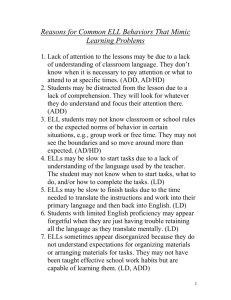

AAHPERD_2013_Sato&Hodge PETE ELL_48x36-Pro

advertisement

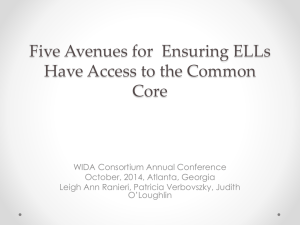

Elementary Physical Education Teachers’ Experiences in Teaching English Language Learners Takahiro Sato, Ph.D., and Samuel R. Hodge, Ph.D. Kent State University and The Ohio State University School of Teaching, Learning & Curriculum Studies & Department of Human Sciences Introduction It is well-known that public schools in the United States (US) have become more diverse (Jackson, 1993). In 2009, McGlynn reported that the enrollment of English Language Leaners (ELLs) over the previous decade had increased at a rate of 57%, compared with an increase of less than 4% of all other students in K-12 public schools in the US. Most teachers believe that speaking an ELL’s native language at home inhibits English language development (Karabenick & Clemens Noda, 2004). It is also troubling that, ELLs are not always served well in public schools (McGlynn, 2009). Ernst-Slavit and Mason (2011) assert that the meaning of technical phases in physical education (PE), such as object control and locomotor skills, are easily understood by most English-speaking elementary-age students, but are much more difficult for their ELLs’ peers. Communication differences may have negative implications for teachers and ELLs in PE settings (Burden, Columna, Hodge, & Martínez de la Vega Mansilla, 2013). During 2006-2007, there were more than 35,000 ELLs enrolled in elementary and secondary public schools in Ohio. This represents a drastic increase of 68% in the last five years and 182% in the last ten years (Ohio Department of Education, 2010). They should receive appropriate instruction, yet this is problematic because “many ELLs spend their school day with local children and students in the classrooms in which many teachers have little or no training in the differential learning and developmental needs” (Herrera & Murray, 2005, p. 6). Measures Descriptive and qualitative data were collected between Fall 2010 through Spring semester 2011. 1. A demographic questionnaire 2. Individual face to face interviews 3. Follow-up E-mail interview 4. This study was supported by Ohio Association of Health Physical Education Recreation and Dance Trustworthiness and Data Analysis Member checking was used to reduce the impact of subjective bias, while establishing trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Patton, 2000). Data coding with NVivo 8 qualitative data analysis software (2010) was used to synthesize and code all the material related to a particular topic or theme. Peer debriefing was used because it is a process of exposing oneself to a distinguished peer in a manner paralleling an analytic session and for the purpose of exploring aspects of inquiry that might remain only implicit with the inquirer’s mind (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Constant comparative analysis was conducted (Merriam, 1998) and involves systematically examining and refining variations in emergent themes. Two approaches to data analysis: (a) within-case analysis, and (b) cross-case analysis (Yin, 2003). Results Purpose and Research Questions The purpose of this study was to describe and explain certain elementary PE teachers’ views about teaching ELLs. The research questions guiding the study were “How do PE teachers’ position themselves in teaching ELLs in elementary schools?’ and “What are PE teachers’ experiences in teaching ELLs in elementary schools?” Conceptual Framework The study was grounded in positioning theory (Harré & van Langenhove, 1999). Positioning theory is a theory of social behavior that explains the fluid patterns of dynamic and changing assignments of rights and duties among groups of social actors (Varela & Harré, 1996). The term positioning means to analyze interpersonal encounters from a discursive view point (Hollway, 1984). Method The research method was descriptive-qualitative, using an in-depth interviewing protocol for data collection (Seidman, 1998). Four major themes emerged from the data: (a) Pedagogical challenges; (b) Traumatized; (c) Irritation, frustrations, & expectations; and (d) Cultural dissonance. Pedagogical Challenges All six teachers regarded their pedagogy as challenged when instructing ELLs in content and concepts (e.g., hopping, skipping) common to PE instruction. Commonly, the ELLs had difficulty speaking, writing, and reading in PE. To aid the Ells’ learning the teachers used various instructional strategies (modeling, demonstrations, hand and body gestures). Language and concepts: Terminology specific to PE content was especially difficult for ELLs to understand, because of linguistic differences. These PE concepts and practices do not match the learning and problem-solving styles and processes of ELLs. Participants had various challenges, including linguistic and cultural barriers in teaching locomotor and non-locomotor skills. Modeling: The ELLs tried to emulate other English speaking students’ motor skills to earn good grades in PE. They did not exhibit independent understandings of the concepts and teachers’ expectations. The research sites for this study were four different school districts located in Northeast Ohio of the United States. Traumatized This theme captures how some students were traumatized in earlier life experiences. From these districts, six PE teachers (Mrs. King, Mrs. Holms, Mrs. Conway, Mrs. Hall, and Mrs. Bowen) were sampled purposively. Noises and Echoes: Several ELLs were afraid of voice echoes, noises, and lights in the gym; the teachers stressed safety in the PE setting before students participated in activities. TEMPLATE DESIGN © 2008 www.PosterPresentations.com Results Establishing Safety: Several ELLs were refugees who previously had life threatening experiences and encountered persecution on account of their race, religion, nationality, or political views. The ELLs sought safe spots during their classes. Those with refugee status were afraid of objects (e.g., balls) moving around them. Participants studied post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and concluded that some ELLs exhibited common signs and symptoms of this condition. Irritation, frustrations, and expectations This theme exposes the fact that the PE teachers were irritated with themselves and ELLs in PE. All six participants were irritated when teaching the ELLs, because the ELLs were failing to meet the teachers’ expectations. Frustration: The teachers positioned themselves as highly qualified teachers who developed their lesson plans to meet state PE standards and benchmarks. They believed that all ELLs must successfully complete their goals and lesson objectives and they were extremely frustrated when the ELLs failed to meet their expectations. Exclusion: Participants were concerned that their ELLs might feel like uninvited guests in PE, because their teachers and/or Englishspeaking schoolmates might marginalize and isolate them. Cultural Dissonance This theme captures the existence of cultural dissonance between the culture of the ELLs and their families, and that of the PE programs and American schools. Gender: The teachers found that parents of male ELLs from Middle Eastern countries prefer male PE teachers over female PE teachers. Parents of female ELLs from the Middle East, prefer that their daughters do not participate in any PE courses, regardless of whether the PE teacher is male or female. The PE teachers were culturally and responsively unable to develop new language discourses that relate to the ELLs’ past language discourses (May, 2008). The PE teachers explained that the ELLs copied the motor skills of English-speaking students from demonstrations (Walqui, 2006). The teachers agreed that they should use scaffolding approaches, such as bridging and re-presenting. Bridging is when the ELLs learn new concepts and languages that build on previous knowledge and understanding (Tharp & Gallimore, 1988). Although the ELLs might not have prior knowledge of motor skills from their own backgrounds, the PE teachers somehow bridged the ELLs’ prior (before joining a PE class in the United States) and current knowledge of PE. The PE teachers had opportunities to teach ELL refugee students who had become physically disabled from war and violence in their native countries. ELLs who experienced war-related trauma had a hard time controlling their reactions to auditory stimuli (e.g., noises, echoes, and bouncing sounds) and exhibited automatic responses to danger (e.g., looking out for danger and never relaxing). Although the ELLs in this study were not officially diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) by medical doctors., the ELLs showed similar or common symptoms (re-experiencing, avoidance, and impaired concentration symptoms) to those listed on PTSD related websites. None of the ELLs received any supportive or appropriate early childhood therapy or intervention at elementary school. PE teachers struggled with the ELLs’ cultural and social needs (Yoon, 2008). ELLs’ actions (e.g., participating or withdrawing) are strongly related to whether teachers implemented the concept of cultural inclusivity. The ELLs were often positioned by teachers as deficient or incompetent, and as uninvited guests and not nurtured in the same spirit of caring at the elementary schools. Fasting: When ELLs began to attend elementary PE, they displayed religious differences that require managing so as to sustain their cultural and traditional beliefs and values during PE. Five of the teachers were both PE teachers and women, so they encountered double jeopardy from the parents of the ELLs and Middle East. There was cultural dissonance; in that, it seemed that some ELLs could not accept female PE teachers as role models because females are forbidden and socially excluded from workplaces in the students’ native countries (Kay, 2006). Discussion Recommendations These six PE teachers positioned their pedagogies as challenged when teaching elementary-aged ELLs. Much of their struggle had to do with language differences, the technical terms used in PE instruction, and cultural and religious differences creating dissonance between the ELLs and their families on the one hand and the culture of the schools on the other hand. The ELLs had culturally and linguistically disparate experiences between the new and past language discourses. The PE teachers sought to address two major challenges of (a) the language of movement patterns and (b) the cultural, social, and linguistic relevance of ELLs in PE (Au, 1998). PE teachers must learn to label academic language discourse items (e.g., skipping, jumping, or dribbling) in both English and the ELLs’ native languages. In order to overcome the ELLs’ war-related trauma, PE teachers should communicate with the parents, friends, and local immigration services and collect information about the ELLs’ war-related trauma. When the PE teachers handle conflicts between the ELLs and their peers in PE, the teachers may need to frame this as both individual and class problems (Lewis, 1996). School districts must aggressively recruit culturally and linguistically diverse PE teachers (Burden, Hodge, O’Bryant, & Harrison, 2004; Burden et al., 2013) and infuse ethnolinguistic approaches into PE teacher training (Burden et al., 2013; Columna, Foley, & Lytle, 2010).