UNIB30004-2014-14-DSD-medical_and_ethical_issues

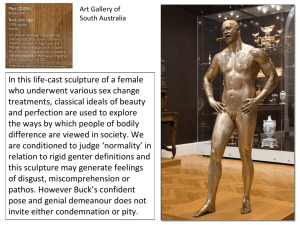

advertisement

UNIB30004 Sex: Science and the Community Disorders of sex development and transsexualism in children Lecture adapted from one given by Dr Jackie Hewitt, RCH, 2011 Baby X Canadian couple decide to allow their children to discover their gender for themselves. • • • No announcement about baby’s sex Names, clothing, hairstyle gender-neutral Questions about child’s gender not answered Is this harmful to the child? Is it a form of abuse? • Biology of disorders • Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH) • 5-Reductase deficiency • Androgen insensitivity (CAIS) • Case studies and ethical issues XX = FEMALE XY = MALE AMH regressed Mullerian Duct Testosterone stimulated Wolffian Duct MD (oviduct and uterus) regressing WD T prostate 5α-reductase DHT external genitalia Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Adrenal Steroids • defective enzymes • adrenals cannot make cortisol • hyperstimulation of adrenals overflow of precursors into androgen pathway Testosterone • enzyme defect fetal adrenal makes androgens • virilisation of XX female fetuses with range of severity clitoral enlargement (masculinised female) labial fusion and penile development (male like) • internal ovaries, oviduct, uterus, vagina (no AMH) 5α-Reductase deficiency XY = MALE AMH regressed Mullerian Duct Testosterone stimulated Wolffian Duct • Production of DHT impaired or absent • XY males feminised external genitals • testes internal • T WD differentiation • MD degenerates T prostate 5α-reductase DHT Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome • Defective androgen receptor. Partial of complete insensitivity CAIS) XY = MALE AMH regressed Mullerian Duct Testosterone stimulated Wolffian Duct T prostate 5α-reductase • XY males feminised external genitals • testes internal • WD regresses • MD degenerates DHT When is gender identity formed? • Core gender identity (Stoller) is the fundamental sense of belonging to one sex • Develops between 18 mo and 3 yrs • Gender labelling - from 18 mo infant is able to label individuals as M or F on external appearance. Gender not seen as fixed. • Gender constancy - by 3yr gender is part of the selfconcept • Gender stability - reached by age 4-5 yr What factors influence gender identity? • Some understanding from children with disorders of sex development (DSD) and gender identity disorder (GID) gender identity dysphoria (DSM-V) • Infant’s interactions with carers • Prenatal exposure to testosterone • Functional androgen receptor • Postnatal exposure of a genetic female to testosterone (e.g NSW-CAH, 17B-HSD) • Genetic factors (twin studies of GID) • Other unknown factors What is sex? Either of the two main categories (male and female) into which humans and most other living things are divided on the basis of their reproductive functions. No encompassing scientific definition. Chromosomal sex Gonadal sex Anatomical sex Brain sex XX XY Ovaries Testes Vagina and uterus Penis and scrotum Female Male Sex, gender identity, gender role and sexual orientation are different. What is sex? Either of the two main categories (male and female) into which humans and most other living things are divided on the basis of their reproductive functions. No encompassing scientific definition. Chromosomal sex Gonadal sex Anatomical sex Brain sex XX XY XX/XY Ovaries Testes Ovotestes Vagina and uterus Penis and scrotum Ambiguous Female Male Neither Sex, gender identity, gender role and sexual orientation are different. DSD and GID • Disorders of sex development (DSD) are congenital conditions where there is atypical development of the chromosomal, gonadal or anatomic sex. • Currently a biological diagnosis. • Disagreement between patients on preferred terminology – intersex, differences of sex development, variations of sex development. • Gender identity disorder (GID) is where an individual has a persistent and profound incongruence between their gender identity and their anatomic sex. • Currently a mental health diagnosis. • Other terminology used – transsexualism, transgender, gender identity dysphoria. Child Z: born in India • Phenotypic female infant with inguinal testes, absent uterus and 46,XY karyotype • Diagnosed as CAIS, recommendation to raise as female • Father (lecturer in Islamic law) rejects medical advice and raises child as male on cultural grounds and to give best chance of economic independence • Father’s arguments: under local Muslim law, a son may 1. Inherit from his father (daughters get half share) 2. Join the priesthood 3. Be employed and be economically independent 4. An infertile woman cannot be offered in marriage 5. Unmarried women are unemployable and are therefore dependent on parents for life 6. IVF not an option Child Z: born in India • At 17, patient returns as young man with sparse beard and pubic hair. • Genitalia now ambiguous – penis has grown • Diagnosis: deficiency of 17α-hydroxylase reduced ability to make testosterone • extra stimulation of testes at puberty testosterone production for partial virilisation Gender “assignment” • A decision made by doctors and parents about sex of rearing; decision about genital surgery follows • Based on a prediction of what the gender identity will be • Uncertainty acknowledged, but influence of carers and environment was thought to be more powerful than influence of hormones RCH data: perspective on diagnosis Bhullar & Hewitt et al. J Ped Adol Gyn 2011. • 199 patients aged 0-10 yrs seen at RCHM 1999-2008 • • • • • 46,XY 54% 46,XX 32% Mixed chromosome DSD (45,X/ 46,XY) 14% Definitive diagnosis reached for 87.5% of 46,XX DSD No definitive diagnosis in 71% of 46,XY DSD • • • • Sex of rearing 46,XY – 92% male, 8% female 46,XX – 98% female, 2% male Mixed chromosomes – 68% male, 32% female Accuracy of gender assignment • 95% accurate in females with CAH • Exceptions often present late or are exposed to androgen for long periods during childhood • Other conditions: most affirm a gender that conforms to their original assigned sex • Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome – 25% of adults unhappy about gender regardless of sex of rearing (but only a few want surgery to change genitalia) • in 5α-reductase deficiency and 17β-HSD deficiency – usually identify as girls when young but have ambiguous genitalia. Greater likelihood of male gender identity after puberty onset. Accuracy of gender assignment • Does early gonadectomy change gender shift? • How great is the risk if feminizing genital surgery (which involves removal of erectile tissues) is undertaken? • Are these surgical procedures ethical if one cannot be certain about the child’s future gender identity? • Is it ethical to raise a child with ambiguous genitalia, especially against the wishes of the parents? Ethical principles for decision making in DSD Gillam, Hewitt & Warne. Horm Res 2010. 1. Minimizing physical risk to the child 2. Minimizing psychosocial risk to the child 3. Preserving potential for fertility 4. Preserving or promoting capacity to have satisfying sexual relations 5. Leaving options open for the future 6. Respecting the parents’ wishes and beliefs Do any of these principles have greater importance in decision-making? Queensland and court involvement in medical decision making • Four cases of DSD • Doctors recommended removal of dysgenetic gonads because of a known risk of cancer and because they might cause unwanted masculine development in a girl • All cases were referred to the Family Court of Australia for a judge to authorize removal of gonads • Created legal precedent redefining ‘special medical procedure’ • The doctors and the hospital were concerned about - Making infertility a certainty, instead of a probability - The risk of being sued if a patient’s affirmed gender identity proved to be different from the assigned sex Why was this a problem? • Taking the cases to court created a legal precedent that is binding on all doctors throughout Australia • Each court case costs approximately $20,000 (in some states this cost will need to be borne by the family) • The court supported the doctors in every case Alternative approaches: • A multi-disciplinary specialist team could have provided a consensus recommendation on the best course of treatment (this is what occurs internationally) • An ethics committee could have analysed the issues and provided valuable advice to the clinicians, without costing any money or creating legal precedent • If legal involvement was required, a children’s tribunal for special medical procedures would provide consistency and expertise, at less individual cost In a hospital in New South Wales • Doctors decide not to recommend genital surgery for any infants • Decisions about surgery are left until the patients are old enough to decide for themselves • But when are they considered competent to make this decision? • Who can give valid consent? The parents? The patient? Or only the court? Gender dysphoria • The sense of discomfort or disease with one’s biological sex and assigned gender role • May be profound and persistent – high risk of self harm, suicide Gender dysphoria in DSD • Distress intensified by having had medical treatment • Some intrinsic gender instability possible (in PAIS gender dysphoria not related to sex of rearing) • Teenager with DSD and gender dysphoria may not talk about it – but behaviour will reveal distress when hormone replacement is given, as physical changes generate revulsion - (e.g. patient with PAIS raised female may request surgical mastectomy and testosterone treatment in adult life, even after living in female role for a long period of time, including marriage to a male) • Parents may deny because of guilt and anxiety (“just a stage”) Screening for GD in DSD • Acknowledge the possibility and allow patient to express their emotions • Say “some people feel ....” • Observe reactions and behaviour, especially when hormonal therapy is being offered • Refer to an experienced mental health professional when GD is suspected • Better still, always involve mental health professional as team member Management of GD in DSD • Psychotherapy. Most patients with GD do not want surgery (different from GID) • Surgical options are poor if genital tissues have been removed; satisfactory reconstruction is very difficult, if not impossible. • Frustration leads to anger and depression (requiring help) • Some patients prefer to live as the other gender, even though they have had genital tissues removed, i.e feeling respected in the affirmed social gender is a positive outcome. Gender identity disorder • A DSM-IV diagnosis, ie classified as a mental disorder (Gender identity dysphoria in DSM-V) • Untreatable by any form of psychotherapy • Many experts consider GID a ‘variation of sexual formation’ in which brain sex and anatomical sex don’t match • Cause unknown • By definition, DSD has been excluded • A small genetic contribution (twin studies) Progression of GID of childhood • Very young children may display interest in what it would be like to be the other sex • An effeminate child in a strongly macho, homophobic culture may be wrongly labelled Differential diagnosis in an adolescent or adult • Transsexual/ transgender – wishes to be identified as the other sex, usually wants surgery • Transvestite • ‘Genderqueer ’ (both sexes, neither sex, fluid) • ‘ Voluntary eunuch ’ – wishes to be sexually neutral, to have sex organs removed but wants no hormone replacement • Other Endocrine treatment of GID - aims • Early intervention to block unwanted pubertal development - relieves gender dysphoria, allows person to get on with life - makes some surgery e.g mastectomies for FTM, unnecessary - prevents voice change and beard growth for MTF patients - allows person to grow up looking consistent with identified gender - hopefully prevents development of unhealthy life style on the ‘fringe ’ of society - links young person to professional help History of hormone treatment of GID in children • GID clinic in the Netherlands found better outcomes for those treated with hormones earlier - commenced paediatric hormone treatment in 1980s. • Guidelines for hormone treatment of children published in Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009, endorsed by ES, LWPES, ESPE, APEG. • Child and adolescent clinics providing hormone treatment in US (NY, Boston, LA, San Francisco, Cleveland, Chicago, Seattle), Scandinavia (Sweden), Europe (Spain, Germany – Frankfurt and Hamburg, Netherlands – Amsterdam and Utrecht), UK (London: research) and Canada (Toronto and Vancouver), NZ. History of hormone treatment of GID in children • Re: Alex, Warne and Paul 2003 • Experience 2003-2011 reported Hewitt et al. MJA 2012 • Correspondence: argument for earlier treatment and more services Hyde MJA 2012, and Gillick competence of older children >16 years Handelsman et al. MJA 2012. • Legal requirement for those <18 unclear re: Gillick • Calls for specialised tribunal Endocrine management of an adolescent with GID • Diagnosis of GID confirmed by two experienced psychiatrists • Endocrinologist’s role: exclude DSD or any other endocrine disorder, examine for pubertal development • Participate in clinical ethics committee review • Prepare reports for court and give evidence Endocrine treatment • Administer court-authorized GnRH analogue when Tanner stage 2-3 has been reached (suppress puberty) • At around age 16, start cross-sex hormone treatment (may need separate authorization from court) • Can stop GnRH analogue when adult doses of testosterone or oestrogen are being given • Monitor development and liaise with psychiatrist, other key people e.g school teachers and counsellor • Refer on to an adult service at age 18 Difficulties encountered • Significant number of patients have associated psychological or developmental problems, e.g Asperger’s syndrome • Family may be stressed • Young people push the boundaries • Court costs substantial for families able to pay • Complex patient + court process = time consuming • Administrative issues such as name and sex on the medical record • Hormone treatment needs to be individualised Risk of ‘regret’ and litigation • Extremely rare in patients showing full picture of severe gender dysphoria after onset of puberty • Risk reduced if follow international guidelines, involve ethics committee, have multidisciplinary team, only treat after full assessment by psychiatrists and have long term mental health follow up GID at RCHM Hewitt et al. MJA 2012. • 41 patients reviewed by psychiatry • 51% peri/post pubertal and reviewed by endocrinology - 2/3 biological males • Behavioural co-morbidity in 25% • Asperger’s syndrome in 15% • Family history homosexuality or gender dysphoria in 1/3 Most patients plan hormone treatment Hewitt et al. MJA 2012 Frequency of referrals is rising Referrals to GID service 2003 - 2011 Hewitt et al. MJA 2012 Summary • Biological basis of DSDs – genes and hormones – CAH; CAIS/PAIS; androgen synthesis defects • • • • Gender identity vs gonadal / anatomical sex Ethics and practicalities of Gender “assignment” Legal issues Gender dysphoria / Gender Identity disorder