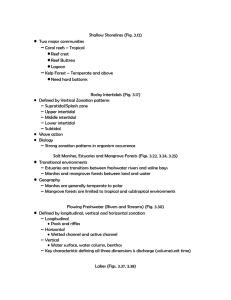

Intertidal Organisms

advertisement

Stephen Jay Gould, Evolution Scientist, Author, Dies at 60 By Richard Pearson Washington Post Staff Writer Tuesday, May 21, 2002; Page B06 Stephen Jay Gould, 60, a Harvard University professor of zoology and geology who became one of the most widely recognized scientists in the world for his graceful, lucid and downright entertaining writings about science, died of lung cancer May 20 at his home in New York. Dr. Gould, a Harvard professor since 1967, gained fame among contemporary scientists as a gifted and controversial student of evolutionary biology, and he conducted notable research in invertebrate paleontology. He became famous for his modification of some of the theories of Charles Darwin. The general public came to know him for his explanations of scientific phenomena that were as understandable as they were authoritative. He wrote more than 20 best-selling books and 300 consecutive monthly essay columns, "This View of Life," for Natural History magazine from 1974 until 2001. His books included "Ever Since Darwin: Reflections in Natural History," "Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History," "Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History," "Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History," "Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes: Further Reflections in Natural History" and "Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life." The intertidal zone is the shoreline between the high and low water mark Emersion presents the biggest challenge to the intertidal community: Water loss = desiccation Temperature fluctuations = can be either too hot or too cold Salinity fluctuations = increased by heating, decreased by rain/runoff Restriction of feeding = most organisms can feed only at high tide Adaptation to these physical challenges produces great diversity in lifestyles: sessile/mobile, deposit/detrital/filter feeding, reproductive strategy, epifaunal/cryptic 1) SPACE LIMITATION: Intertidal populations are usually limited by space, not food or nutrients. 2) VERTICAL ZONATION: Most rocky shores have a distinct pattern of vertical zonation. The upper limit of a zone is often set by physical factors, the lower limit by biological ones (predation, competition for space or food, symbiosis). 3) ECOLOGICAL “SUCCESSION” in the intertidal zone: there is a fairly predictable succession of organisms following a disturbance event. Adaptation to these physical challenges produces great diversity in lifestyles: sessile/mobile, deposit/detrital/filter feeding, reproductive strategy, epifaunal/cryptic 1) SPACE LIMITATION: Intertidal populations are usually limited by space, not food or nutrients. 2) VERTICAL ZONATION: Most rocky shores have a distinct pattern of vertical zonation. The upper limit of a zone is often set by physical factors, the lower limit by biological ones (predation, competition for space or food, symbiosis). 3) ECOLOGICAL “SUCCESSION” in the intertidal zone: there is a fairly predictable succession of organisms following a disturbance event. Adaptation to these physical challenges produces great diversity in lifestyles: sessile/mobile, deposit/detrital/filter feeding, reproductive strategy, epifaunal/cryptic 1) SPACE LIMITATION: Intertidal populations are usually limited by space, not food or nutrients. 2) VERTICAL ZONATION: Most rocky shores have a distinct pattern of vertical zonation. The upper limit of a zone is often set by physical factors, the lower limit by biological ones (predation, competition for space or food, symbiosis). 3) ECOLOGICAL “SUCCESSION” in the intertidal zone: there is a fairly predictable succession of organisms following a disturbance event. Uncovered >50% of the time Covered >75% of the time Rarely uncovered – Spring low tides Littorina keenae, periwinkle Acmaea (limpet) Giant Limpet Giant Limpet Stenoplax (chiton) Chiton - Tonicella lineata. Photo by D. Brumbaugh Balanus (barnacle) Thais preying on Balanus Pollicipes (gooseneck barnacle) Pollicipes (gooseneck barnacle) Nucella emarginata – the dogwhelk Mytilus californianus Mytilus and Haliotis (mussels and abalone) Pisaster Astrometis Anthropleura (sea anemone) Anthropleura (sea anemone) Anthropleura clone Phragmatapoma californiana – colonial tube worm Tube worms Pachygrapsus (shore crab) Pagurus (hermit crab) Pugettia producta – kelp crab Strongylocentrotus purpuratus in holes Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Adaptation to these physical challenges produces great diversity in lifestyles: sessile/mobile, deposit/detrital/filter feeding, reproductive strategy, epifaunal/cryptic 1) SPACE LIMITATION: Intertidal populations are usually limited by space, not food or nutrients. 2) VERTICAL ZONATION: Most rocky shores have a distinct pattern of vertical zonation. The upper limit of a zone is often set by physical factors, the lower limit by biological ones (predation, competition for space or food, symbiosis). 3) ECOLOGICAL “SUCCESSION” in the intertidal zone: there is a fairly predictable succession of organisms following a disturbance event. Flatworm Segmented worm Chama (closed) Chama (dead) Nudibranch Nudibranch Hopkinsia (nudibranch) Gibbonsia montereyensis – crevice sculpin Aplysia Aplysia Aplysia Aplysia Aplysia Aplysia Brittle Star Brittle Star Sea cucumber (Sticapus) Pelvetia Sinus membrane Fucus Fucus distichus Fucus mat Palm seaweed Postelsia Phyllospadix, surfgrass In Science (1995) W.G. Hewatt, Stanford student, 1930