Ultimately my research is turned towards a concern that the way we

advertisement

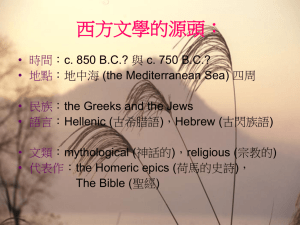

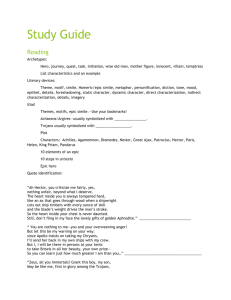

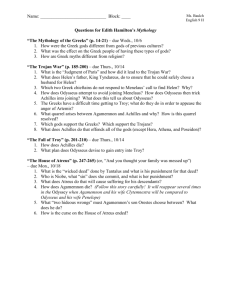

Trevelyan Prize talk on: "Speech and Society in the Homeric Epics": 17/06/2013 Good evening, I am here to present to you all an introduction to my research on "Speech and Society in the Homeric Epics". I intend to begin by introducing the key general elements of my research, namely, the Homeric poems themselves, and the sociolinguistic methodology which forms the foundation of my approach to reading these poems. In the second half of this talk I will turn to passages from the texts to illustrate the deeper nuances which I believe can be teased out of the text by interpreting the poems in this way. I shall now give a brief introduction to the Homeric Epics for those who are unfamiliar with them as well as a short discussion of their nature and the prevailing scholarly attitudes towards them which will show why this research is needed. The "Homeric Epics" is a generic term for referring to the Iliad and the Odyssey. These are two monumental poems, composed in an artificial poetic dialect of ancient Greek, and are recognised as the first two works of western literature. The dating and the identifying of the author of these works has been questioned and debated since antiquity. Herodotus, the so called father of history, or if you prefer to follow Cicero, the father of lies, writing in the fifth century BC believed Homer to have written the poems about five hundred years before his time. However modern scholarship addressing this issue tends towards dating the Iliad in the mid to late eight century BC with the Odyssey composed perhaps a generation later. One of the great leaps forward in our understanding of Homer in the last century was the discovery by Parry and Lord of the oral nature of the epics by comparing them with the living oral poetry extant in what was then Yugoslavia. Now the Iliad and the Odyssey are not exactly short poems. The first is of approximately 15,000 lines of hexameters and it has been estimated that it would take pretty much a 24 hour day to perform fully so the idea that they were composed and performed orally, that is, without the aid of writing, initially seems hardly fathomable. And yet, from the archaeological discoveries of the Mycenaean civilisation which flourished around the Aegean until the twelfth century BC, and the linguistic evidence of the Linear B writing tablets which have been preserved from that civilisation, it is fairly assumed that the Homeric poems look back, through the so called 'dark age' of the tenth, ninth, and early eighth centuries in Greece, a period in which many settlements were sacked or abandoned, which may have been marked by the migration of new peoples into or through the area, and in which writing disappeared completely, to this former time, which later Greeks came to see as their 'heroic' age. This gives perhaps three centuries during which the tales of this heroic age were celebrated orally in song, and developed through expansion and refinement, into not just the Iliad and Odyssey but into a whole corpus of epic poetry, some of which is remembered in myths which come alive in Classical era tragedy or Hellenistic period epic, but much of which is lost to the sands of time. There must of course then have been something in the nature of the poems which allowed them to be preserved orally and passed on across the generations. Much of the Homeric scholarship of the latter half of the twentieth century has preoccupied itself with identifying the features of Homeric poetry which enabled the bards to remember, recall, and re-perform these tales time and again. In his 1928 work " L'Épithète traditionelle dans Homère: Essai sur un problème de style homérique" Milman Parry addressed one aspect of the style of Homeric poetry which can handily work as an example of how the bard minimised the effort of recollection during performance. Parry noted that the names of the heroes were often accompanied by little tag phrases or epithets, usually adjectives. Hence Achilles is often 'Swift Footed', Odysseus 'Much Suffering', men are 'godlike' and women are 'lovely-haired'. Parry worried that some of these epithets were often ill applied, for example he thought that calling Achilles 'swift footed' as he sits on the sea shore weeping is perhaps less appropriate than when he is called such in the heat of battle, where his fleetness of foot was his great asset. Parry hypothesised that the reason this occurred was because it was a handy way for the poet of filling out the hexameter line. The dactylic hexameter is the meter in which the Homeric poems were composed and is based on a combination of long and short syllables. Essentially, there are six feet in each line and each foot consists of one long syllable followed by two short, but in all but the fifth foot, the two short syllables in the second beat of each foot can be substituted for a long syllable. So an example line would be: – – | –υυ|– υ υ|– υ υ | – υ υ|– – νῦν δὴ νῶι ἔολπα Διῒ φίλε φαίδιμ᾽ Ἀχιλλεῦ 22.216 Parry argued that the 'essential idea' in the second half of this line was Achilles, and that the epithet φαίδιμ᾽ which occurs in numerous other lines with Achilleu in the final two feet, was merely stylistic padding so that the poet could roll out the dum di di dum dum at the end of the line with ease and start thinking about how the next line was to begin. This is but one of a range of elements of Homeric style which hint at their oral or orally derived nature. However, it is with these notions of 'stylistic padding' and 'essential idea' which my research takes issue. While I am fully convinced of the orality of the two poems, I do think that the way in which this orality is described oversimplifies the language of epic, at the expense of much of the nuance that variation in language style can imply. The more recent work of David Shive (1987) on "Naming Achilles" showed how Parry was wrong to think that there was only one metrical way of expressing an 'essential idea', such as the idea of Achilles. By adapting some of the theories of Sociolinguistics I hope to demonstrate how this notion of an 'essential idea' is of itself fundamentally misguided and so account for the greater formulaic variety found by Shive than Parry predicted. In order to show this I am investigating the language of the characters in the Homeric poems. Approximately 45% of the Iliad and 67% of the Odyssey constitute direct character speech. Indeed in his Poetics Aristotle calls Homer a Tragedian before the advent of tragedy as a genre because of the way in which he lets his characters speak for themselves and removes as much as possible the narrative voice from the action. Contra Parry's notion of the 'essential idea' I argue that there is a degree of social force behind the characters' linguistic expressions which accounts for the greater formulaic variation. Two quick English examples I believe can illustrate this point. Let's say the ink in my pen has ran out an I have to ask someone for a new one. If I were sitting in the Mowlam room with Patrick I might get away with just saying 'pen' with the correct intonation. But encoded alongside the request would be a social force saying that our friendship has evolved to such a point that rhetorical niceties can be dispensed with. However were I to attempt to borrow a pen off Dr Latham in the same linguistics manner not only would I perhaps be unsuccessful but surely it would only work to confirm how impolite and barbaric Makems can be. To understand the social forces at play influencing language choice we turn to some of the ideas of sociolinguistics. One of the ideas I am bringing over from that area of study is that the social context of an utterance plays in influencing role on the form which that utterance takes. Social context generally constitutes firstly the relationship between the speaker and hearer (typically defined in terms of the power difference between them, and the solidarity or intimacy between them), (2) the cultural context of the speech (location, formal setting, or more generally the result of the processes of socialisation which inform a person's expectation of what language is appropriate for the given relationship which they perceive the exist between themselves and their interlocutor(s)). Another sociolinguistic tool which I wish to bring to reading Homer is Politeness Theory. Following Brown and Levinson 1987 politeness is related to one's social face. This is marked by two key "face wants", firstly to not be imposed upon and secondly to have others approve of your action. These face wants give us what is respectively referred to as negative and positive politeness which are a range of linguistic strategies that are spawned for redressing face threatening actions. Negative politeness thus focuses on minimising imposition. Directives for example, in which the speaker generally wishes to get the hearer to something, are inherently threatening to a person's negative face, or their want not to be imposed upon, as such they are often marked with negative politeness strategies. Thus a social superior may well address their underling with a simple imperative such as "hand that essay in by Friday", a directive in the opposite direction might well take a form which incorporates a number of negative politeness strategies such as indirectness and optionality, for example "would it perhaps be possible if you were able to give me an extension on the essay until next Monday please, sir?" Language as it is being produced and received is constantly being evaluated in terms of whether it is in keeping with what is expected given its social context. Watts, 1992, employed the term 'politic' language to describe language which is felt to be in keeping with what is expected, with polite and impolite, used to describe language which strays either side of politic. I shall now briefly use the first two speeches of the Iliad to bring some of the ideas just discussed to the Homeric poems. The Iliad opens with a priest of Apollo, Kryses, appealing to Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek forces at Troy, to release his daughter Kryseis who has recently been captured by the Greeks. Ἀτρεΐδαι τε καὶ ἄλλοι ἐϋκνήμιδες Ἀχαιοί, ὑμῖν μὲν θεοὶ δοῖεν Ὀλύμπια δώματ᾽ ἔχοντες ἐκπέρσαι Πριάμοιο πόλιν, εὖ δ᾽ οἴκαδ᾽ ἱκέσθαι: παῖδα δ᾽ ἐμοὶ λύσαιτε φίλην, τὰ δ᾽ ἄποινα δέχεσθαι, ἁζόμενοι Διὸς υἱὸν ἑκηβόλον Ἀπόλλωνα. Sons of Atreus and you other well equipped Greeks, To you may the Gods who live on Olympus grant To sack the city of Priam, and to arrive home safe. But would that you might release my dear child to me, and accept this ransom, Respecting the child of Zeus, far-shooting Apollo. (Iliad 1.17-21) There are a number of aspects of this speech which are of interest. First of all the chosen form of address Ἀτρεΐδαι. Paul Brown, in an article conveniently called "Addressing Agamemnon: A Pilot Study of Politeness and Pragmatics in the "Iliad"" notes that the patronymic form of address, that is one that refers to one's father, as is the case here where Agamemnon's father Atreus is mentioned, have a tendency to occur when there is a greater degree of social distance between the interlocutors. Thus, as a further example of this, Agamemnon's Trojan enemies never use his name, but always his patronymic. By using this form here, Kryses is acknowledging the social distance in terms of both intimacy and power that exists between them. After his opening address, Kryses attends to his audience's positive face, he butters them up, so to speak. He 'claims common ground' with the Greeks by conveying that he finds desirable their ultimate desire to sack Troy and return home. Furthermore, in recognition that by requesting something from Agamemnon, he potentially leaves him less well off than before, he offers to recompense Agamemnon's want for the spoils of war by offering a ransom. When it comes to the main focus of his speech, his directive to Agamemnon to free his daughter, he uses λύσαιτε - a verb in the optative mood. The optative in Ancient Greek is used to express wishes or potentiality which is why I have translated it here as " would that you might release my dear child to me". Kryses' choice of verbal mood acknowledges Agamemnon's ability to refuse his request, introducing and recognising the degree of optionality in Agamemnon's response, in a way that an imperative for example would not. Kryses then, uses a mixture of positive and negative politeness strategies in an attempt to persuade Agamemnon to free his daughter. The response of the Greeks assembly to Kryses' speech indicates that they think the tone in which he has cast his request is generally appropriate to the context in which it is made: ἔνθ᾽ ἄλλοι μὲν πάντες ἐπευφήμησαν Ἀχαιοὶ αἰδεῖσθαί θ᾽ ἱερῆα καὶ ἀγλαὰ δέχθαι ἄποινα: Then all the other Achaeans shouted their support That he should respect the priest and accept the splendid ransom. Iliad 1.22-3 In other words, they interpret Kryses speech as politic, it is in keeping with the tone of language which would be expected for a suppliant to employ. Agamemnon, however, is not so politic in his reply: μή σε γέρον κοίλῃσιν ἐγὼ παρὰ νηυσὶ κιχείω ἢ νῦν δηθύνοντ᾽ ἢ ὕστερον αὖτις ἰόντα, μή νύ τοι οὐ χραίσμῃ σκῆπτρον καὶ στέμμα θεοῖο: τὴν δ᾽ ἐγὼ οὐ λύσω: πρίν μιν καὶ γῆρας ἔπεισιν ἡμετέρῳ ἐνὶ οἴκῳ ἐν Ἄργεϊ τηλόθι πάτρης ἱστὸν ἐποιχομένην καὶ ἐμὸν λέχος ἀντιόωσαν: ἀλλ᾽ ἴθι μή μ᾽ ἐρέθιζε σαώτερος ὥς κε νέηαι. Do not let me, old man, meet you by the hollow ships Lingering about now or coming again later, Your staff and god's wreath would not aid you. I will not release her, before old age finds her In my home, in Argos, far from her fatherland Working the loom and sharing my bed. But go, do not anger me so that you may more safely depart. Agamemnon explicitly rejects Kryses' request but he goes beyond a mere rejection, into a threat, certainly he is not listening to the encouragement of the other Greeks who urge him to respect the fact that the suppliant is a priest of Apollo, as he says that the symbols of his office, his staff and wreath, will offer him no aid. The two μή s which open lines one and three of this speech set its negative tone, leading up to explicit τὴν δ᾽ ἐγὼ οὐ λύσω; "she I will not release". While the first half of this speech contains a hint of showing disrespect to the priest's status, the second half of the speech is where Agamemnon really rubs in how he will treat his captive. Agamemnon's description of Kryses' daughter deported from her homeland, working as a slave in his household and sharing his bed must play upon a father's deepest and darkest fears of what can become of their daughter. Agamemnon is metaphorically trampling all over Kryses' social face, making real with his words Kryses' most dreaded reality. While Kryses has tried to ingratiate himself to Agamemnon and the Greeks by playing on their greatest desire, to sack Troy and return home, Agamemnon plays on a fathers greatest fear. Being the anax andron, the lord of men, it is undoubtedly his right to accept or refuse Kryses' offer of a ransom, but it is hard not to see his impolite, disrespectful and taunting tone as responsible for what happens next. For those of you who just haven't quite got round to reading the Iliad yet, Kryses goes off and prays to Apollo to curse the Greeks with a plague, with lots of them dying Achilles recalls the assembly and with the help of a seer learns that Apollo is punishing them on account of Agamemnon's treatment of Kryses and will only stop when the girl is returned without ransom. Achilles urges Agamemnon to return her. Agamemnon is upset that he'll be the only hero missing out on a share of the spoils of war so threatens to take Achilles' slave girl to make up his own loss, and things generally start to kick off from there. But I'll leave it to you all to discover for yourselves the rest. Ultimately my research is turned towards a concern that the way we have thought about Homer as an oral poet has been perhaps too mechanical and too oversimplifying in an attempt to comprehend how such a massively long and complex work of art could be produced without the aid of writing on which we especially now so heavily rely. I hope that by showing how the language of the characters is much more natural than rigidly formulaic in its variation to its social context, the nature of the Homeric poems, as speech themselves, are more naturally tuned in to the nuances of common Greek language than has previously been appreciated.