Burnt Cork and Water Abstract The cinematic experience of minstrel

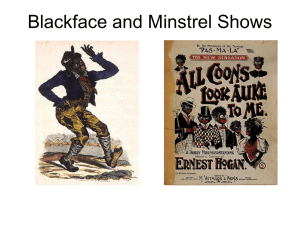

advertisement

Burnt Cork and Water 1 Abstract The cinematic experience of minstrel shows as we know it changes when we introduce an interracial element into what we think of when there is discussion of minstrel shows today. The purpose of this paper is to identify the ways in which advertisement shaped a Fort Wayne audience member’s expectation of upcoming shows. In the late nineteenth and twentieth century the audience had not yet come to know what a genre was or meant to a live show audience; yet the publicity of minstrel shows reinforced certain common themes that were evident in an audience member’s experience. Finally, the introduction of race as an interracial element changes the way we view minstrel shows in that when one mentions a minstrel the general consensus of today is thoughts of a white man in black face. This paper also explores the implications of race when this interracial element is introduced to a Fort Wayne audience’s cinematic experience, when it is not a white man in black face, but black artists. Introduction According to Allen and Gomery (1985) the assumption that cinematic stereotypes reflect stereotypic attitudes within society underlies several works that examine the image of blacks in American cinema. For example, in To Find an Image: Black Films from Uncle Tom to SuperFly, James P. Murray argues that films reflect “what people think of themselves in relation to the world.” In much of the literature on black screen images the concern is expressed that 1 Burnt Cork and Water 2 stereotypic images affected as well as reflected public attitudes toward blacks. The effect of Hollywood’s representation of blacks, says Murray, was to reinforce the notion among both blacks and whites that “it was whites, not blacks, who were significant” in American society. (pg. 159) There is no denying that minstrelsy of the late nineteenth century was a largely whiteowned and white-performed social phenomenon. One might ask why these shows are such a phenomenon and what is their significance, but when one considers the peculiar institution of slavery, post slavery ideology and romanticism of racism, and social norms that reinforced racist ideology; the presence of minstrel shows and the introduction of blacks in the performance of these shows raises a much larger question of why and how did blacks perform in these shows and the modes of reception from Temple audience members. 2 Burnt Cork and Water 3 3 Burnt Cork and Water 4 4 Burnt Cork and Water 5 Dorman (1988) describes this phenomenon as the “coon song craze” circa 1890-1910. These images and representations of the caricatures in these shows were “ignorant”, “maladroit”, and “outlandish” in its misuses of the forms and substance of white culture. While they were normally portrayed as happy go-lucky dancing, singing, joking buffoons, they were above all either humorous or pathetic. In either case according to Dorman (1988) these caricatures were safe figures and the accepted version of what was commonly perceived as the “real” American black. Additionally, when these shows are performed by all black casts or blacks artist as a part of these performances; this fascination for this caricature as a mass form of entertainment becomes more problematic. In that the performance of black artist in these shows is symbolic of a “real” black experience to a white audience who interaction with blacks of the time would have been either “confirmed” or embellished”. Significance of Race The historical context in which blacks or African Americans have been identified over the context of time by whites is fluid. In that using identifiers to identify race by a white audience over this context of time, is to use language such as negro, colored, black, and/or AfricanAmerican. In the context of time that this paper explores the language will be used interchangeably by using language of the time that identified blacks or African-Americans as Negro or colored. The fluidity that exists in identifying race of the late nineteenth and earlier twentieth century is also representative of this same fluidity. The language of the time when identifying race used the language as negro to identify black. However, to promote shows the language that identified race changes and becomes “colored” to promote these minstrel shows. “Burnt Cork and Water” The Minstrel Show 5 Burnt Cork and Water 6 Friday May 3, 1895, Stouder and Smith managers of the then Masonic Opera House proposed to offer three shows for the price of one admission. This is an indication that minstrel shows were on the decline amongst Fort Wayne audience members. On the same day in the News Billy B. Van argues that minstrelsy will never be the same. “Billy Van, a veteran minstrel, says there is no longer such thing as real Negro minstrelsy. Van gives readers a glimpse of what minstrelsy was to a Masonic Temple audience and how these shows will change for viewers. In the late nineteenth and twentieth century the audience had not yet come to know what a genre was or meant to a live performance show audience; yet the publicity of minstrel shows reinforced certain common themes that were evident in an audience member’s experience. In the viewing of the minstrel shows a Fort Wayne audience had come to expect certain viewing experiences and some common themes can be generated. For example, in Billy Vans article he writes, Part One: “commenced with the first part…40 men sitting in a semi circle…at the end of this semi circle were usually three men called bones and tambo...named according to the instruments they played. At the rise of the curtain you had the “interlocutor” or narrator who would say gentlemen please be seated; then the orchestra would gallop, then end men “tambo and “bones” would accompanying the orchestra “and then different men would use the “dialect of the Negro perfectly…” Van further states, “Everyone is in blackface” and the first part only “tended to make one believe he was witnessing a negro jubilee…” “…The costumes consisted of black pants to the knees, red coats, yellow vests, and wide collars, with bushy hair…” Then he talks about the present day 1895, only the end men are in black face and the rest of the cast is white…” “The Negro character is almost lost…” and “anything that maybe seem to be funny in a minstrel show at the present day is told as a negro joke…” Arguably, what is interesting is that the connection could be made between the article and the admissions sale (three shows for the 6 Burnt Cork and Water 7 price of one); and a conclusion could be made about the decline of these shows as follows. The minstrel show had lost its “zest” for life amongst Temple audiences. Had audience members grew tired of the common themes in these live shows? Had the relationship between race in society and the racist dialogue that these exhibited changed and the Temple audience grew tired of it and changes had to be made? These are questions that remain unanswered. Discussion & Analysis “An advance argument” As stated previously in the paper these shows were largely owned by whites and the significance of black artists in these shows means that they—black artists, would have been hired by whites. That being said raises more questions that this paper does not explore, but has the potential for future research and exploration. The significance of blacks in minstrel shows implies that blacks in addition to whites used “blackface” entertainment as a form of occupation. Black artists would have traveled alongside whites to the Fort Wayne area and would have with whites performed at the Masonic Temple Opera House. This paper also does not explores what these performers would have experienced as visitors to the area or experienced at the Opera House, but there is potential for research to answer such question as: What were the social norms of the time? Did the Masonic Temple Opera House have separate areas for Black performers? Did they use different entrances for blacks than white performers? When introducing this element of interracial performances at the Temple there with it introduces many more questions that can be answered in future research. Some challenges in the research of this interracial element of minstrel performances at the Masonic Temple Opera House is that in unraveling the complexity of understanding minstrelsy and audience experience means trying to find adequate meaning and answers to what blackface 7 Burnt Cork and Water 8 meant to Temple audience members. Meaning what would “blackface” have meant to a white audience? Does this blackface performance reinforce stereotypical images of blacks and continue racist dialogue between Blacks and Whites in the area at the time? All of which this research fails to answer, but has the potential to do so in the future; given more time, as time was a constraint in this research and being a novice of research methods in this area of research. 8