nonconvulsive seizures and most of these will be in nonconvulsive status epilepticus (Jordon KG 1994) • In Medical Intensive Care Units, up to 10% of patients undergoing continuous EEG monitoring have nonconvulsive seizures (Towne AR et al 2000) ETIOLOGIES OF STATUS Antiepileptic drug (AED) noncompliance/insufficient dosing 20% CNS infection 5% Old brain injury 15% Cerebral tumor 5% Acute vascular injury 15% Acute Trauma 5% Alcohol related 10% Drug toxicity < 5% Metabolic/electrolyte disturbances 10% Global hypoxic injury < 5% Unknown/cryptogenic 10% Idiopathic epilepsy < 5% TIME IS BRAIN!! TIME IS BRAIN • Status should always be treated as an emergency and be treated promptly! Physiologic Changes in Status Epilepticus • Phase 1: Compensation (First 30 mins) – During this phase, cerebral metabolism is greatly increased because of seizure activity, but physiological mechanisms are sufficient to meet the metabolic demands, and cerebral tissue is protected from hypoxia or metabolic damage. The major physiological changes are related to the greatly increased cerebral blood flow and metabolism, massive autonomic activity, and cardiovascular changes Phase 1: Compensation Physiologic Changes Increased brain metabolism w/ increased use of oxygen & glucose Elevated systemic and pulmonary artery pressures Increased cardiac output Hypertension Tachycardia Cardiac arrythmias Hypercalcemia Lactic acidosis Massive catecholamine release Hyperthermia Incontinence Vomiting Physiologic Changes in Status Epilepticus • Phase 2: Decompensation (After 60mins) – During this phase, the greatly increased cerebral metabolic demands cannot be fully met, resulting in hypoxia and altered cerebral and systemic metabolic patterns. Autonomic changes persist and cardiorespiratory functions may progressively fail to maintain homeostasis Phase 2: Decompensation Physiologic Changes Failure of cerebral auto-regulation. Cerebral blood flow dependent on systemic BP Respiratory and cardiac impairments (pulmonary edema, PE, cardiac failure, respiratory collapse) Hypoglycemia Systemic hypoxia Hypotension Falling cardiac output Hepatic & Renal dysfunction Metabolic & Respiratory Acidosis Hypokalemia; Hyperkalemia Consumptive coagulopathies Falling lactate lvls Rhabdomyolysis Multi-organ failure Hyperthermia Leukocytosis Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) Types of Seizures • Seizures can manifest as motor, sensory, or cognitive dysfunction • Classification of seizures – Partial – seizures localized to an area of the brain resulting in a corresponding localized dysfunction. Often described by presence of absence of automatisms (ie lip smacking, jaw mvmts, swallowing, fumbling with nearby objects) or repeated subconscious or involuntary movements . • Simple (w/o impairment of consciousness) • Complex (w/ impairment of consciousness) **Please note partial seizures can develop into secondarily generalized seizures as abnormal electrical activity spreads through the brain Classification of Seizures - Generalized seizures are characterized by the resulting dysfunction -Absence (loss of consciousness with no motor dysfunction) -Myoclonic (bilaterally synchronous, arrythmic jerking) -Clonic (repetitive and rhythmic motor movement) -Tonic (extension of the arms, legs, & trunk) -Tonic-clonic (extension of the arms, legs, & trunk followed by repetitive, rhythmic movement) -Atonic (aka drop-attack, absence of motor movement) [Parillo & Dellinger, 2008] Frontal Seizure with vocalizations, and hypermotor activity Partial seizure w/ secondary generalization Types of Status Epilepticus • CONVULSIVE – Generalized (Most common presentation of SE) • • • • Myoclonic Clonic Tonic Tonic-Clonic – Partial • Simple • Complex • Secondarily Generalized Types of Status Epilepticus • SUBTLE CONVULSIVE – About 30% SE population – Longer duration & more difficult to treat – Clinical features: • • • • • • Continuous rhythmic subtle motor phenomena Facial twitching, nystagmoid eye jerks Subtle twitching of trunk or extremities Cognitive impairment (altered awareness) Head or eye deviation Automatisms Types of Status Epilepticus • NON-CONVULSIVE – Generalized • Absence • Atonic – Partial • Simple • Complex • Secondarily Generalized Possible Findings in Convulsive Status • Generalized convulsions w/ bilaterally symmetric myoclonic, tonic, clonic, or tonicclonic movements • Convulsions on 1 side of body (not symmetric) with repetitive involuntary movements Possible findings in Non-convulsive Status Behavioral, cognitive, or sensory findings: – Agitation, aggression, amnesia, aphasia muteness, catatonia, coma, confusion, delerium, delusions, hallucinations, laughter, perseveration, singing, psychosis Autonomic: • Abdominal sensation, apnea, hyperventilation, brady or tachyarrythmia, flushing, miosis, mydriasis, hiccups, nausea, vomiting Motor: – Automatisms, dystonic posturing, eye blinking, eye deviation, facial twitching, finger twitching, nystagmus, tremulousness Responsiveness of Treatment of SE • Treatment with 1st line therapy within 30 minutes of onset stopped status in 80% of patients • Treatment with first line therapy started >/= 2 hrs after onset stopped status in 40% of patients Monitoring For Status in the ICU…… • Continuous EEG [cEEG] (continuous EEG 24 hr order in WIZ) is ideal for capturing seizure activity • Using cEEG captures 56% of seizures in first hour and 88% of seizures in first 24 hrs (Sutter et al 2013) • Note: some factors which may limit obtaining and/or interpreting EEG include head bandages, delerium w/ mvmts, sweating, and aritifact from electrical interference of mechanical devices ie vent, ECT, dialysis. Also availability of EEGs in the hospital plays a role INITIAL MEDICAL MANAGEMENT • • • • ABCS (airway, breathing, circulation) Obtain IV access (2 sites preferably) Check finger stick glucose Give thiamine 100mg IV prior to Dextrose D50W 50ml IV if low or unknown glucose • Continuous monitoring (ECG, BP, HR, oxygen) • Send stat labs (CBC, BMP, LFTs, Ca, Mg, PO4, troponins, ABGs, AED lvls if on seizure meds, tox screen (urine, blood), Hcg if pregnancy possible • Continuous EEG, stat neurology consult Obtain history & exam • History of epilepsy & AED use, structural brain lesion (stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, tumor), head trauma, meningitis, social history (illegal drug or ETOH use), pregnancy • Medical History including medications • Seizure onset & duration, description of seizure • Full neurologic exam including mental status, cranial nerves, motor exam, sensory exam, reflexes, cerebellar testing Treatment of Convulsive SE First Line Agents: •▪Lorazepam Load IV 0.1mg/kg up to 4mg (2mg/min) •▪Midazolam Load IM 0.2mg/kg up to 10mg IM •▪Diazepam Load 0.2mg/kg (20mg rectally or 10mg IV) Second-Line Agents •▪Fosphenytoin 20mg/kg infused at a rate of 150mg/min •▪Valproate 20-40mg/kg infused at a rate of 6mg/kg/min •▪Levetiracetam 1500-4000mg infuse 500mg/min •▪Lacosamide 400mg IV infuse over 5 mins •▪Phenobarbital 20mg/kg IV infuse 60mg/min Treatment of Convulsive SE Third Line Agents • ▪Midazolam infusion (Hypotension, withdrawl seizures) • ▪Propofol infusion (Hypotension, propofol infusion syndrome) • ▪Pentobarbital (Ileus, metabolic acidosis, thrombocytopenia, immunosuppression) • ▪Ketamine infusion (Hypertension, possible rise in ICP) • ▪Etomidate infusion (Adrenal insufficiency, non-epileptic myoclonus) • ▪Lidocaine administration every 5 minutes (cardiac arrhythmia) Treatment of SE Oral Agents •▪Topiramate 400-800mg/day (metabolic acidosis •▪Pregabalin 150-600mg per day •▪Vigabatrin 0.5-1gr q8h (no short term side effects) Summary • Status is an emergency & requires immediate treatment • Remember sometimes status seizures are not obvious, symptoms can be very subtle or may only present as altered mental status • If you are concerned about seizures, consult neurology right away for continuous EEG monitoring References • • • • • • • Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus: an overview of the clinical problem. Epilepsia 1999; 40(Suppl 1); discussion S21-22 Jordan KG. Status epilepticus. A perspective from the neuroscience intensive care unit. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1994;5:671-686 DeLorenzo RJ, Pellock JM, Towne AR, Boggs JG. Epidemiology of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurophys 1995 Jul; 12(4) 316-25 Allredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo fo the treatment of out of hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 2001; 345(9):631-637. Towne AR, Waterhouse EJ, Boggs JG, Garnett LK, Brown AJ, Smith JR Jr, DeLorenzo RJ. Presence of nonconvulsive status epilepticus in comatose patients. Neurology 2000;54:340-345 Parillo JE & Dellinger RP. (2008). Critical Care Medicine: Principles of Diagnosis and Management in the Adult. St Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier Sutter, R, Stevens R, and Kaplan P. Continuous Electroencephalographic Monitoring in Critically Ill Patients: Indications, Limitations, and Strategies. CCM Journal. 2013, 41(4) 1124-1132