File

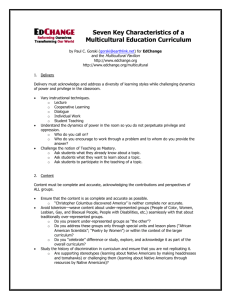

advertisement

Delpit, L. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people's children. Harvard Educational Review, 58(3), 280-298. Summary Centers on the belief that good teaching practices of teachers of all colors typically incorporate a range of pedagogical orientations. Differing perspectives on the debate between “skills” versus “process” approaches can lead to alienation and miscommunication, resulting in a silenced dialogue between educators of color and white educators. Teacher cannot be the only expert in the classroom; both student and teacher are experts at what they know best. Adopting direct instruction is not appropriate; instruction must be related to real purposes and everyday lives of students. Connections to Practice Students need to be taught the appropriate codes (rules of power) needed to successfully participate in dominant society, not through force, but through meaningful learning partnerships in which the teacher’s knowledge is used as a resource as well as the necessary acknowledgement of students own “expert” knowledge. In addition, students need to learn about the arbitrariness of those codes and the power relationships they represent. Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Curriculum Studies Reader. 150158. NY: Routledge. Summary There is transformative power in dialogue if dialoguers both act and reflect on their words. Dialogue cannot exist without (a): Love - an act of commitment to the causes of the world and others, which cannot exist in the presence of domination, (b): Humilityunderstanding that one person is not more valuable than another, (c): Faith in the power of others to engage in the (re)creation of the world Authentic education involves teachers and students learning together through dialogue with one another. Students and teachers need to be able to voice for themselves their experiences with the world, allowing all dialoguers to learn and transform the world around them Connections to Practice Educators should allow for students to engage in dialogue with them in determining not only what gets taught, but what their unique experiences and interpretations of the material might be Educators and students should understand the power that comes with dialogue, and that such is power is not a privilege for some but a right for all. hooks, b. (1994). Embracing change: Teaching in a multicultural world. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. 35-44. NY: Routledge. Summary Change needs to occur in pedagogical practices that allows for our classrooms to be effectively multicultural and transformative of thought There has to be a space in which educators can voice their fears, practices, and methodology surrounding creating multicultural education. It is not enough to want to include study of “marginal” groups and thinkers and the work of “marginal” voices and perspectives. Classroom is a democratic setting: space in which everyone feels a responsibility to participate in dialogue. Community should create a space for intellectual openness and rigor, thus facilitating the presence of and dialogue between students, even when it is uncomfortable to do so Connections to Practice Multicultural education can do more than just present students with different perspectives and topics. When it is truly transformational, it gives students the tools with which to engage with and challenge their studies and environment. Kumashiro, K. K. (2000). Toward a theory of anti-oppressive education. Review of Educational Research, 70(1), 25-53. Summary Educators and education research has attempted to understand the dynamics of oppression and articulate ways to work against it. This has surfaced four main approaches: 1. Education For the Other - addressing oppression focuses on improving experiences of Othered students in and by mainstream society. 2. Education About the Other - focusing on what all students do know and should know about the Other 3. Education that is Critical of Privileging and Othering 4. Education that Changes Students and Society Connections to Practice Anti-oppressive education must move beyond identifying and discussing privilege and lead to transformative action prompted by a curriculum that fosters critical thinking skills to navigate systematic oppression in the real world. Kumashiro, K. K. (2001). "Posts" perspectives on anti-oppressive education in Social Studies, English, Mathematics, and Science classrooms. Educational Researcher 30(3), 3-12. Summary Adding perspectives and voices to the classroom is not sufficient to fostering anti-oppressive education; we must change what is considered the norm. Kumashiro suggests two powerful approaches to conceptualize anti-oppressive education. 1. Unknowability, multiplicity, and looking beyond the known because all knowledge is partial, multiple voices and perspectives will never disclose what is true, and stories have political effects that will alter the framework for students’ thinking and actions. Anti-oppressive education requires us to look beyond what we teach and learn. This can happen when we add experiences, contributions, and practices of Others to the social studies, math, and science, and English curricula. 2. Resistance, crisis, and resignifying the self so that students can learn new knowledge while critiquing the ways they come to know. Students need to reexamine and resist forms of repetition that hinder attempts to challenge oppression. Connections to Practice Anti-oppressive education requires that teachers not only think about core subjects, but to think about these subjects differently. In planning lessons, teachers need to leave room for the unpredictable and unknown. If we want students to understand that all knowledge is impartial, we must provide them with the skills to unlearn and to reconsider their prior knowledge as definitive truths. Leonardo, Z. (2004). The color of supremacy: Beyond the discourse of white privilege. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 36(2), 137-153 Summary The study of whiteness must critically examine both white privilege and white supremacy. White racial hegemony is secured by a process of domination that white subjects perpetrate on people of color. The conditions of white supremacy make white privilege possible. As a result, we need to look beyond the taken-for-granted privileges and look at the actions, decisions, and structures that allow Whites to be dominant and privileged. Critical analysis should begin with the objective experiences of the oppressed in order to understand the dynamics of structural power relations. Discourses on privilege can be the starting point for Whites to enter into a space for discussing race critique. Connections to Practice: Teachers need to create space for students to engage in conversations about racial domination and to confront white supremacy. We have to encourage students to think about their positions of power and privilege as they reinsert themselves into history. The first step toward solidarity between whites and non-whites begins with both a recognition and an acceptance that their privileges result from years of oppression and domination of racial minorities. McIntosh, P. (1988) White Privilege and Male Privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women’s studies, in: M. Andersen & P. H. Collins (Eds.), Race, class, and gender: An anthology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. Summary The parallel connection and intersection of different forms of oppression known as white and male privilege. Privilege is seen as a favored state (whether earned or conferred by birth or luck) yet not beneficial to whole society because it gives license to be oppressive. Regardless of a white individual’s disapproving of the systems, their change of attitude will not change the fact that privilege exists systematically. Connections to Practice In maintaining the myth of meritocracy in schools, the existence of systems of dominance is not acknowledged. Therefore white and male privileges are perpetuated in curriculum, instructional and school practices oppressing students of color and female students of color. Individuals who are privileged do not recognize these forms of interlocking oppressions because they are part of the dominant group and taught not to see it. Anti-oppressive educators must work to disrupt these systems of power through the curriculum they prepare, the resources they present (analyzing the implicit and explicit messages relayed through them) in order to develop critical thinkers that can identify, recognize and act to disrupt these systems of power. Nieto, S. (2007). Affirmation, solidarity and critique: Moving beyond tolerance in education. In Lee, E., Menkart, D., & M. Okazawa-Rey (Eds.), Beyond heroes and holidays: A practical guide to K-12 anti-racist, multicultural education and staff development (pp. 18-29). Washington D.C.: Teaching for Change. Summary Educators often think that multicultural education is moving beyond tolerance. However, Nieto reveals that tolerance is a low level of support, only following monocultural education. It should also build on acceptance, respect, affirmation, solidarity, and critique. The ultimate goal is to transcend one’s own cultural experiences through conflict and critique based on solidarity. Affirmation, Solidarity & Critique: powerful learning results from students struggling and working with one another. Student and family differences are embraced and accepted as legitimate vehicles for learning. Conflict is accepted as an inevitable part of learning. Culture is subject to critique because it is an ever evolving artifact. Connections to Practice Flexible classes based on interdisciplinary curricula and team-teaching in flexible sessions that are not constrained into a certain time limit. High expectations for all students; students with special needs taught along with others and occasionally pulled into small group instruction with other students who are not classified as having a disability.