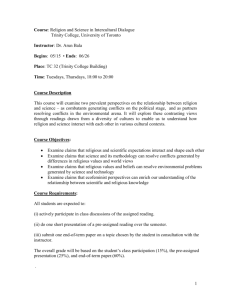

Required Readings - University of Alberta

advertisement

POLITICAL SCIENCE 333A1 Fall 2012 ECOLOGY AND POLITICS Tues and Thurs. 11:00 – 12:20, Tory T 1-90 Instructor: L. Adkin, Ph.D., Assoc. Professor Office: Tory 12-27 492 0958 ladkin@ualberta.ca “Knowledge is about the past; Wisdom is about the future.” (Cree elder quoted by artist Jane Ash Poitras in a mixed media exhibit at the Edmonton Art Gallery in 1992.) Course Description: This course begins with an introduction to political ecology as an integrated, multi-scalar theoretical framework for examining socio-environmental problems. The two key approaches utilized are political economy and discourse analysis. The Dryzek book, Politics of the Earth, provides a set of categories of environmental discourse, including: “limits to growth,” “Prometheanism” (or the denial of limits to growth in liberal economic thought and the rejection of the precautionary principle in scientific-technocratic discourse), and; “sustainable development.” To these I add more focused considerations of ecocentrism, indigenous knowledge, and environmental justice, as well as a feminist historical analysis of the nexus between capitalism, patriarchy, and science (Merchant’s The Death of Nature). Environmental discourses address such questions as: Is there an “environmental crisis? If so, what are the causes? What are the solutions? We ask: What social, economic, and political interests underpin these discourses, and what are the implications of their interpretations and prescriptions for socio-ecological futures? If their explanations conflict, how do we choose among them? On the basis of “scientific evidence”? Principles of ecology? Faith in the market and in human ingenuity? Commitments to social justice? What is the meaning of “sustainable development”? Who is responsible to do what? Course Goals: to develop students’ abilities to evaluate critically the discourses that interpret the meaning of ecological problems. It introduces the political economy and actor-centered (discourse analysis) approaches used by political ecologists, and gives students opportunities to use these in evaluating course material and in researching subjects of particular interest to them. to develop analytical, writing, and research skills. Prerequisites for Pol. S. 333: Students without the course prerequisite should communicate with the instructor before registering. At the request of the instructor, the Department may cancel your registration if you do not have the required course prerequisites. To register in this course you must have POL S 230 or 240 or consent of the instructor. An introductory-level background in political theory and political economy is necessary to comprehend the material in this course. This course is not designed for 1st and 2nd year students. Comparable prerequisites from other faculties (e.g., the ENCS programme in ALES) will be considered. If you have not already done so, please email the instructor details of the courses you have taken that may serve as prerequisites for Pol. S. 333, including their titles and course numbers. Class format: The course combines lectures with class discussions, films, guest speakers (as available), and occasional exercizes such as simulations or small group work. A website provides an additional venue for interaction, as well as access to many required and supplementary materials. 1 Required texts (available in the Campus Bookstore, SUB) Laurie Adkin, ed., Selected Readings for Pol. S. 333 A1 Fall 2012 Ecology and Politics. Students’ Union Printer, University of Alberta, Fall 2012. John S. Dryzek, The Politics of the Earth (Environmental Discourses). 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2005. Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. San Francisco: Harper & Row Pubs., 1980. Leo Panitch and Colin Leys, eds. Coming to Terms with Nature: Socialist Register 2007. London: The Merlin Press, 2006. Recommended (copies ordered for Campus Bookstore) Jeff Rubin. Why Your World Is About To Get A Whole Lot Smaller (Oil and the End of Globalization). Random House Canada, Ltd., 2009. Michael Maniates and John M. Meyer, eds., The Environmental Politics of Sacrifice (Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2010). COURSE WEBSITE: http://polsci333.pbworks.com/ REQUIREMENTS AND EVALUATION The course requirements are outlined below. Students should note that in all but exceptional situations, all components of the course must be completed to receive a passing grade. Policy regarding missed term work is outlined in Section 23.4(3) of the University Calendar. Tests and assignments will be assigned a letter grade. A+ will be represented by 4.3. Attendance: To pass this course you must attend a minimum of 16 / 25 class sessions: Pass/Fail grade Class participation: 15 per cent (see pages 13, 22 of syllabus) Three short (750 words, 3 page maximum)“focus papers,” one due no later than October 4; one due no later than October 30; one due no later than November 20. (November 20 is the last date on which I will accept focus papers.) Each is worth 15 per cent of your grade. Up to five papers may be submitted; I will take the “best three” grades. Detailed instructions for these assignments are provided on pp. 15-20, and will be discussed in class. 12-page research essay, due November 27: counts for 40 per cent of final grade. For details, see p. 21of the course syllabus. Please note: to be handed in, printed, in class. No final exam. 2 How I grade: When grading assignments I use my judgment, based on 22 years of teaching, regarding where a paper falls on the grading scale, and using the criteria that I have provided. (I do not use a grades distribution chart to assign grades.) When calculating final grades, I use a combination of considerations, listed in order of importance: the numerical score resulting from the assignment grades (these are not curved or adjusted to any preset formula); evidence of individual improvement and effort over the term (comes into play when a final grade is border-line); the overall performance of the class. The last consideration is more likely to influence grade distribution in a large class than in a seminar class, if the mean grade differs significantly from the GFC’s mean for a course at that level, and if there are no apparent justifications for this variation. (Classes do perform differently, overall, depending on the level of preparation and abilities of their constituents, although such variations in class averages are generally smaller the larger the class size.) Note that the Department of Political Science now has a policy that: "Grade appeals regarding term work must be initiated before the final exam is written, unless the work is handed back at the final exam." Rules for extensions and late penalties: It is your responsibility to inform the instructor as soon as it becomes clear that your work will be late. Extensions will be granted in the case of illness or personal crisis. Extensions must be requested before the due date for the assignment. In fairness to students who have completed their work on time, there will be a penalty for late papers for which extensions have not been granted. The penalty for late papers will be 0.2 points per day (e.g., a 4.0 paper one day late will receive 3.8; a 2.7 paper two days late will receive 2.3). Papers more than five days late will not be accepted. An extension for an assignment due at the end of the term may result in a grade of incomplete, due to grade submission deadlines in December. Please note that, beyond certain limits, extensions may only be granted by the Faculty of Arts and under specified, medically documented conditions. Undergraduate Student Grading Scale Descriptor Excellent Good Satisfactory Poor Minimal Pass Failure Letter Grade Grade point value/Numeric equivalent A+ A AB+ B BC+ C CD+ D F 4.0 (4.3) 4.0 3.7 3.3 3.0 2.7 2.3 2.0 1.7 1.3 1.0 0.0 Plagiarism & Academic Dishonesty: The University of Alberta is committed to the highest standards of academic integrity and honesty. Students are expected to be familiar with these standards 3 regarding academic honesty and to uphold the policies of the University in this respect. Students are particularly urged to familiarize themselves with the provisions of the Code of Student Behaviour (online at http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/gfcpolicymanual/content.cfm?ID_page=37633) and avoid any behaviour which could potentially result in suspicions of cheating, plagiarism, misrepresentation of facts and/or participation in an offence. Academic dishonesty is a serious offence and can result in suspension or expulsion from the University. An important excerpt from the Code of Student Behaviour is appended at the end of this syllabus. Additional information and resources are available through the U of A’s Truth in Education project: http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/TIE/. SPECIALIZED SUPPORT & DISABILITY SERVICES: Students with disabilities or special needs that might interfere with their performance should contact the professor at the beginning of the course with the appropriate documentation. Every effort will be made to accommodate such students, but in all cases prior arrangements must be made to ensure that any special needs can be met in a timely fashion and in such a way that the rest of the class is not put at an unfair disadvantage. Students requiring special support or services should be registered with the office of Specialized Support & Disability Services (SSDS): http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/SSDS/. This is particularly important for students requiring special exam arrangements. Once you have registered with SSDS, it is your responsibility to provide the instructor with a "Letter of Introduction" and, if necessary, an "Exam Instruction & Authorization" form. FOR HELP WITH WRITING AND LEARNING SKILLS, CONSULT THE ACADEMIC SUPPORT SERVICES: http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/academicsupport/. Feeling Overwhelmed? (In need of student, social, financial or security services?): The Student Distress Centre is there to listen, offer support, supply information and provide services: Call: 492-HELP (492-4357) Drop in: 030-N in the S.U.B. Visit: www.su.ualberta.ca/sdc Chat: http://www.campuscrisischat.com/ COURSE GUIDE The syllabus provides a guide to the topics we will be covering. There is also a course schedule on the website that provides a quick, tabular reference to topics and readings by class session. You should make every effort to complete your readings before the class in which they will be discussed. Please note that, while I will try to keep us on schedule, there may be some variation in the pace of the course depending on class discussions, scheduling of guest speakers, or unforeseen events. We might get a bit ahead of schedule at some points in the term, or a bit behind schedule. If you attend class regularly you will know where we are in terms of readings. 4 CP means that you will find this reading in your course package. EA means that you have electronic access to this reading through Rutherford Library. (website) means that you can download the reading from the course website. NOTE: Links to readings have been imbedded in the course schedule (website) to help you to find the materials easily. http://polsci333.pbworks.com/ Sept 6 Introduction to the course Sept 11-20 Political Ecology: Global and Local Sept 11-13 Screening of Darwin’s Nightmare (film by Hubert Sauper, 2004, 106 mins.). Read Prof. Adkin’s notes on this film (course website), and look at the film’s website: http://www.darwinsnightmare.com/index.htm. Sept 18 What is political ecology? (lecture and class discussion) In the views of these authors, what is the relationship between globalization and poverty? What has “development” meant in social and ecological terms for majorities in the global South? What kind of development do these authors advocate, and what are its implications for the Global North? Required readings: Philip McMichael, “Feeding the World: Agriculture, Development, and Ecology,” in L. Panitch and C. Leys, eds. Coming to Terms with Nature, pp. 170-194. Vandana Shiva, “Poverty and Globalization.” BBC Reith Lecture 2000; online at http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/events/reith_2000/lecture5.stm EA (c. 12 pp. not including the Q & A session) Sept. 20-25 Environmental Discourses: An Introduction What is “discourse analysis” and why do we do it? What are Dryzek’s categories? Required readings: Dryzek, “Making sense of earth’s politics: a discourse approach,” 3-23. Recommended: Jamie Peck, “Neoliberal hurricane: who framed New Orleans?” in Coming to Terms with Nature, pp. 102-129. 5 Discourse Analysis Discourse analysis is used to understand the ways in which actors try to frame what is at stake in a conflict. What are their assumptions about human nature? About a good society? About the appropriate role of the state vis-à-vis the market? How do they try to establish the superiority of their knowledge of the issue? We uncover these assumptions in the language they use, and sometimes in imagery (as in advertising, logos, banners, the staging of events, etc.). How do they marginalize—or exclude altogether—competing claims or alternatives to their preferred interpretations and solutions? Whoever succeeds in establishing the “dominant” interpretation of a conflict/event has greater chances of determining the possible outcomes. For example, a conflict about clear-cut logging may be constructed, discursively, so as to pit loggers and their dependants against environmentalists (a jobs versus the environment trade-off). Or, it might be constructed as a conflict between economic drives for profit maximization and excessive consumption, on one hand, and a local community that wants to ensure sustainable livelihoods, on the other hand. Discourse analysis typically focuses on actors: how do they make sense of, or try to “fix” the meaning of, any issue or question? What strategies do they use? John Dryzek sets out a number of elements of discourse to look for in Politics of the Earth. Sept 27 – Oct 4 Are there global limits to growth? Are there ecological limits to human economic and population growth, or can human ingenuity conquer all? Should we look to science and technology to solve all environmental, social, and resource scarcity problems? What Dryzek labels “survivalism” is one (early) variant of the belief that there are “limits to growth,” in terms of both human population growth and human use of the earth’s resources. Ecologists generally believe that surpassing the earth’s ecosystems’ capacities to reproduce themselves will have unpredictable and uncontrollable consequences for humans and other species. While humans may not cease to exist as a species, they will be radically affected by “overshoot”-- some populations more negatively than others, depending upon their location and access to resources. In contemporary climate change debates, what terms are used to label those who think that global warming is real and harmful, on one hand, and those who think that the problem is not real, or is exaggerated, on the other hand? Is the concept of ecological footprint useful? Influential? Required readings: John Dryzek, “Looming Tragedy: Survivalism,” pp. 27-50. Herman Daly, "Economics in a full world," Scientific American September 2005, pp. 100107. (website) M. Wackernagel and William Rees, “Ecological footprints for beginners,” 7-16, 28-30, in Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees, Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human 6 Impact on the Earth (New Society Pubs., 2006). CP Hugh Mackenzie, Hans Messinger, and Rick Smith, Size Matters: Canada’s Ecological Footprint, by Income. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, June 2008, http://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/size-matters. Global Footprint Network, “Ecological Footprint and Biocapacity, 2005,” October 26, 2008, http://www.footprintnetwork.org/en/index.php/GFN/page/footprint_for_nations/. OCT 4 FIRST FOCUS PAPER DUE TODAY IN CLASS Net Primary Product of Photosynthesis (NPP) “NPP is the amount of energy left after subtracting the respiration of primary producers (mostly plants) from the total amount of energy (mostly solar) that is fixed biologically. NPP provides the basis for maintenance, growth, and reproduction of all heterotrophs (consumers and decomposers); it is the total food resource on Earth. We are interested in human use of this resource both for what it implies for other species, which must use the leftovers, and for what it could imply about limits to the number of people the earth can support” (Vitousek, P. M. et al. (1986). "Human Appropriation of the Products of Photosynthesis." BioScience vol. 36, p. 358373.) For an article by Helmut Haberl et al., explaining the concepts of NPP, see: http://www.eoearth.org/article/Global_human_appropriation_of_net_primary_production_ (HANPP) For a more technical version, see: Helmut Haberl, et al. "Quantifying and mapping the human appropriation of net primary production in earth’s terrestrial ecosystems," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA vol. 104, no. 31 (July 31, 2007): 12942-12947. Available online at: http://www.pnas.org/content/104/31/12942/suppl/DC1 or http://www.davidzaks.com/haberl2007.pdf. Oct 9 Peak Oil and the End of Growth What is “peak oil” and what does it mean for global capitalism? Where do Altvater and Buck disagree, and whose arguments do you find more persuasive? Why? Required readings Elmar Altvater, “The social and natural environment of fossil capitalism,” in Coming to Terms with Nature, pp. 37-59. Daniel Buck, “The ecological question: can capitalism prevail?” in Coming to Terms with Nature, pp. 60-71. 7 The End of Growth? A pioneer of ecological economics, Herman E. Daly began publishing about ecological limits to growth in the 1970s. Among his works are Steady-State Economics (1977), Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development (1996), and Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed. (2011). In recent years a new crop of books has appeared, proclaiming “the end of growth.” These often focus on the implications of “peak oil,” and call for economic restructuring along lines similar to those advocated by Daly decades ago. See, for example: John Michael Greer, The Wealth of Nature: Economics as if Survival Mattered (2011); Richard Heinberg, The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (2011); Jeff Rubin, Why Your World Is About To Get A Whole Lot Smaller (Oil and the End of Globalization) (2009), and; Jeff Rubin, The End of Growth (2011). Peak Oil Peak oil is the point in time at which the production of conventional oil by a country (or globally) will reach a maximum (will plateau) and thereafter decline. This peak was reached in the United States in 1971, and is predicted to occur at the global level between 2005 and 2020. For a 2005 report on peak oil by the United States Department of Energy, see: “Peaking of World Oil Production: Impacts, Mitigation, & Risk Management,” by Robert L. Hirsch, SAIC, Project Leader, Roger Bezdek, MISI, Robert Wendling, MISI. United States Department of Energy, February 2005. George Monbiot also interviewed the chief economist of the International Energy Association (IEA), December 2008: http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/dec/15/oil-peakenergy-iea. The Post Carbon Institute in the United States publishes reports and articles on peak oil. See http://www.energybulletin.net/. In his recent book, Why Your World Is about to Get a Whole Lot Smaller, Jeff Rubin discusses the evidence that we are now “scraping the bottom of the barrel” of global oil reserves in the form of “unconventional” oil (tar sands, deep water, shale). October 11 Growth forever: Prometheanism and its critics What are the key arguments, or claims, of the “Prometheans”? Do you share their faith in the capacity of markets and technologies to dissolve ecological limits to growth? For class discussion: can you think of some examples of Promethean thinking in contemporary political discourse? 8 Required readings: John Dryzek, “Growth Forever: the Promethean Response,” 51-71. Paul Wapner, “Sacrifice in an Age of Comfort,” 33-60, in Michael Maniates and John M. Meyer, eds., The Environmental Politics of Sacrifice (Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2010). [book available electronically through the U of A library] OCT 16 FIRST PARTICIPATION SELF-EVALUATION DUE IN CLASS Nuclear Dynamite (film dir. by Gary Marcuse, 2000, 52 mins., NFB/Face to Face Media). Oct 18-23 Prometheanism, Science, Gender: The Death of Nature Identify the key arguments here, as well as Merchant’s methodology. What are the implications of her analysis for the contemporary crisis of nature? Does a non-mechanistic, non-patriarchal conception of nature survive anywhere today? Do we need one? Required readings: Carolyn Merchant, “Introduction” (pp. xix-xxiv) and chs. 1 and 7 in The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution (San Francisco: Harper & Row Pubs., 1980). Naomi Klein, “Gulf Oil Spill: A Hole in the World,” The Guardian June 19, 2010, http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguardian/2010/jun/19/naomi-klein-gulf-oil-spill. October 25 Deep Ecology and Ecocentrism How do these approaches differ from the market liberals’ views of human nature, human needs, and nature? Where are they rooted? What are they up against? Required readings: Bill Devall and George Sessions, “Deep ecology,” excerpt from Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered (Salt Lake City: Gibbs M. Smith, Inc.; Peregrine Smith Books, 1985): 65-73. CP Robyn Eckersley, "Ecocentric Discourses: Problems and Prospects for Nature Advocacy" (Tamkang Review 34, 3-4 (Spring-Summer 2004), 155-86.2004). (website) Recommended: Arne Naess, “The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement: a summary.” Inquiry 16 (1973), 95-100. (website) 9 OCT 30 2ND FOCUS PAPER DUE IN CLASS October 30- November 6 Environmental Racism/ Environmental Justice Where do the terms “environmental racism” and “environmental justice” come from and what do they mean? How are they being used in different contexts? Are they effective, politically? Oct 30 Film: Amnesty International UK documentary film Our Land, My People: The Struggle of the Lubicon Cree (2009, 30 mins.) and, possibly, another short film, depending on where we are in covering course material. Required readings: Course notes notes on the Lubicon.docx. (website) [for background, also see Amnesty International, “Justice for the Lubicon Cree,” http://www.amnesty.ca/topics/indigenous-peoples/?SubTopicID=39, updated 24 August 2012. Robert D. Bullard, “Environmental Justice in the 21st Century.” (c. 21 pp.) Access online at www.ejrc.cau.edu/ejinthe21century.htm . EA Nicola Bullard, “Climate debt as a subversive political strategy,” Committee for the Abolition of Third World Debt, 22 April 2010, http://cadtm.org/Climate-debt-as-a-subversive. South-South Summit on Climate Justice and Finance, “Cancun Declaration,” 12 January 2011, http://cadtm.org/Cancun-Declaration. Recommended (for those who can read Spanish): Acción Ecológica, “Deuda Ecológica,” http://www.accionecologica.org/deuda-ecologica. Amnesty International, “Pushed to the Edge: The Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada,” http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR20/002/2009/en. Winona LaDuke, “Reclaiming our Native Earth,” Earth Island Journal (Spring 2000). November 8 Indigenous Perspectives on Human-Nature Relations What are the relationships between colonialism and the crisis of nature? How do these perspectives speak to other environmental discourses, and where are they being heard (or not heard)? Required readings: Winona LaDuke, All Our Relations, 1-6 and 197-200. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1999. CP Ardith Walkem, “The Land is Dry: Indigenous Peoples, Water, and Environmental Justice,” 303-320. In Karen Bakker, ed. Eau Canada: The Future of Canada’s Water. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007. EA 10 Mary Arquette, Maxine Cole, and the Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment, “Restoring our relationships for the future,” 332-350. In In the Way of Development: Indigenous Peoples, Life Projects, and Globalization. Eds. Mario Blaser et al. Zed Books, 2004. EA November 15 -20 Market-based approaches to ecological sustainability A continuum of positions exists with regard to letting the market regulate human use of the environment. Some economists and politicians believe, like Anderson and Leal, that commodifying everything is the answer. Others support “market-based” approaches to environmental policy because they think it is the only politically feasible way of improving environmental performance. It is, of course, possible to support a mix of state and market forms of regulation, e.g., government monitoring and enforcement of environmental laws combined with market incentives for economic restructuring. Policy approaches toward the problem of greenhouse gas emissions reduction allow us to examine the broad issues with regard to market-based versus alternative approaches to the environmental regulation of capitalist economies. Required readings John Dryzek, “Leave it to the market: economic rationalism,” 121-142. Joseph E. Aldy and Robert N. Stavins, “The Promise and Problems of Pricing Carbon: Theory and Experience,” Journal of Environment and Development vol. 21, no. 2 (2012), pp. 152180. (website) Recommended Terry L. Anderson, and Donald R. Leal, Free Market Environmentalism, revised ed. (London: Palgrave, 2001), 9-26. EA http://books.google.ca/books?id=roxpZ6wZQsEC&pg=PA9&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v= onepage&q&f=false] Michele Betsill and Matthew J. Hoffmann, “The contours of `cap and trade’: The evolution of emissions trading systems for greenhouse gases,” Review of Policy Research vol. 28, no. 1 (2011), pp. 83-106. (website) NOV 20 FINAL FOCUS PAPER DUE IN CLASS November 22-27 Critics of Market-Based Approaches What do you think of the arguments made by the “free market environmentalists” and the more mainstream neoclassical economists? Some the general questions to consider are: Is further commodification of nature the way to resolve environmental crises? Is a (state-based) regulatory approach necessary? What are the appropriate roles for markets, states, and citizens in dealing with problems such as pollution, climate change, or water scarcity? Is 11 selling “permits to pollute” ethical? If not, is it necessary? Why? Required Readings: Robert Goodin, “Selling Environmental Indulgences,” Kyklos 47 (1994), 573-96. (website) Shane Gunster, “Self-Interest, Sacrifice, and Climate Change: (Re-)Framing the British Columbia Carbon Tax,” in Michael Maniates and John M. Meyer, eds., The Environmental Politics of Sacrifice (MIT Press, 2010): 187-216. (e-book, U of A library) Heather Rogers, “Garbage capitalism’s green commerce,” in Leo Panitch and Colin Leys, eds., Coming to Terms with Nature, pp. 231-253. Kathleen McAfee, "The Contradictory Logic of Global Ecosystem Services Markets,” Development and Change vol. 43 issue no. 1 (January 2012): 105-131. (website) Recommended Michelle Chan, “A ruse of Olympic proportions: BP’s carbon offsets,” Friends of the Earth Blog, August 6, 2012, http://www.foe.org/news/blog/2012-08-a-ruse-of-olympic-proportions-bps-carbon-offsets. Debating Carbon Markets Arguments about the adequacy of market-based approaches to environmental problems are being played out in current policy debates about the reduction of GHGs. The predominant market-based approach taken by governments so far to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) has been to create markets for the buying and selling of emission credits (e.g., the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme, the world’s biggest carbon market). There have been many critical analyses of existing emissions-trading schemes (trading in emission allocations, allowances, or permits), including the Clean Development Mechanism and Joint Implementation Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol. For a comprehensive assessment of current approaches to GHG reduction, read Oliver Tickell, Kyoto2: How to Manage the Global Greenhouse (London; New York: Zed Books, 2008). More sources are available on the course website. NOV 27 RESEARCH ESSAY DUE IN CLASS November 29-December 4 Ecological Citizenship and Ecological Democracy What is meant by these terms? How do they compare to liberal democracy or social democracy? How can individuals be ecological citizens? Can institutions be ecological citizens? Required readings John Dryzek, Politics of the Earth, pp. Jason Found and R. Michael M’Gonigle, “Beyond the reach of democracy? The university and institutional citizenship,” in Environmental Conflict and Democracy in Canada, 191-208. 12 Ed. Laurie E. Adkin. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009. CP Yael Parag and Deborah Strickland, “Personal Carbon Trading: A Radical Policy Option for Reducing Emissions from the Domestic Sector,” Environment vol. 53, issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2011): 29-37. (website) DEC 4 2ND PARTICIPATION SELF-EVALUATION DUE IN CLASS 13 GUIDELINES FOR READING, CLASS DISCUSSION , AND, GENERALLY, HOW TO DO WELL IN THIS COURSE Reading: The syllabus poses questions regarding the readings. Use these questions to look for important points as you read. Also take into account the general questions that I list here (below). Take notes. Have your readings done by the beginning of the section in which there will be lectures and class discussion about them. • Each approach makes certain assumptions about human nature, the “natural” dynamics of human societies, and the possibilities for organizing the relationships among humans and between humans and nature. In each case, try to identify what these assumptions are. Also, for each approach, ask yourself the following questions: What are the key arguments of this author? How does s/he understand the causes of the environmental crisis? Given this interpretation, what solutions are implied? What needs to be changed, and how, in order to create an ecologically sustainable human existence? What struggles will this entail? Which social or political actors might take the lead in these struggles? How important is the goal of reducing inequalities and poverty within human societies for this approach? How are economic and social relationships related to (part of the explanation for) environmental problems? • As new perspectives are introduced, try to relate these to one another. For example, on what grounds do eco-socialists criticize the market liberalism approach? What might eco-feminism have to say about Prometheanism? What does the environmental justice approach take into account which may have been missing from other approaches? Participation: • Don’t miss classes. If you are ill, or have to be away for exceptional reasons, let me know so that I can note this with regard to your participation grade. • Arrive on time and do not leave before the class period ends. Do not start packing up your things before the class is over. Do not walk in and out of the room to answer calls on your cell phone. Do not read your facebook messages during class. You get the picture: don’t disrupt the class, and show respect for others. • In class discussion, demonstrate a knowledge of the readings, keep on subject, raise good questions, and interact with others. You are addressing not only the professor, but also other class participants. Listen to others respectfully and try to respond to their points. Written Assignments: Carefully read the guidelines that I have provided. Come to see me if you have any questions. Use my office hours! 14 WRITING GUIDELINES You must use an accepted essay-writing manual for the social sciences. The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) is preferred, but APA is also acceptable. The CMS may be accessed online (http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/home.html), or, you may purchase a style manual. The Turabian et al. manual (see below) provides general guidelines for writing essays, in addition to the style formats for bibliographies, endnotes, and so on. Turabian, Kate, Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams. 2007. A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. Seventh Edition: Chicago Style for Students and Researchers. University of Chicago Press. Provide the complete reference for the style manual used on the title page of your essay. (Do not include the manual reference in your bibliography or list of references.) Failure to use a style manual or to proofread your essay for grammatical errors, as well as inadequate research, will negatively affect your grade. Note that the Arts Faculty requires instructors to “take into consideration the quality of expression [in] assessing the written work of students and to refuse to accept work that is markedly deficient in the mechanics of composition.” Endnote, footnote, or referencing styles are all acceptable, but you must choose and use only ONE. (References are preferred.) Your essay should be type-written and double-spaced, with font no smaller than this (12 pt). The pages should have one-inch margins. Make sure your pages are numbered. You may use internet publications, but these should be correctly cited (so that sources may be relocated by other researchers). You should also provide the date on which you accessed the publication online. For detailed instructions on citing electronic sources, consult your style manual. Printed copies of the essays are to be handed in at the beginning of the November 27th class. Documentation and Writing There are good reasons for using correct, standard styles for punctuation and documentation in your essay; these include clarity and accuracy in identifying the sources of any factual statements or claims you make, and ready comprehension of your writing by the readers. A major problem area is the use of quotations; consult a style guide for the correct practices. Whether you use a referencing style, footnotes, or endnotes, learn an accepted documentation style and use it consistently. The same rule applies for your bibliography or list of references. Many common practices such as paraphrasing, or failing to clearly identify the source of arguments used in an essay, border on plagiarism and should be avoided. If you have any doubts concerning the correct way to use or to credit sources, the correct use of footnotes, and so on, 15 please consult your writer's manual. If you still have questions, talk to your instructor. The penalties for submitting plagiarized work are detailed in the Faculty of Arts statement appended to your course syllabus. It is perfectly acceptable to write in the first person. Evaluation Criteria Does the essay demonstrate a good understanding of the problem under investigation, and of the arguments which have been advanced by the authors whose work addresses this problem? Does the essay demonstrate an ability to develop a coherent position, or argument, regarding the question or problem at hand? This may take the form of critical review of the arguments presented in a particular literature. An outstanding paper will offer some original insights regarding the theoretical problem or question addressed, and will give evidence of careful research. Does the essay demonstrate good writing skills? These include: a coherent structure and presentation of material, clarity of expression, excellent grammar, spelling, and correct use of sources. Of course, creativity is greatly encouraged! Does the essay demonstrate sufficient research to locate sources which are relevant, important, and reasonably up-to-date? Has a reasonable search been made of scholarly journals and other materials related to the area of research? Is there an overly-heavy reliance on only one or two sources, rather than a wide sampling of different perspectives on the subject which have then been subjected to critical examination? FOCUS PAPERS For each paper, choose a question from the syllabus, or construct your own (related to a course reading) and discuss it with the instructor. You must submit a minimum of three papers. You may submit as many as five, and I will take the “best three” for your grade. All will be graded. You will get maximum feedback on the first paper you submit. Thereafter, I will expect you to make improvements based on my corrections and comments, and will provide less detailed feedback on successive papers. Paper Options (Choose a paper question from 3 different topic groups) #1 Political Ecology Darwin’s Nightmare McMichael, Feeding the World Shiva, Poverty and Globalization #3 Limits to Growth Wackernagel and Rees, Ecological Footprints Mackenzie et al., Size Matters Daly, Economics in a Full World #2 Discourse Analysis Peck, Who Framed Hurricane Katrina? #4 Peak Oil and Capitalism Altvater, Social and Natural Environment Buck, The ecological question Rubin, Why Your World is About To Get a Whole Lot Smaller (treat this as a book review) 16 #5 Prometheanism Wapner, Sacrifice in an Age of Comfort # 9 Market-Based Approaches Aldy and Stavins, Promise and Problems Goodin, Selling environmental indulgences Gunster, Self-interest, sacrifice, climate change Rogers, Garbage capitalism Kathleen McAfee, Contradictory Logic Anderson and Leal, Free Market Environmentalism Betsill and Hoffman, The contours of cap and trade #6 Patriarchy and the Crisis of Nature Merchant, Death of Nature #7 Deep Ecology and Ecocentrism Devall and Sessions, Deep Ecology Eckersley, Ecocentric Discourses Naess, The Shallow and the Deep #8 Indigenous Perspectives Arquette et al., Restoring our relationships LaDuke, All our Relations Walkem, The land is dry #10 Ecological Citizenship and Democracy Found & M’Gonigle, Beyond the reach? Parag & Strickland, Personal Carbon Trading GUIDELINES FOR FOCUS PAPERS1 The challenge of writing a focus paper is to state and defend an interesting critical idea in only three pages. This is tough. In a paper of eight or twelve or twenty pages you can meander around some, engage in a bit of gratuitous exposition, and get away with some vagueness in one part of the paper so long as you clear it up in another. Given a 3-page limit, though, you have to cut right to the chase: state a critical thesis, succinctly lay out the relevant parts of the reading in question, and support your critical thesis in a way that might persuade an intelligent rival. This is an effective exercise for honing skills in analysis and writing. If you can learn to write good short papers (and the course is designed so that you can give yourself some practice before any given paper has to count toward your grade), you’ll be in a much better position to write longer papers well. So please read the following pointers, but also be sure to allow for a learning curve in writing these; write some early enough in the term that you can do a few for practice before they start counting towards your mark. These guidelines are adapted, largely vertbatim, from Professor David Kahane’s “Writing ‘working papers’” (included on his syllabus for Phil 368 (Spring 2004) University of Alberta), with his permission. 1 17 To write a good focus paper…. Take a position on an interesting question from one of the readings, or address a question from the syllabus. A good focus paper will take up an interesting question related to the reading. This means first, that it’s something that intelligent people could disagree on; if you can’t imagine smart people disagreeing on the answer to the question, you’re arguing for the obvious—which is uninteresting. Second, an interesting question is one where something important hinges on the answer—where different answers would have big implications for the theory, or for policy, or for something else that matters. Tell me why the question is interesting, what people might disagree on, and how the side you take in this argument might really matter. Decide where you stand on the question—this is the position that you will be arguing for in your paper. It’s your thesis. Make sure that you state it clearly, hopefully in the opening lines of the paper. This way the reader knows what you’re going to show. Engage critically with the reading Your focus paper should do something interesting with the argument from the reading (rather than, say, taking some isolated part of the reading as a jumping off point for a two-page statement of your philosophy of life). So make sure that you succinctly lay out the aspect(s) of the reading’s argument that are relevant to the question you’re exploring. Make sure to leave space, though, for your own critical perspective: your critical argument should take up about half of the paper. Structure your argument So you lay out an interesting question, state your thesis, and lay out the relevant aspects of the article. Now you need to argue for your thesis—giving an intelligent rival or an undecided bystander reasons to take your side. Most often, the reading itself will define one of the positions you’re considering on your interesting question. Either you want to argue against some aspect of the reading, or you want to defend some aspect of the reading against an interesting criticism. Either way, make sure that you’re getting the reading right, and that both of the positions you’re considering are ones that a smart person could take. Given that you only have 750 words for the paper, you probably want to lay out just one or two clear reasons for your position. What reasons could you give that would convince someone to accept your thesis? 18 Consider objections You need to be able to anticipate (and write out) the kind of conversation you would have with someone who disagreed with the direction of your argument. Writing objections and responses is a bit like making a clear, step-by-step map of your thinking, and the thinking of the person who is responding to you. What would puzzle a reader? How might they object to your argument? So when you lay out a reason for your position, one of the most powerful things you can then do is to entertain an objection—what would a smart person who disagreed say back to you? Mention this (“a possible criticism of my position is that…”), then show why your argument can survive this objection. Be succinct You can do all this in 750 words, but only if you establish a clear focus, get straight to the point, and cut out all fluff. You should be able to look at every sentence of your paper, even every word of your paper, and say what it’s doing to further your argument. You’ll want to avoid flowery introductions and conclusions, overly complex sentences, and long-winded examples. You’ll also have to limit yourself to just one or two main points, even if there’s tons more that you’d love to say. The most common mistake that good writers make on these papers is trying to do too much—squeezing in three or four or five points where they should have focused on just one or two. Be clear Write as clearly as possible. Avoid jargon, long words, and convoluted sentences. Don’t try to sound sophisticated or ‘academic’: convey what you have to say as explicitly and unambiguously as you can. One way to test the clarity of your sentences is to read them aloud: if a friend or brother or sister or parent were listening, could they follow easily? If not, consider being more succinct and to the point. Keep sentences and paragraphs relatively short. Also, make sure that you define terms and concepts that are central to your answer. And feel free to write in the first person; it saves words and improves clarity. The passive voice is often pretty boring to read. Be charitable Before you agree or disagree with someone’s ideas—whether they belong to the author of the week’s readings or to an imagined critic of the reading—you have to make clear the structure of their argument (or rather, that part of their argument that is relevant to your own). I cannot emphasize this strongly enough: you have to engage carefully with the arguments of authors whose work you use. It is unpersuasive merely to state their conclusions and to agree or dissent on independent grounds. 19 The authors whose work we read in this course are not fools: if your argument depicts them as such, you probably aren’t reading with adequate care. This isn’t to say that you should agree with them; rather, it’s to suggest that you should disagree with the fairest possible representation of their views. If your attribution of a view to an author is likely to be controversial, offer textual evidence for your interpretation. Strong feelings about the subject at hand should motivate you to argue all the more carefully. Sweeping claims and overblown rhetoric weaken your paper: avoid them. There’s no need to go beyond the course readings There is no need to go beyond course readings in researching focus papers. The goal of a focus paper is to help you develop and demonstrate skills in interpreting and critiquing texts, constructing an argument, anticipating objections, and conveying your ideas clearly and succinctly. If you do choose to go beyond the syllabus in researching your paper, be very sure to credit your sources, and don’t let other sources draw you away from demonstrating the skills just outlined. Use quotations and citations sparingly You don’t have space in a three-page paper for many quotes from the text; a focus papers may not include any quotes at all. If you’re saying something about an author’s argument that’s likely to be puzzling or controversial, do be sure to give a page reference so that your reader can see whether they agree with your interpretation—do this by just putting the page number in brackets like this. [99] Only quote the text (writing it out word for word) when you plan to make special use of a passage, or think your interpretation of the passage is likely to be especially controversial. When you quote the text, give a page reference in brackets like this. [99] Use gender-neutral language There is now a commitment in the North American philosophy profession to the non-sexist use of language: you should reflect this in your use of pronouns. Use ‘he’ and ‘man’ when you want to refer to males, or to be true to the sexist language of a text — these terms can no longer be assumed to denote the entire human race. For discussion of the issue and for advice on usage, see the American Philosophical Association guidelines on the non-sexist use of language, which are on the web at: http://www.apa.udel.edu/apa/publications/texts/nonsexist.html Give yourself time to revise Spend time editing successive drafts of your assignment, making your argument as succinct and organized as possible. Be sure to proof-read your final draft: missing words, misspellings, and poor syntax all serve to undermine the reader’s confidence in the thoughtfulness of your argument. Use your spell-checker, but remember that it only makes sure that all the words you’ve used exist — it 20 won’t tell you, for example, if you’ve used “their” when you should have used “there”, or if you’ve misspelled a name. If at all possible, have someone else read over your assignment; it can be useful to see where you lose people, and where definitions or points that seem obvious to you are questionable or opaque to others. Format the paper properly Your paper must be double-spaced, with 1” margins on all sides, and at least a 12-point font. Your paper must be stapled. Your paper must have your name on it! Always keep your own copy of assignments. Don’t Exceed the Word Limit (750 words) It won’t do you any good . . . Avoid Plagiarism The University of Alberta’s Code of Student Behavior (Section 43.3) puts it like this: “No student shall submit the words, ideas, images, or data of another person as his or her own in any academic writing, essay, thesis, research project or assignment in a course or program of study.” Penalties for plagiarism include failure in the assignment, failure in the course, suspension, and expulsion. If you plagiarize there’s a good chance that you’ll get caught; if you get caught, I will have no choice but to report you to the Dean’s office. You have the responsibility to understand what constitutes plagiarism and to avoid it in all its forms. I want you to appreciate that plagiarism, gross or subtle, will not be tolerated in this course. If you are unsure about whether a particular use of sources, manner of footnoting, form of collaboration, etc., might constitute plagiarism, talk to me. 21 RESEARCH ESSAY Choose a topic that allows you to employ both a political economy and a discourse analysis approach to analyze a strategy or policy outcome. You are strongly advised to consult the instructor before finalizing a topic. For example, you could select a governmental environmental policy (or a policy in another area, e.g., fisheries, industry, trade, that has environmental implications), and offer an explanation of why it was adopted by the provincial or national government in question. Identify the key players/interests in the policy-making process, and how they have attempted to shape public opinion and/or government policy. In the Canadian debate on climate change, key players have included business associations, federal and provincial governments, ENGOs, and scientific bodies. They have different understandings of the gravity, sources, and potential consequences of climate change. They also have different views of the appropriate role for the State in regulating greenhouse gas emissions as well as in implementing other measures to conserve energy, develop alternatives, and so on. In this case, you would use documents representing the positions taken by these different actors to identify the key elements of their discursive strategies (factual claims, sources of authority, omissions, emphases, objectives, etc.). Which positions seem to have been most influential, or successful, to date, and in what regard (shaping government policy, informing public opinion)? What resources do they have to advance their particular positions? (These may be monetary, legal, organizational, economic bargaining power, scientific credibility, access to media, access to policy-makers, strategic savvy, or other.) Other topics might be the debates in Alberta regarding the expansion of oil sands exploitation, the use of nuclear power to fuel oil extraction from the tar sands, or land use consultations. You could choose to focus on the discursive strategy of a non-governmental actor, like the industry proponents of the use of nuclear reactors in Alberta, or of one of the pipeline projects. Or, you could analyze the strategy of an environmental organization with regard to a particular campaign or conflict. There are many other possibilities. Remember that the strategy adopted by any actor in a multi-actor conflict is shaped in response to the strategies and resources of other actors. You will therefore have to have some knowledge of the general environment within which a particular actor is operating. You will have to start out with a clearly defined question followed by a good description of the issue or conflict – one that identifies the actors, their interests, and their resources. Here you will need to employ a political-economic analysis. However, the essay should not be purely descriptive. Remember that this is a political analysis, i.e., you are trying to identify the factors or dynamics that shape the outcomes (the policy or strategy adopted). As this is a research essay, you are expected to have thoroughly researched your topic and to have a correctly-formatted bibliography. You should have a minimum of 10 scholarly sources in your bibliography. An “A” essay usually has at least 20 sources. Maximum essay length is 12 pages, plus the bibliography. 22 Participation Self-Evaluation #1* Fill out the form; submit it in class on October 16th. Name __________________________ Classroom Participation 3.0: “Good” participation means showing up for all the classes, being informed and active in group work or general class discussion. To get more than a 3.0, you’d need to be “Very Good” or “Excellent”: not only showing up and participating, but making really good points, helping your small groups to run well, making sure others get a chance to speak, and so on. You probably deserve 2.7 or less if you have missed classes without making arrangements with me; dominated in small groups in ways that prevented others from having a say; repeatedly taken things off topic in small groups or with disruptive interventions in class; and so on. Remember that 2.7 still means “Good”, 1.7-2.3 means “Satisfactory”, and 1.3 means “Poor”. I missed ____ classes in this half of the term. I think that I deserve a ___/4.0 for classroom participation in this half of the term, because: (use reverse side if you wish) Prof’s judgment: ___/4.0 ______________ * Adapted from David Kahane’s participation self-evaluation form for Phil 368 (spring 2004). 23 Participation Self-Evaluation #2* Fill out the form; submit it in class on December 4th. Name __________________________ Classroom Participation 3.0: “Good” participation means showing up for all the classes, being informed and active in group work or general class discussion. To get more than a 3.0, you’d need to be “Very Good” or “Excellent”: not only showing up and participating, but making really good points, helping your small groups to run well, making sure others get a chance to speak, and so on. You probably deserve 2.7 or less if you have missed classes without making arrangements with me; dominated in small groups in ways that prevented others from having a say; repeatedly taken things off topic in small groups or with disruptive interventions in class; and so on. Remember that 2.7 still means “Good”, 1.7-2.3 means “Satisfactory”, and 1.3 means “Poor”. I missed ____ classes in this half of the term. I think that I deserve a ___/4.0 for classroom participation in this half of the term, because: (use reverse side if you wish) Prof’s judgment: ___/4.0 ___________________ * Adapted from David Kahane’s participation self-evaluation form for Phil 368 (spring 2004). 24