Sylvia Plath

advertisement

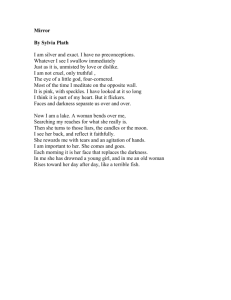

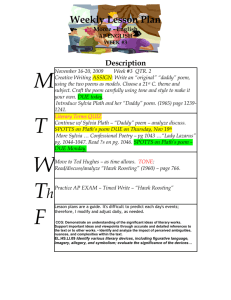

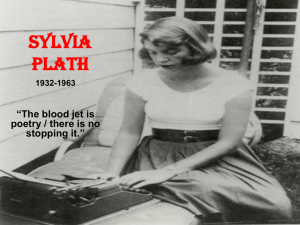

Sylvia Plath A Product of Her Time • Sylvia Plath was a child when the US joined the Second World War and was an adolescent when it ended and dreams of new Utopia became popular. • Generation that came to be in the 1950s suffered from the effects of the Second World War and the “impending doom” cast by future nuclear conflict. This generation did not have the clarity of commitment that marked the previous generation who fought in Spain in WW1. • Sixties were a decade of greater confidence, period where ideas of social harmony were once again possible. Plath was caught between old and new in many ways: “between age of empire and nuclear age, austerity and affluence, elitist cultural ideals and racially integrated, working class ideals.” Poetic Influences •Plath has been called a confessional poet, an extremist poet, a postromantic poet, pre-feminist poet, suicidal poet. Carrier of death wish in everything she wrote. She was also seen as a victim of male brutality: abuse from husband, her mother’s relationship with her father. •Was one of the best-known confessional poets: The confessional poetry of the mid-twentieth century dealt with subject matter that previously had not been openly discussed in American poetry: private experiences with death, trauma, depression and relationships were addressed in this type of poetry, often in an autobiographical manner. Prosody (the use of rhythm and sound in poetry) was still important to Confessional poets. •Plath met Anne Sexton while they were both living in Boston. They became good friend but they were quite competitive with each other. They often had intellectual discussions about death and flirted with ideas of suicide. Sexton committed suicide not long after Plath Poetic Influences… • Beat Poetry: Central elements of "Beat" culture included experimentation with drugs, alternative forms of sexuality, an interest in Middle Eastern culture. Beat Poets represented a departure from the more Metaphysical poetry of George Eliot and followed more romantic models such as Walt Whitman. Early Life • Sylvia Plath was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Otto and Aurelia Plath on October 27, 1932. •Her father was of Polish-German descent and taught at Boston University. His distorted image is common in Plath’s poetry as well as his beekeeping, which serves as a central symbol in Plath’s work. Her mother was Austrian. Warren Plath, Sylvia’s only sibling, was born on April 27, 1935. • Her father died when she was eight of a pulmonary embolism, which was complicated by diabetes. After her father’s death, Plath won many school and local prizes and managed to publish her first short story, “And Summer Will Not Come Again,” in August of 1950, issue of Seventeen, before entering college. Cambridge • Plath did not respond well to pressures building up and became depressed about small failures, ignoring her many triumphs. After ineffective psychiatric treatment, she attempted suicide in the summer of 1953 by hiding herself in her mother’s cellar and taking an overdose of sleeping pills. This confusion of birth and death is a major theme in her novel and poems. Discovered by her mother and brother, she was hospitalized and given electroshock treatments and psychotherapy and was discharged as cured. She returned to Smith for a highly successful final year and received a scholarship to attend Cambridge. Ted Hughes Ted Hughes • At Cambridge, Plath met Ted Hughes, a respected English poet and they got married in 1956. They lived in Cambridge until 1957, when they moved to Boston and Plath taught at Smith. She wanted to continue writing and quit being an academic so in 1959 they moved back to England had a child, Freida, in 1960. • The Colossus, and Other Poems (1960) was published and by the time her song Nicholas was born in 1962, Plath was well at work on The Bell Jar. • Hughes was criticized by some as the cause of Plath’s suicide. His opinion effected her poetry immensely and their separation was the beginning of her “downwards spiral”. After Plath’s death, Hughes did not discuss his life with her at all until the publication of Birthday Letters, a collection of poems that gave an intimate glimpse into Hughes’ and Plath’s relationship. Depression and Suicide • 1962, Hughes and Plath decided to separate and Plath moved to London with her family and she moved into W.B Yeats house, which she took as a good omen. This did not continue when the Bell Jar was published in 1963 and the reviews were not what Plath had hoped. The apartment was also hard to maintain which added to her depression. • As her depression grew, Plath wrote desperately— she scribbled intense poems each morning before the children woke up: “The blood jet is poetry, there’s no stopping it.” On February 11, 1963, she placed towels on the floor to prevent seepage into the other room where the children were sleeping, and she turned on the gas oven. She died at thirty. Plath’s Poetry • Plath’s poems have a common focus on order vs. chaos, control vs. abandon. In its emphasis on death and rebirth, pollution and purification, it touches strings common to many readers. Her images are memorable for their violence and eerie appropriateness. Her exact, verb-dominated descriptions of the natural world and her use of the formal devices of poetry to communicate personal pain mark her work as unique. • Now let’s look at one of Plath’s most well-known poem, Daddy. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6hHjctqSBwM Daddy You do not do, you do not do Any more, black shoe In which I have lived like a foot For thirty years, poor and white, Barely daring to breathe or Achoo. Daddy, I have had to kill you. You died before I had time--Marble-heavy, a bag full of God, Ghastly statue with one gray toe Big as a Frisco seal And a head in the freakish Atlantic Where it pours bean green over blue In the waters off the beautiful Nauset. I used to pray to recover you. Ach, du. Daddy In the German tongue, in the Polish town Scraped flat by the roller Of wars, wars, wars. But the name of the town is common. My Polack friend Says there are a dozen or two. So I never could tell where you Put your foot, your root, I never could talk to you. The tongue stuck in my jaw. It stuck in a barb wire snare. Ich, ich, ich, ich, I could hardly speak. I thought every German was you. And the language obscene Daddy An engine, an engine, Chuffing me off like a Jew. A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen. I began to talk like a Jew. I think I may well be a Jew. The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna Are not very pure or true. With my gypsy ancestress and my weird luck And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack I may be a bit of a Jew. I have always been sacred of you, With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo. And your neat mustache And your Aryan eye, bright blue. Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You---- Daddy Not God but a swastika So black no sky could squeak through. Every woman adores a Fascist, The boot in the face, the brute Brute heart of a brute like you. You stand at the blackboard, daddy, In the picture I have of you, A cleft in your chin instead of your foot But no less a devil for that, no not Any less the black man who Bit my pretty red heart in two. I was ten when they buried you. At twenty I tried to die And get back, back, back to you. I thought even the bones would do. Daddy But they pulled me out of the sack, And they stuck me together with glue. And then I knew what to do. I made a model of you, A man in black with a Meinkampf look And a love of the rack and the screw. And I said I do, I do. So daddy, I'm finally through. The black telephone's off at the root, The voices just can't worm through. Daddy If I've killed one man, I've killed two--The vampire who said he was you And drank my blood for a year, Seven years, if you want to know. Daddy, you can lie back now. There's a stake in your fat black heart And the villagers never liked you. They are dancing and stamping on you. They always knew it was you. Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I'm through. Analysis of Daddy * format of a power point may not be most conducive to discussion and analysis. Just go with it! • • • • • As Plath’s poetry matured, she was less concerned with end rhyme which made it more powerful. The one exception to the rule is “Daddy”. Within convention, it still maintains its immense power. As with other poems such as Lady Lazarus, the speaker’s voice is one of a vengeful woman. Rhythm is anapestic trimeter (three anapests, nine syllables) with many irregularities: The sound “oo” which is included in no particular older, concludes at least one line in each 5 line stanza. Except for one exception. Daddy in this way has clear connections with a nursery rhyme, very sinister: ironic with subject matter. This is her most blatant confrontation with the “daddy” issue that she dealt with her whole life and career. The use of the nursery rhyme form gives readers a sense that Plath still sees herself as a child compared to her father. Separated from the rest of her poetry by the innate intensity but also ease of composition. Previously she had written with a thesaurus, meticulously, but now she just scribbled them down which added to the more intense style of her later poetry. Analysis of Daddy • • • • Plath on using images of concentration camps and Nazis in her poetry: “In particular my background is, may I say, German and Austrian. On one side I am first generation American, on one side I am second generation German and Austrian, and so my concern with concentration camps and so on is uniquely intense. And then, again, I'm rather a political person as well, so I suppose that's part of what it comes from.” Throughout the poem, she makes references to her father as a Nazi: “In the German tongue, in the Polish town “, “Meinkampf”. She makes references to herself as a Jew and her German father as a Nazi, to represent the oppression and “inner war” she felt. – “Made a model of you”– dual-meaning, her father influenced how she viewed men as a whole but also, as a model, she would have been inclined to look up to him as an example. – She refers to Otto Plath as “daddy” as opposed to “father”, which adds to the nursery-rhyme quality of the poem but also adds a mocking tone to the poem. The regular form gives her more control over something she felt she did not have control over. The real power comes from relation with sense and structure. Experimentation with sound is obvious. A common characteristic of poem’s from her collection, Ariel, was the use of stark, shocking imagery. Analysis of Daddy • • • • • • Daddy is an excellent example of the confessional poetry style: sing song quality and allusions to Holocaust give reader insight into the relationship with her father. Very accusatory, repetition of the word “you” Incredibly descriptive, jarring imagery: “In which I have lived like a foot…” gives an image of the entrapment and oppression she felt, “Bit my pretty red heart in two…”, “A stake in your fat black heart”, “The vampire who said he was you, and drank my blood for a year.”(blood and bloodshed is a common image, to emphasize the destructive effect Otto Plath had on Sylvia. ) The vampire she discusses refers to her husband Ted Hughes, to whom she was married for seven years. The vampire image relates to her father and husband, metaphorically sucking the life out of her. First twelve stanzas of the poem illustrate Plath’s father as a character and emphasize her negative image of him. Use real experiences as well as archetypal memories. “I was ten when they buried you. At twenty I tried to die” It is a purgation of Plath’s father’s influence from her memory. “Daddy, Daddy you bastard I’m through.” It is a final dismissal of her father’s influence and the short, powerful sentiment is very effective in illustrating Plath’s emotions. Her Legacy • Advanced development of Confessional Poetry. • Since her death, Plath’s poetry has become incredibly popular and widely studied. Bibliographic Information Blei, Norbert. Sylvia Plath. Web. 15 October 2011. <http://poetrydispatch.wordpress.com/2009/05/06/sylvia-plath-anne-sextonthe-art-the-artists-of-self-destruction-no-1/> Bloom, Harold. Sylvia Plath Updated Ed. New York : Bloom's Literary Criticism, 2007. Print. Brennan, Claire. The Poetry of Sylvia Plath. New York : Columbia University Press, 1999. Print. Gill, Jo. Cambridge Companion to Sylvia Plath. Cambridge, UK ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2006. Print. “Sylvia Plath.” Literary Reference Centre. Web. 15 October 2011. Wagner-Martin. Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life. New York : Palgrave, 2003. Print. “Plath’s Daddy”. Web. 16 October 2011. <http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/plath/daddy.htm> Bibliographic Information: Images Plath, Sylvia. Photograph. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 10 October 2011. <http://school.eb.com/eb/art-16673> Sylvia Plath. Web. 11 October 2011. <http://www.counter-currents.com/2010/11/sylvia-plath-stasis-in-darkness/> Sylvia Plath. Web. 12 October 2011. <http://www.nanogirl.com/poetry/plath.html> Plath. Web. 12 October 2011. <http://i12bent.tumblr.com/post/225284264/sylvia-plath-young-gifted-and-almost-happy> Plath Self-Portrait. Web. 10 October 2011. <http://i12bent.tumblr.com/post/225284264/sylvia-plath-young-gifted-and-almost-happy> Hughes and Plath. Web. 11 October 2011. <http://niklasblog.com/?p=5590> Plath in Office. Web. 11 October 2011. <http://www.sylviaplathforum.com/2.html> Gwyneth Paltrow: Sylvia. Web. 10 October 2011. <http://www.sylviaplathforum.com/455.html> Plath and Hughes. Web. 11 October 2011. <http://arloshelving.com/aquarian-sylvia-plath-and-poetry/>